Recently I’ve posted a few ultra-short scenarios that I’m referring to as quick shots. (You’ll find links to them down below.) I’ve had a few people express confusion over what the “point” of these scenarios was, so I wanted to take a moment to talk about that a bit.

Something I think about a lot is how to make RPGs more accessible as a hobby. We have a vision of what it means to play a roleplaying game in our heads: It’s a group of maybe a half dozen people sitting at a table for four to six hours. Maybe, if we’re feeling really ambitious and a little “rules light” about it, we imagine a “lightning-fast” two or three hour session instead. It’s more likely to go the other way, though, with the same group of people doing a long session once a week for several months or years. If you close your eyes, you can probably see them huddled around the table in your dining room or the corner of your local gaming store. Heck, they might be there right now! They’re probably having a great time!

But this is a vision — a preconception, if you will — that makes it hard to sell people on a new RPG. The typical RPG player is missing out on all kinds of awesome games that they would really love if they ever tried them, but they haven’t because trying a new RPG feels like a big commitment. This is even more true for people who have never played an RPG before!

Compare this to a typical board game, where the play time is rarely longer than a single evening. Many board games, in fact, can be played in less than an hour, providing an easy gateway for new and casual players to get hooked on the board game experience, thereby creating the next generation of gamers interested in longer and more complicated games. At a game store or convention, in fact, we even have an expectation that we can run or play short demos showcasing the basic gameplay of a game in just a few minutes.

If you’re interested in a board game (or board games in general), it’s easy to get a taste of it. If you’re a GM or a game store that wants to let people know about a cool new game, it’s easy to give them a taste of it.

How much is our vision of “how RPGs are played” getting in the way of actually discovering cool new RPGs? Can we change the way that we think about RPGs?

One solution to this problem, of course, is an open table, and I talk about that in the Open Table Manifesto.

But is there a way we could also give people a “casual dip” into an RPG? Is it possible to give them a taste of an RPG in twenty of thirty minutes?

Yes.

I’ve been working on these basic ideas for a few years now, and I’ve heavily playtested this concept in a variety of settings — at my home table, in game stores around the country, and at gaming conventions.

And it works.

SETTING THE SCENE

Since RPGs generally aren’t set up to support this kind of play, you will need to do a little prep.

RULES: If the players are already familiar with the rules, that’s great. If you’re planning to introduce new players to the game, though, you’ll probably have more success with relatively simple games. Or, with more complicated games, you’ll want to give some serious thought to how you can strip the game down to its most essential mechanics.

Either way, I recommend having a cheat sheet prepped for the game (and enough copies so that every player can have one).

It can be very effective to literally script and practice a 5-minute introduction to the game. For my introductory scripts, I’ll often prep a short outline with bullet points that I can easily run through.

CHARACTERS: If you’re using an RPG in which characters can be created even by completely new players in 5 to 10 minutes, then you can easily include that in your quick shot session. Examples of this include the original 1974 edition of D&D, Magical Kitties Save the Day, and Technoir.

Tip: Something that will often trip you up here is buying equipment, which can turn into a huge time sink. I recommend prepping prebuilt equipment packages to simplify and speed up the choices being made. Of course, RPGs in which equipment is handwaved or can be handled through preparedness/load mechanics are also great.

What you’re often looking for here is a game in which characters are generated, rather than being built. These usually includes key decision-making by the player, which has the positive effect of getting them creatively invested in their character, but keep that decision-making focused through the generative elements.

If character creation in your system of choice isn’t lightning fast, you’ll want to have a stack of pregen characters that the players can choose from.

