SESSION 38D: ARROWS & SKULLS

May 9th, 2009

The 21st Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

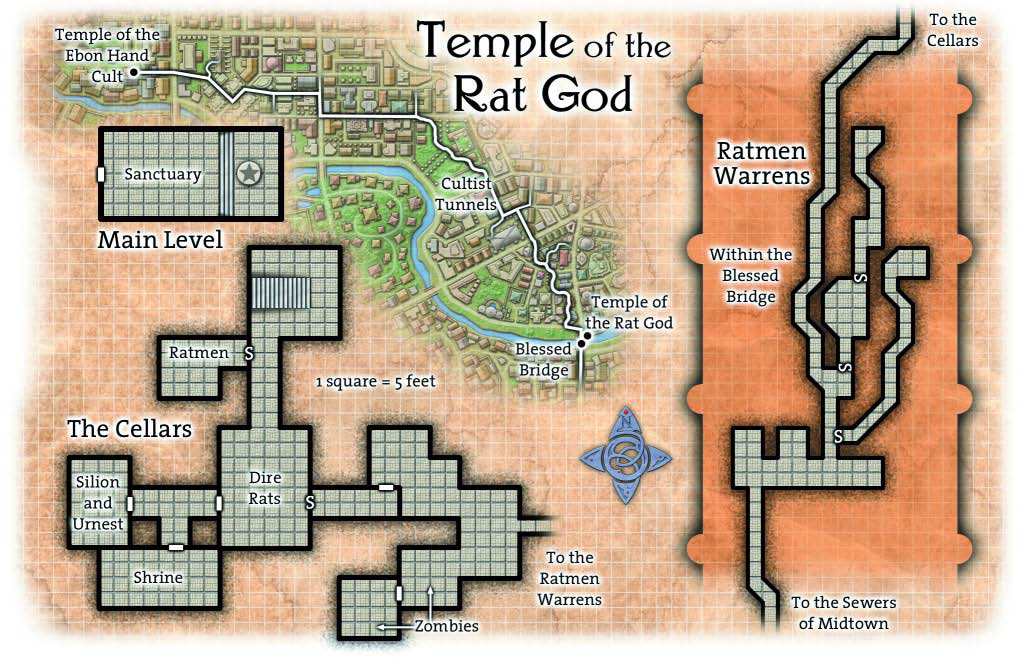

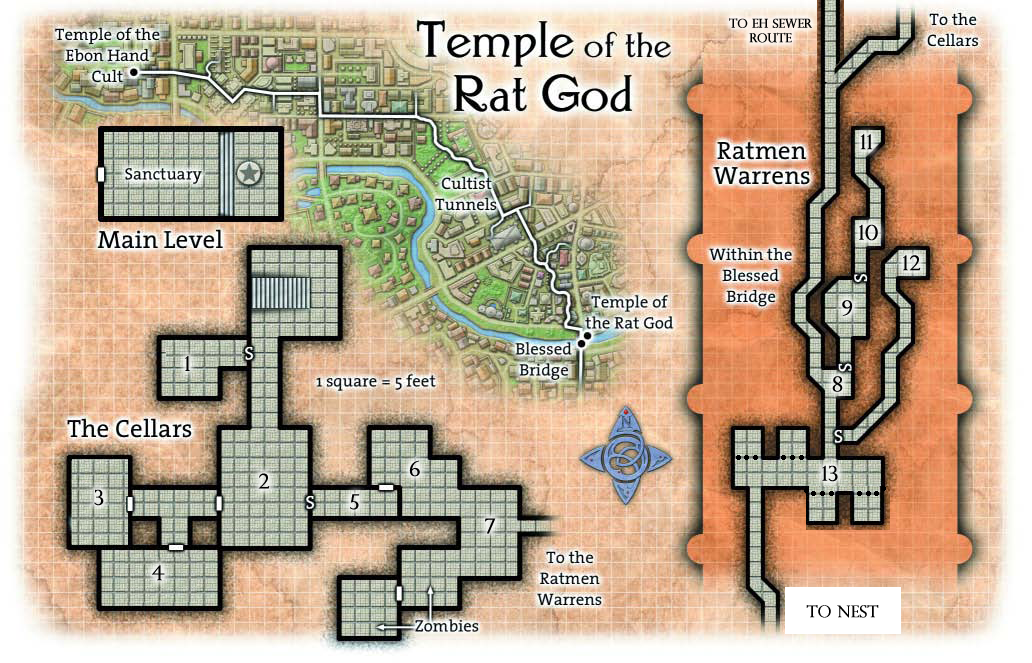

Deciding that there wasn’t more they could learn here (safely, anyway), they returned to the Ghostly Minstrel and joined up with the others. They compared notes, passed on the thought of wandering through the sewers looking for an entrance that might not even exist, and decided that a frontal assault was called for… albeit disguised in robes.

They stopped by Ebbert’s on the way out of Delvers’ Square and Tee did her best to match the robes she had seen the ratmen wearing. They didn’t think the disguises would last for long, but if it could buy them just a few seconds it might make all the difference.

They ambled along the length of the Blessed Bridge, chose an opportune moment when the crowds seemed to thin a bit, and then Tor and Agnarr led the way through the door. Unfortunately, with their eyes adjusting from the bright noon-day sun to the dim light of the sanctuary, they failed to notice the ratmen lurking to either side of the entrance. They were nearly skewered in a hissing dance of blades before freeing their own swords from below their robes.

After a chaotic skirmish near the door, they managed to push the ratmen back down the length of the hall. Tee, Elestra, and Nasira followed them in, while Ranthir kept an eye on the street to make sure the commotion wasn’t attracting attention. Meanwhile, more ratmen were racing towards them from the far end of the sanctuary.

Agnarr chopped one down. Tee dropped another in mid-step with a sharply aimed arrow. Then Tor sliced his blade precisely between the ribs of one (lacerating his heart), before ripping it free in an arc of blood (narrowly missing Agnarr, who literally leapt over the blade) and plunging it into the last of the ratmen.

Silence abruptly fell in the sanctuary. No one on the street seemed to have noticed what was happening, and Ranthir slipped through the door and shut it behind him.

