ADVENTURE OVERVIEW

Each adventure in Journeys Through the Radiant Citadel is built on a common template:

- Background

- Setting the Adventure

- Character Hooks

- Starting the Adventure

Followed by, of course, the adventure itself and then the accompanying setting gazetteer.

Setting the Adventure suggests three options where each adventure could be set. One is “Through the Radiant Citadel,” which, as noted, indicates where the Concord Jewel is located. Another suggests where this civilization could be slipped into the Forgotten Realms. And the third does the same for some other official D&D campaign setting, either Eberron, Greyhawk, or, in one case, Mystara.

Character Hooks are interesting. Each scenario ostensibly includes multiple hooks (usually three, sometimes only two). There’s some variation here, of course, across the many adventures, but these “hooks” are generally just reasons the characters might be visiting the region. For example:

- The characters are going to a local festival.

- The characters are visiting a friend.

- The characters are hired as guards by someone visiting the area.

In a few cases the “you’re in the area to do X’ can at least loosely qualify as a surprising scenario hook (because it has at least some proximity to the scenario premise), but mostly it’s just, “You’re traveling through Y, and then…”

So the “hooks” are then followed by Starting the Adventure, which is almost always a random encounter that informs the PCs of the scenario’s existence. This random encounter is what I, personally, would consider the actual scenario hook.

The intention of having multiple scenario hooks is great: It would theoretically make it easier for DMs to incorporate these adventures into their campaigns and/or make hooking the PCs into the scenario far more robust (because if one hook failed, there would be additional opportunities). But because the actual hook is the random encounter, this can, unfortunately, lead to very fragile hooks in actual practice. For example, in “The Fiend of Hollow Mine” the PCs need to:

- Not detect and decide to skip the bounty hunter ambush.

- Not chase the bounty hunters who are scripted to flee.

- Accept a random barkeep’s invitation to have a drink, rather than continuing on to their actual goal.

- Get approached by Paloma the Outlaw and decide NOT to capture her for the bounty they’ve just been informed she has on her head.

- Finally, accept the job offer from Paloma.

That sequence of events probably happens more often than not when running “Fiend,” but it’s A LOT of potential points of failure to navigate through before the adventure has technically even started.

One more decision I really don’t like in this book is that no clear credit is given to the writer of each adventure. This was done in both Tales from the Yawning Portal and Candlekeep Mysteries, and its absence from Journeys Through the Radiant Citadel feels particularly grody given how much of the marketing campaign for the book was, rightfully, focused on the phenomenal writing talent that made it possible. I should not have to use Google to figure out which author wrote which adventure, which is why I’ll be indicating authorship for each adventure below.

GAZETTEERS

Before we do that, however, let’s take a moment to consider the setting gazetteers that accompany each adventure. These include the usual list of locations (usually labeled on a map) and cultural information, but there are a few notable features I’d like to call special attention to.

Legends of X. This section presents a lovely blend of history and myth, while also typically grounding the setting into a unique fantasy metaphysic. It’s a nice way to neatly encapsulate the unique spin each setting gives to D&D.

Adventures in X, which gives four adventure seeds. These are pretty excellent throughout the entire book: They’re not generic ideas, instead being spiked with specific details that add value. Nor are they vague ideas. Too often I see seeds like this say stuff like, “There’s a weird glowing light, I wonder what it is?” In Radiant Citadel, the seeds reliably tell you exactly what that weird light is. Finally, the details provided generally give a clear direction for development.

Characters from X. If a player chooses to create a character from this civilization, this section includes three questions the DM can ask them to help ground the character into the specific context of the setting. For example, in Yeonido, these are:

- What is your social class and clan?

- Do you have a special role in the city’s hierarchy?

- How have gwishin [the ubiquitous ancestor spirits of the setting] affected you?

Each question is accompanied with a short guide and list of suggestions, perfect for guiding the conversation.

