VESTIGIAL COLOUR

“From that stricken, far-away spot he had seen something feebly rise, only to sink down again upon the place from which the great shapeless horror had shot into the sky. It was just a colour – but not any colour of our earth or heavens. And because Ammi recognized that colour, and knew that this last faint remnant must still lurk down there in the well, he has never been quite right since.” – The Colour Out of Space, H.P. Lovecraft

Sometimes also referred to as a stunted colour, the vestigial colour is that remnant left behind when the pupating colour launches itself from a planetary mass. Perhaps it is some reaction mass, necessarily abandoned in order to propel the rest of the colour on its way. After all, the laws of Newton demand that in order for anything to go anywhere, something else must be left behind. (Although such a concession to our earthly physics seems hardly in keeping with the colour’s character.)

What is certain is that the vestigial colour’s effects are still felt upon the landscape near it, although in a much less energetic form than the pupating colour: Stunted flora that is “not quite right” in the spring. Wild things that leave queer prints in the winter snow. In a disquiet they cannot quite name, many people flee the region while others are unwittingly compelled to remain.

Perhaps most disturbing is the report that numbers twist queerly in the wake of the colour. In a digital age, who can say what effect the vestigial colour might have upon the memes and videos and telecommunications which fill our every waking hour?

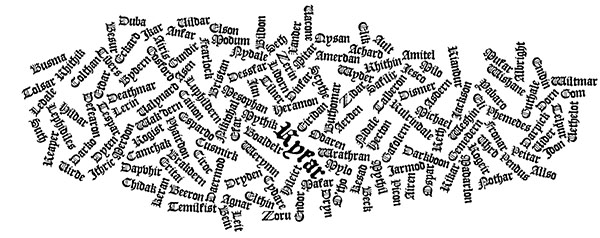

Think of this and it might be true: In order to fuel its ascension, the pupating colour harnesses a memetic processor of incomprehensible scope and nature. When it leaves this world, what it leaves behind it is a stunted and broken version of the same – stripped of value and order and purpose, but nevertheless possessed of the gross mechanisms which seek to assimilate and consume and regurgitate and transform the memetic landscape around it.

These actions are no longer guided by any true purpose or agenda. But the thoughts twist and the spirits of the eye are haunted and slowly, year by year and decade by decade, the influence of the vestigial colour spreads inch by inch. And those beasts and men who are insensibly translated by it are sent ahead as its heralds.

COLOURS OF THE DEPTHS

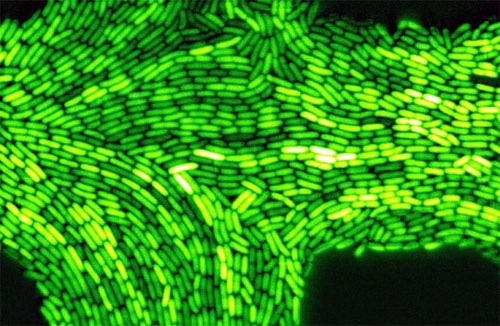

There is another theory which holds that colours were the dawn of life on earth. That they crashed like flaming mercury through ashy and primordial skies, creating meaning and order where they found none.

If such a thing were true, then we are all descended from madness. We would be forced to reconsider the strange and hallucinatory bioluminescences reported by those who explore the abyssal depths of the sea. We would be pressed to call for a greater caution before exploring the strange and unseen truths which lurk in the primeval trenches of the world; those places where the unspoken pressure of the aeon-lost truths which once clung to unnamed ziggurats would seek to crush all human reason.

And if one were to accept that such ancient, primal colours did exist, one might be called to question the identity of that glimmering, shimmering iridescence which clings to the skin of Cthulhu in his immortal, sunken vault.

CYBERCOLOURED NETWORKS

Now we move purely to the hypothetical. Colours act as predators in a memetic landscape made real. They consume thoughts and ideals and genetics – they very concept of a thing – and then take action upon the memetic fiber of existence as we understand it.

