Descent Into Avernus begins by having the PCs stand around doing nothing while the GM describes an NPC doing awesome stuff. It then proceeds almost directly to, “If the players don’t do what you tell them to do, the NPCs automatically find them and kill them.”

It’s not an auspicious beginning.

THE PREMISE

Let’s back up for a second and briefly sum up the essential back story:

- 140+ years ago, an angel named Zariel convinced the holy knights of the city-state of Elturel to ride with her on a glorious charge into Hell itself.

- This went poorly: Many knights deserted the campaign, fled home, and shut the gate behind them. The rest of Zariel’s army was wiped out, Zariel herself was captured.

- After her capture, Zariel was tempted to evil. Swearing fealty to Asmodeus, she became the Archdevil of Avernus. Still filled with hatred for the knights who had betrayed her, she watched Elturel from afar and waited for an opportunity to present itself for revenge.

- Meanwhile, the knights who had fled back to Elturel lied about the glorious battle they had fought on the other side and their order became known as the Hellriders.

- Many decades later, Elturel was plagued by a new evil: The High Observer of the city was secretly a vampire lord. In this, their darkest hour, the god Amaunator responded to their holy prayers and the Companion appeared in the skies above the city: A second sun that burned through the night and whose light no undead could endure.

- Except this was a lie: The Companion had actually been crafted by Zariel, who had cut a deal with someone in Elturel (more on this later). Under the light of the Companion, the city of Elturel was bound to an infernal pact. After fifty years, the city and the souls of all its inhabitants would belong to Zariel.

- A few days ago, that happened: The entire city of Elturel was pulled into Avernus, the first layer of Hell.

- Among those lost in Elturel was Grand Duke Ravengard, ruler of Baldur’s Gate, who had been visiting the city on a diplomatic mission.