Names. Each gazetteer includes a list of sample names you can use for NPCs. I love having an NPC name list as a resource, and it’s particularly valuable here because the range of cultural inspiration drawn from for Journeys Through the Radiant Citadel is so diverse that literally everyone using this book will almost certainly find that some majority of the cultures detailed are exotic to them (and, therefore, more difficult to improvise appropriate names off-the-cuff).

The only shortcoming here is that it would be great if the sample name list was longer. (Which is why I actually expanded the lists in Journeys Through the Radiant Citadel: A List of Names.)

But this is actually the biggest shortcoming of the gazetteers in general: The practical realities of the book means that the really cool settings can only be sketched in with broad brush strokes. Sometimes this just means that you’re left hungry for more (a great problem to have), but in some cases the lack of detail can really cripple the settings and, in some cases, the adventures connected to them (a much less great problem to have).

For example, in the land of Godsbreath, the Proclaimers of the Covenant are charged by the gods to record the history of the Covenant’s chosen people.

Who are the Covenant?

They’re a pantheon which is “for you to define” (because I’ve hit my word count) “and might include gods appropriate to your campaign’s setting or deities unique to Godsbreath.”

… well, this is probably fine, because the gods are only <checks notes> the primary focus of the entire setting?

Oof.

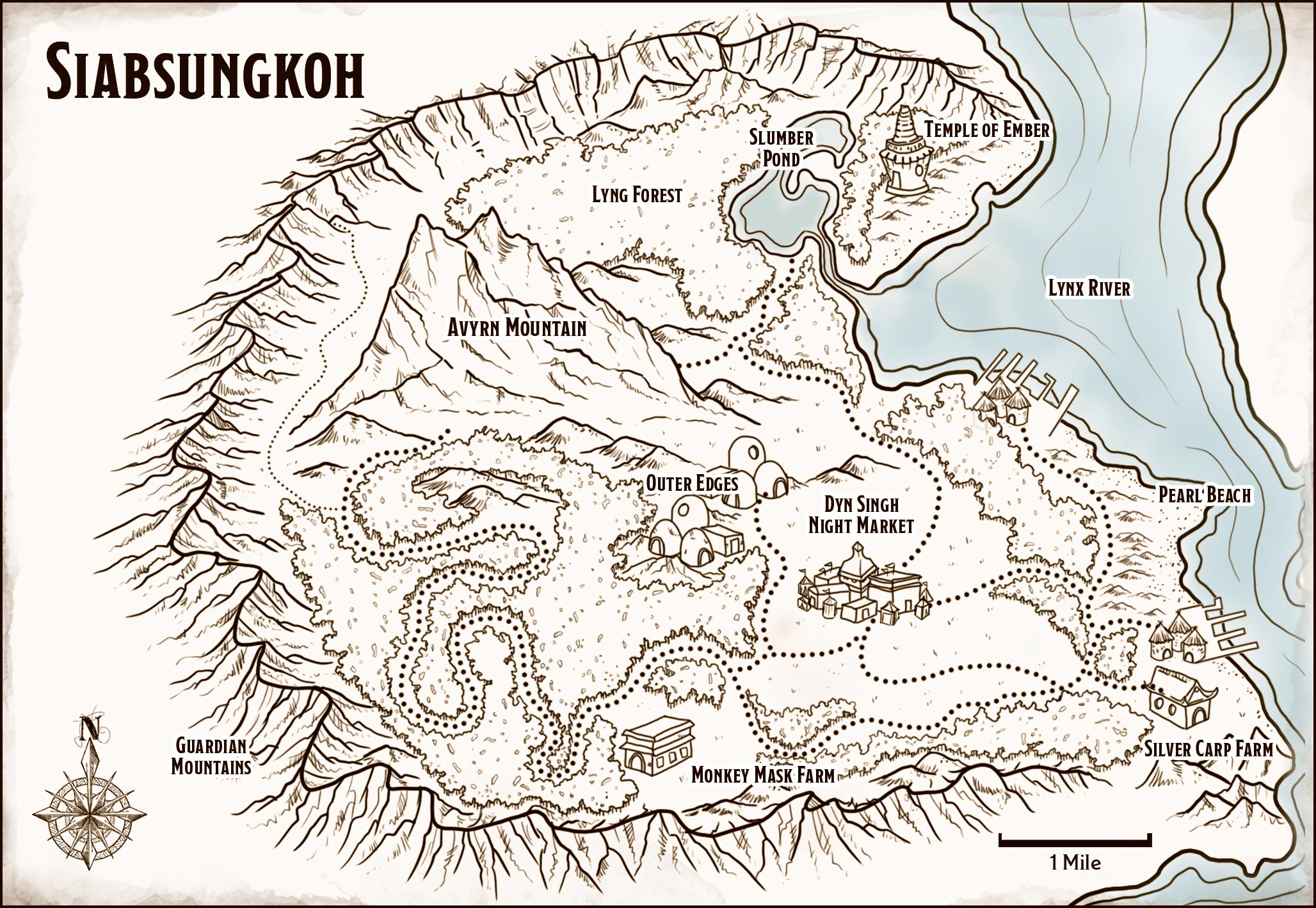

The lack of detail also spills over and creates a lack of scale. For example, consider this excerpt of text describing Siabsungkoh:

Traders from Siabsungkoh’s scattered communities flock nightly to the Dyn Singh Night Market, an ever-changing, town-sized market…

The [Outer Edges] that border the wilderness … are overgrown with lush greenery and lau-pop flowers. Many of the scattered communities here and across the valley reject the bureaucracy and crowds of the market district, braving the dangers of the nearby wilderness to stay self-sufficient.

And now compare it to this map of the region:

There are no “scattered communities” and the “Outer Edges” are, in fact, only a half mile from the Night Market itself, so (a) you can probably see one from the other and (b) there’s no room for multiple communities, let alone communities in separate “districts.”

Plus, the whole “civilization” is just a half dozen miles wide. A pattern which repeats throughout the book: “empires” that consist of a couple of towns; bustling “metropolises” with only a couple dozen buildings; and so forth.

