Go to Table of Contents

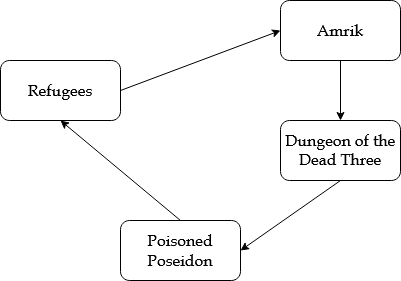

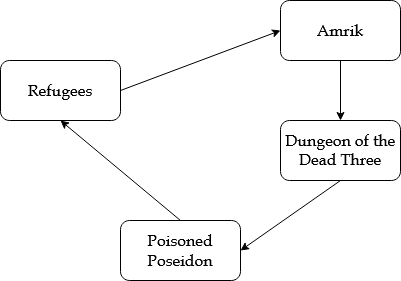

As we discussed in Part 3, the Vanthampur Investigations consist of three nodes:

- Dungeon of the Dead Three

- Amrik Vanthampur @ the Low Lantern

- Vanthampur Manor

To these we’re going to add a fourth node:

The Poisoned Poseidon is a beached ship that’s been repurposed into a tannery. It’s also the location where the Dead Three cultists are killing refugees before dumping their bodies. There are a couple of reasons why we’re adding this node to the scenario:

First, as we’ll see in “Portyr Politics” below, I wanted to enhance this section of the campaign by giving the PCs a window into the evolving political situation in Baldur’s Gate (and how that ties into both the refugees they care about and Vanthampur’s schemes). The most effective structure for that material required an extra “beat” before the Dungeon of the Dead Three, which means that we need an extra node.

Second, extensive feedback from DMs online suggests that the Dungeon of the Dead Three is a better experience for 3rd level PCs than for 2nd level PCs. Adding an extra node here also provides a natural opportunity for a milestone. In Act I of the campaign, the PCs should level up after:

- Reaching Baldur’s Gate

- Poisoned Poseidon OR Amrik Vanthampur (whichever they do first)

- Dungeon of the Dead Three

- Vanthampur Estate

Meaning they’ll be 5th level when they head to Candlekeep (and, subsequently, Avernus).

REMIXING THE CONSPIRACY

There’s a million and one ways to create a thing, but generally the first thing I do when designing an adventure or campaign is to simply brainstorm ideas. (I describe a quick version of this in 5 Node Mystery.) We’re remixing the raw material from Descent Into Avernus here, so we can largely skip that step.

When it comes to the actual design work — when I start thinking about how a particular scenario is going to work in play — however, the first thing I’ll do is focus on how the scenario works in the game world. Once I know that, I can start figuring out what sort of scenario structures to use, how the PCs can get hooked into the scenario, and so forth. (Along the way, I’ll almost certainly tweak how the game world is arranged in order to facilitate the table experience, but balancing these factors of simulation, challenge, drama, practicality, scope, etc. — and which ones are more important or more valued — is (a) a matter of personal taste, (b) dependent on circumstance, and (c) a bag of worms I’m not going to dive into today.)

Long story short, in the Remix, this is how the Vanthampur conspiracy to kill descendants of Hellriders and knights of the Order of the Companion works in the game world:

- Amrik Vanthampur has set himself up as a black market resource for smuggling refugees into Baldur’s Gate. His agents circulate through the refugee camps outside of the city and he holds court at the Low Lantern, fleecing refugees who want to bring their loved ones inside the city. (This will be described in Part 3H.)

- This puts Amrik in a position to identify and track refugees of the desired bloodlines.

- Duke Vanthampur, with the aid of Thavius Kreeg and Gargauth, has cut a deal with the Dead Three Cultists to actually carry out the murders. (See Part 3B.)

- The operation is overseen by Mortlock and the Dead Three cult leaders at the Dungeon of the Dead Three. Once Amrik has identified a target, he sends word to Mortlock, who instructs the Dead Three cultists to put the target under surveillance. (See Part 3F.)