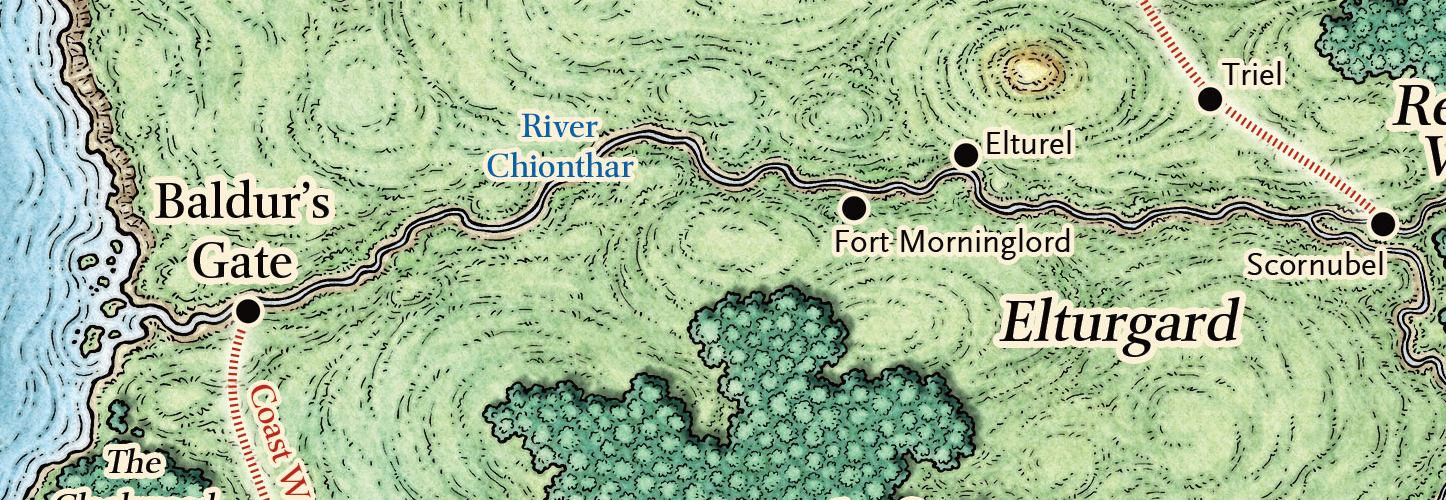

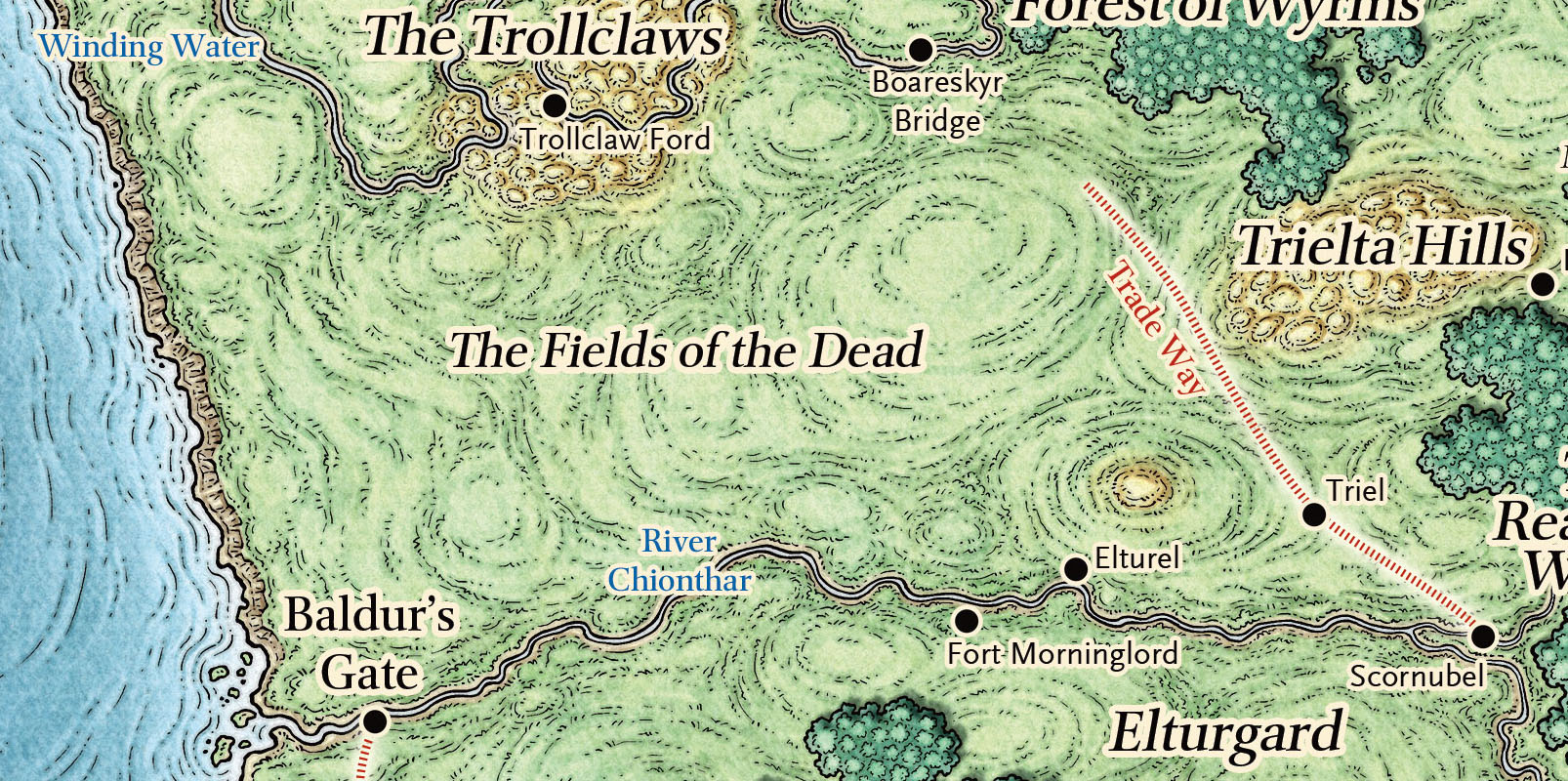

- Refugees fleeing the catastrophe head down the River Chionthar to Baldur’s Gate. The city is overwhelmed and orders the gates closed.

