Go to Part 1

SALTED LEGACY (Surena Marie) is set in the Dyn Singh Night Market, an “endlessly changing maze of stalls filled with incredible wares, enticing smells, and magical lights” that I mentioned earlier in the review. It’s an adventure for 1st-level characters, and is designed for the PCs to level up twice (so that the next adventure in the book is for 3rd-level characters).

There are two core concepts in “Salted Legacy.” First, the PCs will compete in a series of market games as part of a festival. Second, they’ll be asked to investigate a series of attacks aimed to sabotage local businesses. The scenario’s primary problem is that it’s structurally swapped the primacy of these two concepts.

Let’s start with the sabotage plot: Kasem Aroon and his twin borther Vi Aroon operate the Spice Brothers stall in the Night Market. Vi, however, is getting married and moving away. Kasem realizes he can’t run the stall by himself, so he concocts a “brilliant” plan! He’ll sabotage the other businesses in the Night Market so that one of them will sell their stall to him. That way he’ll own TWO businesses he can’t run by himself!

So, obviously, this entire premise doesn’t make any sense. (I’d suggest setting things up so that Vi getting married means that Kasem, as the younger son, will be pushed out of the Spice Brothers. Kasem’s plan to acquire another a business, therefore, would make sense. There’s even some evidence this may have been the original ending of the adventure, as the published conclusion includes the option for a happy ending in which Kasem gets adopted into another vendor’s family… which obviously only makes sense as a “solution” if Kasem was not, in fact, going to own the Spice Brothers stall.) But that’s not actually the primary problem.

Structurally, the PCs witness a feud between two of the oldest and most respected families in Night Market, which Kasem has enflamed by using wynlings, winged feys he’s bribing with persimmons, to frame each owner for sabotaging the others’ stall. Both stall owners hire the PCs to get proof that the other family is responsible for all the sabotage!

The double-hire is a clever twist on the hook, but then the PCs start investigating and the adventure says (paraphrasing): “Literally nothing they do works. Your job as the DM is to make sure they cannot solve this mystery. Investigation checks? Nothing. Questioning? Nope. Stake out? Absolutely not!”

The stonewalling is necessary because the ultimate goal is to force the PCs to participate in the Market Games: No one trusts outsiders (er… except the two highly respected families who hired the PCs), so the PCs need to earn their respect by competing in the games. The more respect they earn, the more information they can get.

The “need” to block all lines of investigation leads to all kinds of silliness. For example, the PCs may find persimmon peels at the sabotage sites (from the wynlings). Logically, they should be able to find out who’s selling persimmons and maybe learn that Kasem has suddenly started buying a lot more than usual.

But that’s not allowed, so: “A character who further investigates these fruit peels learns no stalls in the night market currently sell persimmons.”

Ironically, this will likely lead players to hyper-obsess on these persimmons: If they aren’t sold here and nobody eats them, where are they coming from?! (This is never actually answered.)

Anyway, the point here is that the adventure is framed to make the mystery the players’ primary goal, but the mystery is not actually the focus of the adventure: It’s the Market Games. The mystery is just the mechanism used to force the PCs to play the games.

It would make a lot more sense to just have an adventure premise that says “play in the Market Games,” rather than “do this other thing, but I’m going to arbitrarily stop you from doing it until you play in the Market Games.”

Partly because I hate mysteries designed to prevent eh PCs from solving them.

Mostly because it turns the Market Games into a chore that the PCs have to complete. And chores are not fun.

Which is a pity, because once we actually focus on the Market Games, they’re a lot of fun! My personal favorite is the cooking competition:

MC: Welcome to Iron Chef Dyn Singh!

PCs: Awesome!

MC: Your secret ingredient is… SHRIMP!

PCs: Cool, cool…

MC: Giant shrimp.

PCs: Hol’ up.

MC: You will need to kill it first.

PCs: oh shit

“Salted Legacy” is a delicious treat that has been wrapped in unnecessary frustration. But what I want to emphasize is that there’s a pretty solid core here that can make for a fun evening with your group: The Market Games are fun. The cast of characters in the mystery story is memorable and well-drawn.

All you really need to do to tease out these flavors is (a) refocus the hook on the Market Games, (b) have the investigation pop up as a B-plot, and (c) default to yes whenever the players investigate something.

For the scenario hook, you might do something like:

- The PCs have been selected as competition ambassadors, and have been sent to the Night Market specifically to compete; or

- There’s a prize for this year’s competition which [thing they want/need].

But since this is also likely the first adventure in your campaign, you could also just tell your players as part of character creation to explain why they’ve all decided to compete in the Market Games this year and use it as the This How You Met framing story for the group.

If you wanted to prepare a revelation list ahead of time, the two key revelations I’d focus on would be:

- Persimmons are associated with the mischief sites. (And you can then trace the persimmons to Kasem.)

- There’s some sort of invisible, flying blue monkeys. (And then you can catch and interrogate them or follow them to Kasem.)

Ironically, you can do this pretty easily by just reading through the adventure and, everywhere it says “if the PCs do X, they don’t find anything,” simply replace it with “if the PCs do X, they find [useful information].”