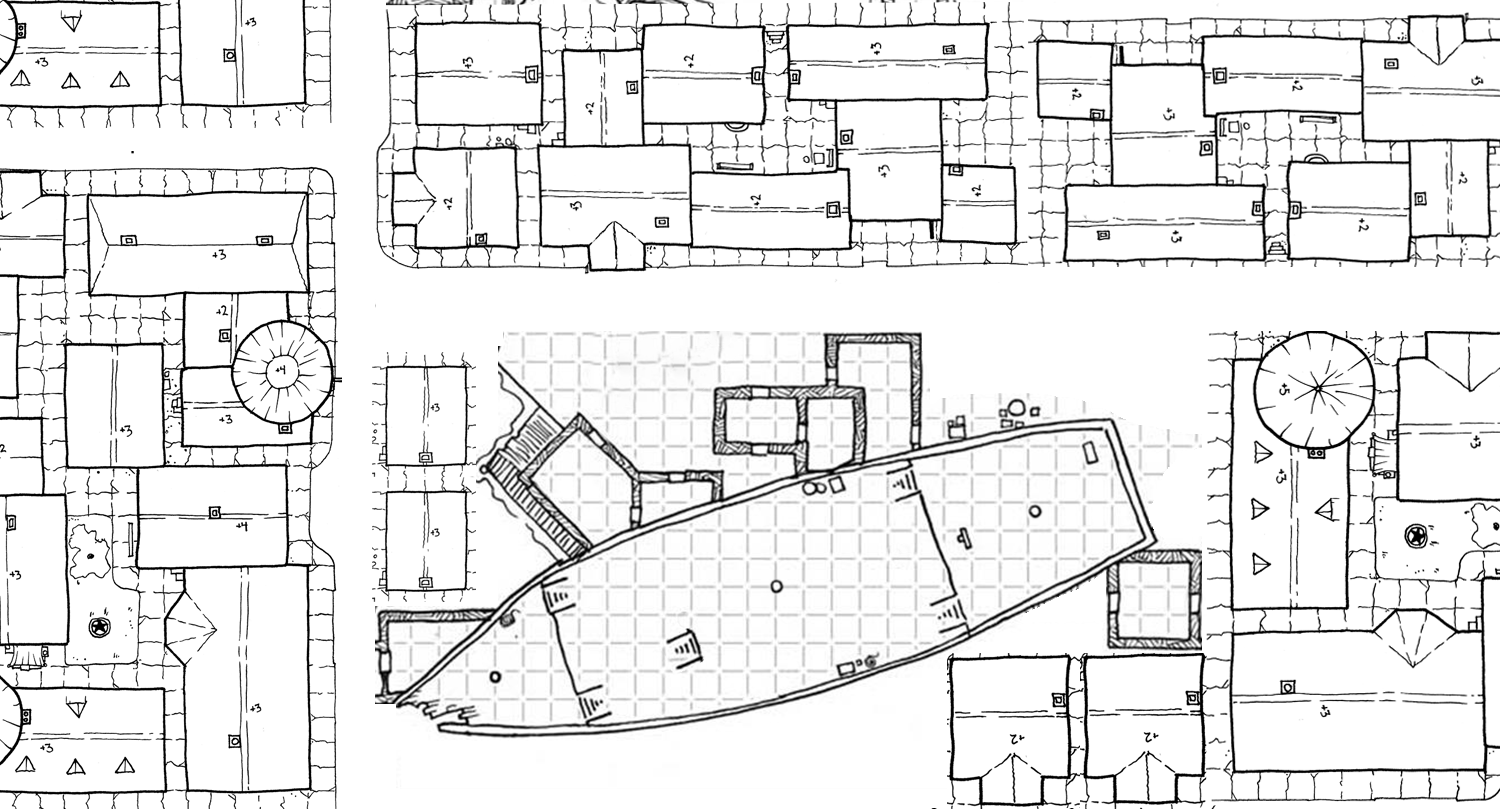

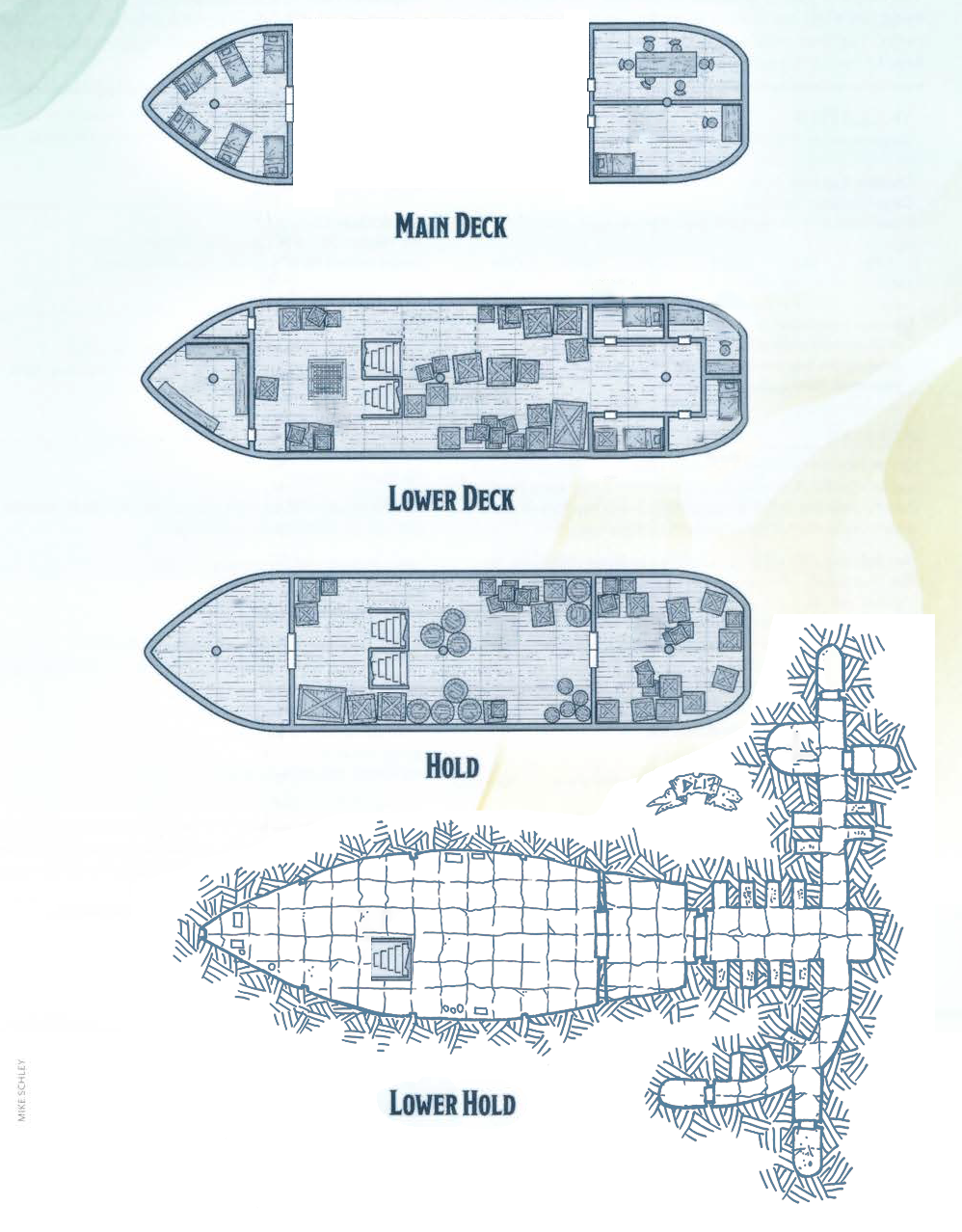

- The actual murders are carried out by Dead Three cultists operating out of the Poisoned Poseidon. Once a target’s location and identity have been confirmed, the surveillance teams will report that information to the Poisoned Poseidon. (See Part 3E.)

- A Poseidon strike team will then kidnap the victim, bring them back to the slaughterhouse, kill them, and dump the body in Insight Park. (See Part 3D.)

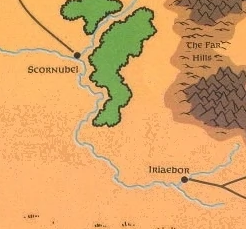

At this point, we could put together a little diagram of how the scenario works:

Refugees go to Amrik for help, Amrik gives their information to the Dungeon of the Dead Three, who passes the target information to the Poisoned Poseidon, who kill the targeted refugees.

(You don’t necessarily need to actually draw this out on a sheet of paper, but you may find visualizing it useful.)

Note that this has nothing to do with the PCs or their involvement in the scenario. I’m not focused on that at all right now. All of my attention is on figuring out the practical details of the situation in the game world.

The nature of these practical details can also vary a lot. In situations like this where the bad guys are in the middle of an ongoing project, though, the result will usually be some sort of logistical map for information, money, people, etc. This usually lends itself naturally to node-based scenario design.

Option: On p. 197 of Descent Into Avernus, there’s a group of Dead Three cultists based out of the Hamhocks Slaughterhouse who are ALSO murdering people across the city for vague and unspecified reasons and then dumping their bodies at the Smilin’ Boar tavern. I’d originally planned to just scoop them up and add them to the Vanthampur conspiracy, but realized I couldn’t quite make it work: The Slaughterhouse is outside the city because no hooved animals are allowed inside the walls, and it doesn’t make sense for the Dead Three to smuggle refugees OUT of the city, murder them, and then smuggle them back INTO the city to dump the bodies.

