Goat-ball is a team sport similar to dodgeball that’s played by goliaths. It uses a furry, misshaped ball made of stuffed goat hide and also requires a dozen or more elevated platforms (usually pillars, boulders, or tree stumps) arranged in a random pattern. Two teams leap from platform to platform, pass the ball back and forth, and try to knock their opponents off their platforms.

STARTING THE GAME: Traditionally, the ball is kicked into play by a goat and the two teams try to catch it to gain first possession. It’s not unusual, though, for a referee to throw the ball into play instead.

POSSESSION: The possessing team’s goal is to complete three passes between teammates standing on four different platforms. (You can’t just pass it back and forth between the same platforms.) Once you’ve completed three passes, the ball becomes hot. You can throw a hot ball and strike a member of the opposing team to knock them out of play. (This is referred to as a knock off even though the player does not have to be physically knocked off their platform by the throw.) If the hot throw is successful (i.e., it knocks off a member of the opposing team), the ball is placed on the platform of the player who was knocked off and remains hot and in the possession of the throwing team.

CHANGE OF POSSESSION: If the ball is intercepted, the ball hits the ground, or the player holding the ball hits the ground, the other team gains possession of the ball. (The ball is given to a player of that team’s choice.)

KNOCK OFFS: A player who is struck by a hot ball or who touches the ground for any reason is knocked off. They are eliminated from play until a change of possession.

WINNING: A team loses when all of their players have been eliminated. The last surviving team wins the game.

Note: The game is usually played by two teams, but “thunder scrums” featuring multiple teams all playing against each other at the same time can also be played.

GOAT-BALL MECHANICS

A game of goat-ball is divided into rounds, with each round being referred to as a pass.

STARTING THE GAME: When the goat kicks the ball, all players make a Dexterity (Acrobatics) check. The highest result gains possession. In the case of a tie involving multiple teams, have the tied characters roll off with an additional Dexterity (Acrobatics) check.

INITIATIVE: In each pass, the players roll initiative and declare their intended actions in reverse initiative order.

The current ball carrier makes their action declaration in secret (writing it down on a piece of paper and revealing it only after all other actions have been declared). If they are attempting a Throw, they must indicate who they are throwing the ball to or at.

ACTIONS: Characters who have been knocked off cannot take an action in the game until a change of possession allow them to rejoin the action.

- Throw: Players on the team which has possession can participate in the Throw. Every player participating in the throw makes a Strength (Athletics) or Dexterity (Acrobatics) check (their choice) vs. DC 5. On a failure, they have fallen off. On a success, add the margin of success to the throw total.

- Intercept: Players on the opposing team can attempt to intercept. Every player taking the Intercept action can make a Strength (Athletics) or Dexterity (Acrobatics) check (their choice) vs. DC 5. On a failure, they have fallen off. On a success, add the margin of success to the intercept total.

- Knock-Off: You can attempt to physically knock off a member of the opposing team by making a Strength (Athletics) check contested by the target’s Strength (Athletics) or Dexterity (Acrobatics) check (the target chooses the ability they use). On a success, you knock them off. If the ball carrier is knocked off, the pass immediately ends and possession changes. If the target of the current Throw is knocked off, the Throw automatically fails.

- Defend: You can take a Help action to grant advantage to a character targeted by a Knock-Off action.

PASS: If a pass was attempted, compare the throw total to the intercept total. If the throw total was higher, the pass was successful and the target becomes the new ball carrier. If the intercept total was higher, the opposing team has gained possession and the character with the highest Intercept check result that round becomes the new ball carrier. (In practice, this might be due to an actual interception or the ball may have simply hit the ground.)

HOT THROWS: If three passes have been successfully completed by the possessing team, they can instead attempt a hot throw to knock out an opposing player. This is resolved like a pass, but if the throwing team succeeds, the ball carrier can make a Dexterity (Acrobatics) check with advantage opposed by the target’s Dexterity (Acrobatics) check. On a failure, possession changes. On a success, the target is eliminated and the throwing team retains possession. (In either case, the possessing team chooses the new ball carrier.)

