As we wrap up our discussion of the hexcrawl game structure, I thought it might be interesting to take a few moments to revisit a few archaic game structures that have been abandoned by the hobby.

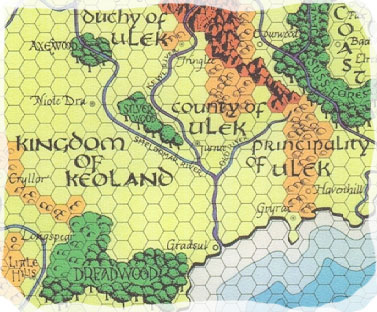

Until recently, of course, the hexcrawl itself could be described as an archaic structure. By 1989 there were a few vestigial hex maps cropping up in products, but none of them were actually designed for hexcrawl play. The 2nd Edition of AD&D removed hexcrawling procedures from the rulebooks entirely. It wasn’t until Necromancer Games brought the Wilderlands back into print and Ben Robbins’ West Marches campaign went viral that people started to rediscover the lost art of the hexcrawl.

Until recently, of course, the hexcrawl itself could be described as an archaic structure. By 1989 there were a few vestigial hex maps cropping up in products, but none of them were actually designed for hexcrawl play. The 2nd Edition of AD&D removed hexcrawling procedures from the rulebooks entirely. It wasn’t until Necromancer Games brought the Wilderlands back into print and Ben Robbins’ West Marches campaign went viral that people started to rediscover the lost art of the hexcrawl.

The original game structure for hexcrawls described in OD&D is actually quite distinct from the hexcrawl procedures I described earlier (which were largely innovated by Judges Guild and than adapted into AD&D). The bulk of wilderness adventures in OD&D focused on castles:

Castles: As stated, the ponds [on the Outdoor Survival gameboard] indicate Castles. The inhabitants of these strongholds are determined at random. Occupants of these castles will venture out if a party of adventurers passes nearby. If passing over the castle hex there is a 50% chance (die 1-3) that they will come out, if one hex away there is a 33-1/3% chance (die 1-2), and if two hexes away there is only a 16-2/3% chance (die 1). If the party is on the castle hex and hails the castle, the occupants will come forth if the party is not obviously very strong and warlike. Patriarchs are always Lawful, and Evil High Priests are always Chaotic. All other castle inhabitants will be either hostile to the adventurers (die 1-3) or neutral (4-6).

This is followed by a random table for determining the occupant of a castle and their guards/retainers. Then specific procedures for each type of inhabitant are provided: Fighters will “demand a jousting match with all passersby of like class”, Magic-Users will “send passerby after treasure by Geas if they are not hostile, with the Magic-User taking at least half of all treasure so gained”, Clerics will “require passersby to give a tithe (10%) of all their money and jewels” and so forth.

A vestigial remnant of this structure survived all the way into the Rule Cyclopedia (where tables were still being presented to randomly determine the attitude of castle occupants), but I’m guessing it’s been essentially nonexistent in actual play since 1980 at the latest. And, unlike JG-style hexcrawling, I doubt these “castle occupant rides forth” game structures are likely to enjoy a significant renaissance any time soon.

(Although, on the other hand, there are some potentially interesting things lurking in there: First, the implied setting – in which civilization is so sparsely populated that feudal lords will ride out to meet travelers who pass anywhere within a dozen leagues of their walls – is a fascinating one. Second, note how the structure provides default scenario hooks: Like the treasure maps seeded randomly into OD&D hordes, the quests proffered by feudal lords can spontaneously transform the aimless exploration of the hexcrawl into specific direction. But I digress.)

The other major procedure for wilderness play in OD&D was the idea of “clearing” a hex of monsters (which was a prerequisite for establishing a barony or stronghold):

The player/character moves a force to the hex, the referee rolls a die to determine if there is a monster encountered, and if there is one the player/character’s force must remove it. If no monster is encountered the hex is already cleared. Territory up to 20 miles distant from a stronghold may be kept clear of monsters once cleared – the inhabitation of the stronghold being considered as sufficient to maintain the monster-free status.