However, if you wanted to add more complexity to this section of the campaign you could still scoop up this material. Now there would effectively be two Dead Three operations hunting refugees: One inside the city walls and one outside the city walls. (Both operations are probably still linked to Amrik.)

(I even had a cool clue for the Hamhocks Slaughterhouse that I didn’t get to use: Blue blood on one of the victim’s clothes. In Baldur’s Gate, only the Hamhocks Slaughterhouse practices the slaughter of giant spiders.)

HOOKS

Once we understand the scenario, we can start looking at how the PCs can get involved. Because we’re not prepping a plot, we could theoretically generate lots and lots of scenario hooks, pointing them at any or all of the nodes we’ve designed. In practice, however, this is the point where we’ll usually start thinking about the scenario structurally in terms of how the PCs interact with it, which in the case of a conspiracy usually translates into a hook pointing somewhere at the periphery of the conspiracy (so that the PCs can learn more and more about the conspiracy as they work their way towards its center).

In this case, our little flowchart is a perfect loop: What’s the periphery? Well, we know that the Dungeon of the Dead Three is the control hub for the conspiracy. And, structurally, it will also be where the major leads to the next section of the campaign (Vanthampur Manor) will be found. Therefore, we can look at the point furthest from the Dungeon of the Dead Three: The refugees.

Once we’ve made that determination, a clear structure kind of leaps out at me: From the murdered refugees, the PCs can work their way up the ladder in either direction (or both).

It can also be useful to remember that the form of the hook and the content of the hook are two different things. For example, in the published adventure Flame Zodge tells the PCs to talk to Tarina, who tells them to go to the Dungeon of the Dead Three. But Zodge could just as easily tell them to go to the Poisoned Poseidon or investigate the dead refugees or question Amrik or even just go straight to Vanthampur Manor.

So even though we’re shifting where the hook points us, we don’t need to abandon the basic structure of the hook.

