You can be absolutely terrified and still live to scream another day. Ennie Award-winning and USA Today Bestselling Author Justin Alexander breaks down the four Pillars of Horror, along with the shortcuts and multipliers that will make running a horror adventure in D&D or any other tabletop RPG frighteningly simple!

Advanced Gamemastery: How to Run Horror RPGs

The Vladaam Affair – Part 16E: Slave Trade Handouts

BUSINESS OF THE VLADAAM SLAVE WAREHOUSE

This collection of posted bills records recent sales and transfers of inventory through the lower warehouse. A sampling of entries include items such as:

- Elven maid, 78 years of age, permanently dominated to any compliance

- Four dwarf workers, dim-witted but strong in thew

- Female child, of island stock

- Boy of sixteen, tongue removed, docile

Most of these slaves are being shipped to an “Ennin slave market” which is apparently located in the Undercity “beneath Delver’s Square” (the slaves are being transported via the sewers). Slaves are also being shipped to three “curse dens” located around the city:

- Curse Den – Guildsman District – Nethar Street

- Curse Den – Oldtown – Yarrow Street

- Curse Den – Rivergate – Outer Ring Row

In addition to slaves, large shipments of something referred to as “liquid pain” are also being shipped to the curse dens from here.

One particular reference of note identifies a batch of slaves as being “held at the behest of the Pactlords”. Another says that a slave is to be sent “directly to Tridam Island by command of the Pactlord”.

