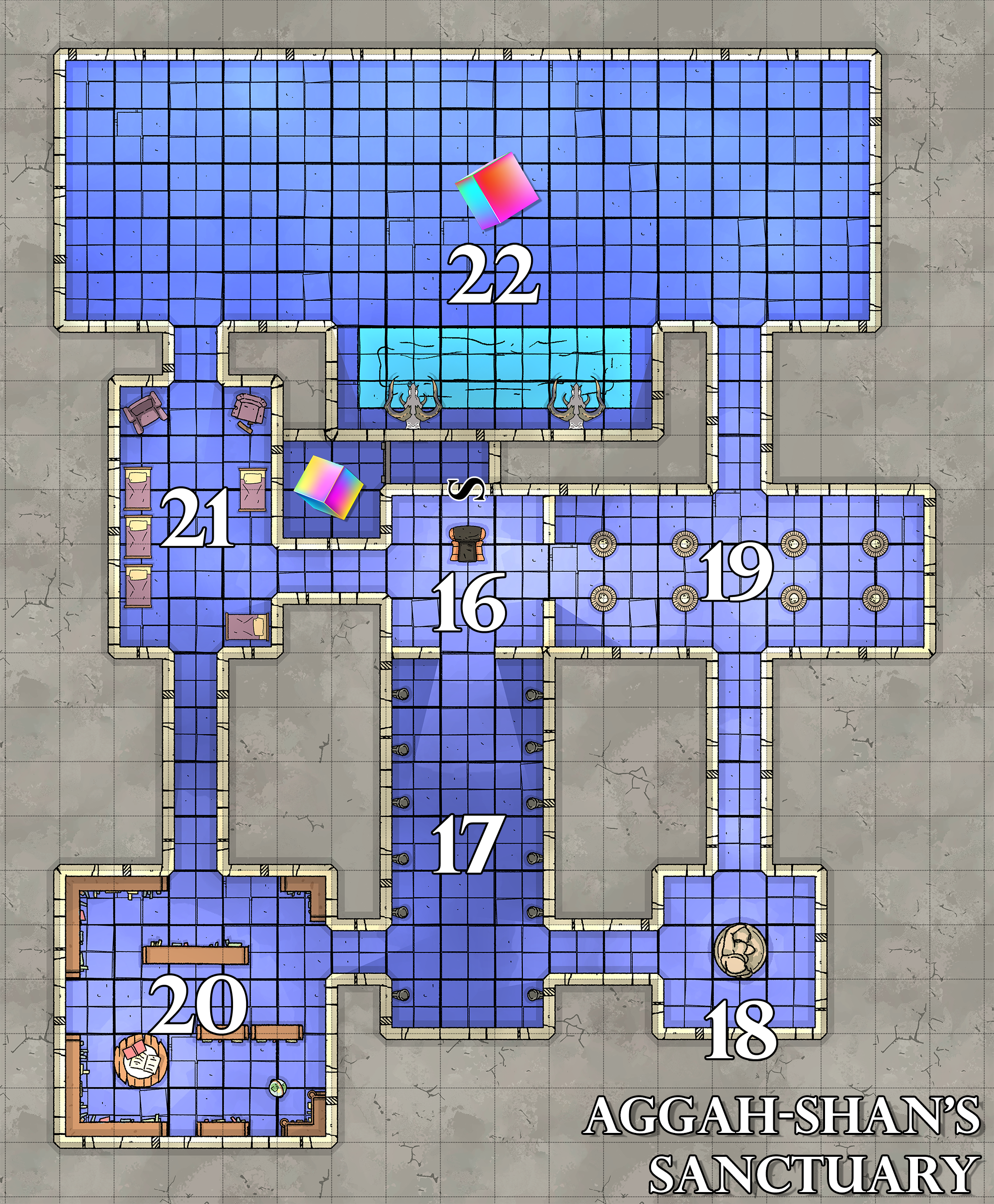

AREA 10 – LOWER ANTECHAMBER

A chamber of white, blue-veined marble. The walls, floor, and ceiling are lightly rimed with frost.

There are 6 wights (MM, p. 300), 2 ghasts (MM, p.), and 2 frostbanes.

DOOR TRAP: Any living creature touching the door leading to the hallway triggers a cloudkill that fills the room for 10 minutes.

- Magical trap

- DC 16 Intelligence (Investigation) to detect.

- DC 16 Dexterity (Thieves’ Tools) to disable.

AREA 11 – GORGON GUARDS

The walls and ceiling of this chamber are painted sky blue with blood-red clouds.

Standing guard upon a pair of double doors crafted from glistening ebony are 2 gorgons (MM, p. 171).

AREA 12 – THE IRON THRONE

A long red carpet leads up to a small dais on which sits a throne of stone and iron.

THRONE: The throne is designed to teleport its user to Area 16 (in Aggah-Shan’s Sanctum). To operate the throne, the user must strap themselves into it. During the teleport, carefully positioned spikes sprout from the chair, inflicting 20d6 points of damage (no save). (The spikes pass harmlessly through a skeletal figure.)

- Mechanical trap

- DC 11 Intelligence (Investigation) to identify the trap.

- DC 14 Intelligence (Arcana) identifies the teleport properties of the throne.

