IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

SESSION 8B: A NEW COMPANION

October 7th, 2007

The 24th Day of Amseyl in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

MEETING TOR

The five of them moved into the common room of the Ghostly Minstrel. It was sparsely populated in that early hour of the morning, and Tellith pointed them towards a short, stocky man with light brown hair who was sitting at one of the tables and reading a slim book by the light pouring through the front windows.

When he saw them approaching, the man rose and they saw that he was ever-so-slightly bow-legged. “My name’s Tor.”

After a few moments of conversation, it quickly became apparent that Tor thought they were expecting his arrival. None of them had any memory of that, of course, but they managed to hide that fact from Tor.

It turned out that Tor was carrying a letter of introduction from a man named Ritharius. But, as was clear from the letter, Tor did not actually know Ritharius – had not, in fact, ever met the man.

The amnesiacs had hoped that, by careful questioning, they might find out why Tor had been sent for, and in that manner discover what their intentions had been during the time of their memory loss. But, unfortunately, Tor’s interests were maddeningly vague – he had been interested in pursuring the life of a wandering errant, hoping to accrue those deeds of valor which might allow him to become a knight.

The group told Tor a little of what they were currently planning – in very general terms – and he seemed more than happy to help them. A firm handshake from Agnarr seemed to seal the arrangement.

Agnarr, Dominic, Elestra, Ranthir, and Tee were still bedraggled from their morning excursions in the sea. And there was various business to attend to. So they agreed to go their separate ways for a bit, and then reconvene here in the common room in the early hours of the afternoon.

While the rest of the group headed upstairs to get cleaned up, Tor arranged a room for himself and lodging for his horse (paying for a week in advance). Then he headed across Delver’s Square and headed down into the Undermarket. There he sought out the Delver’s Guild facilities and arranged membership with the ebullient Gorti. With his papers and his lodgings in order, Tor spent some time wandering through Midtown. He was amazed by the size and wealth of this city, and his eyes were drawn constantly back to the wonder of the Spire.

After finding what high quality barding would cost for his horse, Blue, Tor returned to the Ghostly Minstrel’s common room and continued reading. Ranthir, who had spent this time studying his arcane lore, greeted him as he passed through on his way to the Delver’s Guild library, where he researched the Order of the Chalice. Although he found some generally unsatisfying tidbits of information about the Order, he found nothing to explain what connection – if any – had existed between the group, Sir Robilard, and the mysterious Ritharius.

Elestra, meanwhile, had gone on another walkabout. She was increasingly convinced that the Voice of this strange city was whispering in a place just beyond her hearing. And more and more it seemed to her not as if she was trying to hear the voice of a stranger, but that it was the voice of a long-lost friend.