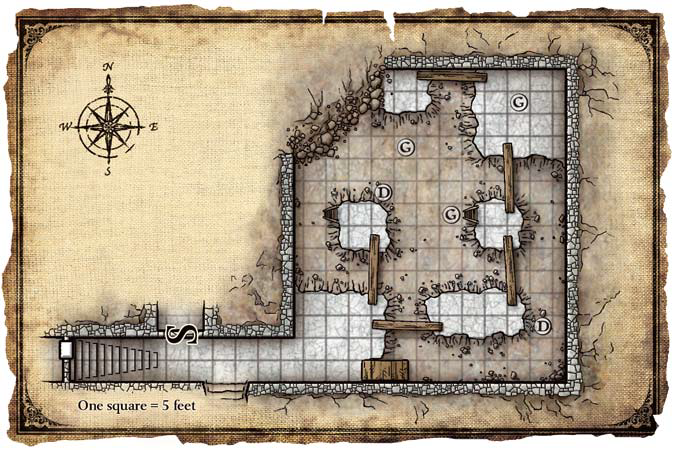

SCENARIO: In designing and running quick shot scenarios, what I’ve found works best is basically one complex scene with (a) a specific goal or problem, but (b) no prescribed solution for achieving that goal or solving that problem (so that the players have to engage in some creative problem-solving).

A micro-raid is often the perfect fit for this: A simple, secured location with multiple access points to choose from and a couple or three defensive measures that need to be confronted or overcome. Also take a peek at The Art of Pacing: Running Awesome Scenes for practical tips in structuring non-trivial scenes.

An easy trap to fall into here is just running one big combat scene, particularly in a system where the typical combat encounter takes 20 minutes to run. In practice, for a quick shot, this creates a very monotonous and unsatisfying experience. Combat can certainly be part of the equation (particularly in a system where it can be resolved quickly), but you’re going to get the best experience from a scenario that offers a more diverse range of options.

Finally, adding some sort of unexpected twist or surprise to the scenario goal is ideal, since it will help you nail the landing.

OTHER SUPPLIES

In addition to the rulebook, cheat sheets, character sheets, and scenario sheet, you’ll also want pencils, paper, and dice. I’ll keep all of these together in a file folder or small box, so that I can, for example, pull out my Over the Edge: Hijack Express pack as easily as I might snag a board game off the shelf.

DEMO GAMES

If you’re running a quick shot as a demo at a game store or convention, you’ll want to take a little extra effort to give the RPG an attractive, eye-catching display. This is something that often happens naturally with a board game when you lay out the board and other components, so it can be easy to overlook. But this is an approach I’ve had success with.

- Stand the book upright so that its cover art can do the selling for you.

- Lay out the character sheets, pencils, and dice in a well-organized way.