Descent Into Avernus opens with a blob of boxed text that informs the players that, due to the crisis, they have been drafted into the Flaming Fist, the mercenary guard who has served as Baldur’s Gate’s military and police force for hundreds of years, and ordered to report to Flame Zodge at the Basilisk Gate.

(The adventure actually refers to him as “Captain Zodge,” but there are no captains in the Flaming Fists. Their ranks are: Fist, Gauntlet, Manip, Flame, Blaze, and Marshal. Later on a “Commander Portyr” similarly shows up who should actually be either Blaze Portyr or Marshal Portyr.)

The PCs show up at Basilisk Gate just in time to stand around while the GM describes Flame Zodge jumping into the middle of a riot, kicking ass, and being awesome. Once the cut scene wraps up, Zodge comes over to the PCs and tells them that cultists worshipping the Dead Three (Bane, Bhaal, and Myrkul) have been taking advantage of the current crisis to go on a murder spree. They need to go meet with an informant named Tarina at the Elfsong Tavern.

If the PCs refuse to do it, he has them “executed on the spot.”

If they accept the gig, but then don’t follow through, he sends a squad of soldiers to track them down and “kill anyone who refuses to go.”

If the PCs escape, Zodge sends two more squads to murder them.

REMIXING

The “do what I say or I’ll arbitrarily kill your characters” motif is problematic for what I’m hoping are fairly obvious reasons. The fact that Descent repeats it three times in rapid succession here, however, mostly serves to point a big, flashing arrow at the more significant problem:

Neither the players nor their characters are given any reason to care about what’s happening.

What you have here, basically, is a broken scenario hook that the designers have so little confidence in that they feel the need to hold a gun to the players’ heads.

So how do we fix it?

As I wrote in my design notes for scenario hooks in Over the Edge, a scenario hook should be specific: What is the specific thing that gets the PCs involved in the current situation?

“You’ve been drafted by the Flaming Fist” is specific, but its first failure is our next requirement: The players should experience the hook. By having the PCs get drafted off-screen before play even begins, Descent distances the players from the hook. Not only will this make them care less about the hook, it will also make the hook less memorable. This should be particularly avoided with the hook for an entire campaign, because you don’t want the players to get three or four sessions into things and completely forget why any of this is happening in the first place.

Ideally, the PCs (and players) should also be motivated by the hook. And it’s better if this motivation aligns with what you want them to do. (This is less critical if you design situations instead of plots because then you don’t actually care what the PCs actually do; you just want to expose them to the situation so that they can begin interacting with it.)

Being press-ganged and threatened with death can certainly motivate you, but what it’s primarily motivating you to do is get out of that situation. That’s why Descent is obsessed with tracking down PCs who bail out on the job: On some level it recognizes that it hasn’t motivated the PCs to investigate the murders; it’s only motivated them to escape the Flaming Fists.

(Designing the scenario hook so that it motivates the PCs in multiple ways is also pure gold if you can pull it off. Or, alternatively, simply align multiple hooks to all point in the same direction.)

Finally, the best scenario hooks won’t be transitory or disconnected from what happens next. Instead, they will continue to resonate — thematically, structurally, meaningfully — not only with the adventure, but with the campaign as a whole.

None of these are hard-and-fast rules. But they’re useful rules of thumb.

Now, I don’t want to completely toss out Flame Zodge or the mission he gives to the PCs. (That would require a much more thorough transformation of the first act of the campaign.) But what we will do is restructure the opening beats of the campaign to get a hook that will drive us all the way to the Gates of Hell.

REFUGEES

The central pillar of Descent Into Avernus is the city of Elturel: What happened to it? Why did it happen? How can it be saved?

Everything revolves around this city… or, at least, it should. In practice, it is curiously absent from the campaign, particularly during the first act. The PCs need to care about what happens to Elturel, but they’re never given a reason to do so.

