Go to Table of Contents

This company of mapmakers rose to prominence nearly three centuries ago when they began producing incredibly detailed maps of the Serpent’s Teeth archipelago based on the exploration ships that were sent into the southern reaches of the island chain by Yrkyth Vladaam. These charts greatly expanded trade throughout the Whitewind Sea during the decades leading up to the Great Sea War.

The Red Company of Surveyors still uses as its mark the great seal Yrkyth used when he was head of the household. The company’s influence considerably declined following Yrkyth’s disappearance in 651 IA, but continues to be known for their accurate navigation charts.

The company’s chart-making workshop is located in Oldtown. Their apprentices work as boy messengers on the Docks, purchasing interesting chart data from docking ship captains. (Some of these apprentices are part of Part 18: Vladaam Drug Running.)

The guild uses a diamond-feather badge (representing the quills of the cartographers, but also having deeper meanings for the Brotherhood of Yrkyth).

| DENIZENS | Location |

| Guildmaster Essetia | 1st Floor (25%), Area 8 (25%), Inner Sanctum (10%), or not present |

| 2d6 Chartmakers | 1st Floor |

| Captain of the Iron Fleet | Area 4 (10%) |

Chartmakers: Use artisan stats, Ptolus, p. 606.

- Proficiency (+2): Cartographer’s tools

- Equipment: diamond-feather guild badge, Vladaam deot ring

Guildmaster Essetia: Use mage stats, MM p. 347. AC 16 (bracers of defense, ring of protection).

- Proficiency (+3): cartographer’s tools, Arcana, History, Insight, Persuasion

- Combat Equipment: wand of magic missile (1d6+1 charges), portion of superior healing, dagger, light crossbow (20 bolts)

- Magic Items: dust of dryness (x2), scroll of identify, bracers of defense, headband of intellect, ring of protection

- Other Equipment: backpack, rations (x6), scroll case, spellbook, spell component pouch, pearl (x3, 100 gp each), 100 gp, Vladaam deot ring, diamond-feather guild badge