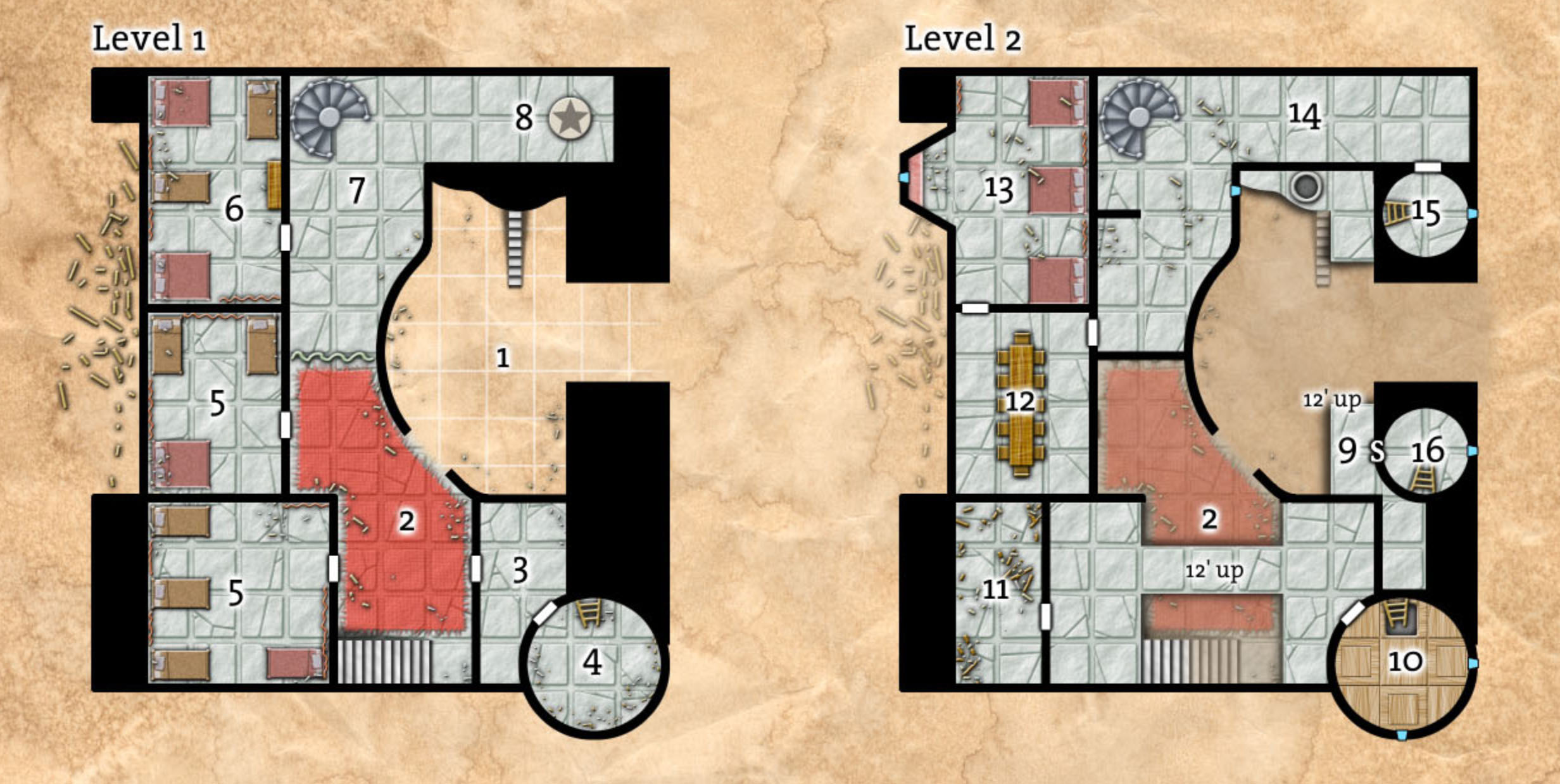

OPTIONAL RULE: ZONES

For the purposes of resolution, you can break the field of play up into multiple zones.

- Move: Players can Move to an adjacent zone as an action.

- Throw / Intercept: Being in the same zone as the ball carrier or target grants advantage on throw and intercept checks.

- Knock-Off / Defend: You must be in the same zone as the target to attempt a Knock-Off or Defend action.

- Block: A player can attempt to block opposing players from entering their zone.

Design Note: I’m not sure what the right number of zones is. I think the sweet spot might be roughly three times as many players as zones, but it needs some playtesting.

OPTIONAL RULES: QUICK RESOLUTION

To quickly resolve a goat-ball game, simply have all the players on each team make either a Strength (Athletics) or Dexterity (Acrobatics) check (their choice). Add up the total score for each time. The team with the highest total wins. In the event of a tie, the team whose player had the highest single untied check result wins. If the result is still a tie, the game ends in a draw after several exhausting hours of play.

BLOOD-BALL

Blood-ball is a variant of goat-ball in which the ball is replaced with a spear. The rules remain the same, except, of course, that getting knocked off by a spear throw can often be a lethal experience. In some cases, any knock-off is lethal in blood-ball (with all such players being executed).

Blood-ball is usually only played to resolve the most serious of clan rivalries or disputes. It may also be played as gladiatorial sport by smaller races in the decadent south (which goliaths find distasteful).

EMPOWERED GAMES

Goat-ball is usually a contest of purely physical skill, but some goat-ball games allow the use of spells or supernatural abilities. In some cases this is limited to a specific set of magical abilities. Lethal spells are usually banned (with the exception of blood-ball matches). Flying is always banned, since it largely negates the whole point of the game.

Note: Empowered games are rarely played and blood ball is never played at Wyrmdoom Crag, but they’re the kind of thing youngsters gossip about in scandalous whispers.

Some of these clues will likely be quite straightforward: For example, the key in Room 11 that opens the door in Area 41.

Some of these clues will likely be quite straightforward: For example, the key in Room 11 that opens the door in Area 41.