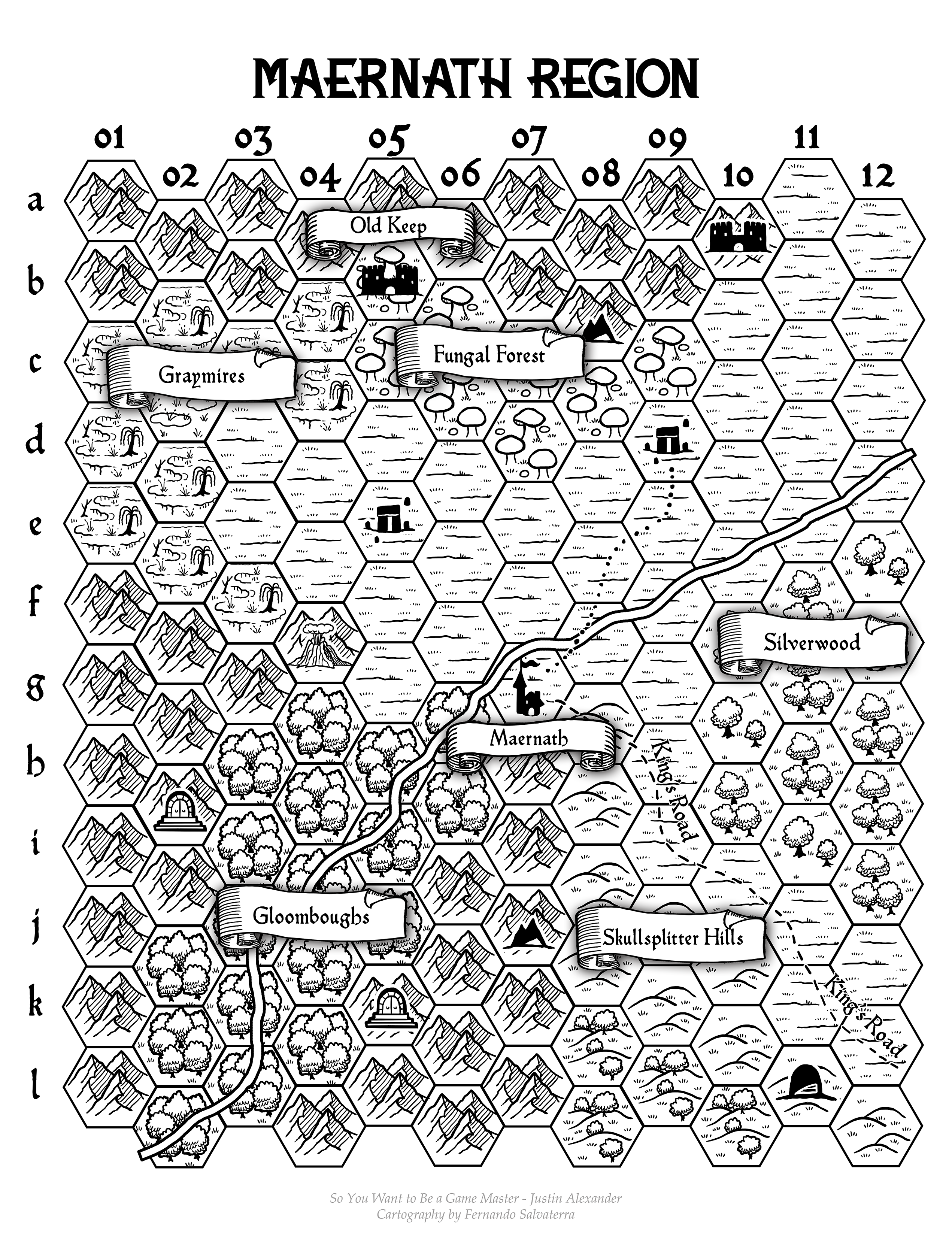

- Try to find some sort of graphical centerpiece to tie the whole thing together. Over the Edge, for example, features a poster map of the Edge that you can place in the center of your demo area. Monte Cook Games, on the other hand, has Numenera game mats you can use.

- The GM screen for a game is already designed to stand upright. I recommend not using the screen for a quick demo like this (as it cuts you off from the person you’re sharing the game with), but having it set off to one side is usually a great visual showcase.

If you can, create a standee for the game which clearly states the intended length of the demo. Something like, “Have an adventure in just 20 minutes!” (In our playtests, we found that if we just announced an “RPG Demo,” people’s preconceptions would assume a multi-hour commitment. Even verbally saying that it only takes twenty minutes seems less effective than displaying it in print.)

RUNNING THE QUICK SHOT

A quick shot is, quite obviously, a fraction of the length of a “typical” RPG session. To make the experience fun and worthwhile, you absolutely have to (a) hit the ground running and (b) keep the pace fast-and-furious.

The scenario goal should be big, bold, and clear, and it will help give both you and your players focus.

- Don’t dither — make, quick decisive rulings.

- Make big, bold choices.

- Push the players hard and, if possible, put them on the clock.

- Remember that there are no long-term consequences, so take big chances.

I also like to use a kitchen timer: Set it to 20 minutes and go, go, GO! It’ll keep you focused and help shape the pacing of the session. You might even find it effective to put this where the players can see it, reminding them that they’re literally on the clock.

Good gaming!

QUICK SHOTS

Magical Kitties Save the Day: The Witch’s Hut

Over the Edge: The Hijack Express