I’ve just had an interesting discussion regarding the intersection between random generators and railroads.

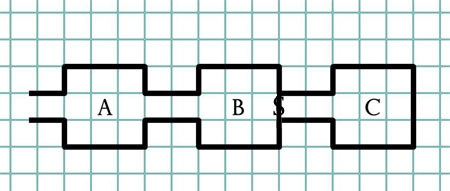

Hypothetical Situation #1: You’re running a standard hexcrawl campaign. You generate a sequence of six locations. Regardless of where the PCs decide to go, they will encounter those six locations in the order that you prepared them.

This is self-evidently a railroad.

Now, take this hypothetical situation and begin stripping off locations until you’re left with a single location. Regardless of which direction the PCs leave town, they will encounter that specific location.

Still self-evidently a railroad.

Hypothetical Situation #2: You’re running a standard hexcrawl campaign. You create a random encounter table of six locations. When the PCs leave town, you start rolling on the random encounter table. As they encounter locations you cross them off the random encounter table. Since they’re randomly generated, however, the sequence in which they’re encountered may vary.

Is that a railroad?

Does your answer change if I similarly strip off locations until the random encounter table consists of a single location?

THE CORE DISTINCTION

Does this mean that random content generators are an example of railroading?

No. But this thought experiment does demonstrate the complexity of these issues and the danger of trying to create some sort of “railroading purity test” for various techniques without considering the motivation, context, and methodology of their use.

The core distinction here is whether or not the players are making a meaningful choice. In this hypothetical hexcrawl scenario, the choice of direction has been rendered meaningless (since you’ll have the same experience regardless of which direction you go). And if the choice is meaningless, why are you having the players make it? Why are you lying to them about the choice being meaningful?

Random anecdote time: Many, many moons ago my players needed to explore the sewers beneath a major fantasy metropolis. I didn’t want to map the sewers out and the only game structure I really understood for that sort of thing at the time was dungeoncrawling. So I came up with a system which randomly generated dungeoncrawling maps for the sewer.

This worked just fine and the players were having a great time… until they realized that the terrain was being randomly generated. Their interest in exploring the sewers instantly evaporated: They knew that their choices were irrelevant. There was nothing that could actually be discovered. They were using a game structure of exploration, but they weren’t actually exploring anything.

This taught me a really important lesson as a GM: In order for an exploration scenario to work, there has to actually be something to explore. If all choices are equally likely to get you to your goal (because your discoveries are being randomly generated or because the GM has predetermined their sequence), then your choices become meaningless. And meaningless choices are boring and frustrating.

MAKING CHOICE MEANINGFUL

I’ve talked frequently in the past about the usefulness of procedural content generators: In a dungeon, random encounters can simulate the activity of a complex. In open campaigns, dungeons can be restocked with random generators. In hexcrawls, random generators can simulate the activity of the wilderness or they can be used to generate new locations on-the-fly.

These tools are incredibly useful. But how do you use them in a way that doesn’t negate player choice? How do you use them without the railroad?

The solution is actually quite obvious: Make sure the players’ choices are still meaningful even with the presence of the random elements.

A really simple example of this is simply allowing the actions taken by the PCs to affect the random generators: In a dungeon, for example, certain activities will create noise and increase the likelihood or frequency of encounters. In a hexcrawl, choosing to go to the Old Woods will cause the GM to roll on a different random encounter table than the Volcanic Peaks. And so forth.

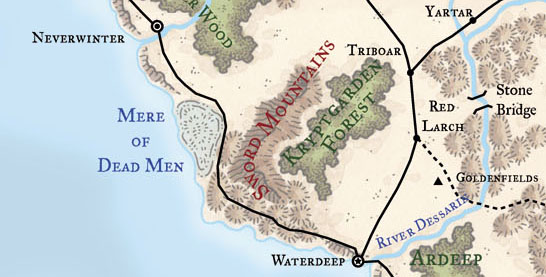

Another straight-forward variation, in the context of an exploration scenario, is to create an environment with enough meaningful detail that it renders choice meaningful while the random content provides an additional patina of variety. For example, for my OD&D open table hexcrawl I keyed specific content to 256 hexes. That pre-existing geography creates a ton of meaningful choice: The random encounters that are being generated on top of it simply provide additional spice. Another example is the dungeon complex where the keyed rooms provide the meaningful choices, while the random encounter table provides a variety of activity throughout the complex.

A more complex variation would be a procedural content generator that creates an environment as the PCs explore it. This only works, however, if the location at which a piece of content is encountered becomes meaningful. This rules out purely ephemeral encounters (you meet eight orcs and you kill them) because the location is meaningless. But if the PCs are heading west and discover that the Salt Flats of Doom are over there and that Castle Vampire is on the far side of that difficult-to-traverse terrain, that geographical placement becomes meaningful if/when the PCs start mounting expeditions to Castle Vampire. (You could also imagine a structure where placing Castle Vampire and the Valley of the Giants next to each other creates a unique alliance that wouldn’t occur if it turns out that the Valley of Giants is on the other side of town.) The ability to revisit and reincorporate content, as is so often the case, is the key factor here.

Let’s consider a non-exploration example: In Technoir, the plot map of the scenario is randomly generated by the GM through play. Both the GM and the players discover the truth of the conspiracy together. However, before the players make any decisions the GM creates the mission seed which forms the core of the conspiracy. The mission seed provides the pre-existing detail which makes choices meaningful as the PCs seek to unravel the conspiracy (and, usually, penetrate to the heart of the mission seed). Even though the outcomes of these decisions are random, the choices remain meaningful because (a) they determine how the random elements connect to the mission seed (even as they also continue to redefine the conspiracy as a whole) and (b) the mission seed itself is a hard truth which can actually be discovered.

There are a lot of other ways in which random generators could be rooted into meaningful choice (or surrounded by it) without losing their utility. (And we would doubtlessly discover even more if we started poking around other game structures.) What you’ll note, however, is that all of these techiques are very different from simply taking the encounter you want the PCs to have and putting it in front of them regardless of which choices they make.