AFTERMATH

A little while later, Pashar and Kora met Vajra at the front door. They briefly explained the situation.

“Is there anything else that needs to be done here?”

Pashar shook his head. “Just dead cultists. Although the woman is still alive if you need to question her.”

Pashar shook his head. “Just dead cultists. Although the woman is still alive if you need to question her.”

“What about the Cassalanter children?”

“We didn’t find them,” Kora said. “But they’re in danger. We need to find them quickly. Before the Festival of Leiruin.”

“You’ve found a solution?”

“After a fashion,” Pashar said.

“We’ll find them,” Vajra promised. “Take Jenks home. You were never here. I’ll take care of it.”

As they left, Kittisoth grabbed Renaer’s hand and gave it a little squeeze. She pulled him after her, and he willingly came.

While the others carefully guided Jenks out of the windmill (Kittisoth covered his eyes with one wing), Pashar lingered with Vajra a little longer to explain what needed to be done once the Cassalanter children were found. “Based off our research, if, when their birthday comes, the parents on whom the blood ritual is attuned and the children are dead with every trace of their original bodies destroyed, then the triggering moment of the ritual will pass. The children could then be returned to life with a true resurrection, and Asmodeus would have no further claim to their souls.”

“That’s very dark,” the Blackstaff said.

“But necessary,” Pashar said, glancing back at the room where they’d left Lady Cassalanter.

A BRIGHTER MORNING

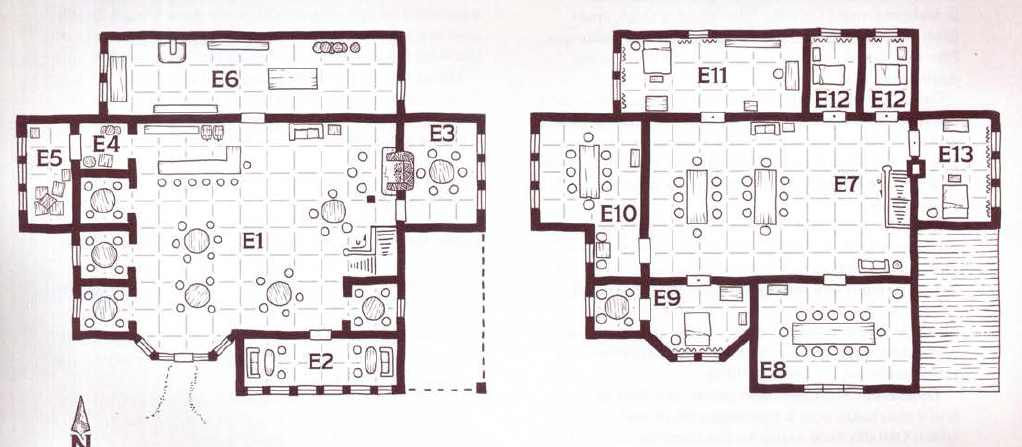

On the ride back to Trollskull, it was clear that Jenks was shattered. The horrific experiences of the last few hours had broken him. When they got back to the Manor, the other kids came rushing out of the maroon dome. There were tears and hugs and endless comforting.

The next morning, Kittisoth woke up in bed with the three kids snuggled around her. One of her wings was protectively draped over the top of them.

Renaer, who had slept in the couch in the front room, was cooking breakfast as they all came staggering out of their rooms. Kittisoth joined him and showed him how to make a pirate’s breakfast. The kids came out a little later, rubbing their eyes. Jenks was clearly still a little shaken by his ordeal, so Renaer made him pancakes in the shapes of various divine symbols and began quizzing him on which gods they belonged to.

After breakfast, Pashar and Edana headed over to Amara’s Bakery and cleaned up the blood. Kittisoth kissed Renaer goodbye and spent the rest of the morning hanging out with the kids. Kora headed to the Market to track down a dragon scale.

“How much for a gold dragon scale?” Kora asked.

“Sixteen hundred gold pieces.”

“… how much for a tin dragon scale?”

