MAPS

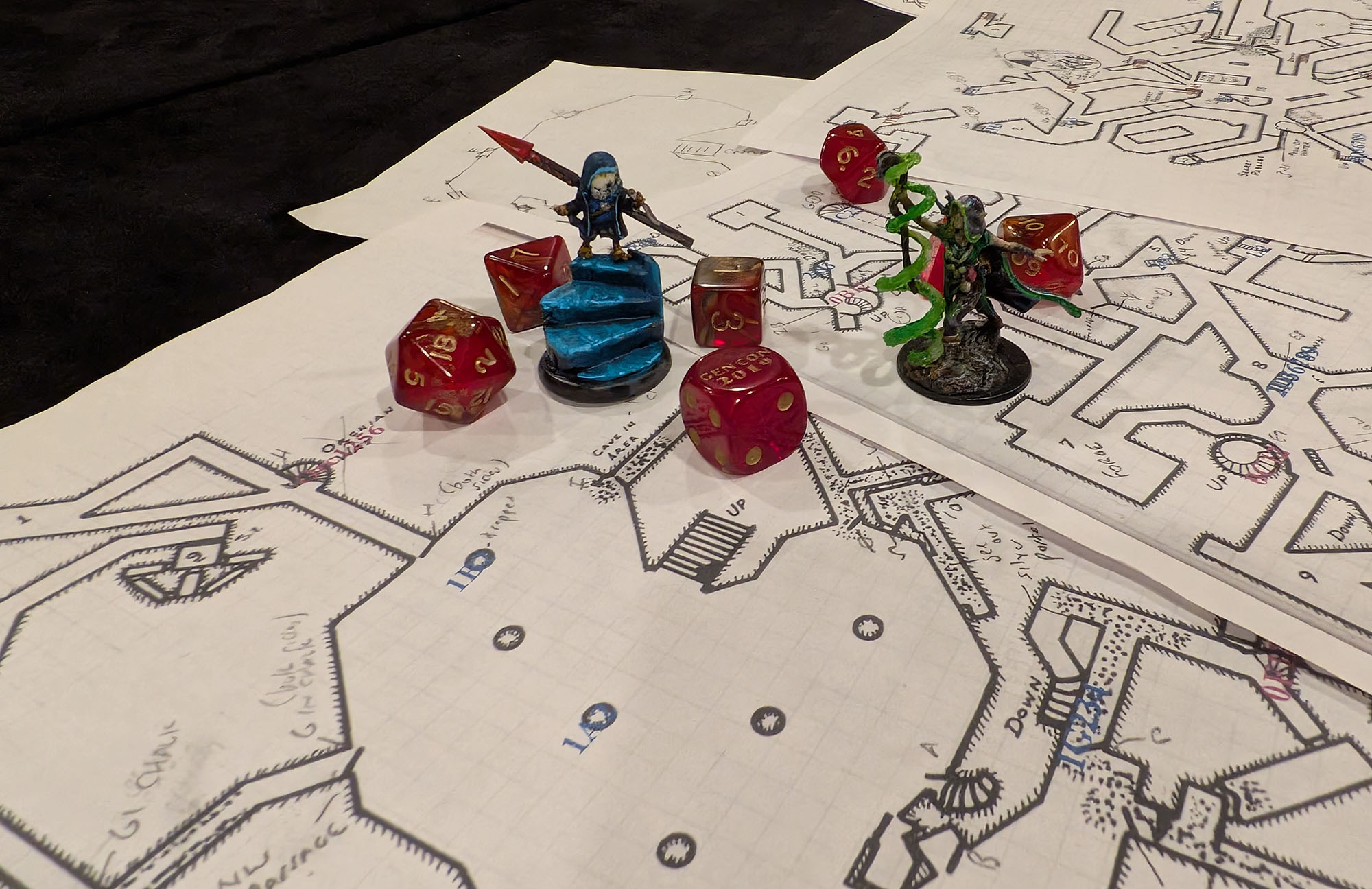

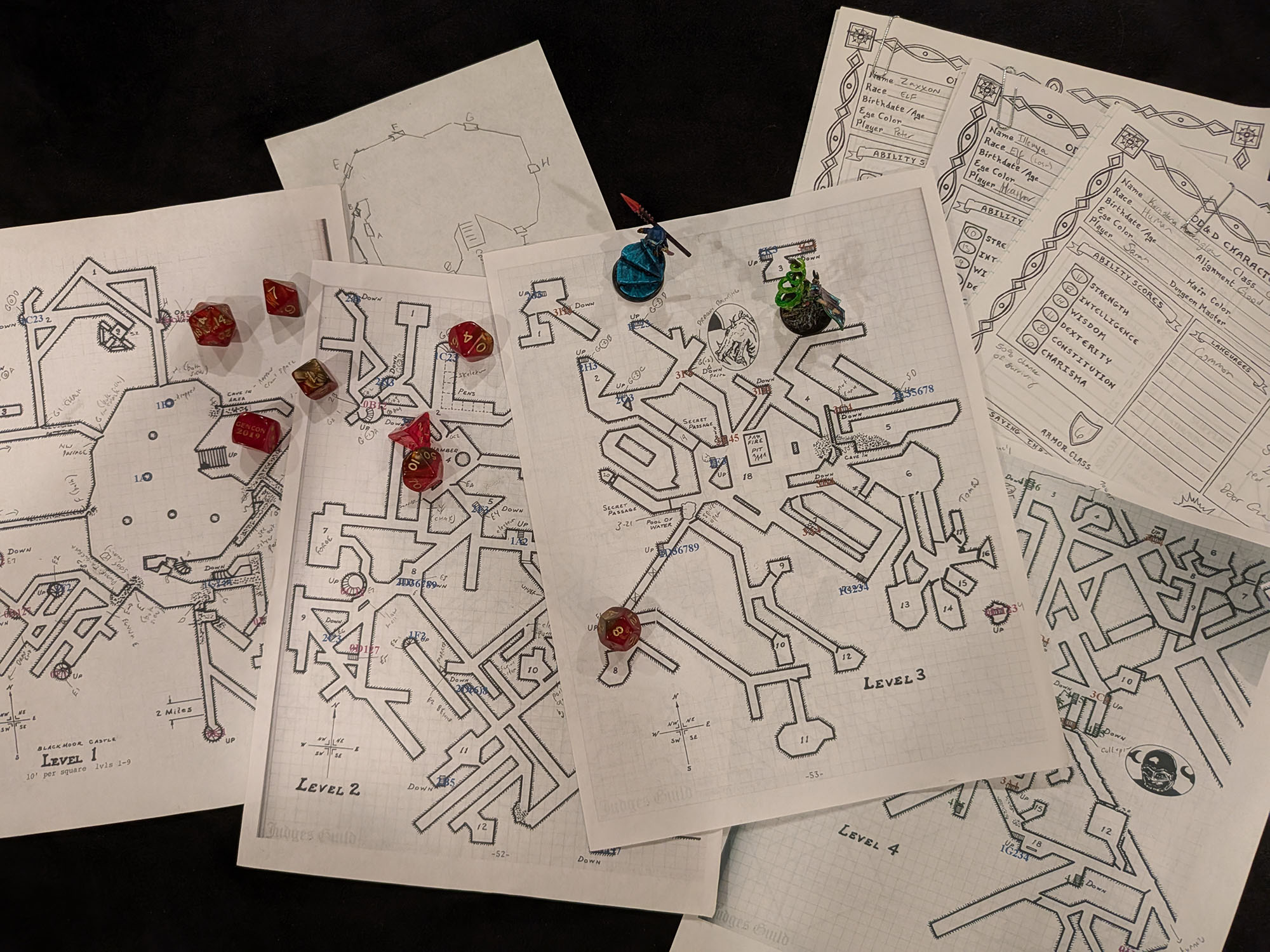

Arneson’s maps for the Castle Blackmoor dungeons are simply fabulous. I’ve previously discussed how incredible the first room of the dungeon is, as well as the terrors of Tanglefuck, but all of the levels are deliciously labyrinthine and intricately xandered. Of particular note is Arneson’s heavy use of diagonal tunnels, which are surprisingly effective at confusing the players’ spatial intuition.