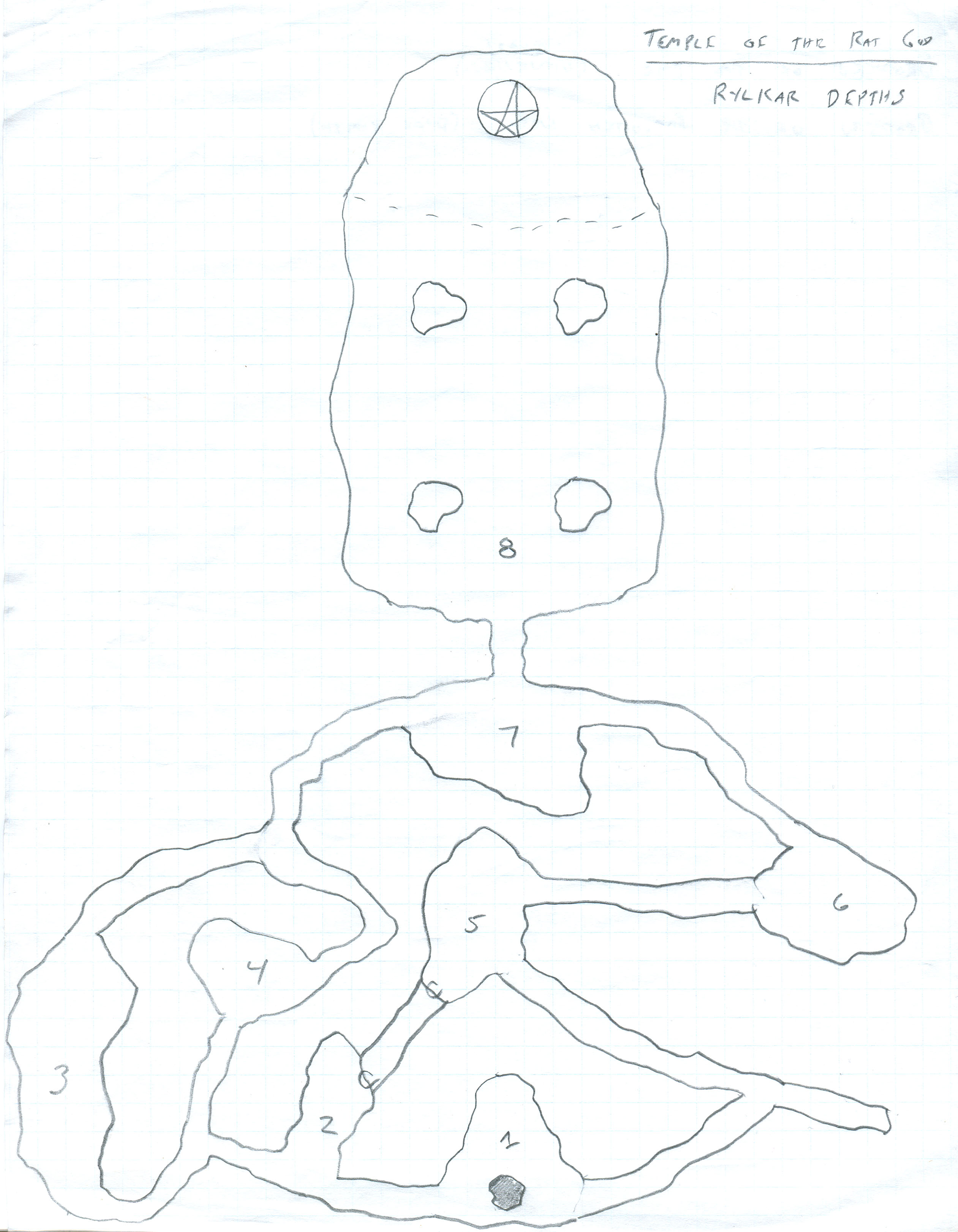

Tee was suspicious of the statue, and a quick investigation confirmed that it could be easily slid to one side, revealing a set of stairs leading to a lower level.

