IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

SESSION 28B: ON THE EVE OF THE BANEWARRENS

September 14th, 2008

The 15th Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

TAVAN ZITH AT CASTLE SHARD

They left. Once they were safely in the carriage and driving away from the Cathedral they talked things over.

“I don’t trust him,” Tor said.

Dominic nodded. “You can put crimson robes on a pig, it’s still not a novarch.”

They needed to know more. They needed to question Tavan Zith, and the only way they could think to do that was by going to Castle Shard. They also needed to know if Lord Zavere was the one responsible for opening the Banewarrens. And, if so, why.

As they rode, Dominic looked at the others. “So… do we have any idea how we’re going to do this without getting killed?”

Agnarr shrugged. “Sure. We ask him. If he didn’t do it, we don’t get killed.”

Tor came up with a better strategy. “We tell him that we respect him. Tell him we’ve been approached about this. But if he’s involved, we’re more than happy to stay out of it. We just want to know that before getting in his way.”

Kadmus was waiting for them at the gate of the castle. He ushered them in to see Lord Zavere. He welcomed them warmly and seemed genuinely pleased to see them.

Unfortunately, their plan fell apart fairly quickly. Tee carefully began working her way around the subject of the Banewarrens – sounding him out on the matter. But then Elestra blurted out Rehobath’s involvement. Before Tee could regain her grip on the situation, Zavere had quickly figured out that they had been approached by both the Novarch and the Inverted Pyramid.

Tee sighed and decided to make the best of it.

“What do you know about the Inverted Pyramid? Should we trust them?”

“It depends,” Zavere said. “Although I have reasons to distrust them, the Pyramid is not entirely monolithic. Whether you can trust them will most likely have more to do with whether or not you can trust the person you’re working for.”

“And what do you know about the Banewarrens themselves?”

Zavere gave them a brief history similar to the one Jevicca had described to them. “No one has ever been able to penetrate them, although many have tried. It’s known that Ghul himself was fascinated by them. He named himself the Sorcerer’s Get and claimed to be a direct descendant of the Banelord himself. The drill I purchased from you would have been only one of many attempts he made to access them.

“Much of our modern knowledge of them derives from records recovered by Gerris Hin, the same loremaster responsible for founding the modern city of Ptolus. Over the centuries, many have attempted to succeed where Ghul failed. Some of them, like Sokalahn, being quite famous. Others less so. But whether powerful or clever, none have ever succeeded.”

“And have you ever tried?”

Zavere laughed. “No. I purchased the drill as a mere curiosity. I doubt it would work in any case. No, the Banewarrens are not a specialty of mine.”

“Do you know who might specialize in it?” Tor asked.

“The Banewarrens have long been a fool’s errand. If you had asked me yesterday, I might have told you that no one was studying it. But clearly the last few hours have changed that.”

“If the Banewarrens have been opened,” Tor said, “I don’t know if we’re strong enough to face them.”

“Neither do I,” said Zavere. “But I will look in the archives of the Castle. If they contain any information about the Banewarrens that might help you, I’ll let you know.”

“Thank you,” Tor said.

“There is something else…” Tee said hesitantly, glancing at the others. “Does the name Tavan Zith mean anything to you?”

It didn’t. Tee quickly filled him on what had happened and showed him the prophecy they had discovered in Pythoness House. Then she revealed that they had Tavan Zith in custody, but had been unable to question him. She let Ranthir explain why and share his theory about how an antimagic field might be used to suppress Zith’s ability.

“Where is he now?” Zavere asked.

Tee glanced nervously at her bag of holding. Zavere followed her gaze.

“Are you serious?”

Tee nodded.

“Very well. Come with me.”

Zavere led them through the Castle, taking them to a small, but well-accoutered laboratory where Lady Rill was working. He quickly explained the situation to her.

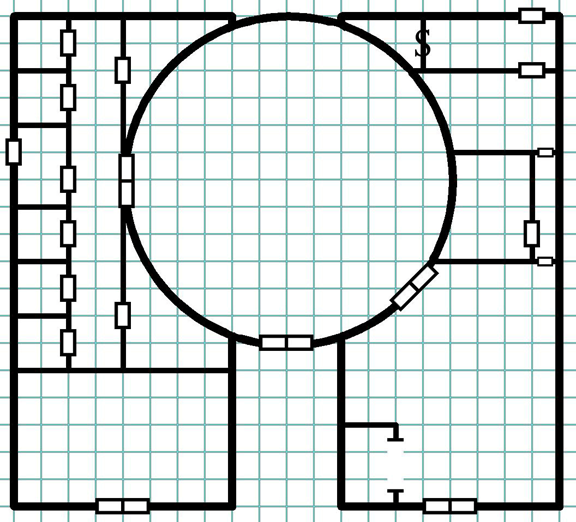

Lady Rill lowered a metal cylinder out of the ceiling. Manipulating several devices she created a blue, glowing field of energy within the cylinder. “If you place him in there, he will be restrained and any sorcerous manifestations will be suppressed.”