Run as written, I would give this adventure a C grade. Since such minimal effort would probably polish it up into a B or B+ at the actual table, I think I’ll reflect its true value with a C+.

Grade: C+

WRITTEN IN BLOOD (Erin Roberts) is an adventure so good I’d give my left arm to run it.

A local curse/haunting in the land of Godsbreath causes the hands of those who drown in the lake to come back  as undead crawling claws. When enough of these horrors gather in one place, they form an amalgam entity called a soul shaker.

as undead crawling claws. When enough of these horrors gather in one place, they form an amalgam entity called a soul shaker.

Like a rat-king, but much, much worse.

“Written in Blood” begins with the PCs heading to Godsbreath for a festival.

… wasn’t there a festival in the last adventure, too?

There was. And there will be in the next adventure and the adventure after that and several more. Honestly, your PCs are going to look back at Tier 1 and remember absolutely nothing, because they spent the whole time stoned out of their minds.

This particular festival is the Festival of Awakening. Its unique calling card is the Awakening Song, a huge oral tradition which records the entire history of Godsbreath. Proclaimers circle through the festival singing sections of the Song, with the crowd intermittently picking up favorite verses and singing along. Later, a Proclaimer will ask to accompany the PCs, believing they are caught up in important events and that their deeds should be woven into the Song’s ever-evolving form.

This is a great example of the rich texture Roberts weaves into the Godsbreath setting, and the quiet brilliance she displays in weaving that detail into the action of the adventure.

In fact, the only real drawback of “Written in Blood” is that it’s a prime example of limited word count hamstringing development. For example, “characters who spend an hour exploring the festival [listening to the Song] learn much about the history of the land.” But you can’t actually share that with the players.

If you really want to make this adventure sing (pun intended), then you’ll want to bear a wary eye for stuff that’s often literally begging you to flesh it out and seize the opportunity to do so before running this one.

And you’ll definitely want to run this one, because it’s a goddamn creepfest that will put your players on the edge of their seats and then rip their hearts out.

We begin with the land of Godsbreath itself, which is presented in a gazetteer which is simply exceptional (and probably the best one in the book).

The fertile lands of the region are deteriorating, forcing more and more farmers to migrate from the rich lands of the Ribbon into the Rattle, a fertile, but extremely dangerous region.

That, all by itself, is a brilliant premise for endless adventure.

And then Roberts drops this bomb:

Most people in Godsbreath worship one or more of the Covenant gods, who worked together to bring the first folk to this new land. Over long generations since, these deities have stood united as the guardians of Godsbreath. But of late, they have begun to work independently to recruit and reward their own followers.

Through recent prophecies known only to themselves, the members of the Covenant have learned the blood of a deity is needed to revitalize the soil of the Ribbon and stave off potential famine across Godsbreath. In response, the gods are becoming more active, shoring up their power to avoid becoming this necessary sacrifice.

The tension between the Ribbon and Rattle was already incredibly well done.

But to add this to it?

Competing plots of deicide. A religion dedicated to transmitting truth fracturing on its own secrets. A covenant of gods forced to betray one of their own.

It’s simply inspired. Adventure just boils out of it.

All right, so we have the cursed and dying Ribbon that’s forcing people into the strange and dangerous frontier of the Rattle. This is the essence of gothic horror, infused into both the darkest and most hopeful aspects of the modern Africa diaspora, then draped with the most disturbing visions of West African magical realism. It’s redolent with possibility.

And Roberts delivers. The adventure drips with the dry dust of the Ribbon and the eery edge of the Rattle.

Atmosphere is good, but the real meat of “Written in Blood” is the human story at its heart: Of a young girl who lost her friend to the crawling claws and the dark waters of the lake… and now her friend has come back.

When the PCs discover this truth — and the girl — crouching in the dark, everything comes together: The place. The imagery. The characters.

I don’t know what your players’ (or their characters’) reaction will be to this truth.

And that’s the beauty of it.

The terrible beauty.

Grade: A

THE FIEND OF HOLLOW MINE (Mario Ortegón) continues the transplanar pub crawl, with the PCs heading to the city of San Citlán to “enjoy the food, parades, and celebrations of the Night of the Remembered” festival.

I’ve seen some reactions and reviews to Journeys Through the Radiant Citadel express frustration that the specific cultural inspirations aren’t listed for each civilization/adventure. I understand this impulse, but I think it misses the point.

There are certainly cases where it might make it easier for me to, for example, do additional research on fashion so that I can make my NPC descriptions richer. But one of the things I really enjoy about Radiant Citadel is that it’s NOT “here’s fantasy Ethiopia with new labels that we can trademark,” which is a trap I’ve frequently seen projects like this fall into. Radiant Citadel’s authors are being truly inspired by their source material, using it to create something new and unique to their vision, and then blending it with the vast mythos of D&D.

So “Fiend of Hollow Mine,” for example, has clear Mexican inspirations. But there’s also a Mesopotamian-by-way-of-D&D demon lord. And Ortegón takes the Day of the Dead and interprets it through the metaphysics of D&D to create the Night of the Remembered, where the souls of the dead literally manifest.