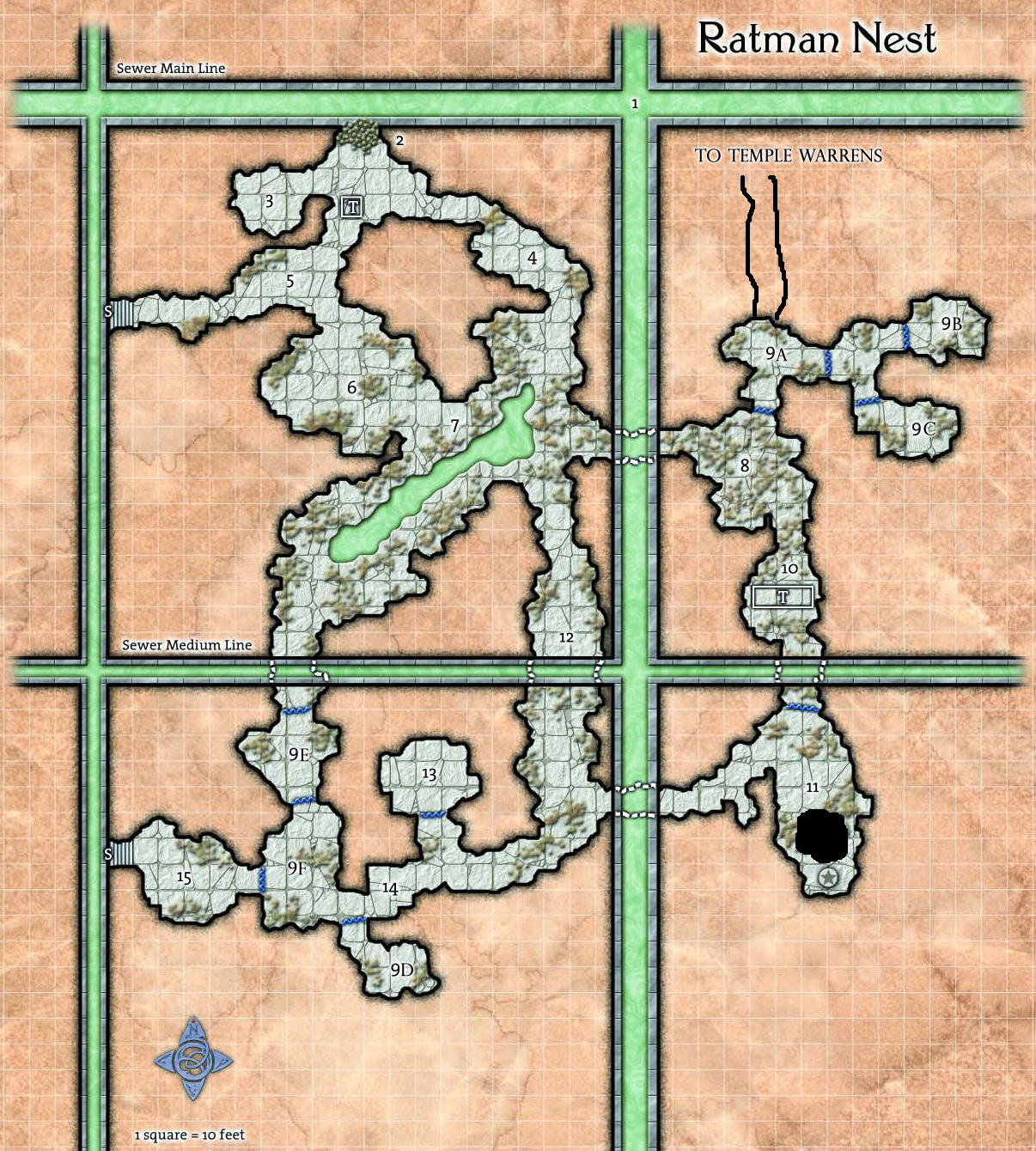

The air below was thick with smoky light and they descended with great caution into a chamber of bare stone. A single hall passed away to the south and Tee led the way, carefully probing every inch of the way. Her attention paid off: A depressable cobblestone gave way under her hand, causing a section of the wall to swing aside.

The room beyond was filled with carefully arranged piles of bulky, broken machinery bearing the unmistakable patina of age. Kneeling amidst this equipment – her back to the door – was a single ratling dressed in pale yellow robes.

“Not now! I don’t want to be disturbed!” she hissed.

Tee put an arrow through the back of her skull.

“… was that Silion?” Tee looked back at the others. “I think that was Silion!”

Agnarr removed the iron collar from his own neck and snapped it around Silion’s. Then they stuffed her body into Tee’s bag of holding.

A cursory inspection of the equipment Silion had been studying revealed that all of it belonged to a single, massive machine: An exoskeleton that, while not identical to it, nonetheless bore an uncanny resemblance to the one they had discovered in the Shuul workshops beneath the Foundry.

Heading further into the complex they passed through a large room with life-size statues of ratmen standing in each of its four corners. The door from that room led into a narrow hall, which crossed a T-intersection a dozen or so feet further on.

Tor and Agnarr had scarcely passed through this door before a hulking ratbrute leapt out of the connecting hallway with a bellowing, screeching cry. The dragon pistols he wielded in both hands blasted chunks of stone out of the walls above their heads as they ducked almost in unison. Then their blades were out, pursuing the ratbrute as it backed down the hall, continuing to blast away with his pistols.

“It’s Urnest!” Nasira shouted.

The ratbrute dropped his pistols and drew a pair of swords in their place.

“Who was the woman?” Tee cried out, taunting him.

The ratbrute blanched.

“That’s right!” Tee shouted. “I said was!”

“No! You’re lying! Silion could never be beaten in her own halls!”

Ranthir seized that moment of weakness, conjuring bands of wrought iron that snapped shut around Urnest’s limbs. Urnest managed to narrowly avoid one set of the bands, but the other locked sharply around his right arm and leg, forcing him to drop one of his swords and making it difficult for him to parry that assault of Tor and Agnarr.