Tee removed Zith from her bag of holding and placed him in the cylinder. They woke him up.

As Zith opened his eyes, his features contorted into a contemptuous sneer. “The powers of chaos shall make you rue this day.”

“Who are you?”

“I am the sower of chaos! The servant of the true gods!”

“What do you mean?”

“Destruction. Destruction is the ultimate end of all things and the fulfillment of all dreams.”

“Do you know where the Banewarrens are located? Did you come from the Banewarrens?”

But his answers were useless, varying between the megalomaniacal and the insane. After several minutes they gave up. Zavere promised to continue questioning him, although he had little hope of getting anything out of him. They thanked him and Lady Rill both and went on their way.

ON THE EVE OF THE BANEWARRENS

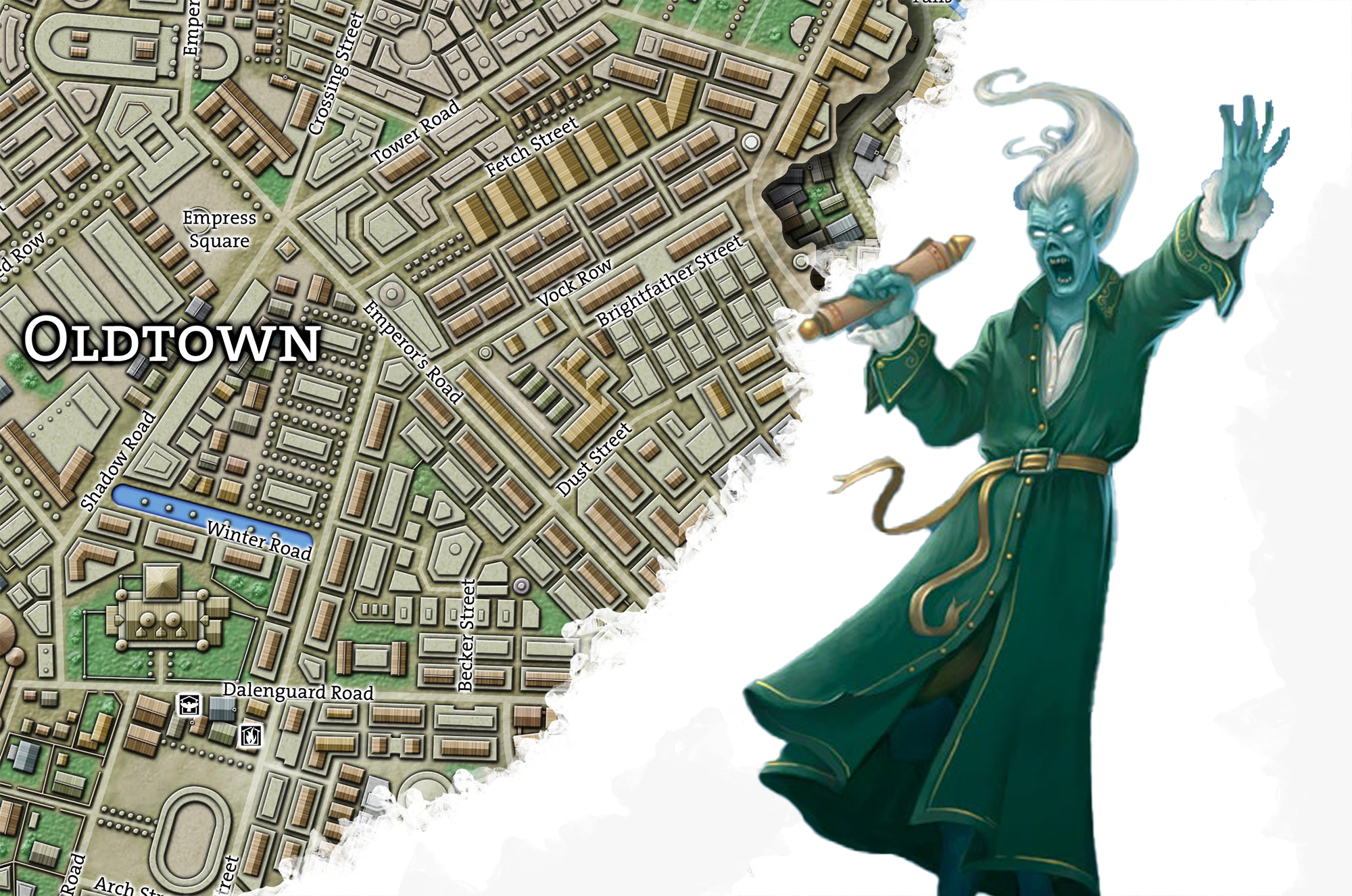

As they passed down through Oldtown they turned aside long enough to stop at the Pale Tower. There Tee left word with the Graven One – asking if any of the Malkuth would be interested in knowing that the Banewarrens had been opened.

