In “On the Use of GM Screens” a few years back I shared my personal best practices when it comes to using GM screens. Probably the biggest reason I like them is the vertical reference space: One of my secret weapons as a GM is simply arranging my reference material so that I can lay out multiple elements (stat blocks, room descriptions, campaign status document, maps, NPC roleplaying templates, etc.) simultaneously. I can thus cross-reference material by just flicking my eyes back and forth, and can often easily compare information directly instead of having to flip back-and-forth.

The vertical reference space of the GM screen, therefore, is basically free space. I’ve already covered every inch of table space in front of me (and often have a TV tray to one side for additional reference material), so basically creating more space in the third dimension is a huge advantage.

Now, the most common thing I put in that vertical space is my system cheat sheet. It’s virtually always useful when running a game, and putting that information into the vertical plane means that my horizontal surfaces can be focused on scenario-related material. These cheat sheets can also be prepped ahead of time

But this is not the only way you can utilize that vertical space! This is a trick that I didn’t think to include in “On the Use of GM Screens” because I don’t use it very often, but it can be very effective upon occasion and you may find it even more useful than I do.

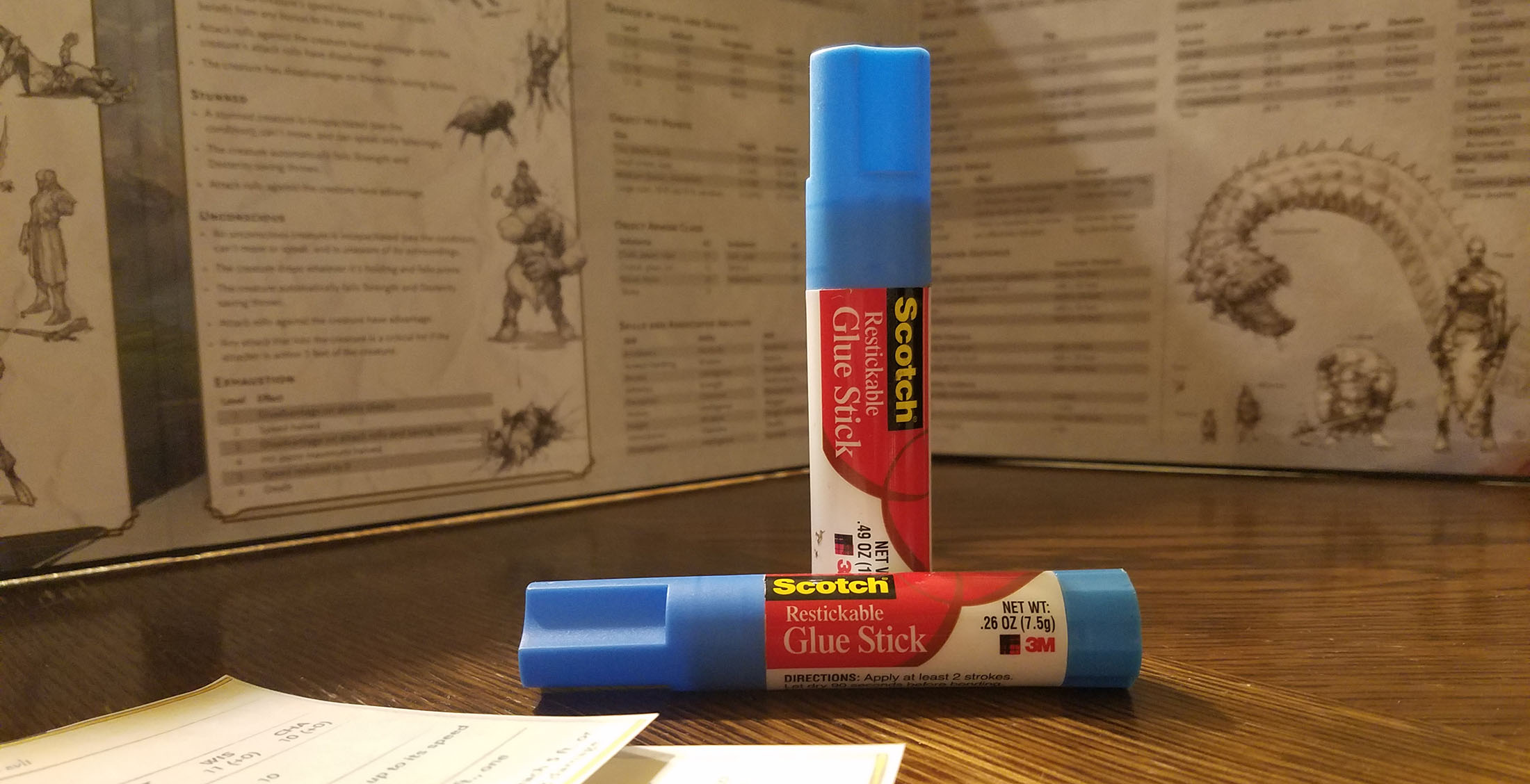

Basically, 3M makes these removable restickable glue sticks:

They can be used to essentially turn any piece of paper into a Post-It note. And that, in turn, means that you can turn any piece of paper into a swap note that you can quickly paste up or remove from your GM screen.