Even chromatic scales proved expensive, but they didn’t have time to wait for Zellifarn to fly back from wherever he lived (even if he’d agree to). Kora paid what needed to be paid.

Leaving Pashar to finish up at Amara’s, Edana headed over to Steam and Steel. Embric and Avi were quarreling about which one of them had won their drinking contest the night before.

“Were you drinking at Trollskull?” Edana asked.

“No,” Embric said regretfully. “We went to a friend’s party instead.”

“Oh! So you both lost!” Edana grinned. Embric and Avi laughed heartily.

“What can we do for you?”

Edana wanted two things: A mithril hammer for the vault and a set of Trollskull Manor amulets for the kids: a flask didn’t seem appropriate, but she wanted something they could theoretically cast locate object on in the future.

They could wait a few days for the amulets, but Edana agreed to give them a fistful of free drink tokens for Trollskull Manor if they finished the mithril hammer that same day. Nevertheless, with the cost of the true silver they’d completely tapped out their once substantial cash reserves.

But if everything went well, that wouldn’t be a problem soon enough.

A HARPER TRIAL

As Edana opened the front door of Trollskull Manor, however, she looked down the street and saw Dain storming down the street towards her, accompanied by a pair of men in blue robes. She sighed and went down to the bottom of the stairs to wait for him.

Dain pulled up in front of her, flanked by the other two. One was an albino elf with piercing blue eyes. The other was a dark skinned human male whose eyes were just golden spheres that glowed softly. All three of them wore their Harper pins, openly displayed.

“Where is she?” Dain demanded.

“Not today,” Edana said.

Dain opened his mouth to retort.

“Not. Today.”

“This is Harper business,” Dain said. “Move aside if you honor your oath.”

“It doesn’t have to be like this,” Edana said. “But it can’t be today.

“Are you a Harper or not?!” Dain fumed.

Edana messaged Kora. Dain’s here. He’s pissed. I’m telling him to go away. He’s not listening. Should I convince him?

Inside the Manor, Kora sighed. No. Wait for us.

A few moments later, the others stepped outside. Dain looked up at Kora, who had been the first through the door. “Kora,” he said. “I’m very disappointed.”

“I thought you would be,” Kora admitted.

“You disobeyed orders.”

“I acted with a Harper’s discretion.”

“We’ll see what the High Harper has to say about this,” Dain concluded. “You’ll come with us now. You and your friends.”

“No,” Kora said. “This was my decision. I’ll answer for it alone.”

Dain shook his head. “They’re all Harpers.”

“I’ll come with you,” Kora said. “But I can’t speak for the others.”

“You’re making this worse for yourself.”

Kora sighed. “I can’t make people do things. That’s not how the Harpers are supposed to work.”

“Couldn’t the High Harper come here?” Theren suggested. Kitti laughed from the top of the stairs.

Dain ground his teeth. “For the last time: will you come?”

The others nodded their agreement, but Kora shook her head. “Someone needs to say.” She turned to Dain. “To protect our children.” She dropped her voice to a whisper. “Please. One of them was kidnapped last night.”

Dain softened. “Yes. Of course.”