- DC 20 Dexterity (Thieves’ Tools) to disable the spikes (but this also disables the teleport effect).

TELEPORT TRACE: Aggah-Shan has blocked divinations leading to his sanctuary, but if he has recently used the chair (25% chance) a teleport trace or similar effect will reveal the chair’s destination.

AREA 13 – ADAMANTINE SKELETONS

The vault (Area 14) is guarded by 4 adamantine ettin skeletons.

VAULT DOOR (10-in. iron): AC 19, 300 hp, DC 24 Dexterity (Thieves’ Tools)

ADAMANTINE ETTIN SKELETON

Large undead, lawful evil

Armor Class 14 (natural)

Hit Points 85 (10d10+30)

Speed 40 ft.

STR 21 (+5), DEX 10 (+0), CON 17 (+3), INT 2 (-4), WIS 10 (+0), CHA 4 (-3)

Skills Perception +4

Senses darkvision 60 ft., passive Perception 14

Damage Immunities poison; bludgeoning, piercing, and slashing from nonmagical attacks that aren’t adamantine; critical hits become normal hits

Condition Immunities poisoned, exhaustion; can’t be poisoned

Languages Giant, Orc (can’t speak, but can understand)

Challenge 5 (1,100 XP)

Proficiency Bonus: +2

Two Heads. The ettin skeleton has advantage on Wisdom (Perception) checks and on saving throws against being blinded, charmed, deafened, frightened, stunned, and knocked unconscious.

ACTIONS

Multiattack. The ettin skeleton makes two adamantine claw attacks.

Adamantine Claw. Melee Weapon Attack: +7 to hit, reach 5 ft., one target. Hit: 14 (2d8+5) slashing damage. This counts as an attack with an adamantine weapon, automatically dealing a critical hit to objects.

AREA 14 – FALSE VAULT

This outer vault contains:

- 3,113 gp

- amber gold earring (525 gp)

- ceremonial electrum dagger with star ruby pommel (930 gp)

- death mask of beaten gold (85 gp)

- gold medallion with black opal gemstone (1,500 gp)

- golden sphere (75 gp)

- heavy wrought gold bracelet (650 gp)

- beaded headdress (100 gp)

- ornamental silver skullcap, inclaid with runes and a moonstone set above the brow (315 gp)

- small gold statuette of a maiden on a unicorn (175 gp)

- potion of restoration

- heavy crossbow +2

- dagger +1

Playtest Tip: There are two reasons for the specificity in Aggah-Shan’s vaults. First, it makes looting the place cooler than just “you find 4,355 gp in jewelry.” Second, because Aggah-Shan isn’t on site, the likely outcome of any heist here is that he — and his organization — will be looking for the PCs. Each item can be targeted by divinations. Each item the PCs fence can be traced. Each item gives a vector for continuing the scenario by other means.

SECRET DOOR: DC 25 Intelligence (Investigation). Panel slides away to reveal a second vault door. Moving the panel without applying pressure to the correct sections triggers a trap. A gemstone inset on the vault door shoots out 1d4+1 beams of purple-black energy, targeting any characters in line of sight (starting with those closest).

- Magical trap

- Melee Spell Attack: +12 to hit, one creature. Hit: Life drain, dealing 10d10 necrotic damage. The target must succed on a DC 16 Constitution saving throw or its hit point maximum is reduced by an amount equal to the damage taken. This reduction lasts until the creature finishes a long rest. The target dies if this effect reduces its hit point maximum to 0.

VAULT DOOR (10-in. iron): AC 19, 300 hp, DC 24 Dexterity (Thieves’ Tools).

AREA 15 – TRUE VAULT

The inner vault contains:

- 1,000 pp, 4,300 gp, 8,765 sp

- Gems: violet apatite (50 gp), graveyard plume agate with white flames (60 gp), block of green jade (125 gp), rusteen (210 gp), 25 peach sunstones (10 gp each), 25 red sunstones (10 gp each)

- Potions: giant strength, healing, endure elements (x2), enlarge, magic weapon, spider climb

- Scrolls: alter self, levitate, blur, jump, mage armor, minor illusion, shield, mirror image, charm person, conjure animals, summon fey

- horn of goodness/evil (wrought from a bicorn’s fluted horn of white and black)

- horn of Valhalla (this specific horn is tied to the ancestors of the Grey Mountain barbarians who are marching on Ptolus, see Night of Dissolution, p. 5)

- horn of silence (advantage on saving throws against sonic effects when held; 1/day create silence spell that can be dismissed with a second blow; 1/day create the effect of a shatter spell)

- (75% chance) adamantine arrow keyed to the ley-laced marble statue in Area 18. (If it’s not here, then Aggah-Shan has it.)

- Book of Lesser Chaos and Book of Greater Chaos

HORN OF GOODNESS/EVIL

This trumpet adapts itself to its owner, so it produces either a good or an evil effect depending on its owner’s alignment. If the owner is neither good nor evil, the horn has no power whatsoever. When the horn is blown, it produces the effects of a magic circle spell. If the owner is good, they can choose for the circle to be effective against fiends or the undead. If the owner is evil, they can choose for the circle to be effective against celestials. The horn can be blown once per day.