Up until this point, a lot of this blather about “game structures” may have sounded like it was something that only game designers need to waste their time with.

But, to the contrary, game structures represent the primary and most important tool in the GM’s toolbox. The more game structures a GM has mastered, the easier they will find it to prep and run their scenarios. The fewer game structures a GM knows, the more limited their scenarios and the more difficult their prep becomes.

(The argument can also be made that, fundamentally, all GMs need to act like game designers: An RPG without a scenario is like Monopoly without a board. Or, to put it another way, if Monopoly were packaged like a typical RPG it would come with rules for moving your pawns and buying properties, but it would expect the group to design its own boards. Scenario design is game design.)

To demonstrate what I mean about using scenario structures as tools, let’s take the example of a fairly straightforward adventure concept:

The PCs have been tasked with accompanying a clerk who has been charged with acting as the proxy for the Duchess of Canterlocke to bid for a dilapidated estate standing opposite the Dweredell Gardens. The PCs are to protect him while finding out more about the other parties interested in the estate and the suspected cult activity surrounding the estate.

Fifteen years ago, my mastery of game structures was limited. I basically had two of them: Dungeoncrawling and linear railroading. Faced with this concept for an adventure scenario, I would have been forced to resort to the linear railroad: A pre-programmed sequence of scenes that the PCs would experience. (To my fictionally retroactive credit, I would have probably tried to make those scenes as flexible as possible because I wasn’t actually a fan of railroading. But I would have been fighting my prep structure, and that usually means a lot more prep.

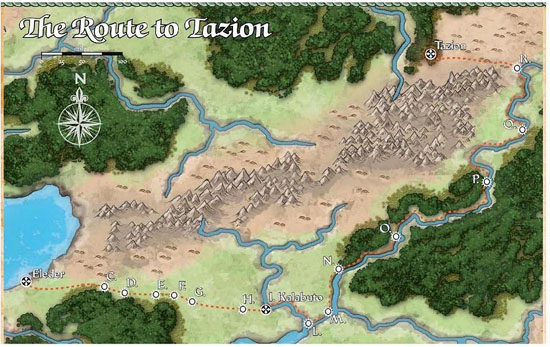

In a similar fashion, you can see how the lack of a game structure for wilderness adventures has resulted in most modern adventure modules presenting overland travel as a linear sequence of pre-programmed encounters:

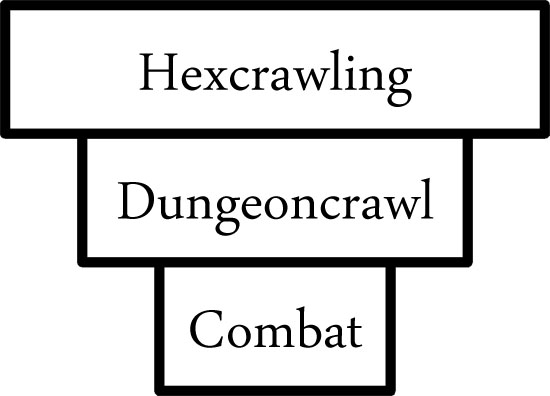

But today, with a wider array of game structures at my fingertips, I find it relatively trivial to break this scenario concept down in a way that’s easier to prep, easier to run, and offers the players a much greater freedom in how they want to approach the scenario.

(1) “The PCs are to protect him…” I’m assuming this means that there will actually be something to protect him from. To prep this, I draw up a list of threats (i.e., the attacks that will be directed his way). These might be triggered by location (“when he reaches Water Street, the assassins strike”), but just putting them on a timeline will probably work, too.

(2) “To bid for a dilapidated estate…” When I prep a large social or business gathering, I prep two tracks: First, I prep a roleplaying profile for each significant participant. Second, I prep a list of significant events.