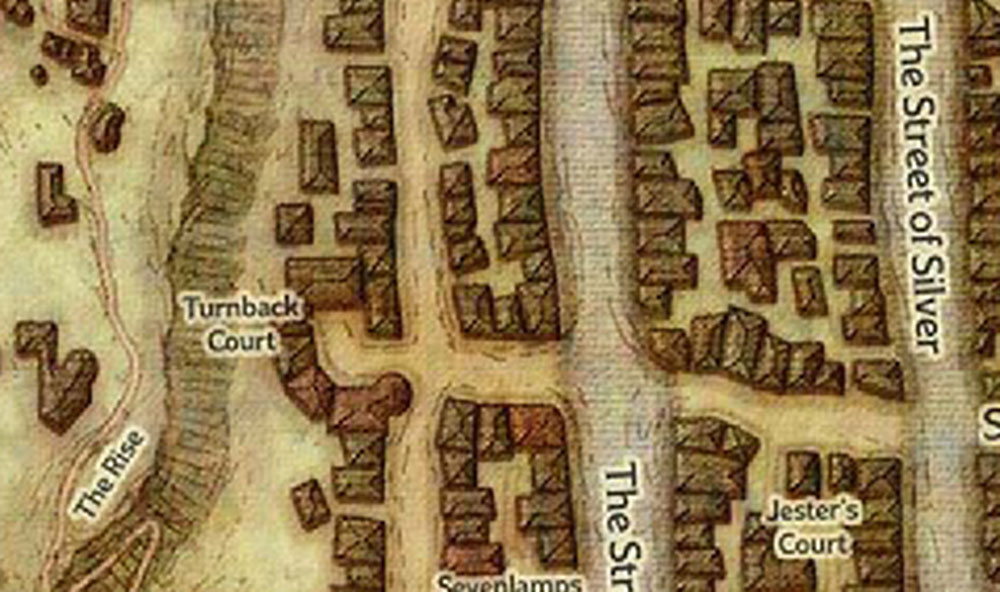

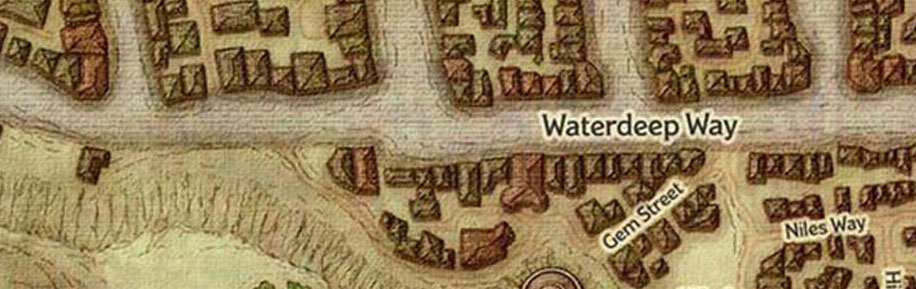

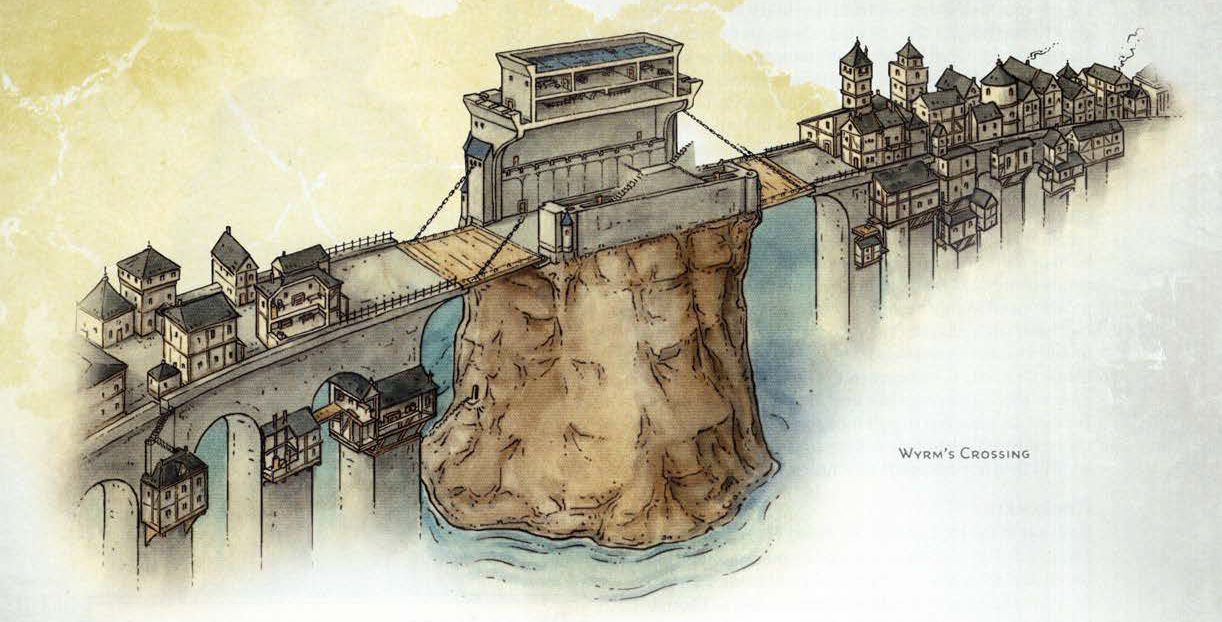

It didn’t take them long to conclude that Kittisoth — and her temper — was the best one to leave behind with the kids, and then Dain lead them across the city and deep into the Castle Ward. On Waterdeep Way, west of Castle Waterdeep and east of Piergeron’s Palace, their escorts turned abruptly and vanished into what had appeared to be nothing but a vine-covered wall a moment before. Passing through the nigh-invisible gap there, however, they found themselves climbing up the side of Mt. Waterdeep.

They climbed quite high, in fact. The griffon patrols above the city were flying even with them and the air was getting quit thin when they passed into a crevasse on the side of the mountain. There, inside a kind of cleft, they came suddenly upon a cave.

At every step along the way they had been baffled by their route. They would have never seen the gap in the wall, nor the path beyond it. There were several more turnoffs they didn’t see until they’d taken them. Even the cleft had looked like nothing remarkable until they were already on top it. It seemed as if they were in plain sight on the side of the mountain, and yet they weren’t even certain they would be able to find their way back here if their lives depended on it.

As they entered the cave and worked their way into its depths, they noticed that Dain was touching various places along the wall with clear deliberation. Whatever path he was guiding them along here was warded, and there were numerous other passages they did not take (and perhaps were not designed to be taken).

At last they emerged into the heart of a massive geode. Crystals, glittering in the light, lined the dome of the cavern and had been leveled beneath their feet to form a smooth floor. On the far side of the cavern stood a statue of a man with a bald head and long beard. Edana, Kora, and Pashar recognized this as Lord Aghairon, founder of Waterdeep. The statue was gesturing