Review Originally Published February 7th, 2001

The Spear of the Lohgin is a dark horror module for D&D developed under the D20 Trademark License by Paradigm Concepts, a newcomer to the gaming industry who plans to release further D20 adventures and a completely separate game called Pulp in the near future. The Spear of the Lohgin is the first in a trilogy which Paradigm is calling the Canceri Chronicles (which is, itself, the first installment of a trilogy, to be followed by the Milandir and Coryani Chronicles). That being said, The Spear of the Lohgin stands just fine by itself. (No, really, it does – I’m not just saying that.)

Although plagued with editorial problems and a host of execution errors, the core of The Spear of the Lohgin is an extremely evocative, fairly well-done piece of horror. It’s a bit of a fixer-upper, but worth the effort.

PLOT

Warning: From this point forward, this review will contain spoilers for The Spear of the Lohgin. Players who may end up playing in this module are encouraged to stop reading now. Proceed at your own risk.

Several hundred years ago, the Lohgin family was a noble house favored by the god Illiir, who gifted them with his own Spear, a weapon engraved with the Word of Illiir itself. The House of Lohgin fell when Jude Lohgin, enraged by his father’s favor falling upon his younger brother Vir, formed a pact with demonic forces, killed his sister-in-law, and began to open a Gate to the realms of the Triumvirate of Dark Gods. Vir, receiving word of his brother’s treachery, returned home and impaled Jude upon the Spear of the Lohgin.

Unfortunately, Vir interrupted his brother just as he opened his Gate – and something came through it uncontrolled, attempting to possess Jude. Seeing his brother torn to shreds by the demon’s rage, Vir felt his faith falter… and the Spear broke in two. Vir fled, leaving the demon trapped – pinned halfway through the Gate by the point of the holy spear. Vir would establish a new town to the south, but the demon would remain… slowly corrupting the land around him.

Centuries pass, and the PCs come on the scene. Someone has stolen the haft of the Spear of the Lohgin (which has become a holy relic), and has taken it back to the Lohgin Stronghold where the evil was done long ago. If they restore the Spear – allowing it to be removed from the demon – then the Gate will open and the land will fall beneath the forces of Dark Gods.

LOW POINTS

The most egregious flaws in The Spear of the Loghin are to be found in the boxed text: For example, I find that boxed text which summarizes an entire conversation (instead of actually letting your PCs have the conversation) is a bad idea. I think that boxed text which makes decisions for the PCs is a bad idea. I even have a sneaking suspicion that you shouldn’t have a big block of boxed text, followed by details about stuff which happens in the middle of the block.

And then there’s the text which has been boxed, which shouldn’t be boxed. And the the text which should have been boxed, but wasn’t.

If I was the suspicious sort, then I would say that this adventure was written without boxed text in mind, and then somebody came in after the fact to add the boxed text and botched the job.