ZODGE’S BRIEFING: Zodge is actually going to point the PCs in two directions. As detailed in Part 1, he makes a deal with the PCs to investigate the killings:

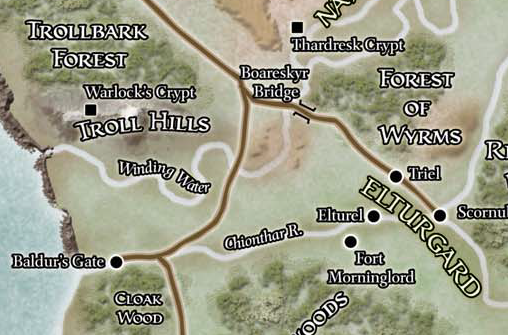

- The city is in chaos. Grand Duke Ulder Ravengard is missing; presumed dead in the fall of Elturel. (He could mention a few Rumors of Elturel he’s heard.)

- Some people blame the Elturians; others think the refugees have a secret agenda; tensions are high, violence is everywhere, and the Flaming Fist is stretched thin trying to keep the city from falling apart.

- Someone is killing refugees. Zodge thinks it’s a coordinated effort, but the Flaming Fist doesn’t have the manpower to mount a proper investigation or response.

- If the PCs agree to investigate the murders and bring the perpetrators to justice, he will immediately allow the refugees from their caravan to enter the city.

- Beyond that, the refugees will be on their own: They’ll have to make whatever arrangements they can. (But it will certainly be better than the refugee camp outside, where conditions are getting more desperate every day.)

Note: If the PCs make exceptionally good time to Baldur’s Gate with their refugees, you may want to have them spend a day or two with the refugees stuck in the camp before Zodge tracks them down (or vice versa) so that there’s enough time for the killings to start.

Once the PCs agree to the deal (or even if they just ask questions), he’ll give them a full briefing:

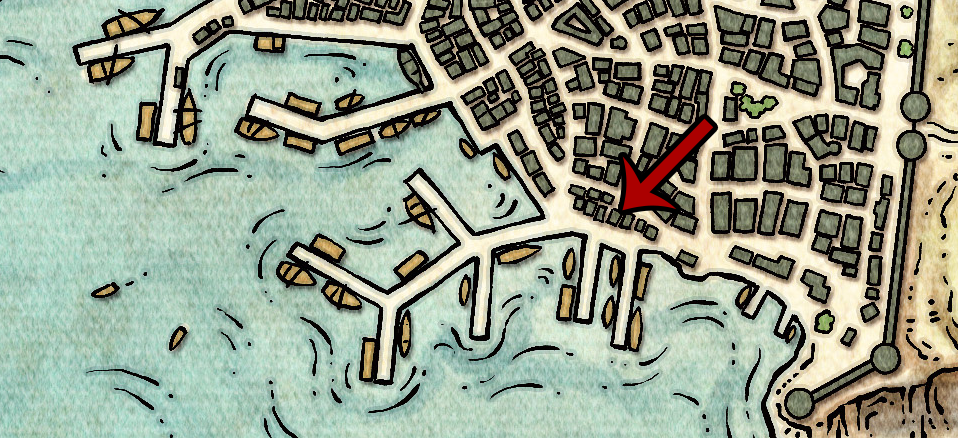

- A half dozen bodies have been dumped in Insight Park, located in the Brampton neighborhood south of Cliffgate.