outwards, as if taking in the whole room as a conclave. In one hand it grasped an actual staff — somehow cleverly worked through a grip of stone. Pashar recognized this and gasped. Leaning over to the others he whispered, “That’s the dragonstaff of Aghairon.” The keystone of the dragonward which kept all dragons out of Waterdeep… unless they had been touched by the staff.

They realized that, as they had been captivated by the statue and staff, a dozen people had stepped forward from the darkness rimming the chamber into the light. They wore hoods low over their faces, masking their faces in shadow and leaving them unrecognizable.

Dain stepped forward. “We have brought those who are to be judged.”

A figure floated through the statue of Aghairon. The translucent blue ghost of a young elven woman, with a Harper pin fastened even upon the clothes she wore in death as a tribute to the faith which held her to this world and its business.

“High Harper,” Dain intoned, “I bring before you Harpshadow Kora and her disciples, who have confessed in writing to disobeying orders and the theft of Harper property.”

The spectral Harper spoken then. “Step aside, Harpsinger, and let them answer the charges in their own voice.” She lowered her gaze to them. “We have been told that you have disobeyed the orders of a Harper given to you in good faith, and that you have betrayed the Harper trust by aiding and abetting our ancient foes the Zhents. You have furthermore stolen a cache of Harper supplies which are to be used in the struggle against all evil and injustice in the world. How answer you?”

Kora took a step forward. “First and foremost, we have stolen nothing. We have secured the cache, intending to keep it safe until it could be relocated. This we have done. Nothing has been despoiled. Nothing has been taken.”

“Where is the cache now?”

Theren spoke up. “I have it here in this bag of holding. I can dump it out here if you would like.”

“Unnecessary,” the High Harper said. “And where did you plan to relocate the cache?”