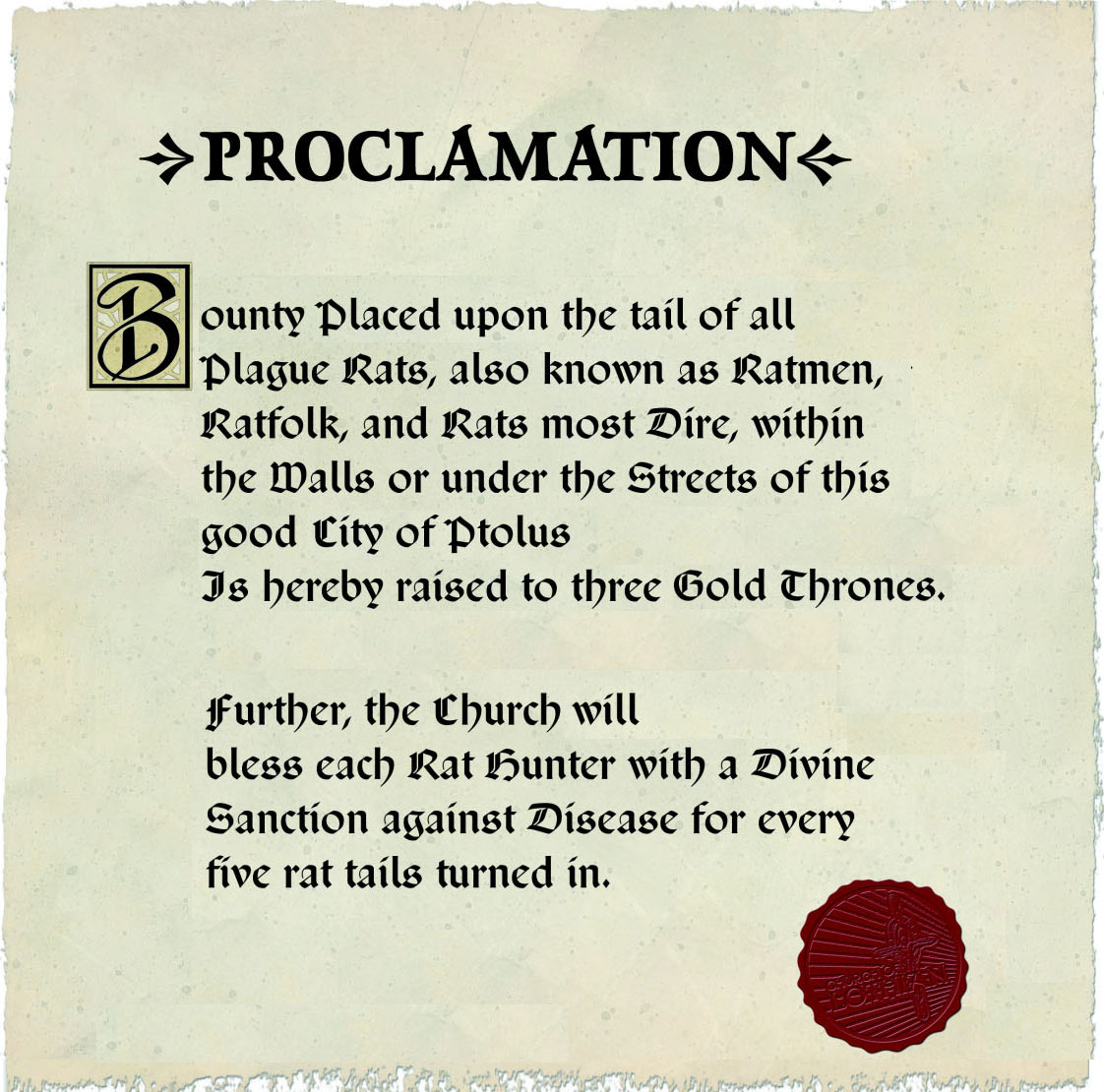

In the end, Elestra did not hear the Voice as clearly as she might have hoped. But its whispers – half heard and barely understood – were beginning to guide her. In more practical terms, she discovered that the Commissar had placed a bounty upon the “tail of all Plague Rats, also known as Ratmen, Ratfolk, and Rats most Dire”. Notices were being posted throughout the city. Elestra grabbed one of them and brought it back to the Ghostly Minstrel.

The rest of the group, but particularly Agnarr, thought that the rat bounty sounded like a great opportunity to earn a little coin. They agreed that, in the morning, they should investigate the best ways of pursuing the matter.

LINECH’S OFFICE

(08/25/790)

In the morning, after breakfast, Dominic went to the Temple of Asche and spoke with Mand Scheben and Lord Zavere (by way of the purple stone). He reported on everything that had happened the day before. Zavere, in turn, told him that the man with the star-shaped tattoo was Malkeen Balacazar. (Dominic didn’t mention the deal Tee had made, since he didn’t know about it, but he did tell them that the watch was most likely in the hands of the Balacazars.)Dominic also talked to Mand and Zavere about Tor and the letter of introduction from Ritharius. To Lord Zavere’s questioning, he reported that none of them had any idea who Ritharius was or why he might be sending Tor to them.

Lord Zavere told Dominic that Ritharius was an “associate” of his. If Tor had come from Ritharius, then Tor could almost certainly be trusted.

Zavere also had another job for them: Linech Cran’s office was protected with anti-scrying spells. Zavere had created a small wooden cube – about the size of a child’s plaything – and imbued it with magicks that would help him to penetrate those defenses. He wanted them to sneak into Linech’s office and hide the cube.

Dominic felt this would be difficult – given the way they had parted company with Linech – but Zavere was offering them 1,200 gp for the job. Dominic said he would have to talk it over with the rest of the group, but agreed to take the scrying cube back with him.

Zavere and Mand paid him a further installment on the money they owed the group for their ongoing activities, and Dominic headed back to the Ghostly Minstrel.

Meanwhile, Tee, Tor, and Elestra were scouring the city to see if they could find a good place to follow-up on the activities of ratmen. They discovered that there had been several sighting of ratmen recently in the area around the Midden Heaps in the Guildsman District.

When everyone had returned to the Ghostly Minstrel, Tee and Elestra made excuses to separate themselves from Tor and met up with Dominic, Agnarr, and Ranthir. Dominic split the money and shared the information he’d gained from Mand and Zavere.