And then he takes it one step further and asks, “But what would happen if a soul doesn’t cross over at its appointed time?”

The answer is: Simply persist.

And so San Citlán is studded with friendly undead. People who just… kept on “living” when death should have come instead. The olvidados are literally those “forgotten by death.” The result is such a cool and unique place that my only quibble is that, once again, I would have loved to see it fleshed out more.

(Pun intended.)

Okay, so the PCs are heading to San Citlán. They discover that there’s a deadly plague called sereno afflicting the region.

There are a couple of things I really love about sereno. First, it literally spreads via a “cursed wind” that blows at night. Germ theory is great, but in a fantastical land, I love diseases that are fantastical in nature.

Second, sunlight alleviates the illness. And, indeed, it can only be magically cured and only if the spell is cast in sunlight. This is mechanically simple, but gives a distinct and evocative flavor. It also makes the disease relevant to the PCs in a clever way: Although it doesn’t really factor into the adventure, you can imagine PCs contracting this disease deep in a dark dungeon or the Underdark and being unable to cure it (only triage it) until they can return to the surface.

The basic concept of the adventure is that, a generation ago, a warlock named Orencio was caught and executed. Before he died, however, he’d made a deal with the demon lord Pazuzu, trading the soul of his son for great power.

Orencio thought he’d pulled a fast one, but what he didn’t know is that his girlfriend (who was also the one who turned him into the authorities) was pregnant. Their son, Serapio, is approaching his twentieth birthday and, under Pazuzu’s influence, is turning into a tlacatecolo — an owl-demon which spreads pestilence. (In this case, sereno.)

The PCs are pointed in Serapio’s direction by a freedom fighter. Following his trail, they hopefully learn the truth of what’s happening to him and, eventually, bring him to bay.

The biggest problem with “The Fiend of Hollow Mine” is that it’s incredibly fragile. There is a very long sequence of hoops that the PCs need to jump through. Some of these hoops are surprisingly difficult to get through (although Ortegón usually provides some mechanism for the PCs to just keep making skill checks until they finally roll high enough). Other hoops are hidden, which is… fun.

There are a couple of saving graces, however.

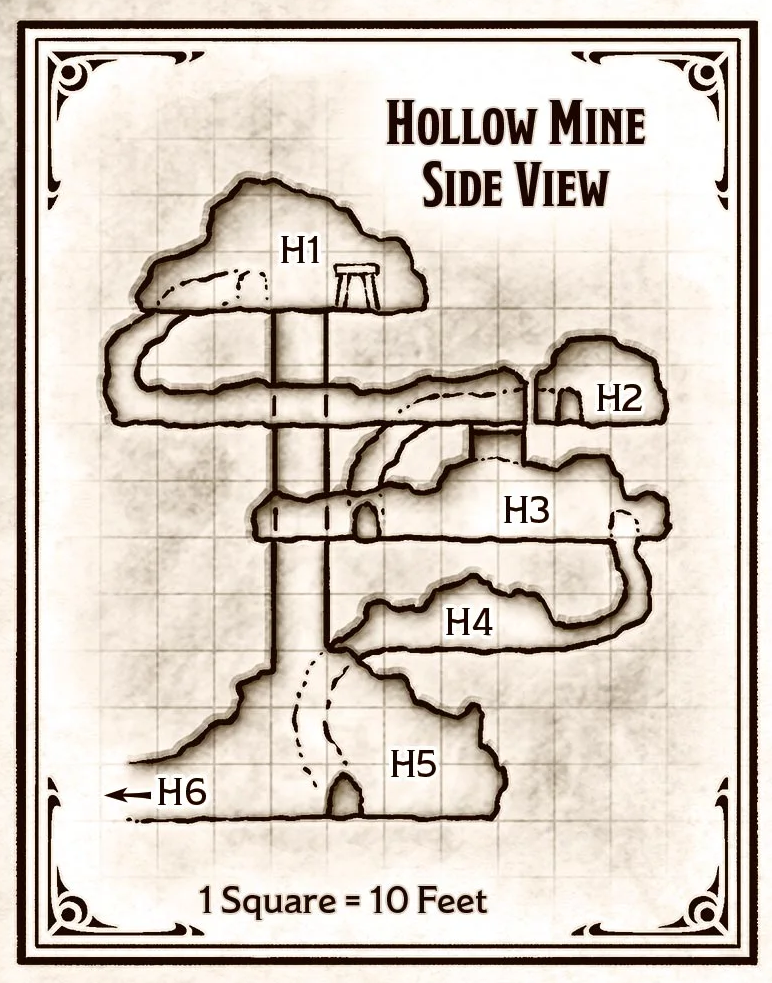

First, the middle chunk of the adventure takes place in the small dungeon of Hollow Mine. The map design here is excellent:

For a small dungeon, this is deliciously xandered. And the key is equally good, with vivid imagery and meaty detail.

The second saving grace is the conclusion of the adventure. Ortegón does a great job framing it so that the PCs will have to decide whether to try to bring Serapio in quietly so that his curse can be removed, or simply kill the corrupted soul.

Grade: C+

Go to Part 4