Given the existence of such a thing, we must understand that the channels of memetic transmission pose a unique and horrid danger. They are avenues – vast boulevards – down which the colour’s strands can stretch without any spatial relationship. The fiber-optic lasers of our networks can be skewed towards the hideously impossible chromatics of their light. The flickering LEDs of your computer monitor are nothing more than the rainbow-slicked surface of an oily depth.

We look out into the universe and we see the Paradox of Fermi writ in every silent star. We look down and see our entire world bound into a single memetic nexus ripe for the voracious plucking of the colour out of space.

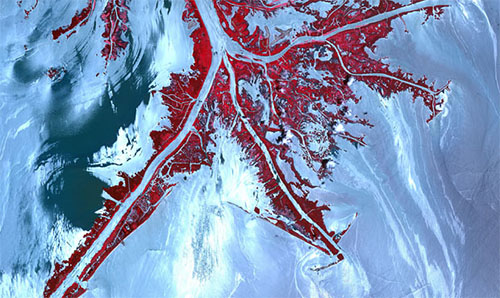

DUST OF THE COLOUR

Another vestige of the pupating colour’s launch is the dust of the colour: As the colour saps its feeding ground of all its memetic life, what’s left behind is a broad expanse of fine grey dust or ash. No wind ever seems to touch or shift the dust of the colour, and most who draw near avoid it almost without thought. If questioned in particular about their aversion, it seems to primarily derive from the fact that the dust of the colour was never properly fixed in their mind; it never truly rested in their thoughts. It simply did not exist for them despite its evident presence.

Similarly, photos of the dust of the colour seem to occlude it more often than not. Such photos stitch themselves together as if the dust were not present at all, like some Photoshop heuristic being applied to the world itself.

But the dust can be harvested. It is mentioned in a number of grimoires as a reagent of particular potency (particularly in rites of unmaking or undoing), and there are other texts which report those have consumed it.

Even in the smallest doses, the dust seems quite potent. To its users it presents visions of broken worlds. Of pasts there were not and futures which do not proceed from the present. More disturbingly, the bonds between the consumer and their world are often reported as being stripped away: If they were married, then they were never so. Books they wrote now belong to other authors. In paradox, their parents were never born or they were never born to their parents.

Often shadows of these former truths can be found, but they do not lessen the horror of the loss.

SEEDS

The seed by which many pupating colours come to a new world arrives in the white hot heat of a world flame and does not cool. Its substance is soft, almost plastic in nature. Upon first landing, the seed is possessed of a soft glow, but this fades over the course of a few days.

If heated, the seed produces no occluded gases. It contains no metals. Its substance cannot be identified with terrestrial tests, although it possesses a measurable magnetic field. Although non-volatile, it noticeably shrinks over time. (And even when physically isolated, the seed will continue shrinking while leaving behind no identifiable residue.)

If heated, the seed produces no occluded gases. It contains no metals. Its substance cannot be identified with terrestrial tests, although it possesses a measurable magnetic field. Although non-volatile, it noticeably shrinks over time. (And even when physically isolated, the seed will continue shrinking while leaving behind no identifiable residue.)

The seed is a solidified extrusion into our three-dimensional torpology. It protects the memetic neutrality of the nascent colour so that it neither interferes with the memetic structure of the parental colour (or colours?) nor is corrupted by it. (The pupating colour, thus, is a clean slate ready to have impressions made upon it by the world.)

It is possible that the payload launched by a pupating colour is the seed itself (or a pod of such seeds). But it seems more likely that the colour’s seeds are created in extraterrestrial environments of which we could only fancy: Forged in depths of a gas giant? Skimmed from the surface of a neutron star? Scooped from the thin, memetic vacuum of an Oort Cloud?

These are mysteries which shall light our eyes with impossible hues only when we have journeyed deep into the voids of space.