Sometimes the significant events are on a timetable. Sometimes they’re keyed to particular NPCs or locations. Sometimes they’re just a list of conversation topics that are popular at the party. (Ultimately, it’s whatever makes sense and is most useful to me. More details here.)

(3) “… a dilapidated estate standing opposite the Dweredell Gardens.” Here we come to a key question: Is the estate something that the PCs are supposed to explore room-by-room (like a haunted house)? Or will we just be just be treating it as a backdrop for the auction? The former gets prepped (and run) as a dungeoncrawl. The latter gets prepped with a few brief descriptions and maybe a generic floorplan if I think it’ll be important for some reason.

It might also be both: The mansion itself might just be a backdrop for the auction; but the family crypts under the mansion might shift us into a ‘crawl. Or maybe the mansion is treated as a backdrop during the auction and then we approach it as a ‘crawl during the night when all the ghosts from the Well of Souls come out.

(4) “The suspected cult activity around the estate.” Like most mystery structures, I’m going to default to node-based scenario design to break it down into easy-to-manage and easy-to-design chunks. To launch players into the node structure, I’ll liberally seed clues in the threats in #1, the NPCs in #2, and the rooms in #3 (if I went for a crawl-based structure there). A sample node list might look something like this:

- Cultist Assassination Team

- Shrine of the Black God

- Temple of the One-Eyed Priest

- Councilor Jaffar (Secret Cultist)

The assassination team is a proactive node that attacks the clerk the PCs are guarding. One of the assassins has a distinctive tattoo (asking around town indicates people have seen people with similar tattoos hanging around the Shrine of the Black God). Questioning any of the assassins will reveal they were sent from the Temple of the One-Eyed Priest. Maybe one of them has a note signed by Jaffar telling him to kill one of their fellow assassins once the job has been completed.

And so forth.

BREAKING THAT DOWN

The first thing is the scenario hook: The Duchess of Canterlocke wants to hire the PCs to guard a clerk for her.

That hook is connected to a simple timeline structure: The clerk needs to head to the estate at Time A; assassination attempts will be made at times B and D; the open house and auction will begin at time C.

That timeline has additional triggers in it: Clues on the assassins will trigger the node-based investigation. Escorting the clerk to inspect the house will trigger the ‘crawl of the house. Escorting the clerk to the auction will trigger the social-based party structure.

The ‘crawl of the house will probably include triggers for combat (undead in the crypts below the house or whatever). The party structure will contain additional clues triggering the node-based investigation. And the node-based investigation will lead to both the Shrine of the Black God and the Temple of the One-Eyed Priest, which are probably both prepped as dungeoncrawls, too.

USING THE RIGHT TOOLS

Like most projects, once you have the right tools, it’s just a matter of identifying the right tool for the job and then using it.

For the sake of argument, let’s imagine that we instead used all the wrong tools:

(1) We try to prep escorting the clerk across Dweredell as a ‘crawl: That means prepping every street with a keyed encounter so that the PCs will encounter content no matter which streets they decide to walk down. (Result: Way too much prep, a lot of decisions that aren’t of particular importance to the immediate goals of the PCs, and probably some severe pacing problems.)

(2) We prep the crypts under the house as a timeline of undead-themed encounters: After 5 minutes of explortation we trigger encounter 1; after 10 minutes of exploration we trigger encounter 2; and so forth. (Result: The only meaningful input the players have here is to say “we keep exploring”. Our impulse is probably to at least improvise a map as they explore, but of course that just moves us back towards the dungeoncrawl structure that we’re specifically eschewing for the purpose of this broken example.)

(3) Instead of prepping auction bidders for roleplaying, we instead give ‘em combat stats and roll for initiative whenever the PCs want to talk to them.

And so forth.

Use the proper structures and the prep will be easy and naturally allow your players to make meaningful and relevant decisions. Use the wrong structures (either by mistake or because you don’t know the right structures to use) and your prep will be difficult and your players will struggle to make the choices they want to make.

But what if the right game structure doesn’t exist?