When you reflect that, with these maps, Arneson was doing something that no one else had ever done before, the fact that they nevertheless stand the test of time and still create a completely compelling dungeon experience is a jaw-dropping accomplishment. Blackmoor is, in my opinion, a timeless classic.

In terms of utility, though, the biggest obstacle to using the Blackmoor maps are the unkeyed staircases. There are A LOT of them (which is good), but:

- there is no indication of where each staircase goes;

- staircases can attach to multiple levels; and

- staircases can skip multiple levels before reaching their destination.

For example, consider this section of Level 5:

Figuring out where all these stairs connect is made even more difficult because the maps for different dungeon levels are done at different scales (to accommodate larger levels that otherwise wouldn’t conveniently fit on a single page).

Basically, if you jump into Castle Blackmoor without predetermining how the stairs connect to each other, you’re going to end up slamming your face into the wall in the middle of the session trying to figure it out. Fortunately, DH Boggs at Hidden in Shadows has done a bunch of work on this issue, which you can find at Aligning the Stairs, Shafts, and Elevators in Blackmoor Dungeon.

The other thing to note about the Blackmoor dungeon is the lack of a room key. I pulled a few details from tales told of the infamous dungeon, but mostly I just improvised my descriptions. One of the cool things about the campaign was the way in which improvised details would become unexpected poles of adventure, but my notekeeping system wasn’t designed to record these details. As a result, the dungeon was really “living in my head,” and when COVID created a long break in the campaign and the dungeon was no longer being refreshed in my imagination each week, it fell apart.