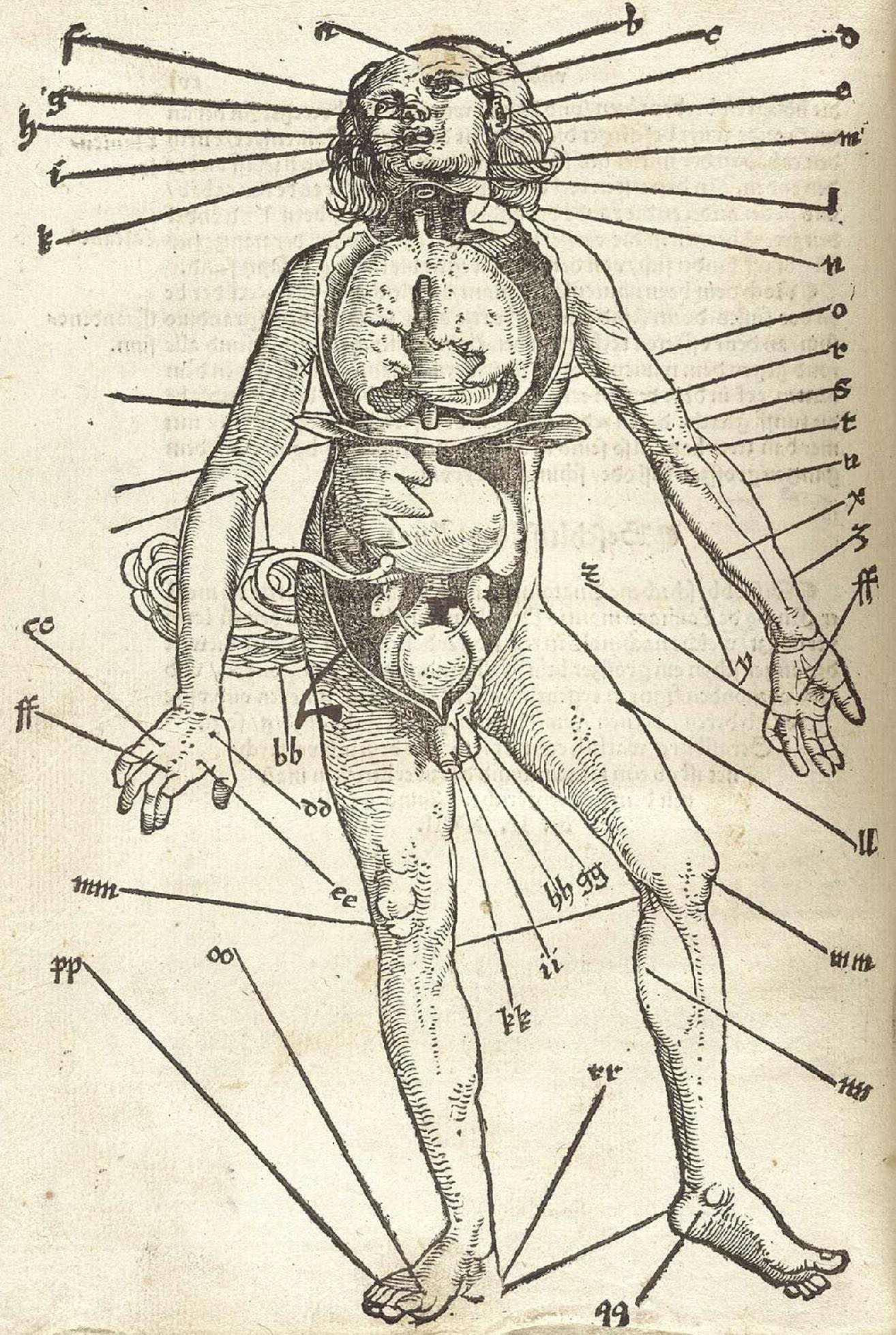

INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE APPARATUS OF LIQUID PAIN

Detailed anatomical diagrams and accompanying texts explicate the points on the human body to which various tubes, syringes, and metallic attachments are to be placed (while others are stimulated through the use of acupuncture needles, including several needles placed into the optic nerves). The goal is to create “overlapping resonances of agony”, serving as the raw catalyst for withdrawing a substance referred to as “liquid pain” or “agony”.

The full process requires the use of a complicated apparatus capable of generating a “sympathetic resonance” which can be contained within glass cylinders crafted with exact precision.

In addition, the properties of the resulting “liquid pain” are detailed, along with alchemical instructions for how it can be purified and “stabilized”.

AGONY: Also known as “liquid pain”, this thick, reddish liquid is the distilled essence of pain, captured using special spells or items. It is highly sought after by outsiders. Through an alchemical law of antagonism it creates a feeling of intense pleasure in addition to its other effects. Recreational users use small, ceremonial knives to cut themselves and deliver the drug.

A MISSIVE REGARDING SLAVES

Guildmaster Arzan tells me you have a sharp eye. I expect you to practice it now. We are conducting crucial experiments in the apartments on Crossing Street and are in need of experimental stock. We are particularly in need of those with an affinity for metamorphic compounds while also possessing the physical endurance to withstand the experimental techniques. If you observe any such during your service, flag them to my attention immediately.

LETTER TO GUILDMASTER ARZAN

To Arzan, the most illustrious Guildmaster of the Red Company of Magi—

I have recently had an item of most potent power pass into my possession.

While slipping through the Teeth of Light after sailing north towards Trollone, we were blown off course by a strange tempest of silver and black which first seemed to roil the waters beneath us before emerging – or, perhaps more accurately, whipping forth – in what could only be described as a violent evaporation.

I was not certain that the Sarathyn’s Sail would survive the strange gales which ensued, nor the strange manifestations which occurred therein. As for those of my crew who simply vanished during the storm… I pray that they were merely swept into the sea and met their fates in a watery grave, for the alternative is too disturbing to contemplate.

When the storm finally released us from its grasp, we were in ill condition. Fortunately, we found ourselves near a small island with a hospitable cove. We were able to limp our way into this and begin effecting repairs.

While these efforts were under way, I led a small band of men into the island’s interior in search of a fresh water well or spring from which we could resupply. Instead, we stumbled upon a set of cyclopean ruins. These were marked by a great number of carvings, bas reliefs, and statues depicting serpents and, within the deeper recesses of the complex, serpent-headed men.

With dusk closing about us, we returned to the ship, but I vowed to return the next day and continue our explorations. It was at this juncture that the first of my men disappeared. At the time we thought it simply misadventure, but subsequent events would prove this not to be the case.

Returning to the ruins the next day, however, we pushed further into the lower chambers. Within one of these chambers I discovered, among other treasures, a curious ring in the the shape of twin serpents, one of mithril and other of taurum, swallowing each others’ tails. We have been able to ascertain that not only is the ring itself magical, but that it has been constructed to contain some even greater magical enchantment. It is for this reason that I am sending it into your care, in the hopes that perhaps your Red Magi might be able to unlock its secrets.

