In “(Re)-Running the Megadungeon” I talked about how to keep a dungeon complex fresh by restocking the room key and using wandering monster tables as a form of low-tech procedural content generation. In “Wandering Adventures” I talked about how the OD&D wandering monster tables could be used to generate entire adventures. Now I want to build on those ideas by touching on the basic concept of factions in the dungeon.

In “(Re)-Running the Megadungeon” I talked about how to keep a dungeon complex fresh by restocking the room key and using wandering monster tables as a form of low-tech procedural content generation. In “Wandering Adventures” I talked about how the OD&D wandering monster tables could be used to generate entire adventures. Now I want to build on those ideas by touching on the basic concept of factions in the dungeon.

To immediately boil the idea down to its core: If your dungeon has a life beyond the activities of the PCs, it is much easier to revitalize the dungeon between delves. The life of the dungeon will naturally generate the ideas necessary to restock the dungeon (and, thus, carry a lot of the weight for you). This becomes even easier if the dungeon contains multiple, independent factions. (And even moreso if these factions are openly hostile to each other.)

Nor does this have to be something that you need heavily pre-plan. It can largely just be a matter of keeping one eye on it during your restocking process: “Okay, the PCs killed 70% of the orc population on Level 3. Who can take advantage of that? What will the Orc King’s response be? Actually, wait, they killed the Orc King. Have the orcs broken into factions? Could the Red Prince (I just made that name up) have allied with the goblins on Level 2 to push his claims? How will the other orcs feel about being asked to co-exist with lowly goblins? Will they turn to the Voodoo Necromancer (just made that up, too) who was once the Orc King’s advisor?” That’s about 15 seconds of brain-storming. Follow it up with a couple minutes of actual prep and you’ve got orc-and-goblin warbands with faces painted bright crimson squaring off against orc warriors ‘roided out on alchemical strength-boosters wearing the bone fetishes of the Voodoo Necromancer. It doesn’t even really matter if the PCs get involved in the actual politics of the situation: Even if they just hack their way through these orcish factions, they’ll (a) recognize that the dungeon has changed in their absence and (b) get some unique and interesting hacking out of it.

(You can see a similar real-play example of this in Delve Seven of “(Re-)Running the Megadungeon” when the elementalist gets killed.)

So, obviously, there’s nothing wrong with winging it. In the process of winging it, however, I’ve found it generally useful to prep two key pieces of information:

- Identify each faction.

- Identify the territory controlled by each faction.

Most of the time, it’s not necessary to get really obsessive with this. For example, in the Caverns of Thracia I don’t really have much more than a general sense that “the cultists control this chunk of the map”, “the lizardmen control these rooms”, “the anubians are based out of this complex”, and the like.

My understanding of the complex is fairly amorphous, and putting more detail into it is probably counter-productive: It’s unlikely to ever be noticed by players, it’ll bog down your prep, and it’s rarely representative of the fairly amorphous nature of contested territory. Precision will also tend to bog down your ability to flexibly interpret the results from your random encounter tables.

(Of course, if you’re designing a scenario in which particular focus or importance is placed on factional play, more detail may be merited.)

RANDOM FACTION INTERACTION TABLES

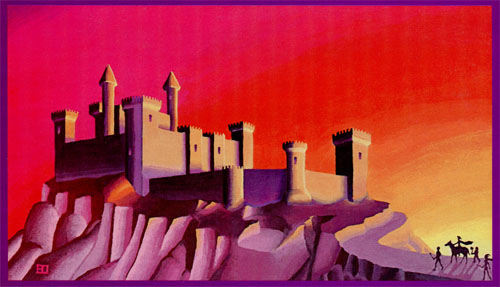

With that being said, it might be valuable to build some quick, light tools that will allow you to procedurally generate the ebbing shifts of factional fortunes in the dungeon. For this purpose, let’s turn to the Caves of Chaos from the classic B2 Keep on the Borderlands.

For those unfamiliar with this module, the Caves of Chaos are particularly useful for this purpose because they’ve already been conveniently split into factions: Essentially you’ve got a small valley full of caves, with each cave leading to an interconnected system of caverns and serving as the lair for one of several chaotic factions. The factions are:

(“Wandering Adventurers” refers to an NPC party entering the Caves of Chaos.)

FACTION CONFLICT CHECK: After each visit to the caves by a party of PCs, make a faction conflict check. Roll 1d6. On a roll of 6, conflict has broken out between the factions. Roll twice on the faction table to determine which two factions have come into conflict. (If you roll the same number twice, either re-roll or assume some sort of civil strife.) Then roll on the Conflict Resolution Table:

Stalemate Skirmish: The factions are largely unaffected by the conflict. Their forces may have been reinforced, or you may wish to subtract 1 or 2 members from one of their encounters. (The conflict may leave them ripe for alliances against their recent foes; or leave a chamber showing recent signs of conflict; or a couple of corpses tossed onto the valley floor to be feasted on by the owlbear.)