The easy solution here, of course, it to simply have the players create characters from Elturel or with strong connections to Elturel. That’s fine, but you again run into that off-camera problem: You’ve told the players that their characters care about Elturel, but you haven’t actually shown that. You need to actually bring that connection to the table and let the players experience it.

Our method for doing this is obvious: The refugees.

Instead of starting the adventure with Flame Zodge, we’ll start with the PCs guarding a caravan of refugees trying to reach Baldur’s Gate. Broadly speaking, there are four ways to do this:

- IN MEDIA RES: We open the campaign with the PCs already journeying along the road with the refugees heading towards Baldur’s Gate.

- REFUGEES ON THE ROAD: The PCs are riding along the River Chionthar when they begin encountering refugees coming from Elturel. One group of refugees is put in danger (an attack by bandits perhaps), and the PCs have to respond to it. The refugees then ask them to guard them the rest of the way to Baldur’s Gate, “where we are sure to find safety and refuge.”

- NEAR MISS: The PCs are journeying to Elturel. At the top of one hill they see the gleaming city ahead of them. They go down into a valley, there’s a cataclysmic clap of thunder, and when they reach the top of the next hill they see that the city has vanished! They are right there at ground zero as the crisis begins.

- PRELUDE TO DISASTER: The PCs are actually in Elturel when something goes horribly wrong with the Companion in the sky above. Black lightning seems to be attacking the guardian of the city! Then black lightning begins lancing down, as well, striking buildings, streets, and people. Panic sets in and some people begin trying to flee the city. The PCs barely escape when the city suddenly vanishes!

Generally speaking, the further down the list you move the more immediate and visceral the crisis becomes, but it also becomes more difficult to ensure that the PCs end up heading towards Baldur’s Gate. Having them actually in the city sounds amazing, but there’s a risk that they won’t take the cue to get the hell out of Dodge (pun intended)!

Option: Start with the “In Media Res” option, but then flashback to earlier scenes so that the players can actually roleplay through the crisis, triaging survivors, organizing the caravan, etc. You can alternate these flashback scenes with various Crisis on the Road scenes.

Option: Instead of just opening with “Near Miss”, launch the campaign as if it’s a perfectly normal campaign based out of the city of Elturel. Send the players out of the city on a typical 1st level quest. Something simple like a 5 Room Dungeon. (Maybe this dungeon could actually include some subtle clue or foreshadowing of the Cult of Zariel, see Part 3 of the Remix.) As they ride back towards Elturel—BAM! Cliffhanger. End of session.

PREPPING THE CARAVAN

You’re going to prep and run the refugee caravan as if it were a party. (See the Party Planning game structure for more details.) This might seem weird at first glance, but structurally it makes a lot of sense.

REFUGEES: At a minimum you’re going to want to prep 4-6 refugees. I’d actually recommend 10-15. Use the Universal Roleplaying Template to make these characters really come alive. It may make sense to start with a smaller caravan that slowly gathers more people as time passes. In either case, there are likely more refugees than just the ones you’ve prepped, but the ones you’ve prepped will be the “face” of the crisis that the PCs interact with the most.

MAIN EVENT SEQUENCE: Many of your events will be crises that the PCs have to face along the road, but they can also include landmarks, encounters with other refugees, etc. A few thoughts along these lines:

- Bandits attack.

- They find the corpses of other refugees who were ambushed.

- Alyssa, one of the refugees traveling with them, is pregnant and goes into labor.

- The axle of one of the wagons breaks.

- They pass Fort Morninglord. It remains a cursed place that even refugees shun instead of using for refuge. The nearby temporary fort of the Order of the Companion has been overwhelmed by refugees.

- Mischievous fairies are stealing their food.

- They pass a campground where a large number of refugees are gathering.

- They encounter a ship sailing up or down the River Chionthar.

- A large number of ships come sailing up the River; word has reached Baldur’s Gate and an impromptu alliance of fishermen has gathered supplies and is sailing up river to see what they can do.

- A group of Hellriders goes galloping past (either towards or away from the city).