“The gods of chaos will fea—“

Tee put an arrow through the back of his open mouth.

MORE CORPSES

“That’s two of them,” Tee said, mentally checking names off a list she had just decided to start keeping.

In a room at the end of the hall they found a small bedchamber that they guessed belonged to Silion and Urnest. Hidden on a small wooden shelf built into the bedframe they found an iron coffer containing a copy of The Truth of the Hidden God and several important pieces of correspondence.

CHAOSITECH SHIPMENT INSTRUCTIONS

I have received word through the Black Voice. The shipment will arrive at Mahdoth’s on the 25th. Come to the asylum door at midnight and you will be given entrance. Go to the western cells.

LETTER TO URNEST

Urnest—

Illadras asks for more slaves to be sent to the Crossing Street Mansion.

On the back of the second note, in a different hand, rough tallies had been made indicating that only three slaves were available for transport. A short annotation read “purchase additional stock from the enclave”.

REPORT ON THE EBON HAND

Silion—

Malleck was furious when I told him we could only deliver three of the children that had been promised. He threatened to “turn the full might of the Ebon Hand” against us. As you requested, I offered to supply him with other slaves, but he is insistent that his experiments require only the youngest blood.

Valla

None of them liked the sound of that. And Elestra was the one to draw a connection between “the youngest blood” and the children who had gone missing in Midtown.

“There are children down here?” Tee could feel her blood boiling.

“It sounds like they were going to be sent to this Malleck person,” Elestra said.

“If they were only just kidnapped, it’s possible they haven’t been delivered yet,” Ranthir suggested.

“Then we’ll find them,” Tee swore. And Tor was quick to agree.

But if there were children down there, then there must be more of the complex than they had discovered. They returned to the large chamber with the four ratmen statues and Tee performed a more thorough search. In the process she realized that they had triggered an alarm by passing through the chamber (“Which is how Urnest was waiting for us,” Tor said), and she also discovered a secret door leading out the far side of the chamber.

They entered a twisted, odd-shaped room filled with nest-like piles of refuse and garbage. From somewhere beyond the contorted corners of the room Tee could hear low, hissing voices. Unfortunately, as Tee glided silently into a position where she could see two ratlings who were chatting amongst themselves, she stumbled over an odd piece of metallic junk – causing it to skitter loudly across the floor. The ratlings whirled towards her… and then a ratbrute came lumbering around the corner. Tee cursed. Loudly.

Agnarr, who had been waiting impatiently back by the door, came charging in with Tor on his heels. They quickly cut down the two ratlings and Agnarr followed one of Tee’s arrows to engage the ratbrute. Tor didn’t even pause, heading around the next corner and—

“Zombies!”

Nasira, darting around the melee where Agnarr was facing down the ratbrute, came up next to Tor and, with a burst of holy energy, forced the zombies back into a corner. But beyond the zombies there was another ratbrute, this one throwing open a door… releasing even more of the shambling undead.

Nasira shouted a prayer and a second burst of holy energy lashed out: Several of the zombies were rendered instantly into dust, while others fled before her holy wrath.

With the zombies unleashed, the second ratbrute turned back to the attack. But by that point, Elestra had joined Tor and Nasira. She reached out into the stones and called upon the Spirit of the City, forcing them to split and crack; break and jut out wildly in all directions; an earthquake tremor shaking the ratbrute and his zombie minions from their feet; crushing them in broken stone.

The ensuing melee was chaotic – fought amidst unstable stone – but eventually Tor managed to hack down the ratbrute while Agnarr mopped up the zombies.

They took a few minutes to poke through the ratling nests, discovering amidst the garbage a damaged scrap of paper.

DAMAGED NOTE

–take one of the kennel rats through the northern sewer route and speak to Malleck about it. It’s important that—

There was a narrow tunnel that twisted deeper into the depths of the bridge. They followed it, eventually coming to a north-south T-intersection.

“Which way?”

The universal decision was north: Malleck had been the one who wanted the children, and they were eager to find the sewer route that would take them to him.

Running the Campaign: The Secret Life of Silion – Campaign Journal: Session 39A

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index