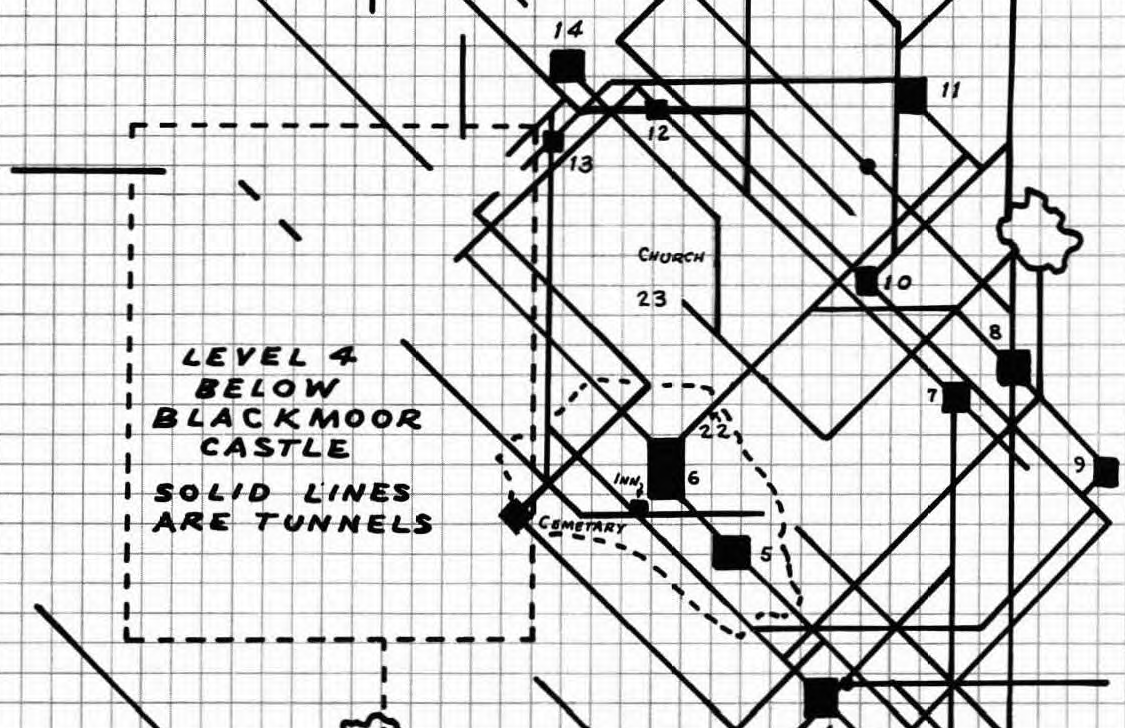

Another challenge or crux to be solved when using the Blackmoor dungeons are the tunnel maps. Levels 4 and 5 of the dungeons connect to a much larger network of underground tunnels that run underneath the town and nearby area. Here’s a sample of what these maps look like:

The rectangular dotted line indicates where the Level 4 Dungeon map would “fit” on the tunnel map. What the oblong-shaped set of dotted lines indicates is unclear, but you can also see indications given for where these tunnels connect to the Cemetery, Inn, and Church as seen on the Blackmoor Village Map. Additional areas intersected by the tunnels are indicated, but completely unkeyed in The First Fantasy Campaign.

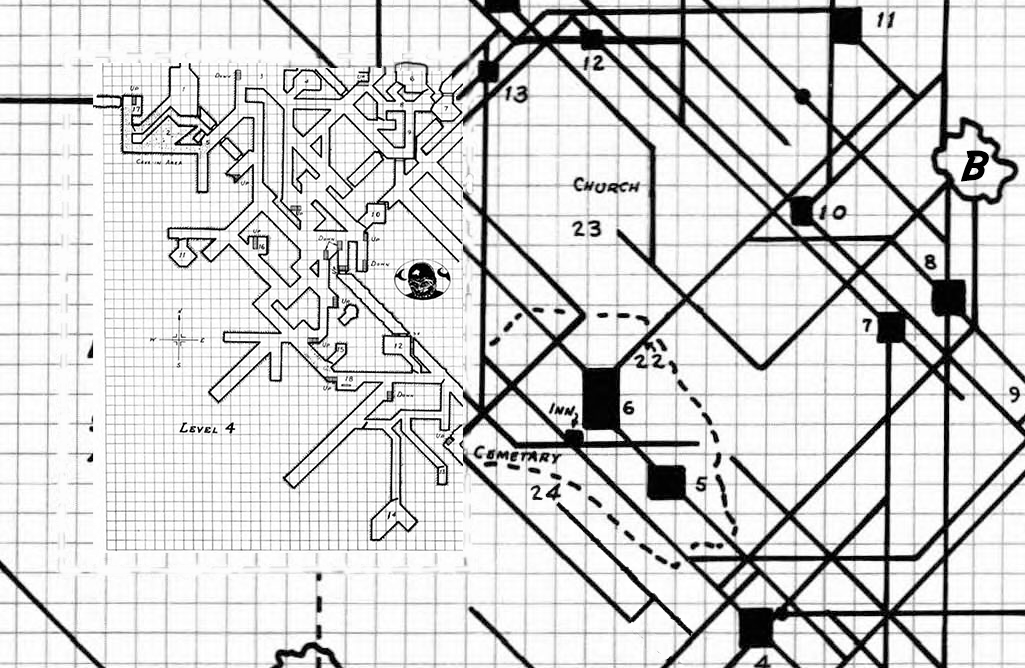

To deal with this, I started by prepping a version of the Level 4 Tunnel Map that included the Level 4 Dungeon Map:

(This was not necessary for the Level 5 Tunnel Map because there are fewer and less complicated connections to the Level 5 Dungeon Map. Although it’s useful to note that the Level 4 and Level 5 tunnels sometimes intersect the same subterranean areas.)