Both Elestra and Tee recognized the name of “Balacazar”: The Balacazar family was the oldest and most powerful criminal organization in Ptolus. Menon Balacazar was the aging head of the organization, but his son – Malkeen – was second in command and well-known for the star-burst tattoo over his right eye. (Menon also had two daughters, Fesamere and Maystra.) Everyone knew they were criminals, but they were “officially” a minor merchant house with a small estate in the Nobles’ Quarter.

The revelation that they had brushed up against the highest echelons of the Balacazar crime family – and that Malkeen might even know their real names – sobered the group immensely.

But there didn’t seem to be much they could actually do about it. What they did decide, after looking at their finances, was that they should take the job from Zavere. They’d also get Tor involved in the new job, but wouldn’t give him much in the way of details from the previous job (most notably, the Balacazar connection). They also decided to continue keeping their shared amnesia a secret from him.

Tor was more than happy to help, and the group split up for a few hours to gather information.

Tee and Elestra asked around town about Linech. They discovered that, shortly after their meeting with him the previous day, he had lowered the gate across the entrance to his burrow and shut himself inside. The word on the street was that he had done something to anger the Balacazars, and had now given up all hope. (“No wonder he was so angry about losing the watch,” Tee said.)

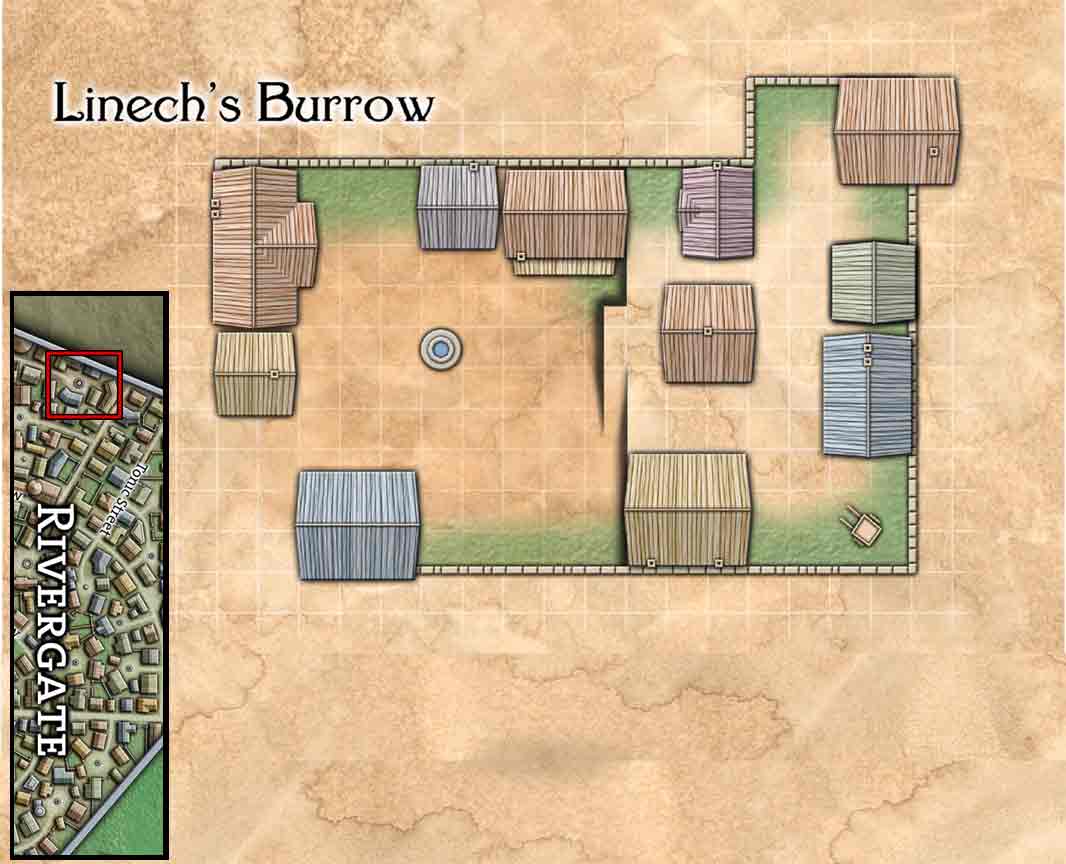

Tor, meanwhile, headed up into the Rivergate District to scout around and see if he could find an approach to Linech’s office. (Since Linech didn’t know him, the group figured he was the safest one to do the work.) What he discovered was that Linech’s burrow was right up against the western wall of the Rivergate District – beyond that wall there was nothing except a huge drop-off into the King’s River Gorge.