As for the ruins themselves, it emerged that the serpent-men who had constructed them had not entirely abandoned them. Instead, they appear to have withdrawn into caverns even deeper beneath the island. I suspect that they return to the upper caverns only as a kind of holy pilgrimage. As for what other secrets or lost lore they might be concealing, or what cataclysm precipitated their withdrawal from the sunlit world, I can only speculate.

Yours sincerely,

Captain Crotika

LETTER FROM THE FOUNDER’S GUILD TO CAPTAIN MORSUL

Captain Morsul—

Please accept this hellsbreath rifle, so recently liberated from the Shuul, as a token of good faith from the Founder’s Guild.

You will find it to be a powerful and potent weapon, but extremely dangerous if carelessly used. When priming the gunpowder pump, great care must be taken not to over-pressurize the reservoir of alchemist’s fire. If the reservoir becomes over-pressurized there is a great risk of a back-blast being triggered which can destroy the weapon entirely (and cause great harm to the one wielding it).

Similar caution should also be used when refilling the reservoir, as there can be great risk in the moments during which the alchemist’s fire is exposed to raw air.

Master Astrek

Red Company of Founders

Brass Street

Ex-RPGNet Review: A Lion in the Ropes

Stephen Chenault designs a solid D20 module, Troll Lord’s first. Although possessed of great strengths, A Lion in the Ropes is held back by a central weakness in its design.

Review Originally Published May 21st, 2001

Warning: This review will contain spoilers for A Lion in the Ropes. Players who may find themselves playing in this adventure should not read beyond this point.

At first glance, A Lion in the Ropes is a fairly typical D&D module: PCs enter a village, the village is besieged by “something evil,” and the PCs take the necessary steps to rid the village of evil. But there are a couple of things which set it apart from its familiar brethren:

First, as with Troll Lord’s other products, A Lion in the Ropes is distinguished by its distinctive and developed setting. The village which the PCs enter is not just Generic Village #117, it is Capendu – a place given a specific history, context, and character. Some of this is accomplished through little details which make all the difference (for example, the fact that the roofs in Capendu are made of a distinctive green tile which comes from a nearby town). In other cases, it is accomplished through elements more integral to the adventure. For example, a central element in the adventure is the Church of the Four Saints. The church was built upon the ruins of a prison. In most adventures such a prison would simply be “ruined” – in the case of A Lion in the Ropes, however, the prison was specifically torn apart by the citizens in order to build the town… which is why Capendu’s structures are built of stone (unlike the other towns in the region).

Although designed for Troll Lord’s After Winter Dark campaign setting, I find that the setting elements they include in their adventures are of a quality which not only allow them to be easily incorporated into any generic fantasy world, but will enhance the world into which they are so included.

Stephen Chenault (the author) also does a nice job of interweaving multiple actions into his narrative: A lion who is mistaken for a demon, a group of undead who are actually responsible for terrorizing the town, and a band of bandits who attempts to take advantage of the chaos surrounding the murders committed by the undead. By interweaving this three-tiered dynamic into the complex supporting cast established in Capendu, Chenault manages to create a fairly compelling low level adventure.

Chenault also does a nice job of making sure that, if the PCs have an deficiencies in their skills or resources while tackling the task he’s set them, that there are ways of filling those deficiencies within the course of the adventure. At the same time, however, Chenault makes sure that there are contingencies which will allow the DM to take away the PCs’ new toys if he feels they will be overly powerful beyond the scope of the adventure.

Another point of commendation in the module’s favor is the boxed text. Although, at times, the text makes decisions for the PCs (a common mistake by module writers, but one which drives me right up the wall because it means I absolutely cannot trust the boxed text while running the adventure), it is also written very strongly – and, therefore, worth salvaging.

WEAKNESSES

Unfortunately, not everything about A Lion in the Ropes is equally commendable. The most significant, and perhaps crippling, problem is actually hinted at in Chenault’s own words:

“This mystery revolves around three separate actors. The Orinsu, the escaped lion, and the bandit, Orange-Hair. To track the movements of all three, the Referee should create a time line and allow the characters to weave in and out of it in a chaotic, albeit, realistic manner.”

Wait a minute. The referee should create a time line? If Chenault feels that the successful running of this adventure requires a time line to be established, why doesn’t he provide one?