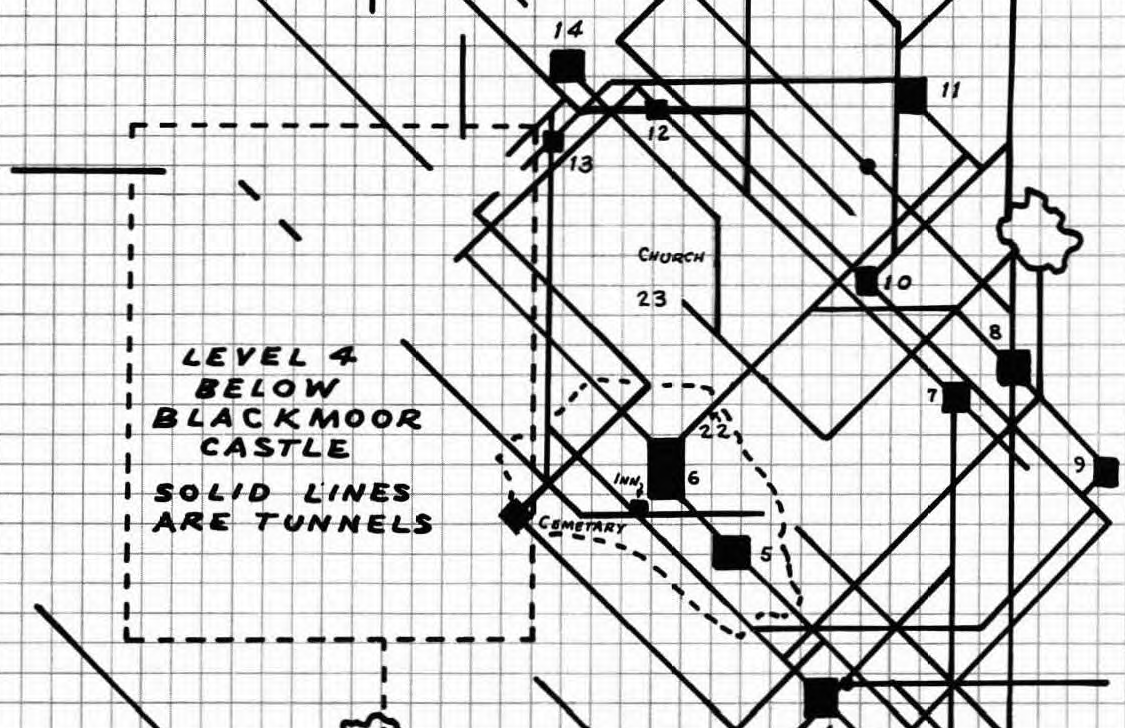

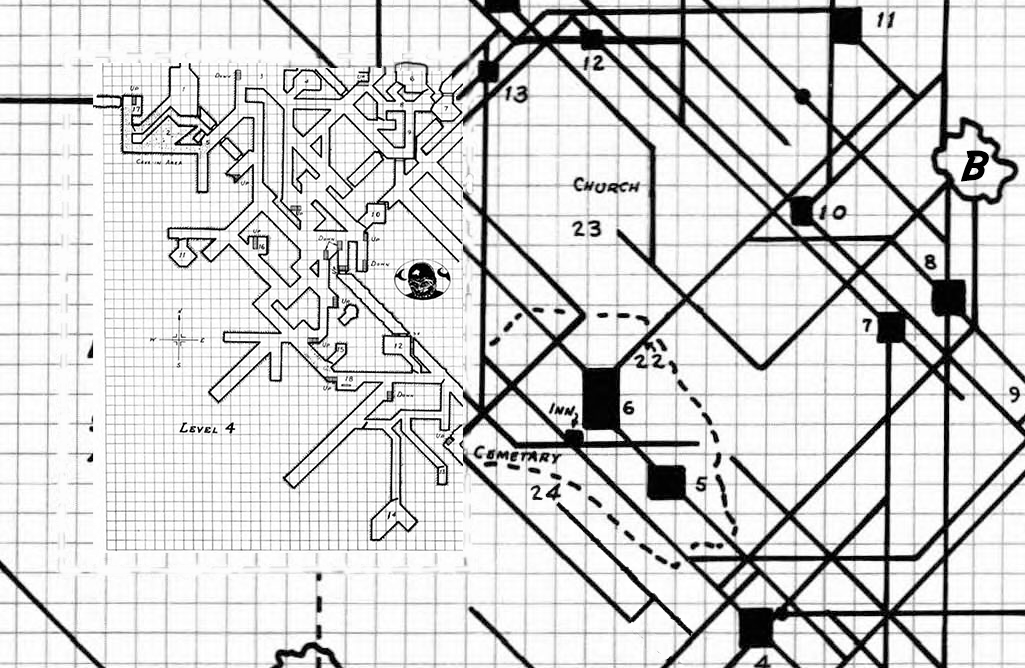

As a final, general note: As I see more and more D20 products, I’m quickly reaching the conclusion that I’m going to get very, very sick of Campaign Cartographer maps. Particularly Campaign Cartographer maps rendered in a meaningless gray scale with strange and incomprehensible symbols which are left utterly unkeyed. If you can afford a really excellent Brom cover and some average to disturbingly good interior art (as Paradigm Concepts apparently can), then find someone who can actually draw a legible map.

HIGH POINTS

I always dread reviewing products whose faults are concrete and whose strengths are ephemeral. It’s so easy to trot out a litany of flaws in such cases, pat oneself on the back, and trot off into the sunset content with the thought you’ve scored some cheap points and come across as incredibly clever.

But to do that wouldn’t be fair to products like the The Spear of the Lohgin. Yes, there are problems with the presentation. Yes, there are some questionable visual elements. Yes, there are some structural deficiencies.

But the The Spear of the Lohgin excels at putting down on the page a visceral, extremely disturbing variety of horror adventure which I haven’t seen in a published D&D product previously. It’s the type of horror which can get away with the graphic depiction of grisly detail, while – at the same time – maintaining an eerie mystery about it all. It’s a “best of both worlds” approach which I find to be extremely effective.

So, yes, there are some accessibility problems here. But I would say that it’s worth the fight to crack this nutshell – because the nut inside is of top quality.

Writer: Jarad Fennell

Publisher: Paradigm Concepts

Price: $9.99

Page Count: 32

ISBN: 1-931374-00-7

Product Code: PCI 1001

I had a weird Mandela Effect with this one. For 20+ years I’ve been convinced this module was called The Spear of Lohgin. It was even written as such in this review. When I went to grab the cover image, though, I discovered that it was, in fact, called The Spear of THE Lohgin. I have no idea how the alternate version of reality became lodged in my brain.

It’s interesting that my past-self wrote about the difficulty of expressing the ephemeral qualities of an adventure like this. Although I could not recount to you any of the specifics of the plot of The Spear of the Lohgin after all these years (and never had a chance to run it), it’s always stuck in my mind as having a very strong VIBE. Re-reading my review has encouraged me to revisit this particular module.

In fact, I’d recommend that you grab a copy, too, but that seems to be curiously difficult. Although the second module in the Canceri Chronicles, Blood Reign of Nishanpur, is still available, for some reason this one is not. Paradigm Concepts’ Arcanis setting went on to be featured in its own RPG in 2011 and featured an incredibly successful living campaign which ran for over a decade and had dozens and dozens of adventures released for it. They won ENnie Awards and Origin Awards. But their website and the Living Arcanis website went quiescent in 2020 and I was about to write that they seem to have quietly slipped away…

… except I just discovered that they’re still active on Facebook, apparently ran events at Origins and Gen Con last year, and also released a new Legends of Arcanis adventure, Things Left Behind, in August 2024. I don’t understand why the News section of their website hasn’t been updated since 2017, but good for them!

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.