Faction Damaged: A damaged faction has suffered losses equal to roughly 25% of their strength. Subtract 1d4 members from each encounter (keyed or random) with that faction.

Faction Crippled: A crippled faction has suffered loses equal to roughly 50% of their strength. Eliminate entire encounters or subtract 1d12 members from each encounter (keyed or random) with that faction.

Faction Destroyed: A destroyed faction has been eliminated. Their lair may lie empty, be occupied by the other faction involved in the conflict, or restocked randomly. Their population has been killed, driven off, or enslaved.

Factions Unite: The two factions have allied with each other. (One of the leaders may have been killed. The alliance may be for some short-term goal. Or the populations might be fully intermixed between the lairs.)

USING THE TABLES

Like a random encounter table, the output here is designed to be flexibly interpreted. Once again, the Caves of Chaos are great for this sort of thing because it already includes some short notes regarding the relationships between the factions. (For example, the owlbear is described as having recently munched on some gnolls. The two orc chieftains have a secret meeting room that only they know about. And so forth.)

Mostly for the fun of it, I’m going to roll up a couple actual examples using these tables. We’ll start by assuming that I’ve just rolled a “6” on my Faction Conflict Check and go from there:

1. DETERMINE FACTIONS: I roll 1d12 twice, generating 9 and 5. That’s the Minotaur and the Ogre.

2. DETERMINE OUTCOME: I roll 1d8 and get 8. That’s Factions Unite.

3. INTERPRET RESULT: The Minotaur and the Ogre are the two solo factions in the Caves. (There’s only one Ogre and one Minotaur.) Scanning their entries, I see that the ogre is willing to sell his services to the highest bidder and the minotaur has a lot of money. So let’s say that the minotaur has hired the ogre for some purpose. What could it be? Well, the minotaur is willing to help the bugbears if they pay him in slaves. What if the bugbears cheated the minotaur and now he wants a little help to get the payment he feels is his due? That sets up a scenario where the PCs could arrive in the valley to see bugbears fleeing from their caves; or find bugbears shackled in the minotaur caverns; or just the minotaur and ogre huddling up in the minotaur’s cavern while they plot the glories of their revenge.

Let’s do it again:

1. DETERMINE FACTIONS: I roll 4 and 12. That’s Goblins and Wandering Adventurers.

2. DETERMINE OUTCOME: I roll a 5 for Both Factions Damaged.

3. INTERPRET RESULT: This one is pretty easy to figure out. A group of adventurers entered the goblin caverns, wreaked some havoc, and then got driven off.

4. GOBLIN ENCOUNTERS: There are 36 goblins total in this lair. A 25% loss would represent 9 goblins. I can represent this loss pretty easily be eliminating the wandering patrol of 6 goblins (the surviving goblins have bunkered down) and the 4 goblins guarding the store room.

5. ADVENTURERS: Where’d they go? Well, let’s say it was a party of 4 adventurers. One of them is dead and his corpse can be seen on a spike outside the goblins’ lair. The rest are either (a) camping nearby and looking for allies; (b) sold to the hobgoblin slavers; or (c) both.

FINAL THOUGHTS

It should be pretty easy to see how this simple system can be used to add a little quick spice to the complex between PC visitations. Combined with the ability to simply use some generic wandering monster tables to rapidly determine the new inhabitants of any lair complex emptied out by the PCs, it’s pretty easy to see how the Caves of Chaos could be easily used pretty much endlessly for low-level adventuring.

“Forge of Fury” is another great example of using factions. I think your system is light and flexible and interesting, thank you for sharing it.

I am expanding my group’s “dungeon crawling.” This web site is a great inspiration for that effort. I also often interpret and adapt material from a random generator, as a great challenge. http://donjon.bin.sh/d20/dungeon/. Making up context for random organization and population leads me to ideas I would not have had on my own, and is rewarding.

It seems that my group takes about 30-40 minutes of real time per room on average. That includes deciding where to go, taking precautions like checking for traps, getting into fights, searching the environment, looting, resting, interrogating prisoners, analyzing information they’ve gotten so far, consulting their map, and the like. They might blaze through a few empty rooms at 3-5 minutes each, then get in a big fight or a disagreement about what to do next that takes up more time; I mean on average.

Having more players slows things down a bit, and being in a new genre and sometimes playing with new people can slow it down a bit. And they are getting to know new characters. I expect this will speed up.

Still, it has informed my plan. No longer do I look at a full page map and figure that’s a 5 hour session. I know it takes more time.

In my context, having factions and ways for them to clash and spark new content is very useful. I appreciate your ongoing essays on the matter.

When it comes to mapping, do you map out the entire setting and then set factions in blocks, or not even address those areas until the party gets within striking distance? I would think the demands of jacquaying would require the entire complex to be mapped. In that case, do you do room keys for every area? With factions, that means a territory might change hands several times and have the remnants of those ownerships present, invisibly in the DM’s prep, several times before the characters even see the place.