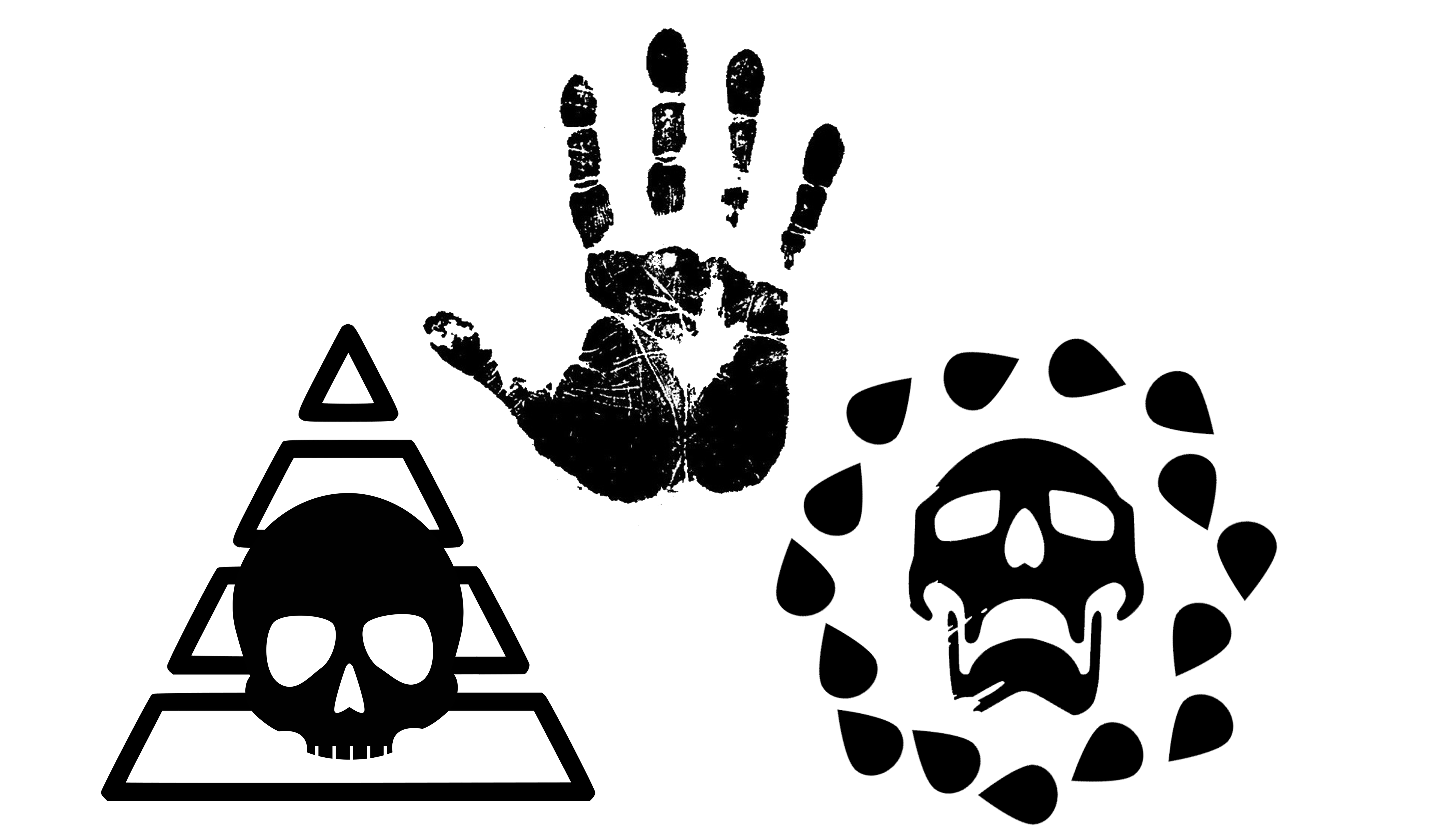

- Ritual symbols associated with the Dead Three – the gods Bane, Bhaal, and Myrkul – have been carved into the bodies. Zodge isn’t sure if it’s actually followers of the Dead Three or if someone is just using them as a scapegoat.

- The PCs are authorized, as deputies, to kill whoever is responsible on sight.

- A Flaming Fist informant named Tarina has sent word to Zodge that she has a lead on the killings. The PCs are to meet at the Elfsong Tavern tonight, find out what she knows, and then follow up on whatever lead she has.

- Zodge gives them a bag with 50gp to pay Tarina for the information.

- They should keep him apprised of their progress.

The briefing actually gives the PCs two leads: They’re likely to go and meet with Tarina, but they could also decide to independently investigate the murders.

TARINA’S LEAD: The lead Tarina gives the PCs in the Elfsong Tavern is straightforward: She’s seen Dead Three cultists around the Poisoned Poseidon in the Brampton docks.

INVESTIGATING THE MURDERS: If the PCs decide to investigate the murders themselves, they have several options. We’ll discuss this in Part 3D.

LEADS (THE SCENARIO SOLVE)

In Advanced Node-Based Design, I talk about the two prongs of mystery scenarios: There are the clues you need to figure out the fundamental truths or revelations about what’s really happening (the concept solve) and there are the clues (or leads) that tell you where to look for more clues (another location or character or event; the scenario solve).

The concept solve is the answer you’re trying to figure out; the scenario solve is what you actually do.

The revelation list for the scenario solve is generally identical (or nearly identical) to the node list. In the case of the Vanthampur Investigations, we have five scenario solve revelations:

- Poisoned Poseidon

- Amrik Vanthampur

- Dungeon of the Dead Three

- Vanthampur Manor

- Infernal Puzzlebox

(The infernal puzzlebox is a scenario solve because it’s the structural link to Part 4: Candlekeep.)

Let’s take a closer look at this revelation list. Because this is a revelation list, we’ll be listing the clues that point to each node; not the clues that are found in those nodes. The location of each clue is indicated in parentheses. (I typically wouldn’t provide descriptions of each clue on a revelation list; but I’m doing so here to make the design process clearer.)

THE POISONED POSEIDON

- Tarina’s Lead. Tarina tells the PCs to go check out the Poisoned Poseidon.

- Tanner’s Fluid (Investigating the Murders). One of the victims has an alkaline solution of wood ash and lime staining her clothes, an alchymical used to rotten and loosen the hair of hides. (The nearest tannery is the Poisoned Poseidon.)

- Staking Out the Murder Scene (Investigating the Murders). When the next corpse is dumped, the PCs can follow the murderers back to the Poisoned Poseidon or question them.

- Amrik’s Paperwork (Trafficking Amrik). Correspondence from Poseidon and notations on the genealogical reports. Amrik can also be questioned to this effect.

AMRIK VANTHAMPUR

- Refugee Papers (Investigating the Murders). Forged refugee paperwork found at the murder scene and on bodies in the morgue can be traced back to Amrik.

- Canvassing Victims (Investigating the Murders). Those who knew the victims can report that they’d been smuggled into the city by Amrik.

- Questioning Mortlock (Dungeon of the Dead Three).

- Assassin’s Orders (Dungeon of the Dead Three). The assassin targeting Mortlock carries a note with instructions from Amrik. The assassin could also be questioned to similar effect.