Fortunately, the building holding Linech’s office was on the other side of the burrow: The ten-foot wall on that side of the burrow was built up and overlooking another burrow directly to the east. The buildings in this other burrow were all independently owned, with the building directly below Linech’s office owned by the Yebures – a father who worked as an accountant and a mother who stayed at home with their young daughter.

Even better, the window in Linech’s office was east-facing – affording the half-orc a beautiful view all the way down the length of Ptolus, but also making it relatively easy for someone to climb up, enter through the window, and hide the scrying cube somewhere.

Dominic had spent some of this time replenishing their diminished supplies, particularly in the crucial area of healing magic.

Agnarr, meanwhile, had simply been wandering the city. He heard news that an explosion of some sort had happened in the North Market. He headed in that direction and discovered that it was, in fact, an “explosion of shadow” which had left a permanent inky darkness at the top of a tower. Several bodies had apparently been removed from the area of the darkness.

Agnarr wanted to know who the tower belonged to. His first tactic, upon spotting a plaque on the side of the building with some writing on it, was to walk up and try to rip the plaque from the wall. (He figured he could take it back with him and have Ranthir read it to him.) The city watch on duty stopped him from doing that, but simultaneously let slip that the tower belonged to someone named Nycedon. That satisfied him and he headed back to the Ghostly Minstrel.

Upon reconvening, the group decided it would be best to wait until evening – the office was more likely to be empty and they were less likely to be noticed.

So, after dinner, they split into small groups and made their way up towards the burrow next to Linech’s.

Once there, Tee went down the narrow alley between the Yebures’ and the house next door. From there she climbed quietly onto the Yebures’ roof. She had some difficulty climbing the next section of wall up to Linech’s window – falling and cracking her head once – but she eventually secured a grappling hook in the chimney on Linech’s roof, climbed the rope, and then rappelled over to Linech’s window.

The lock on Linech’s window yielded to her thieves’ tools easily enough and she slipped inside, falling to the floor next to the life-size gold statue they had noticed the last time they were in the office.

In looking for a place to hide the scrying cube, Tee’s eyes were naturally drawn to the bookshelves along the room’s north wall. Clearing some of the books away she reached back to place the scrying cube behind them… only to find a crumpled up sheet of paper lying there. She pulled this out, glanced at it, and then stuffed it into her bag. Placing the scrying cube and then carefully replacing the books she had moved, she went back to the window, shut it behind her, and climbed down.

Tee gave the signal that the others, scattered around the lower burrow, could disperse. It had all gone as smoothly as anyone could hope.

On the way back to the Ghostly Minstrel, Dominic stopped by the Temple of Asche to report their success. He was paid the remainder of the monies due them, and was told that Zavere would be in touch with them in the morning.

When Dominic joined the others at the Ghostly Minstrel, arriving only a few minutes after they did, he quickly split the money. Agnarr immediately handed 100 gp of his payment to Tee. “You did most of the work on this venture. You deserve most of the payment.”

Tee thanked him, and then pulled out the crumpled note she had recovered from Linech’s office and showed it to them:

Toridan—

Ruror says you’re still making deals with that old fool Demassac. You need to stop this. I’ve told you before. We can’t trust Demassac. No one can, but us most of all. He’s in close with the Balacazars and we’re none too popular with them at the moment. He’ll stab you in the back in a moment. Or stuff you into one his god-forsaken machines. Keep clear of him.

Big Bro

They didn’t know what it meant, but they resolved to look into it the next day. Then they went down to the common room. Tee was careful to make a big spectacle of herself (she wanted a firm alibi) – buying several rounds for the entire common room and letting Agnarr get completely drunk on her tab.

TEE ON THE TOWN

(08/26/790)

The next morning, Tee woke up early and left the Ghostly Minstrel before the dawn’s light had even begun to halo the Spire.Her first stop was the Temple of Asche. A priest ushered her up to Mand Scheben’s office. The priest looked up as she came in: “Tee! I was just writing you a letter!” He crumpled the paper and shoved it to one side.

Tee asked if the scrying cube was working well. It was. In fact, Mand said they had been scrying through it intermittently even before it had been placed. (Tee reflected that she was glad she had taken cares not to take the cube anywhere particularly private.) They had anticipated leaving the cube in place for some time before taking any action on the information it obtained, but it turned out that immediate action was demanded.

The life-size statue of gold in Linech’s office was, in fact, a friend of Lord Zavere’s: A man by the name of Lord Abbercombe. Lord Abbercombe had, apparently, been turned into a golden golem many years ago. A few months back, however, Abbercombe had simply disappeared. How he had ended up in Linech’s office – and how he had come to apparently be paralyzed – were mysteries. But it was very important that they rescue him. And this had to happen quickly, before Linech decided to melt him down for cash or the Balacazars raided Linech’s burrow, killed the half-orc, and took Abbercombe somewhere that would be even more difficult to extricate him from.