“The city recently bestowed the abandoned property of Thunderstaff Villa to us, beneath which there are hidden chambers which can be easily secured,” Kora said. “We intended to consult with Dain before placing the cache there, but we think it would make a good location.”

“And how do you answer the charge of being complicit in the plots of the Zhents?”

“We killed Manshoon!” Kora said indignantly. “And, yes, in this effort we allied with the Doom Raiders, who are also of the Zhentarim. In working with them, however, we have learned that they are not evil actors. They seek to shake off the malignancy of Manshoon. Are the Zhents truly the enemies of the Harpers? Or was Manshoon enemy to us both?”

Dain harrumphed from his place off to one side.

“You are young,” the High Harper said. “We have often seen the Zhents mislead those who are young.”

“Perhaps,” Kora said. “But if we have been ‘misled’ in to slaying Manshoon, will this council object?”

Edana stepped forward. “Shedding blood merely because they are living in a specific building seems unnecessary. And unjust.”

Theren agreed. “They have legal ownership of the tower. If we had done what we were ordered to do, we would have been in the wrong.”

“And we are not mere thugs to be ordered about!” Kora declared. “We are thinking people! We are a powerful group! We have brought demon-worshipping nobles to heel and thwarted Jarlaxle! We have infiltrated Xanathar’s lair! We have killed Manshoon!”

“We are no children to be summoned for scolding,” Edana said.

“We are Harpers,” Pashar said. “We are meant to be just and lenient! We are meant to use not only our initiative, but our judgment! And Dain has shown no judgment at all! Not only were these orders ill thought, but he had previously ignored us when we told him that one of his superiors had been enthralled by Manshoon!”

The spectral Harper seemed taken aback. “What is this?”

Dain snorted. “It’s a ridiculous conspiracy theory! They accused Mirt of being a traitor, but I think the truth of it is that they are the traitors!”

“We told you that Mirt had been compromised and that he needed help!” Theren shouted.

“Help that the Blackstaff is now providing,” Kora stated simply, laying a calming hand on Theren’s shoulder.

“The Blackstaff?”

“Dain wouldn’t do anything,” Theren said. “So we went to Vajra.”

“Surely someone here other than we are close to the Blackstaff and can verify the truth?” Kora asked.

A murmur passed around the chamber.

Edana spoke up. “The point is that you recruited Kora and promoted Kora because she is wise and kind and just. I became a Harper because of her. And if you don’t trust her judgment, then I have been misled about what it means to be a Harper. She is the best of you!”

The High Harper floated back a few paces. At some unspoken signal, two of the gathered Harpers stepped forward. The rest stepped back. The broken circle looked around at each other, there were nods, and then the two who had stepped forward also stepped back, as if to form a concensus.

“I see,” the High Harper said, coming forward again. “You have been found… innocent. And justified in your actions. Here is my judgment upon you: Brightcandle Kora, you will be taking over responsibility for the North Ward.” (“Oh shit,” Kora murmured.) “You will begin your work with your fellow Harpshadows. You have much work to do and we trust your judgement.” She turned to Dain. “Dain, we understand your concerns. But perhaps it will be best if Brightcandle Kora is allowed the… how did you put it, Pashar? The… initiative to follow her own instincts, in the Harper fashion.”

Kora bowed her head, uncertain of what she truly thought or felt, but certain in this: “You will not regret this.”

One of the Harper lords stepped forward from the circle and lowered his hood. It was… Mattrim Three-Strings, the bard from their own tavern. He winked and led them out of the cavern and back to the wall onto Waterdeep Way. “We’ll talk later,” he said, and then vanished in to the crowds.

KISS AND TELL

“Mattrim Three-Strings?!” Kitti shouted. “That’s amazing!”

They had just finished telling her the tale of their trial. Kora still seemed a little shellshocked. Kittisoth pushed a glass of whiskey over to her.

“For an organization founded to undermine authority…” Pashar mused.

“…they get real twitchy whenever somebody questions theirs,” Edana finished his thought.