Cantrips (at will): dancing lights, light, mending

1st level (4 slots): alarm, comprehend languages, detect magic, identify, shield

2nd level (3 slots): detect thoughts, invisibility, web

3rd level (3 slots): clairvoyance, dispel magic, fly

4th level (3 slots): locate creature, stoneskin

5th level (1 slot): bigby’s hand

Oldtown

Ridge Road – E5

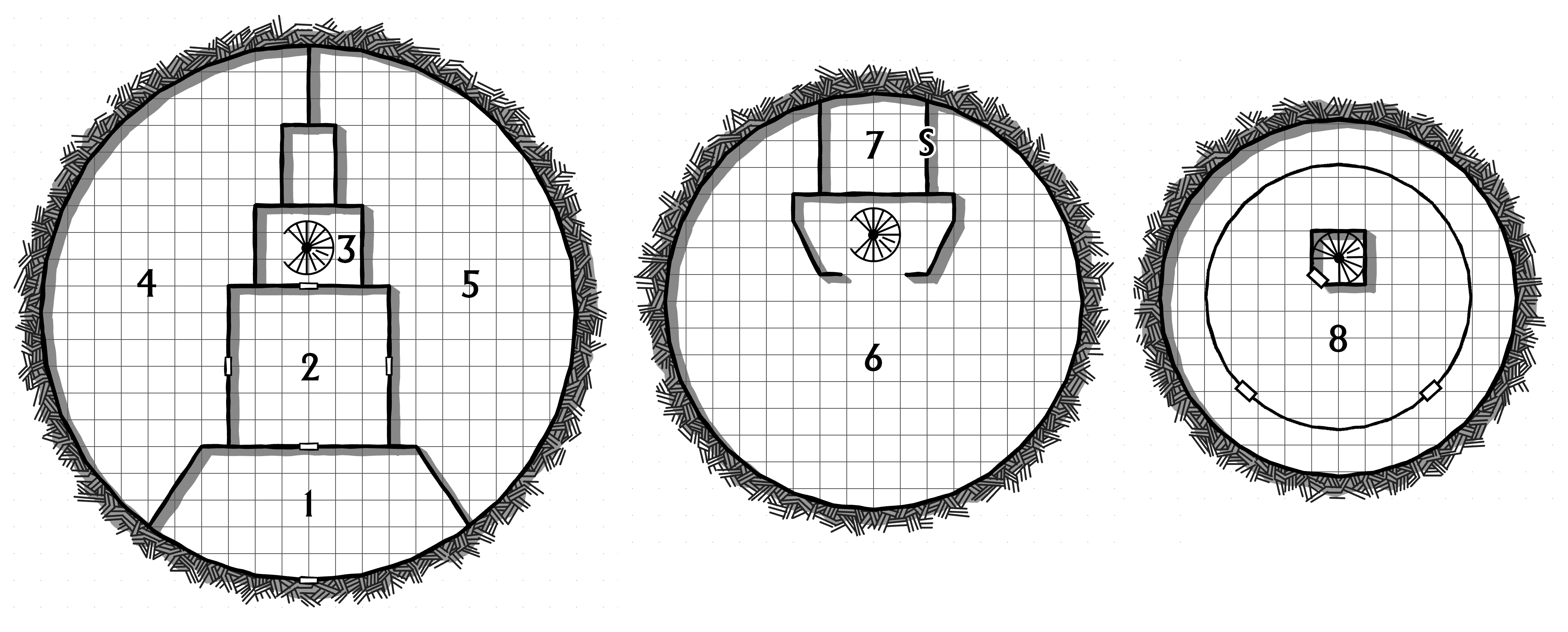

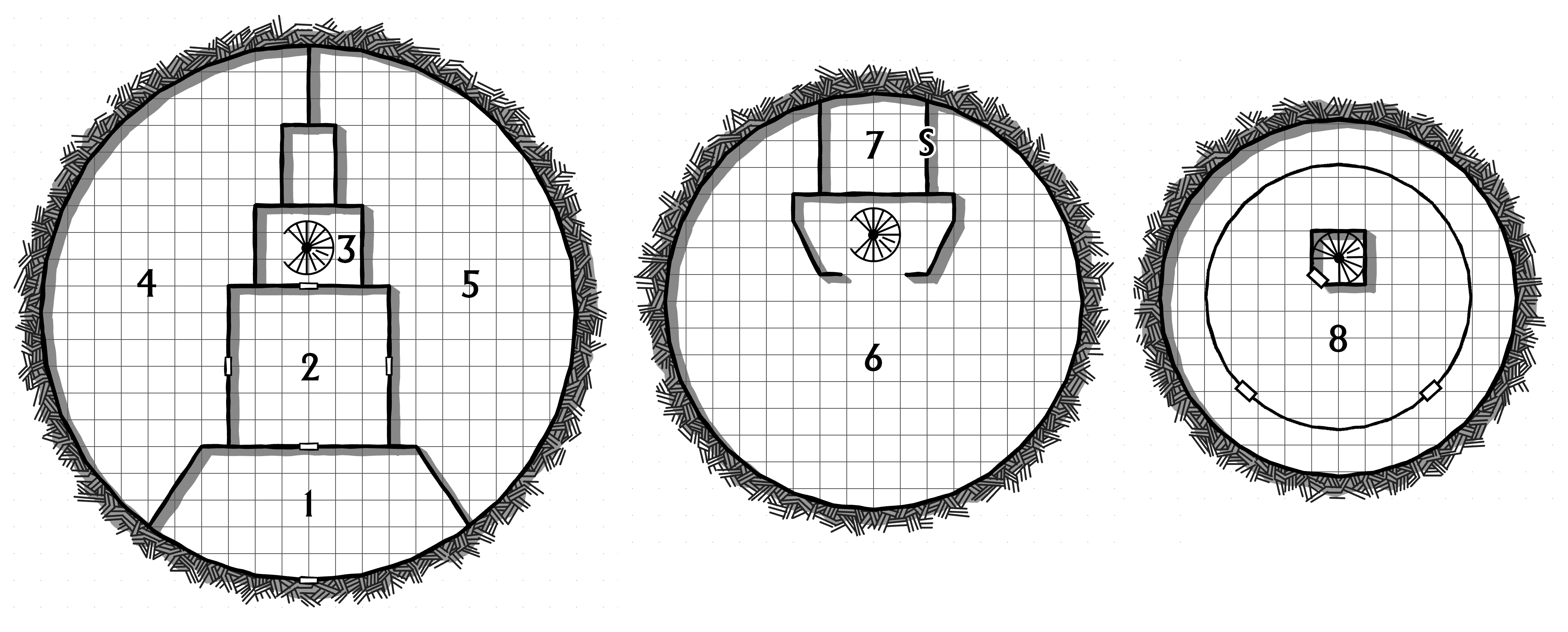

EXTERIOR

A three-storey, stepped tower. A balcony runs around the perimeter of the third floor. Red and gold banners hang around the circumference of the second floor.

AREA 1 – ENTRY

A small writing desk off to one side of the chamber is typically manned by a guildmember who will inquire after the business of anyone entering.

FIRST MAP OF THE GUILD: Hanging on the wall to the left of the entrance there is an old map of Ptolus. A DC 10 Intelligence (History) check can note the major departures from the modern city:

- Oldtown is nearly in its current state.

- The Nobles’ Quarter is present, but the estates are smaller and less luxurious.

- There are no bridges to Rivergate, and there’s only a single large, walled manor there.

- North of the river, where the Temple District is today, there’s a small cluster of buildings around the Cathedral.

- There’s an area labeled “Guildsman District” clustered around the top of the ramp leading down to the Docks. (Today, this area would be considered the easternmost part of Midtown.)

- South of the river, Oldtown seems to spill out off the mesa and into the western reaches of what’s today the South Market, but the buildings don’t even reach as far as Emerald Hill.