And that pretty much sums up the source of most of my problems with this adventure: At many points it reads less like it has been designed, and more as if it had been merely outlined. To a certain extent, I feel as if Chenault became trapped by the standard concept of what “a module must be like” – and couldn’t get his ideas to function sufficiently within those constraints. A Lion in the Ropes might have risen above being merely good to something truly memorable if Chenault had followed his instincts and designed the adventure primarily around a time line of events – preferably a branching one which showed some responsiveness to multiple courses of action taken by the PCs, with specific events along each branch of the time line detailed.

CONCLUSION

That being said, A Lion in the Ropes is a solid module. If you’re looking for a memorable locale, a mystery, and undead for your low level party (the module is designed for levels 2-4), this is probably a good place to look.

Style: 3

Substance: 3

Author: Stephen Chenault

Company: Troll Lord Games

Line: D20

Price: $6.00

ISBN: 0-9702397-5-0

Production Code: TLG1401

Pages: 24

There was an ineffable quality to Troll Lord’s first modules that I really struggled to communicate in my reviews. There was, for lack of a better word, a texture to them that made them feel woven into a deeper reality. There was something magical about them that I desperately wanted to bottle up and bring to the table. But they also, as this review alludes, often had some deep issues that would have required some significant labor to polish them up and actually run them to best effect.

As a result, very few of these modules ever made it to my table. I sometimes wish that I’d run more of them. Perhaps some day I shall.

Many of these modules, including A Lion in the Ropes, have been updated several times to new editions. I haven’t checked out any of these revisions, so I can’t really comment on whether any significant changes have been made to their content or presentation. This review is strictly of the original D20 System edition.

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.

Ptolus: Running the Campaign – Contract Handouts

DISCUSSING

In the Shadow of the Spire – Session 48A: A Night in the Necropolis

Standing outside the door were a young man with his brown hair pulled back in a ponytail and a lithe woman with black hair down past her shoulders. The young man stretched out his hand, “My name’s Marcus Hunter. We’re looking for Tithenmamiwen. We have business from the Delver’s Guild.”

Agnarr slammed the door in their face and went back to polishing his sword.

I love a good prop.

They’re immersive, riveting, persistent, and just plain fun for the players.

There are all kinds of props, of course, but among the best are interactive ones. There’s just something deeply powerful about the players physically interacting with something that their characters are also physically interacting with.

For similar reasons, although props are great as a vector of information (and that’s certainly the primary function for most of the props I create), it’s fantastic when a prop is something that the characters can actually use. Something they can get proactive with, not just react to.

And this is why I love writing up legal contracts as props.

First, getting them to sign the contract as their characters gives you that awesome immersive hit. (One of my players has the signed copy of the Hunter contract safely stowed amongst their notes.)

But the contract is also a legal instrument. It’s more likely than not that the PCs will be able to use that contract to further their agenda: Protecting themselves from someone trying to take advantage of them, or leveraging the terms of the contract to force the outcome they want.

(Or, alternatively, an NPC using the contract against them. Which is almost as good.)

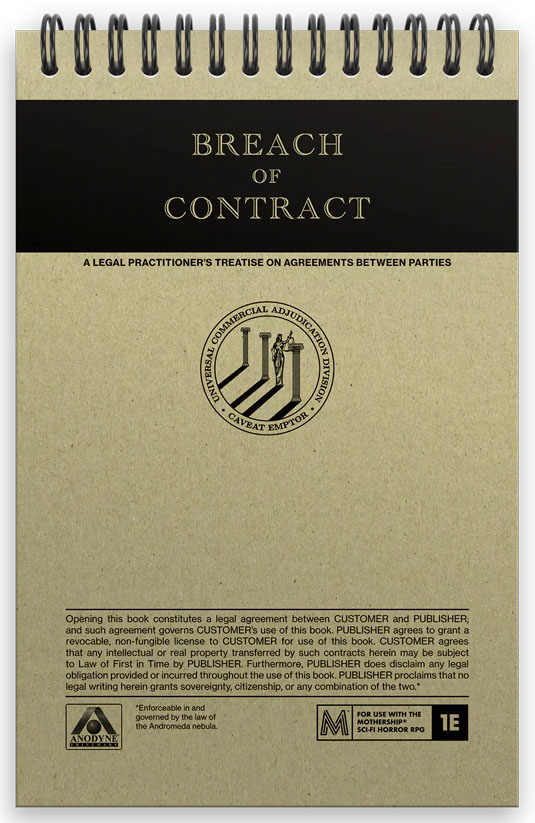

There’s a really cool supplement for Mothership called Breach of Contract, which is just a full book of tear-out form contracts that you and your players can fill out. For obvious reasons, I’m looking forward to figuring out how to integrate these into my Mothership open table.