The next question was figuring out what the various numbered areas were. I decided to grab a couple dozen Dyson Logos maps, stock them with my Arnesonian stocking procedures, and drop them in. This was really fun, and one of my big regrets with the campaign is that my players didn’t do much more than dip their toes into these tunnels.

A final crux was how to handling the stocking of huge number of denizens. Basically, if you use the 1974 D&D rules for randomly generating the number of creatures appearing, you can end up with stuff like 17 ents, 76 dwarves, or 23 hobbits keyed to 10’ x 20’ room. This “horde in a small room” is also a problem with Arneson’s published key — which, for example, includes 32 dwarves in a 5’ x 10’ room — and it’s entirely clear what his intention was or how that would be handled at the table.

I saw basically three options:

- Revise the # appearing to some reasonable count based on the size of the dungeon.

- If it makes sense, spread the creatures out through several neighboring rooms.

- If the stocking procedures indicated an impossible number of creatures in a room, treat the room as the entry point to a sub-level that could t hen be stocked with the indicated creatures.

I wanted to use the original stocking procedures as my guiding light as much as possible, so I discarded #1. I did a little bit of #2 where appropriate, but I generally found #3 the most interesting option.

So I once again grabbed a bunch of Dyson Logos maps. In this case, though, I just stuck the blank maps into a folder labeled “Sub-Levels.” When the PCs reached a location that required a sub-level, I would grab a map semi-randomly from the folder and slot it in.

My seed key for the Blackmoor Dungeons, by chance, mostly had these sub-levels generated on the lower levels, so I ended up only developing two or three of these in actual play. But it was a fun way to make the Blackmoor Dungeons my own, and the mixture of Dyson’s mapping with Arneson’s was an interesting change of pace.

ENCOUNTER DIE

In my Blackmoor campaign I also used an encounter die mechanic, as detailed in the Blackmoor Player’s Reference. This was not an Arnesonian technique, but something I adapted from OSR mechanics, most notably Courtney Solomon’s hazard die.

The basic concept is that, instead of rolling 1d6 per turn and generating a random encounter on a roll of 1, you roll 1d6 per turn and each die result has a different effect:

- Encounter

- Monster Sign

- Torches Burn

- Torches & Lanterns Burn

- Rest

- Dungeon Effect / Trap

The idea is that this eliminates a bunch of timekeeping activities, instead loading everything onto a single die roll that you were going to make anyway.

My verdict?

It sucked.

Because something is always happening, every dungeon turn got bogged down in some random bookkeeping. It was a mood- and pace-killing source of constant annoyance.

I ended up dropping the system entirely after a few sessions, and I don’t recommend it.

GROUP VENTURES

Fairly early in the campaign, due to a confluence of events, a group of PCs ended up taking over the local church in Blackmoor. This created an unexpected group venture, and managing that group venture in an open table created logistical issues for which I didn’t find a satisfactory solution before the campaign ended.

The problem, in short, was that there was church-related development and church-related adventures that these PCs wanted to pursue. But because they were all in it together, they wanted to resolve these activities only when they were playing together.

Additional complications were added because some of the activities they wanted to pursue — throwing a big festival to celebrate the rededication of the church; proselytizing to other communities around Blackmoor — both required special prep from me and also had a wide impact on the entirety of Blackmoor.

The result was this tight nugget of activity in bespoke sessions that could also create a weird pattern of lockouts in the rest of the open table. It probably would have worked out OK if these three players had ben able to get together on a regular basis, but there were A LOT of scheduling problems and cancellations. (Which were then further complicated by the COVID pandemic and lockdowns.)

As I say, this is a problem did not actually solve before the campaign came to an end. But figuring out how to handle group ventures like this in the future is definitely on my To Do list for future open tables.

FURTHER READING

Reactions to OD&D: The Arnesonian Dungeon

Reactions to OD&D: Arneson’s Machines