CHART OF THE WHITEWIND SEA: Hangs on the wall to the right of the entrance. Clearly archaic. Drawn by the surveyor who founded the Brotherhood of Yrkyth. (The letters of his name have been cleverly crafted to resemble the diamond-feather symbol of the guild.)

AREA 2 – GREAT SEAL OF YRKYTH

The marble floor of this entry chamber is tiled to form the Great Seal of Yrkyth.

AREA 3 – STAIRS UP

These stairs lead up to Area 6 and the door to Area 8.

AREA 4 – GUILD GATHERING HALL

A long, mahogany dining table runs down the center of this room. The benches to either side of it are padded with purple velvet.

FIREPLACE: On the right-hand wall, there’s a large fireplace. It’s cleverly designed to pump heat under the stone bench which lines the curve of the outer wall.

BOOKCASE: Holds journals and logs donated (or purchased) from various ship captains over the past several centuries.

AREA 5 – CHARTMAKER’S ROOM

This room is filled with drafting tables and associated tools. Most of the guildmembers here are engaged in simply copying maps from the guild’s library (Area 6), but occasionally there will be a new map being drafted.

DC 12 Intelligence (Investigation): Among the mapmaking equipment there is a table with financial records.

- This includes a Tithe Payment of Rent: The boy apprentices of the Red Company of Surveyors are housed in the Vladaam apartments on Crossing Street in Oldtown.

- GM Note: This is not the apartment building occupied by chaos cultists in Night of Dissolution, but one of the neighboring buildings. See Part 15: Oldtown Apartments.

AREA 6 – MAP LIBRARY

This library contains detailed charts of the Whitewind and Southern Seas, but also maps of Palastan, Cherubar, the Plains of Rhoth, the Sea Kingdoms, Ren Tehoth, the Plains of Panish, the Prustan Peninsula, and even the distant lands of Uraq.

ACCESS: The guild charges 100 gp for access to the map room. There is an additional copying charge per map. (These maps represent valuable commercial intelligence.)

LIBRARY: The library grants a +2 bonus to navigation- and geography-related checks.

TREASURE HUNT: A conjoined DC 16 Intelligence (Investigation) and DC 20 Wisdom (Survival) check requiring 1d6 days per check can allow a researcher to turn up a map to a potentially interesting location.

HIDDEN SWITCHES: There are six hidden switches located around the room. If activated in the correct sequence, they open the 4-ft. thick stone wall leading to Area 7. If activated in an incorrect order, a magical trap is triggered which summons a chain devil and sends a mental alarm to Guildmaster Essetia.

- DC 10 Intelligence (Investigation): To find one of the six hidden switches.

- DC 14 Intelligence (Investigation): To find two of the six hidden switches.

- DC 20 Intelligence (Investigation): To find all six hidden switches.

- DC 25 Intelligence (Investigation): To realize there’s a trap triggered with an incorrect activation sequence. A second DC 25 Intelligence (Investigation) or a DC 16 Intelligence (Thieves’ Tools) check can determine the correct sequence.

AREA 7 – ENTRANCE TO THE INNER SANCTUM

Lit with red everburning torches, this stairwell hidden within the wall of the guildhouse leads down to Area 1 of the Inner Sanctum.

AREA 8 – GUILDMASTER’S QUARTERS

DOOR – MAGIC MOUTH: A gargoyle on the door will animate and speak to anyone approaching, passing messages to Essetia if she’s inside. If Essetia is not present, the gargoyle will “take a message” and give it to her when she returns.

- Door (Strong Wood): AC 15, 27 hp, DC 24 Dexterity (Thieves’ Tools)

SITTING AREA: Comfortable chairs with griffon-carved backs and a bed of luxurious feather-down. Large windows look out onto the balcony.

WRITING DESK: The top is closed and locked, requiring a DC 14 Dexterity (Thieves’ Tools) check. The desk contains:

- Correspondence Regarding the Hand of Malkith

- Report Concerning the Erthuo/Sadar Affair

- An engraved box of oak containing a cutting from a tree (papery-thing, silver-grey bark and white wood) and Letter from Essetia to Ulloth.

- A red pouch containing 150 pp and Letter of Thanks from Godfred Vladaam.

DC 12 Intelligence (Investigation): A chest is hidden under the bed.

- 469 gp

- potion of fire shield

- scrolls (see invisibility, mage hand, feather fall)

- Oath of the Brotherhood of Yrkyth

IRON COFFER: 10% chance of being present.

- 500 gp

- 40,000 sp

- 50,000 cp

- Instructions to have the Ithildin Couriers ship to the Red Company of Goldsmiths on Gold Street (see Part 12).

AREA 9 – GUILDMASTER’S BALCONY

The balcony encircles the entire third floor of the guildhouse. A beautiful view of the city and out across the Whitewind Sea on one side, and across Oldtown towards the Nobles Quarter and the Spire in the other direction.

TRIPODS: There are two tripods set up on this balcony. One contains a sextant, the other a telescope. The guildmark on each of them marks them as creations of the Red Company of Founders (sees Part 11).

Go to Part 14B: Inner Sanctum of the Surveyor’s Guild