DUNGEON OF THE DEAD THREE

- Questioning Killers (Investigating the Murders). If the PCs stake out Insight Park, they can question the cultists dumping the bodies.

- Poseidon Correspondence (Poisoned Poseidon). Reports from the Dead Three leadership mention the bathhouse.

- Poseidon Cultists (Poisoned Poseidon). Following or questioning Poseidon cultists can lead to the bathhouse.

- Amrik’s Paperwork (Trafficking Amrik). Amrik is sending reports and receiving instructions from the Dead Three leadership. He can be questioned to similar effect.

VANTHAMPUR MANOR

- Vanthampur Boys (Trafficking Amrik/Dungeon of the Dead Three). Knowing that one or more Vanthampur heirs are involved can be enough to trigger an investigation of Vanthampur Manor all by itself.

- Amrik’s Paperwork (Trafficking Amrik). Amrik has correspondence from his brother Thurstwell.

- Mortlock’s Correspondence (Dungeon of the Dead Three). A letter from his mother detailing how to access the dungeons beneath the bathhouse. Mortlock can be questioned to similar effect.

- Missives of the Hidden Lord (Dungeon of the Dead Three). Correspondence from Thavius Kreeg, passing on instructions from Gargauth to the Dead Three leaders (and inadvertently revealing its presence in Vanthampur Manor).

INFERNAL PUZZLEBOX

- Amrik’s Paperwork (Trafficking Amrik). Amrik’s correspondence with his brother Thurstwell mentions the infernal puzzlebox (Thurstwell has removed it from the family’s vaults where it had been secured because he was fascinated by it).

- Missives of the Hidden Lord (Dungeon of the Dead Three). The missives also mention the puzzlebox.

- Questioning Mortlock (Dungeon of the Dead Three). Mortlock knows that a powerful cult leader escaped from Elturel just before its fall and that his mother is protecting him in the basement of Vanthampur Manor. The cult leader brought two powerful artifacts with him, one of which was locked in a box (or maybe the box is the artifact? Mortlock isn’t sure).

- Finding the Box (Vanthampur Manor). Oh. Hey! There it is!

(If you’re wondering how this revelation list was designed: I literally listed the five revelations and then started adding clues to each one, following the logic of the game world and our intention of being able to follow the leads “up the ladder” in both directions.)

CONCEPT SOLVE

As we’ve discussed previously, there are several core concepts that the PCs should figure out during the Vanthampur Investigations, but which are not actually required for them to proceed:

- The murder victims are descended from knights of Elturgard (either Hellriders or the Order of Companions).

- The Shield of the Hidden Lord is hidden in Vanthampur Manor. (Ideally, this results in them finding and taking the shield.)

- Thavius Kreeg is a cultist.

- Elturel was destroyed by devils.

VICTIMS DESCENDED FROM KNIGHTS OF ELTURGARD

- Canvassing Victims (Investigating the Murders). In speaking with those who knew the victims, the fact that they either were knights or were related to them will be a common theme players might notice. One victim is notably NOT a refugee; in their house hangs the mantle of a Hellrider (their father’s).

- Amrik’s Paperwork (Trafficking Amrik). His paperwork includes the genealogical records he’s cross-referencing.

- Missives of the Hidden Lord (Dungeon of the Dead Three). The missives also reveal that the Dead Three cultists must “seek the blood of the holy orders of Elturgard.”

- Thurstwell’s Correspondence (Vanthampur Manor). Includes queries from Amrik regarding Thurstwell’s efforts to assist him.

GARGAUTH / SHIELD OF THE HIDDEN LORD

- Interrogating Cultists (Dungeon of the Dead Three). They know the history of Gargauth and know that the Vanthampurs hold the Shield of the Hidden Lord.

- Missives of the Hidden Lord (Dungeon of the Dead Three). Name says its all.

- Questioning Mortlock (Dungeon of the Dead Three). Mortlock knows that a powerful cult leader escaped from Elturel just before its fall and that his mother is protecting him in the basement of Vanthampur Manor. The cult leader brought two powerful artifacts with him, one of which was a shield in the likeness of a demonic face.

- Finding the Shield. Oh. Hey! There it is!

KREEG’S A CULTIST

(Most of these clues are more oblique. It’s fairly possible for the PCs to NOT realize that Kreeg is a cultist, instead “rescuing” him from the Vanthampurs.)

- Amrik’s Paperwork (Trafficking Amrik). The genealogical records Amrik is using come from Thavius Kreeg’s office in Elturel.

- Missives of the Hidden Lord (Dungeon of the Dead Three). These are signed with the initials “TK.”

- Questioning Mortlock (Dungeon of the Dead Three). Mortlock knows that a powerful cult leader escaped from Elturel just before its fall and that his mother is protecting him in the basement of Vanthampur Manor.

- Encountering Kreeg (Vanthampur Manor). Uh… Hi. Nice to meet you. Whatchu doin’ down here?

ELTUREL WAS DESTROYED BY DEVILS

- Rumors of Elturel

- Altar Prophecies/Adulation (Dungeon of the Dead Three). Tales and prophecies of Elturel’s fall can be found in the chapels of the Dead Three.

- Questioning Gargauth, Kreeg, or Duke Vanthampur (Vanthampur Manor). All three of these NPCs know the truth (that Elturel was taken to Hell). All three of them will lie obliquely, referring to Elturel’s Fall and — if pushed to it! — that the legions of Zariel “fell upon the city” (and similar euphemisms).