If you’re looking to create your own contract handouts, I recommend googling real world contracts — particularly seeking out historical examples if that’s your milieu — and then stripping them down to the bare essentials. Borrow overall structure and key turns of phrase for flavor, but I don’t think it’s necessary to waste a lot of time customizing a 30-page pseudo-legal document, even if that’s technically what should be signed. (Think of producing something closer to a memorandum of understanding, if this bugs you. But, generally speaking, anything longer than a page is probably overkill.)

Don’t be afraid of letting the PCs renegotiate the terms of the contract. That might involve just crossing out and rewriting terms on the physical handout, or you may need to make some digital revisions and print up a new copy. Whatever works.

Campaign Journal: Session 48B – Running the Campaign: Laying Groundwork

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index

In the Shadow of the Spire – Session 48A: A Night in the Necropolis

SESSION 48A: A NIGHT IN THE NECROPOLIS

January 9th, 2010

The 26th Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

They cleaned the hall and moved the corpse into Ranthir’s make-shift laboratory. By the time Elestra was ready to force answers out of the drakken, they had carefully hashed out two questions to ask her and decided that they would confer on the third depending on the answers they received on the first two.

As Elestra animated the corpse, it jerked into a sitting position. The drakken’s head snapped back, audibly breaking her neck. Her words gurgled jaggedly in her throat.

“What was your mission?”

“To retrieve the askara research materials and kill the elf.”

(“Kill the elf?!” Tee demanded. “Why the elf?!”)

“Where were you supposed to report back to?”

“The Temple of Deep Chaos.”

“Where can we find Wuntad?”

“In the Haven of Gisszaggat.”

Black blood burst from her mouth and the body collapsed.

REVENGE SERVED IN FIRE

“That’s right,” Tee said. “We took all their research. All of that work for nothing.” She thought about it for a moment. “Do we actually need that research? Couldn’t we just burn it and make sure they never got it back?”

“I’d rather not… burn it,” Ranthir said, with a slightly strangled tone to his voice.

After conferring they decided that what they could do was to have Ranthir make a duplicate of the research and then destroy the original in a way that would make the cultists think that it no longer existed.

“We’ll send them burned scraps of it,” Tee said. “Or, better yet, I can cut out pieces of it and use it to write a message to Arveth.”

“This might be why they want to kill you,” Elestra said.

“Probably,” Tee said. “But I’ll make my own death.”

During the night Ranthir, sustained by a magical ring, had been able to continue his studies for several more hours. He spent that time studying the crystalline armor, concluding that – although it was derived from similar technomantic arts – it was not actually chaositech, nor did it bear the taint of such items. It would be safe to use.

Knowing that it was safe, Tor was more than happy to take the miraculously endurant armor. It would make an admirable replacement for his breastplate.

Shortly thereafter, the construction crew showed up for the last morning of their work on the suite. Tee quickly shuffled the body into her bag of holding (“for later disposal”).

They retired to Tor’s room. Tee had Ranthir immediately copy a few of the sheets from the askara research, then she took them, scorched them, and cut out semi-burned letters and words to form a message:

I’m still alive and loving the armor.

Love, The Elf.

THE HUNTER PARTY

Tee returned to the others. While they were gathering up their gear for the day, there came a knock at the door. They exchanged looks. None of them were expecting company.

Agnarr got up to answer it. Standing outside were a young man with his brown hair pulled back in a ponytail and a lithe woman with black hair down past her shoulders. The young man stretched out his hand, “My name’s Marcus Hunter. We’re looking for Tithenmamiwen. We have business from the Delver’s Guild.”

Agnarr slammed the door in their face and went back to polishing his sword.

With a sigh and perhaps a bit of a laugh, Tee went to the door and opened it again. Marcus introduced himself again and the woman as his sister, Talia Hunter.

Agnarr, with a bad feeling about all of this in his ornery gut, brusquely pushed past them and headed downstairs.

Tee invited them into the room and the others sat down with them around a table.