- Cult of Zariel members attack the refugees. (They might have actually been traveling with them as refugees.)

- A platoon of Flaming Fist is marching towards Elturel. They are stopping refugees and roughly questioning them, attempting to ascertain the fate of Grand Duke Ravengard.

Include the need for food and water here. I wouldn’t recommend a full simulation: Just include a few events where food or water is running short and the PCs need to figure out how to solve the problem.

As you’re creating your refugee NPCs, you’ll also discover interpersonal conflicts that can be seeded into the main event sequence.

The distance from Elturel to Baldur’s Gate is nearly 200 miles. Given the pace at which the refugees are likely to be traveling, it’ll probably take ten days for them to reach Baldur’s Gate. Don’t feel like you need to pack in a lot of events every day. Two or three is more than enough to set the tone, and many of those can be very brief. Once the PCs manage to establish a routine, it might also feel right to sum up a couple days of travel in a short bit of narration before zooming back in for the next crisis.

RUNNING THE CARAVAN: When running a party, there’s a persistence of action as you’re generally playing things out in Now Time. For the caravan, things are going to be more abstract; you’re going to be using eliding narration and doing sharp cuts between interesting moments. Make sure to both give time and frame scenes for the PCs to interact with the NPCs. The mental checklist for running a party remains useful:

- Which NPCs are talking to each other? (Consult your refugee list.)

- Who might come over and join a conversation the PCs are having? (Again, refugee list.)

- What are they talking about?

You might find it useful to habitually frame an “evening camp” scene each day – a sort of “mini-party” where you can pack in a bunch of different social interactions. Other opportunities include:

- While traveling the road.

- While relieving yourselves on the side of the road.

- While sharing a night’s watch.

- While sharing a meal or filling waterskins in the river.

If the players are enjoying themselves, let them feel the full ten days of the journey. If they don’t seem to be getting into it, make sharper cuts and move the clock forward, but still try to make sure they get a chance to really interact with the refugees.

Design Note: At some point, I recommend having one of the refugees mention that Elturel has never faced hardship like this; not even during the Night of the Red Coup and the rule of the Vampire Lord Ikaia (see Part 4B).

AT THE GATE

When the refugee caravan arrives at Baldur’s Gate, they find the situation as described at the beginning of Descent: The gates have been shut. A huge refugee  camp is growing outside the walls, but it’s clear that supplies are short out here. If they want to keep their refugees safe, they’ll need to figure out how to get them inside the city. (If nothing else, from there they could arrange passage on a ship sailing to safer ports.)

camp is growing outside the walls, but it’s clear that supplies are short out here. If they want to keep their refugees safe, they’ll need to figure out how to get them inside the city. (If nothing else, from there they could arrange passage on a ship sailing to safer ports.)

If they approach the gates directly, they meet Flame Zodge. Otherwise, someone will point them in Zodge’s direction as the “guy who can solve your problems if you can make it worth his while.” Alternatively, Zodge hears rumors about how the PCs kept their caravan safe on the road and comes out into the refugee camp to find them.

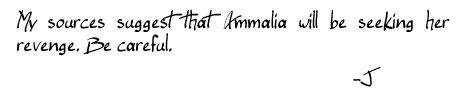

ZODGE’S DEAL: Basically, Zodge sizes them up, concludes they might be useful, and offers them a deal. If they agree to be deputized as members of the Flaming Fists and investigate the killings, he’ll let their refugee caravan into the city.

This is important: Deal-making is another central theme of the campaign.

The deal Zodge is offering isn’t literally a diabolical one (it’s actually quite reasonable and there’s no hidden loophole waiting to stab the PCs in the back), but it’s a minor echo of the infernal pacts that are coming later. So don’t just shake hands on this: Have him actually produce enlistment papers and make sure the PCs sign them.

Option: Produce the enlistment papers as actual props and have the players sign them at the table. Once they’ve done so, whisk them away and make a point of tucking them away somewhere safe where they can’t get to them.