PORTYR POLITICS

The last thing I want to layer in here is the wider impact of current events in Baldur’s Gate: In addition to the refugee crisis itself, the emerging ducal politics of  how the power vacuum left by Grand Duke Ravengard’s apparent death is going to shake out is not only really interesting, it’s also immediately relevant to Duke Vanthampur’s schemes.

how the power vacuum left by Grand Duke Ravengard’s apparent death is going to shake out is not only really interesting, it’s also immediately relevant to Duke Vanthampur’s schemes.

As the campaign begins, you have the position of Grand Duke, an empty ducal seat, AND Marshal of the Flaming Fists all up for grabs. These might go to the same person OR three different people. Then, over in the Adventurers’ League scenarios, Duke Portyr is assassinated just AFTER putting his niece in a position where she might be able to become Marshal of the Flaming Fists.

Can she consolidate that position? Or does the whole Portyr power base fall apart?

How can we bring this into the campaign? How can we give the PCs (and players) a window into what’s happening?

Our mechanism is going to be Zodge. We have five potential interactions with Zodge (when he hires them and then once after each of the four nodes in the Vanthampur Investigations as the PCs check in with him), and we’re going to use them like this:

FIRST INTERACTION. Zodge hires them.

SECOND INTERACTION. Blaze Portyr has arrived in Baldur’s Gate. It’s probably most dramatic for her to sweep into Zodge’s office while the PCs are in the middle of briefing him, but maybe she’s already in situ discussing strategy with him when the PCs show up.

See the “Topics of Conversation” in Part 2B and figure out how many of the rumors about rival claimants to the position of Marshal are true. (Could be all of them, could be none of them, or anything in between.) Portyr’s current agenda is securing the allegiance of Flames (like Zodge) in her own bid for Marshal.

It’s important to establish that Blaze Portyr is the niece of Duke Portyr in this scene. You can do that by having Zodge say something like, “I’m assuming your uncle is supporting you? Duke Dillard’s political backing will make the difference in the Upper City.” (But whatever works.)

Tip: Either way, Zodge won’t have had time to brief Portyr on the PCs’ investigation. When Portyr wants to know what’s going on, have her ask the PCs instead of Zodge. Let your players brief her in: Not only does it make them the active protagonists of the interaction; it will also be a great way to organically make them remind themselves of what they know and what their goals are.

If you want the players to like her, have her enthusiastically endorse Zodge’s initiative in seeking justice for the refugees.

THIRD INTERACTION: This interaction is optional, or it might happen after the Fourth Interaction, depending on the sequence in which the PCs go to the various nodes and whether or not they check in after each node. Portyr and Zodge are still plotting together.

- She’s declared herself Marshal.

- Flame Zodge has been promoted to Blaze.

- One of the rivals established in the Second Interaction has been eliminated. (For example, Blaze Beldroth has been arrested. Or Blaze Mukar of Wyrm’s Rock has sworn allegiance to Portyr. Or she’s gained the Eltan family’s support by having her uncle buy back their shares in the Flaming Fist for them.) Even if you’re going with the “lots of rivals” options, only have one of them get resolved here. (It’s a project in progress, not the whole enchilada.)

FOURTH INTERACTION: At the end of Part 3F: Dungeon of the Dead Three, we’ll discover that Duke Vanthampur has ordered the Dead Three cultists to assassinate Duke Portyr. The PCs rush to the political rally where Duke Portyr is being targeted, but they’re almost certainly too late.

When Marshal Portyr learns that Duke Vanthampur is responsible for her uncle’s death, she asks the PCs to wipe out the Vanthampur family. For political reasons, they’ll be disavowed. But if they succeed, she’ll offer them either promotions within the Flaming Fist or a big cash reward (whatever appeals to them more).

Note: It’s a relatively minor thing, but in the adventure as published it’s a little odd that the PCs are assumed to murder one of the Four Dukes and the response of the Flaming Fist is a collective shrug. Here we’ve contextualized the action within the general political crisis in the city (all of it flowing directly out of Elturel’s disappearance and the loss of the Grand Duke) and also given the PCs’ a clear agenda heading into Vanthampur Manor.

FIFTH INTERACTION: After the PCs assassinate Duke Vanthampur, Marshal Portyr will suggest/encourage/support them getting out of Baldur’s Gate for awhile until the political complications arising from Vanthampur’s death are settled. (More details on this in Part 4: Candlekeep.)

Note: When the PCs get back from Hell and bring a probably totally still alive Grand Duke Ravengard back to Baldur’s Gate only to discover that he’s been “replaced”… Well, that’s when politics are going to get REALLY interesting.

ALTERNATIVE HOOK

In Part 2B, I mentioned the possibility of the PCs figuring out an end-run around Flame Zodge and using the murder of one of their refugees to pull them into Part 3D: Investigating the Murders as an alternative hook to the campaign.

If you use this alternative hook, does it mean you miss out on the Portyr Politics?

Not necessarily.

First, if the PCs have avoided Zodge entirely, he might get wind of their investigation after the first or second node they’ve explored. He might approach them directly or through Tarina (who is most likely to have identified the PCs) to figure out what they’re up to (and potentially bring them onboard in an official capacity).