Tee is hesitant to take the job. It would, after all, be much more difficult than simply hiding the scrying box.

“Lord Zavere understands that,” Mand said. “Which is why he’s willing to pay each of you 1,000 gp for completing the job.”

Tee agreed to talk it over with the rest of the group.

Her next stop was Doraedian’s. As she entered the office, Leytha Doraedian looked up: “Tee! I was just writing you a letter!” He crumpled the paper and shoved it to the side.

Doraedian had been writing to Tee to inform her that her training would begin the next day.

Tee was excited, but quickly turned her attention back to the reason she had come: She reported to Doraedian the visions (had they been flashbacks?) she, Ranthir, Dominic, Agnarr, and Elestra had experienced when they had been knocked unconscious (while carefully not going into detail on how that had happened). Doraedian couldn’t give her much help in understanding them, but “any insight, no matter how small might be the one to unravel these riddles”.

Tee returned to the Ghostly Minstrel.

WAITING FOR THE NIGHT TO COME

When the rest of the party came down to breakfast on the morning of the 26th of Amseyl, Tee was waiting for them. She quickly discussed the details of the job Mand Scheben had offered them.

They also discussed their other options: Ranthir was interested in following up on the “shadowy explosion” that Agnarr had told him about. Various errands still needed attending. And many of them showed an interest in returning to the dusty complex of tunnels beneath Greyson House – this time better prepared and better armed. And there was the rat bounty to consider.

They finally decided that, as difficult as getting the statue out of Linech’s office might be, the price was right. It was definitely better coin than they could gain from pursuing the rat bounty and surer coin than what might be found beneath Greyson House.

After putting a plan in place, they decided that evening was the earliest they could hope to get back into Linech’s office. They could only hope that Linech wouldn’t do something desperate today. (If he did, though, they took some comfort in the fact that Zavere would immediately know of it through the scrying cube and could take more decisive action.)

With an empty day ahead of them, Tee and Dominic decided to check up on Phon (who they hadn’t seen for several days now). They stopped by Saches and picked up the shirts that Tee had ordered, but Marta told them that, although Phon wasn’t scheduled to come into work that day, she’d seen her the day before and she seemed fine (although very pregnant!). They headed up to Phon’s house, but there was no answer to their knock.

Agnarr, meanwhile, was yet again looking for a dog to rescue from the streets and train into a loyal companion. While wandering the streets of the Warrens, he actually came across such a stray… but made the mistake of offering it iron rations. The dog, repulsed, growled at him and ran away. Agnarr slumped down on the curb for a long while.

Ranthir spent the day studying another spell from Collus’ spellbook, then – perhaps feeling the close quarters of his room – decided to head over to the library and research the tower where the explosion of darkness had happened. Unfortunately, there didn’t seem to be any meaningful records of Nycedon or his tower. He resolved to check the City Library at his earliest opportunity.

Tor, meanwhile, was already at the City Library. He had finished the book he had been reading, and was eager to find more – always working to improve his literacy.

Of all of them, it was perhaps Elestra alone who was working towards their larger goals. She was following the Breath of the Streets, pursuing the whisper of Demassac Tovarian. And then, for the first time, she heard the Voice of the Wall in Ptolus. It guided her back to Nul’s, the hole-in-the-wall tavern in the Warrens where she and Dominic had gone.

From there the patterns of the Breath were clear, and by noon she had followed it from the Warrens into the Guildsman’s District and back again. She discovered that Demassac Tovarian owned a house in the Warrens, out of which he publicly ran a shabby antiques and curio business.

But, in reality, Demassac ran a trade in used magical items, selling directly to criminals and their ilk – which, based on Linech’s letter, she assumed meant the Balacazars. But lately there were reports that Tovarian was beginning to supply the Pale Dogs gang with high quality magic items, making that group more dangerous than it had been previously.

She also discovered a whisper of a whisper… and it said that Demassac Tovarian had connections to a major underworld figure known as the Surgeon in the Shadows.

It took her another three hours, but Elestra finally managed to eke out a few details on the Surgeon: His real name was Kinion Luth, and – for a price – he would alter his customers in horrid ways while granting them fantastic abilities. But whenever she asked for more than that, mouths shut and whispers stopped.

Elestra returned to the Ghostly Minstrel in the late afternoon. There she met up with the rest of the group. They exchanged notes and headed to the Hammersong Vaults in Oldtown. Each of them rented a separate lockbox and placed many of their valuables in them.

Then, with dusk falling, they set out to rescue a golden statue…