Or, do you use continuity as an interpretive lens for deciding how to describe what happened, and leave it flexible and adapt results as characters get close?

I could see fleshing out the overall threats in an area, then adding to and taking away from that list over time. I could also see identifying “that sort of monster in this faction” and letting the dice and needs flesh things out. The main danger is keeping track of continuity there; if the bugbears have had a pack of riding raptors all along, why are we just now seeing them? Interpreting random generated material can provide the impetus to make creative answers that lead to interesting adventures, so I’d lean in the improvised direction.

Other thoughts.

I think 7 should not be “both factions destroyed” but instead “both factions relocate or expand.” That way you can have a faction go away (or be destroyed) and you also have a provision for one group to move into another group’s base territory. And if you roll one faction twice, then roll that they relocate or expand, they can move into an empty area, or be joined by more and fill out another area.

It is worth pointing out that randomization is between a coin toss (1d2) and percentile; the faction list can be of many different lengths, as long as it is easily randomized. That includes putting big factions on more than once, or having an “internal strife” and an “environmental hazard” option for factions that may face both of those threats.

Factions may be well served to have sub-faction listings. These can either be factions within the faction, or local threats factions face. That way, if you roll the faction twice, they can suffer from internal strife or local hazards that are not powerful enough to be factions. That could be ad hoc randomized, or decided.

If you rolled the faction (internal) and another group, one of the factions in the group would clash with another faction. If you rolled the faction (local hazards) then another faction could tangle with some of the local color around another faction. It’s a way to have factions face threats without making each threat a faction.

For example, from Khundrakar. The faction list could look like this:

1. Mountain Door Orcs.

a. Yarrick, orc chief. Burdug, orc shaman. Great Ulfe, ogre leader.

2. Trog Clan.

a. Captive bear. Mold chamber. Gricks.

3. Duregaur.

a. Allip. Boobytrap malfunction. Smithy mishap.

4. Stirge.

a. Rolling this twice triples their numbers and triggers another nest.

5. Dragon.

a. Rolling this twice, re-roll.

The sinkhole area has some threats and obstacles, but no real factions. So if a faction relocated, they could move into the sinkhole area, in addition to existing ambient threats.

Also, the sub-table could have an option between civil strife as one threat, or external as another threat. There are various ways to do this with some ease, I think.

As an example, rolling 1d10/2 twice, you could get 3 twice. Then you could see that there is an allip, boobytraps, and smithy; you could roll 1d6/2 and get allip. So your result is the duregar had a fracas with the allip. Rolling a 2, it seems the duregar lose 25% because of ongoing allip confrontations. Or if you rolled an 8, knowing alliance is not possible, you could determine the allip is now incorporated into duregar defenses; they leave an area alone and trust the allip to sort out intruders. Something like that.

Thanks again for a great series.

There is a way to make this useful beyond the mega dungeon concept. If there are regional factions, then a convenient lair location could be restocked or have clashes with other forces in the area.

For example, a ruined temple with only 2 levels could be in a region with a chart like this:

1. Bandit slavers.

2. Revolutionary Necromancer.

3. Giant vermin.

4. Trolls.

5. Goblin bandits (already in the temple).

6. Minotaur leading bugbears (already in the temple.)

That way, you could generate faction conflict with groups not in the lair, but groups that would possibly like to be in the lair. Or you could simulate those in the lair clashing with outside parties besides the characters.

Lot of good thoughts, Andrew. This also works for urban campaigns: If you’ve got multiple active gangs and/or criminal families; or a number of different merchant princes; or several local businesses in competition. Lots of options.

Re: [Xandering]. When building larger dungeon complexes you can sketch out a rough outline of each level (“on that level there are four bane thralls and their thrall armies”) and an idea of how they connect to each other pretty quickly. Then you can fill in the details as the PCs explore.

My rule of thumb: Have the current level and any level they can get to from this level fully prepped.

[…] an OSR blog or two, playing Dungeon World and re-reading an old D&D campaign idea have my head swirling with […]

[…] С оригиналом статьи Вы можете ознакомиться здесь. […]

Excellent stuff. Just fleshing out an urban environment this week for upcoming play, and this is … ahem … right up my alley. There are five major gangs in the city whose turfs I have mapped, but having a table or two to help decide what happens, let’s say every week or month, between them is great! This is aside from a calendar with some other gang-related events, of course.

[…] seem intimidating (or at the very least, time consuming. The Alexandriansolves this with its post “Keep on the Borderlands: Factions in the Dungeon” which has random tables for determining which factions are fighting one another as well as the […]

[…] disputes and infightings might as well be covered by The Alexandrian’s faction interaction table. If someone smarter than me has made something that covers a particular niche, why not use […]

[…] have also been using the faction development ideas from the Alexandrian. The article itself is technically a meditation on how to do this for whatever […]