Second, if the PCs turned down Zodge’s offer, they’re still likely to run into Marshal Portyr after her uncle has been assassinated. She’ll want to know what their investigation has uncovered so far, and you should be able to weave in a few details of her current schemes to secure control of the Flaming Fists into the resulting scene.

Failing all that, these events will still provide some great background events for bringing Baldur’s Gate to life.

Go to Part 3D: Investigating the Murders

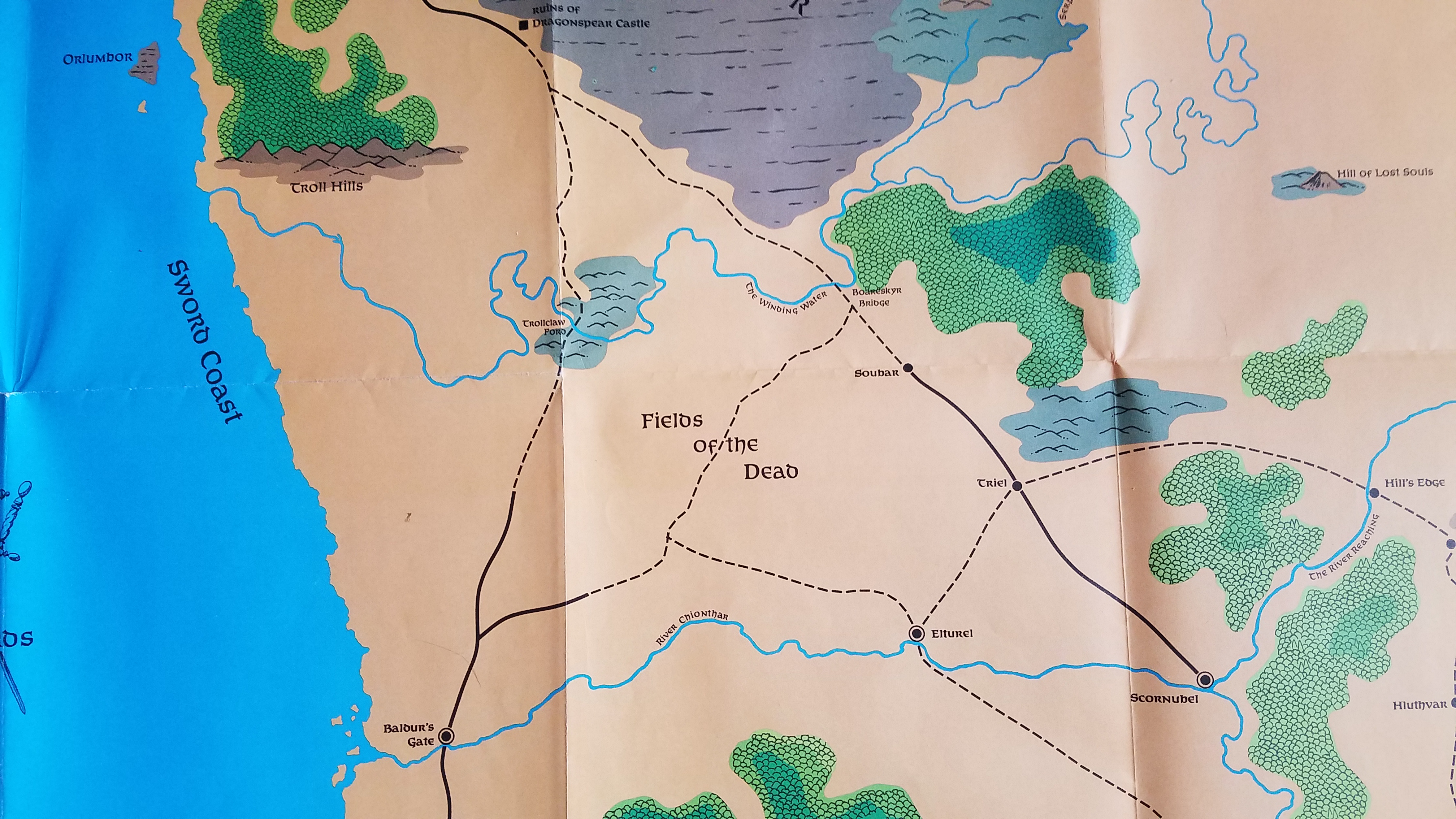

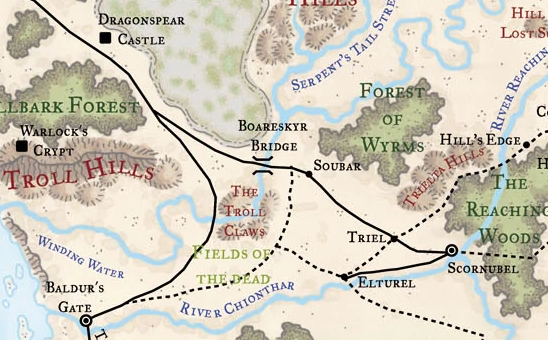

![[Elturel] has been seeking ways to unseat Scornubel as the major trading town on the Trade Way between Waterdeep and Iriaebor.](https://www.thealexandrian.net/images/20200417i.png)