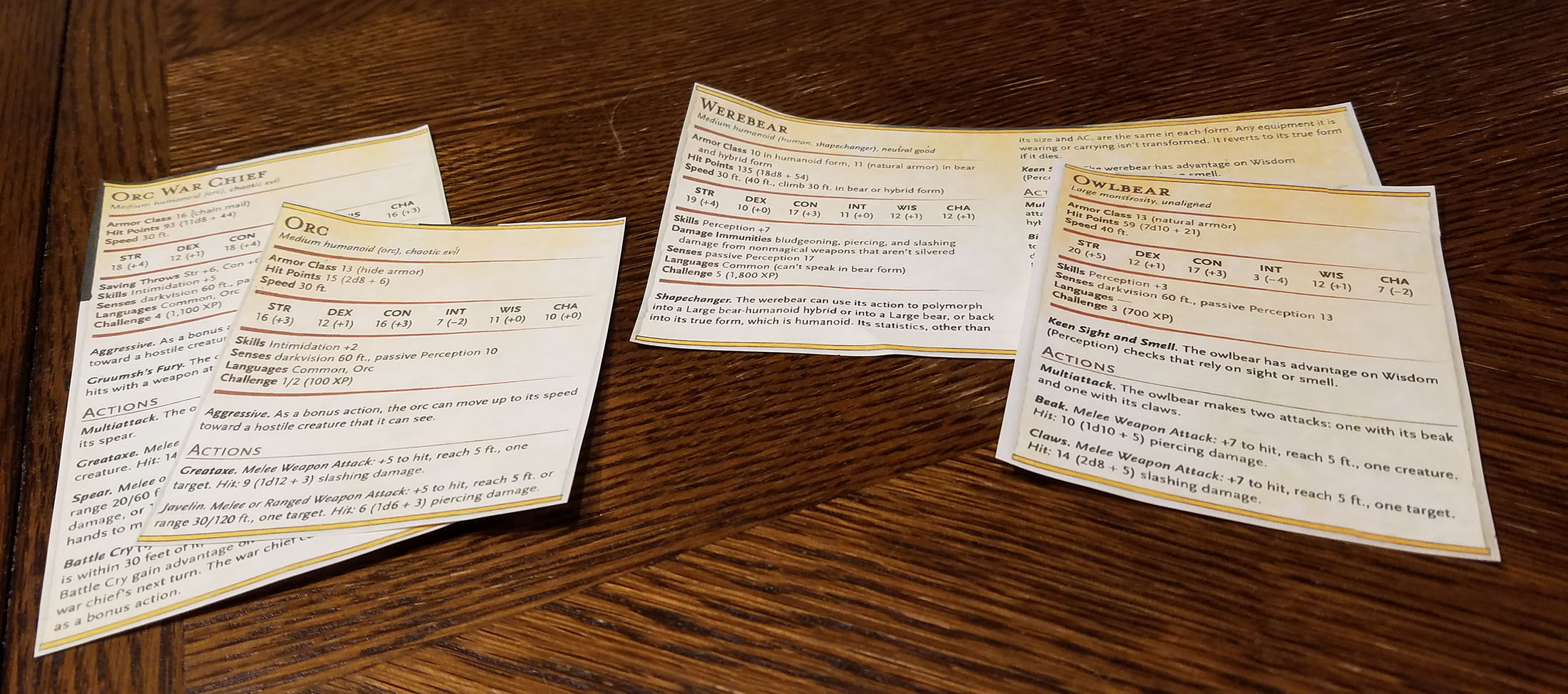

For example, you can print out the stat blocks for your current scenario. Here I’ve grabbed an Orc War Chief accompanied by a warband of Orcs, and also a second encounter featuring a Werebear and his pet Owlbear:

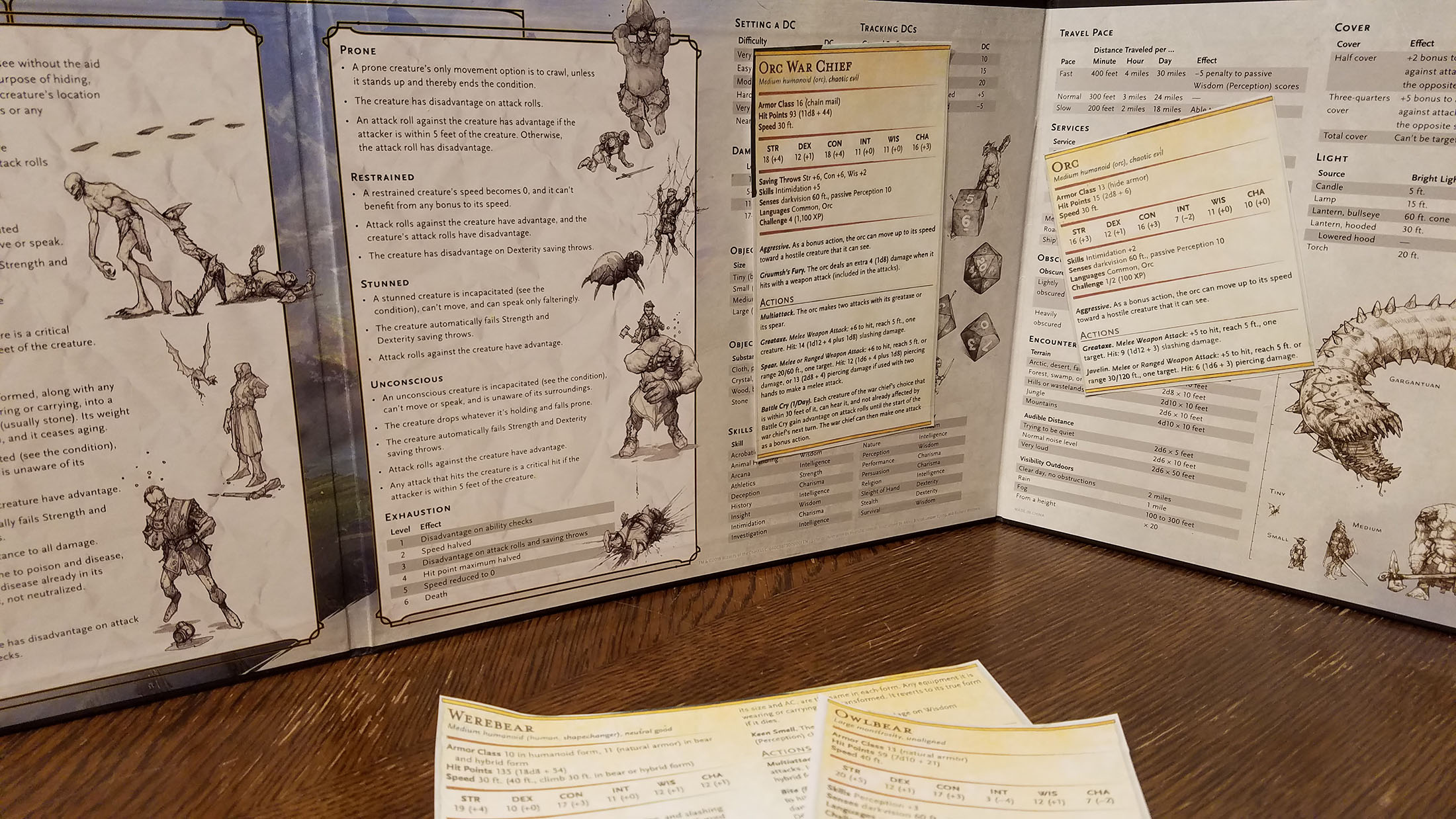

And then, while running the game, you can quickly use the restickable glue stick to attach them to the GM screen for easy reference during an encounter:

Other stuff that you might find useful as a swap note:

- A list of upcoming, timed events for the current session that you don’t want to forget

- The map of the dungeon

- NPCs in the current scene

- The standard features (door types, ceiling height, light sources, environmental effects) of the current dungeon

- The daily weather forecast for the next several days of a sandbox campaign (so that you don’t forget to make it rain)

As I’ve talked about before, what reference material a GM finds useful will often be very specific to that GM, and will often change over time. So experiment with different options, and pay attention to the type of information that you had to stop and scramble for (or just really wish you’d had handy) during your last session.

You can also just keep a straight-up stack of Post-Its that you can scribble out transient-yet-important information onto.

This is also works on the other side of the screen, too! If you have visual references for the players (like, say, all those photo handouts that are part of the Alexandrian Remix of Eternal Lies), you could similarly turn them into Post-Its and slap them onto the front of the screen. If you’re going to do this a lot, it might argue for using a simple pattern for the player’s side of your screen. You could even go for a collage approach, where instead of removing the references you just keep layering them on top of each other, creating an ever-evolving visual motif of the campaign that continues to grow as the campaign goes on.

PROVISOS

In my experience, this technique only works passingly well with the old, thin cardboard-style screens. But it works great with the modern, glossy, board-stock screens that have become de rigeur. It works even better with modular screens like those from Pinnacle, Strategem, and Hammerdog.

You don’t want to leave the notes attached for an extended period of time. I first used this technique with my Eclipse Phase screen and I ended up leaving a few swap notes attached when we moved on to other games. When I opened the screen up a couple of years later, I found that the glue had chemically deteriorated and left a chalky residue that was difficult to clean up.

have collaborated on a scenario built around

have collaborated on a scenario built around