So what happened here?

Well, based on my experience, I think it’s almost certain that the cartographer accurately (and evocatively) presented everything that was likely on the design sketch they were given to work from. But because there’s only room to present the setting in the broadest strokes, there just wasn’t enough detail on the design sketch.

Even without the scale that locks it in on the final version, barrenness on a map is interpreted as tininess.

What I do love about the Siabsungkoh map is the inclusion of locations NOT described in the limited text, including Monkey Mask Farm, Silver Carp Farm, and so forth. I’m a big believer in RPG maps inviting the user — including the DM — to explore the world. To ask, “What’s this?”

Is Monkey Mask Farm run by awakened monkeys?

Does it literally grow monkey masks on magically enhanced teak trees?

Do the farms of Siabsungkoh hang masks above their gate, representing the patron animal who protects their crops? (Are some of these masks possessed/enchanted?)

Tabula rasa is the scraped tablet. The empty spaces on the map. Those spaces can be fun to fill. But rasa is the fundamental flavor or essence of creation, and offering just a hint of it can often by even more powerful than the blank spaces.

So my bottom line on the setting gazetteers is this: What’s here seems consistently good-to-great. But issues with limited word count seem to consistently choke out their potential.

As a final note, I will suggest that the book could have done itself a lot of favors by presenting the setting gazetteers before each adventure, instead of after.

First, because the adventure comes first, the writers feel obligated to include a whole bunch of explanatory detail in the adventure that more logically belongs in the gazetteer (i.e., cultural information).

And then, second, many of the writers fall prey to the trap of using the limited space in their gazetteer to repeat descriptions of locations that are already amply detailed in the adventure itself. Yes, it’s easy to think, “This list of ‘Noteworthy Sites’ is supposed to include all the locations in the setting, so it logically must include all the places we visited in the adventure.” But, particularly when you’re fighting word count, this can really hurt the utility of your work.

If the gazetteers came first, both the temptation and necessity of repeating information would’ve been drastically reduced, freeing and encouraging the writers to pack more value into the book.