This basic structure was greatly expanded in AD&D. (For example, it added a precise system for determining when and how monsters return to an area, along with all kinds of modifiers – like placing skulls and carcasses as warning signs.) And then it, too, faded away.

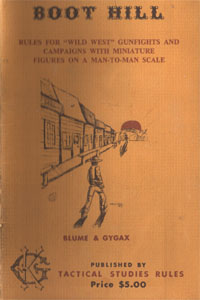

In fact, if you look back at the early history of gaming you’ll find these kinds of explicit game structures all over the place: The system for artifact use in Gamma World, the mercantile models of Traveller, the posse and tracking system for Boot Hill (which, in the 2nd Edition, could be tied into a larger competitive structure of lawmen vs. outlaws), the status points of En Garde, and so forth.

In fact, if you look back at the early history of gaming you’ll find these kinds of explicit game structures all over the place: The system for artifact use in Gamma World, the mercantile models of Traveller, the posse and tracking system for Boot Hill (which, in the 2nd Edition, could be tied into a larger competitive structure of lawmen vs. outlaws), the status points of En Garde, and so forth.

What you had, in short, were a bunch of wargamers who were very familiar with creating specific game structures heavily laden with the details of world simulation: After all, they’d been using precisely defined game structures to model historical battlefields for years. Roleplaying games, however, cracked open the game world, and the game designers were applying game structures to a much wider “world simulation”.

Over time, for a variety of reasons, these explicit game structures became more and more simulationist in nature. As the focus shifted from structures that were fun to play to structures that were accurate “models of the game world”, however, the structures became rather boring and (as the details of the simulation became fetishized) often too complicated to use in actual play to any great effect.

What followed next (and this all happened over the course of only a few short years) was almost inevitable: The explicit game structures became vestigial and then, with the advent of universal systems, disappeared from rulebooks entirely. (With the notable exception, of course, of highly structured combat systems.)

But — and this is important to understand! — the game structures didn’t actually disappear from gaming! They are, after all, essential for play. Instead, a handful of the most popular structures became treated as a sort of common knowledge: Everybody “knew them”, so game designers didn’t bother explaining them. (Although, in truth, very few people really thought about them at all.)

In short, the general sense that playing an RPG consisted of nothing more than “the players tell me what they want to do and then we resolve it” settled over the industry. But, as we’ve seen, this is completely false. What happened in actual practice was that GMs would use a random grab-bag of unexamined techniques that they had collected from people they played with, published adventures, and the occasional unique insight. And this, of course, resulted in a lot of frustrating play.

The lack of explicit game structures in the rulebooks – particularly explicit scenario structures – also helped to make roleplaying games a lot less accessible to people who hadn’t played them before.

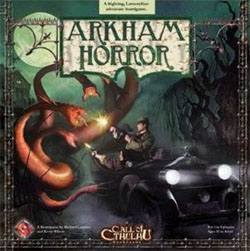

Imagine that you took the rules for the boardgame Arkham Horror and you stripped out all the rules about explicit turn sequencing (i.e., the scenario structure of the game): Instead, you’re left with some rules about how to make skill checks; how far you can move around the board each turn; how to fight monsters; how you can move through gates and close them behind you; how you can fight Ancient Ones if they wake up; and so forth. But… what do you do with all those rules?

Imagine that you took the rules for the boardgame Arkham Horror and you stripped out all the rules about explicit turn sequencing (i.e., the scenario structure of the game): Instead, you’re left with some rules about how to make skill checks; how far you can move around the board each turn; how to fight monsters; how you can move through gates and close them behind you; how you can fight Ancient Ones if they wake up; and so forth. But… what do you do with all those rules?

And that, in short, is what virtually every RPG for the past thirty years except for D&D has looked like to newcomers. (And it is somewhat worrisome to note that every iteration of Dungeons & Dragons since 1983 has reduced the amount of explicit game structure in the core rulebooks until, finally, 4th Edition eliminated dungeoncrawling procedures almost entirely.)

But as we look back at the archaic era of explicit game structures, I think there is something else of import to note that may help to explain why they went way: With the exception of the ‘crawls and a few others, almost all of these game structures were fundamentally incomplete.