The enlistment contract contains a reddish sigil in the form of a watermark. Once the papers are signed, Zodge will produce a symbolon knife and make an irregular cut through this watermark, giving the half he slices out to the PCs along with their badges. (The irregular edge of the watermark can only be uniquely matched to that specific contract, allowing all signers to verify the agreement. This interaction foreshadows the contract sealed between Zariel and Elturel, as described in Part 4 of the Remix.)

In addition, as we’ll discuss in more detail in Part 3 of the Remix, the killings are specifically targeting refugees. Here, again, we are tying the details of the scenario hook to the wider themes of the campaign.

LEVEL UP: Once the PCs have signed their enlistment papers, they can advance to 2nd level.

One of the problematic elements in Descent Into Avernus is the pace and timing of the PCs leveling up. For example, the PCs are supposed to level up after the first SCENE of the adventure. (So you create your characters and then maybe 20 minutes later you pause the narrative so that they can level up.)

We’ll probably do a more in-depth discussion of this issue in Part 8 of the Remix as we’re wrapping things up, but we’ll get started by cleaning it up here.

(If you don’t want to run the full-fledged refugee caravan adventure described above, then I recommend just having the players create 2nd level characters straight out of the gate.)

THE MYSTERY OF ELTUREL’S FATE

The last element we want to strongly establish for the campaign here is the mystery of Elturel’s fate. This can actually be broken down into three separate revelations:

- What happened to Elturel? (It was taken to Hell.)

- Why did this happen? (The city was sold as part of an infernal pact.)

- The true history of the Hellriders. (They betrayed Zariel and left her for dead in Avernus.)

In my opinion, the PCs should NOT know (or even suspect) any of these answers when the campaign begins. (If you’re using the “Near Miss” or “Prelude to Disaster” openings, you’ll want to give careful consideration to exactly what the PCs actually witness when Elturel vanishes.)

In Getting the Players to Care, I discuss a number of ways in which GMs can get their players to actually care about the lore of the world. These include:

- #2: Make It Plot

- #4: Make It Mystery

- #5: Make It Personal

- #7: Make It Repetitive

And we’re going to use all of these to make them care about Elturel’s fate.

RUMORS OF ELTUREL: We’re going to create a sense of enigma around Elturel’s fate primarily by making it the #1 topic of conversation. Virtually everyone the PCs talk to has a different theory or has heard a different version of what happened to Elturel. (And what’s going to happen next? Are more cities going to be destroyed? Is Baldur’s Gate in danger? Did you hear that Waterdeep has been destroyed, too?) You can find twelve fully developed rumors of Elturel’s fate in the Rumors of Elturel addendum to the Remix.

Seed these rumors into:

- Conversations with the refugees, and with others met along the road to Baldur’s Gate.

- People desperately asking for fresh news as the PCs arrive in the refugee camp outside the city.

- Flame Zodge’s briefing.

- Town criers shouting out the latest headlines on the street corners of Baldur’s Gate.

- Conversations at the Elfsong and Low Lantern taverns.

And don’t just have the NPCs deliver these rumors. Flip it around and get the players involved by having NPCs ask the PCs what they think happened. (This will force the players to actively engage with the rumors and really think about them.)

ESTABLISHING THAVIUS KREEG: Among the rumors and other discussions, make sure to repeatedly establish that Thavius Kreeg was (a) the High Observer of Elturel and (b) he’s missing and presumed lost with the city. (We’ll discuss this more in Part 3, but you want to firmly establish these facts so that the players will understand the significance of finding Kreeg alive later.)

THE SOLUTIONS: The PCs will be able to gather clues to the first two revelations (What happened to Elturel? and Why did this happen?) throughout Part 3: The Vanthampur Investigations before getting definitive answers in Part 4: Candlekeep.

The true history of the Hellriders can be discovered in Part 5: Hellturel and Part 6: Quest of the Dream Machine. (This is deliberate: We want them to learn and fully care about the official history as it’s been known for hundreds of years before revealing the truth. You can’t yank the rug out from under them if you don’t let them walk onto the rug first!)

We’ll discuss these mysteries in more detail (and probably look at complete revelation lists) as they come up.