After proper introductions had been made, Marcus launched into his story. “My sister and I are members of the Delvers’ Guild. Our father, Adatol Hunter, was a member, too.”

Before Adatol had died, Marcus explained, he had found references to and descriptions of a specific section of Ghul’s Labyrinth and the passwords for the bluesteel doors leading there. He had spent the last years of his life dreaming of the treasures he would find if he could only find the places described.

The only problem? The records he had found referred to the “Laboratory of the Beast.” Without knowing where the laboratory was located, he couldn’t follow the instructions. But the research he had performed in trying to track it down included a reference to the Laboratory being used as a place to store the “Drill of the Banewarrens”.

It wasn’t hard to see where this was going: When Tee had started shopping the drill around, it had come to the attention of the Hunters and they had begun inquiries. They knew that the Laboratory of the Beast must lay beyond the Greyson House complex that the group had claimed a guild monopoly on exploring.

“We had papers drawn up with the guild allowing us to exploit your monopoly in exchange for a ten percent return.” Marcus presented them with a contract.

Ranthir tried to weedle the passwords or their maps out of them, but they politely refused.

“Are you planning to go down there by yourselves?” Tor asked.

“No,” Talia said. “We’ll be hiring a full expedition.”

The party tried to offer a reverse deal: They’d do the delving if the Hunters gave them the information they had, and in exchange the Hunters would get a cut without taking any risk on themselves. The Hunters, however, were adamant: They wanted to do it to honor their father’s legacy. And they wanted the challenge for themselves.

(“Besides,” Tor said. “When would we have time for that?”)

They asked the Hunters to wait downstairs while they discussed the matter. The Hunters agreed and excused themselves.

The debate focused around the Hunters themselves: Could they be trusted? How did they know they weren’t somehow in league with the cultists? Or the Surgeon in the Shadows?

“Is it even safe for them to be down there?” Elestra asked.

“They’re delvers,” Tee pointed out. “They’re going to be go delving somewhere.”

Eventually they decided to sign the contract, but with a few additional provisos: First, they wanted the Hunters to leave the goblin clan alone. Second, they wanted first pick of any material relating to the Dreaming Arts. Third, they wanted full access to any lore the Hunters retrieved from the depths. Fourth, when the Hunter expedition was completed, they wanted to know the passwords they had used to bypass the bluesteel doors.

When they fetched the Hunters back up for more negotiations, the Hunters agreed to their terms with the proviso that they would trade knowledge for knowledge: In exchange for the maps from their expedition and the password for the bluesteel door, they wanted a copy of the maps that Ranthir and Dominic had made while exploring the Laboratory. This was readily agreed to, and Ranthir began making a copy of their maps… and when the first (while perfectly functional and accurate) proved not to be elegant enough, he scrapped it and began anew (this time executing a proper work of art).

While he worked, Ranthir made a point of asking the Hunters about putting the passwords in trust. (“Just in case you don’t come back…”) The Hunters said that they would be filing an expedition plan with the Delvers’ Guild which would include that information. “We’re also purchasing retrieval insurance through the Guild,” Talia explained.

The contract was properly amended and signatures were placed on both copies (one for the party and the other to be filed with the Delvers’ Guild showing the Hunters’ right to exploit their monopoly).

Running the Campaign: Contract Handouts – Campaign Journal: Session 48B

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index

Archives

Recent Posts

- Games Unplugged Review – Lejendary Adventures: Beasts of Lejend – Cyclopedia of Creatures

- Campaign Status Module: Trinity Toolbox

- Video Review: Brindlewood Bay

- Bonus Videos! – Mothership & Crooked Moon

- Games Unplugged Review: Heavy Gear – Tactical Space Support: Space Warfare

Recent Comments

- on Dungeons: Player Mapping

- on Dragon Heist Remix – Part 3: Faction Outposts

- on Ex-RPGNet Review: The Speaker in Dreams

- on Roleplaying Games vs. Storytelling Games

- on Storm King’s Remix – Part 4: Hekaton is Missing!

- on How to Prep – The Haunting of Ypsilon-14

- on Whither the Dungeon? – The Decline and Fall of D&D Adventures

- on D&D 5E 2024 – Why Rules Glossaries Kinda Suck

- on Dissociated Mechanics – A Brief Primer

- on Dragon Heist Remix – Part 4D: Xanathar’s Lair