Ranthir headed to the Delver’s Guild library and started researching the Banewarrens directly, although he turned up little of substance beyond what they had learned from Jevicca, Rehobath, and Lord Zavere.

Elestra, meanwhile, made a point of buying a newssheet. They were filled with news of the riots in Oldtown, and she found that Agnarr, Dominic, Tee, and Ranthir had been prominently credited with the quick and successful response to what was being described as a sorcerous attack on the city. She also discovered that a 2,000 gold piece reward had been offered for the spellcaster responsible.

Elestra also made a point of digging up older copies of the day’s newssheets, printed before the riots. From these she learned that Gidden Primus, a mage of mild repute, had been found dead the night before in his apartment in Oldtown. His chambers had been rimed with frost and Gidden himself had frozen to death.

Tee had gone straight up to her rooms to snatch some sleep before heading back up to Oldtown to perform her watch duties for the Brotherhood (it had been more than a day and a half since she’d woken up), but Elestra caught up with her in the common room when she came back down around 11 o’clock.

They agreed that there didn’t seem to be any connection between the death of Gidden Primus and the opening of the Banewarrens.

When Tee left, Elestra shapeshifted into a dog and accompanied her. Tee appreciated the company, and they thought it might be useful to have another pair of eyes and legs available if they were needed.

In fact, it turned out that they were needed sooner rather than later. As they passed through the streets of Oldtown, Tee spotted Iltumar sneaking his way back towards Midtown – his watch duties on the apartment complex must have just ended.

Tee warned Elestra and they easily avoided him. Once he had passed, Tee indicated that Elestra should follow him while she continued on to the apartment complex.

Elestra did. Or at least tried to. After a few blocks, Iltumar seemed to become suspicious of the “stray” that was dogging him. Elestra tried to throw his suspicion by acting innocently (sniffing at garbage piles and the like), but in the process she ended up losing him. Frustrated, she turned back and rejoined Tee at the apartment complex.

The rest of the evening passed quietly. When Tee’s shift ended at 6 o’clock they both headed back to the Ghostly Minstrel and managed to grab a few more hours of sleep before the new day began.

RETURNING TO PYTHONESS HOUSE

(09/16/790)

The mansion on Nibeck Street that Jevicca had identified as the origin point for the appearance of the surge of Tavan Zith’s wild magic was very close to Pythoness House. So close, in fact, that they feared there might be a connection. Could the cultists be responsible for the breaching of the Banewarrens?

“If we check it out and there’s nothing there,” Ranthir pointed out, “Then we’ve lost nothing. But if there is, then we may have saved ourselves considerable time.”

So before heading to Nibeck Street, they return to Pythoness House.

They found it undisturbed… until they reached the gatehouse. As Tee passed through the door of the narrow space, the ghostly specter who had assaulted them before suddenly rematerialized. At the same instant, the trapdoor slammed shut behind Tee, separating her from the others.

“Leave this place of evil before it consumes you!”

“Okay.”

“… what?”

“If you’ll just open the trapdoor, I’ll leave.”

“Very well.” The ghost waved and the trapdoor swung open.

Tee grabbed it and held it open. “There’s a ghost! Help!”

Ranthir called up from below, “Did we want to talk to it this time?”

Agnarr, who had leapt up the ladder and had his sword halfway out of his sheathe, stopped. “I suppose…” He sighed heavily.

The ghost, for his part, now seemed to be more flustered than sinister. They asked him his name and he introduced himself as Taunell.

“What are you doing here?” Elestra asked.

“I lived in this house two hundred years ago. I served as priest for the Kollotis merchant family. It was a minor house and its fortunes were waning. It must have appeared weak. One night a band of brigands assaulted the house. They killed most of the household and stole the family jewels. The Kollotis family never recovered. I, myself, found myself unable to leave this mortal plane. I had no greater desire than to see the family protected, and now I seek to protect this house against those who would stain their memory.”

“And the chaos cultists?” Tee asked.

“They came here five years ago. I am shamed to say that I could not make them leave this place.”

“Do you know anything about Wuntad?”

“He was their leader. Among the women who lived here I had a friend named Maquent. She told me that his ultimate goal was to join all the followers of chaos in a common cause. He brought great evil into this house.

Tee grimaced. “He left with it, too.”

“If we brought him back here, is there anything you could do to stop him?” Elestra asked.

Taunell lowered his head. “I couldn’t even stopped him when he lived here.”

“I understand,” said Tee. “It’s all right.”

Running the Campaign: Multi-Threaded Campaigns – Campaign Journal: Session 28C

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index