“I’m just glad they came to the right decision, otherwise–“

There was a knock on the door.

“Ah, fuck,” Kittisoth said and opened the door.

Amara was standing there.

“Oh my god! Come in!” Kitti gestured with her hand, throwing her wings back to open the way.

Amara was clearly a little shaky. There were tears in her eyes. “The Blackstaff told me what you did for me. I can’t thank you enough!”

“Come in! Come in!” Kitti demanded. “And we should be thanking you! Or apologizing! We had no idea that we were putting you in danger.” She led Amara over to the couch and pushed a glass of the whiskey into her hands.

“Thank you,” Amara said again. “The Blackstaff — I still can’t believe that was the Blackstaff! — told me a lot of what happened. I just wanted to come by and say… I’m all right. Yes. I’m all right.”

Jenks, having heard her voice, came running into the room and gave her a big hug. “Amara! Oh, Amara! I thought your were dead!”

“I was,” Amara smiled. “For a little while. It’s all right Jenks.”

Jenks stepped back and wiped a tear form his cheek.

Amara patted him on the shoulder. “I’ll understand if you don’t want to come back to the bakery—”

“No!” Jenks cried. “We’ve got to bake the bread! We need to break the crust!”

Amara grinned. “That’s right, Jenks. You’ve got to break the crust!”

They hugged again. A little while later, Amara said her goodbyes. Kittisoth waved goodbye as she headed down the street and then shut the door. She turned back to look at the rest of the group. Everyone sighed heavily. It had been a long day and—

There was a knock on the door.

“Gods dammit!” Kittisoth exclaimed.

She opened the door. It was Embric, delivering the mithril hammer. “I’ll see you tonight for those drink tokens!” he laughed, heading back down the stairs.

Kittisoth shut the door again. “So who do we leave in charge of the kids while we head back to the City of the Dead?”

“Hasn’t Renaer been hanging out all afternoon?” Edana suggested.

Renaer — who had, in fact, already been playing with their kids in their room — was more than happy to oblige. He leaned in and give Kitti a deep kiss. The others cheered.

“Stop it!” Kittisoth glared at them. Then, with a grin, she went back in for a second helping, raising her wings to afford a little privacy.

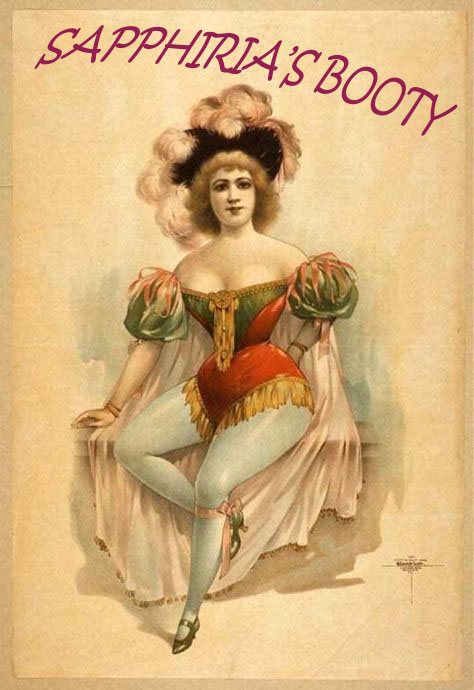

Arriving at the theater, they found it under guard. Suspicious looking thugs were watching the front door from across the street, and a couple more were loitering around the side entrance. The thugs looked human, but… They shrugged and headed down the alley, passing by posters still advertising performances of Sapphiria’s Booty and identifying themselves to the thugs. “We’re here to meet with Rongquan. Is he in?”

Arriving at the theater, they found it under guard. Suspicious looking thugs were watching the front door from across the street, and a couple more were loitering around the side entrance. The thugs looked human, but… They shrugged and headed down the alley, passing by posters still advertising performances of Sapphiria’s Booty and identifying themselves to the thugs. “We’re here to meet with Rongquan. Is he in?”