Dragon Heist launches with the PCs being hired by Volothamp Geddarm to find his missing friend Floon Blagmaar. Unfortunately, the scenario structure for this investigation is quite fragile, being formed from long sequences of linear clue-finding. There are also several continuity problems that we’re going to straighten out.

VOLO’S HIRING SPEECH

There are several problems here.

First, if the PCs don’t fight the troll or stirges that emerge from Undermountain, Volo has no reason to hire them. So if the PCs decide that discretion is the better part of valor here, the whole campaign never happens. (This is relatively low risk, but something you might want to give some thought to.)

Second, the adventure oddly claims, “Volo is embarrassed to admit he might have gotten his friend Floon in trouble, and he resists providing all the details of what happened the night Floon disappeared.” That must be some vestige from a previous version of the scenario, because in the published version of the scenario he does, in fact, tell the PCs everything that happened and has absolutely no reason to think he’s responsible for Floon’s disappearance. (Just ignore this continuity error.)

Third, when Volo hires the PCs, his hiring speech sets up a timeline of events which doesn’t line up well with the events described in the rest of the chapter. (According to Volo, Floon was kidnapped by the Zhentarim two nights ago, but “before the interrogation could begin”, the Xanathar Guild kidnapped him from the Zhentarim, and when the PCs arrive at the Xanathar sewer hideout, their interrogation of Floon has just begun. Where did the missing day go?) We’re going to clear this up (and prelude a later clue) with two new chunks of boxed text:

The figure who approached you strokes his mustache, adjusts his floppy hat, and tightens his scarf. “Volothamp Geddarm, chronicler, wizard, and celebrity, at your service. I am most impressed by your derring-do, and the truth is that I fear I have misplaced a friend amid the odious violence which has recently been seizing the streets of this fair city, and I could use your assistance in finding him. You’d be well paid, of course.”

PAYMENT: 100 gp per character, with 10 gp per character up front.

DC 10 Wisdom (Insight): Volo is stretching the truth about how much he can pay immediately. (Currently low on cash, Volo is awaiting royalty payments from Volo’s Guide to Monsters and he’s currently endeavoring to finish Volo’s Guide to Spirits and Specters, for which he is certain receive a handsome advance.)

FLOON: Once the job is taken, Volo identifies his missing friend.

My friend’s name is Floon Blagmaar. He’s got more beauty than brains, but he’s a great drinking companion. Last night he accompanied me to the Skewered Dragon, a dark, bawdy tavern in the Dock Ward. I called it an early night, but Floon remained – drinking and merrymaking.

His wife tracked me down here in the Yawning Portal half an hour ago and told me that Floon never came home last night. This was doubly surprising, as I had not previously been aware that he was married.

Floon is a handsome man in his early thirties with wavy red-blond hair. He is not difficult to pick out of a crowd, however, for he insists on always wearing a gaudy, 6-inch bas relief of a unicorn’s head on a chain of blue pearls around his neck.

(The necklace is a holy symbol of Lurue. It was Floon’s mother’s, but he’ll tell any of a dozen different stories for how he got it.)

TO THE ZHENTARIM WAREHOUSE

Tracking Floon from the Skewered Dragon to the Zhentarim warehouse is restructured as a two-part investigation.

BLOOD IN THE STREETS: Make sure to frame the “Blood in the Streets” incident on the way to the Skewered Dragon.

- Mention that the three men who have been arrested each have a black tattoo of a flying snake (one on the hand, two on their arms).

REVELATION #1: Floon was kidnapped by men with flying black snake tattoos.

- Canvassing the Neighborhood: Several people saw Floon and another man (Renaer) waylaid in front of the Old Xoblob Shop (see Dragon Heist, p. 23). Xoblob the Gnome can describe the attack (see Dragon Heist, p. 24). Searching outside Xoblob’s shop will turn up a gaudy, 6-inch bas relief of a unicorn lying in the gutter (see below).

- Questioning at Skewered Dragon: As the PCs arrive, the evening regulars are probably rolling back in. Several of them will remember Floon and be able to describe how he drank with Volo, Volo left, and then he was joined by another man, a “spoiled, rich noble who likes to rub our noses in it!” (Note: Berca, the bartender, knows that the other man was Renaer Neverember, the son of Waterdeep’s previous Open Lord, Dagult Neverember, but she won’t be free with that information.) Floon and the other man left around midnight. They were followed out by several men, one of whom had a tattoo of a flying black snake on his neck.

(Note: Contrary to the published scenario, the patrons of the Skewered Dragon do NOT know that the “flying black snake” men can be found on Candle Lane. Some of them may be able to identify them as Zhentarim gangsters at the GM’s discretion.)

REVELATION #2: Floon was taken to the Zhentarim warehouse on Candle Lane.

- Canvassing the Neighborhood (Looking for Tattoos): Several locals have seen men with flying black snake tattoos “up by the candle on Candle Lane” (see Dragon Heist, p. 24). Surveying the lane identifies the correct warehouse because it had a black winged snake painted above the front door’s handle. Asking workers at the other warehouses along Candle Lane can also point them at the right warehouse, and may also reveal that there was some kind of “ruckus” over there early this morning, with large groups of people coming and going.

- Questioning the Prisoners: The PCs may backtrack to the “Blood in the Streets” crime scene and figure out a way to talk to the Zhentarim agents being held by the city watch. (They’re likely to speak with Captain Staget, see Dragon Heist, p. 27). If they can convince these agents to talk, they’ll learn that they aren’t local, but were told to report to the warehouse as a safe haven after performing the hit on the Xanatharians.

- Tracking Floon’s Beads: Floon kept his wits about him as he and Renaer were being kidnaped. Breaking the necklace around his neck, he let the blue beads drop into the streets and alleys as they were carried to the warehouse. PCs who find the unicorn’s head in the street outside Xoblob’s may be able to track the trail of beads back to the Zhentarim warehouse.

PROACTIVE FAILSAFES: If the PCs’ investigation is running aground, consider using these proactive elements.

- Zhentarim hear that the PCs are asking questions about Zhentarim agents, safe havens, or both. A number of Zhent thugs (MM, p. 350) equal to half the number of PCs comes to intimidate them into going away. (Adroit PCs can turn the tables, question them, and learn the location of the warehouse.)

- A small squad of Zhentarim agents arrives at the Zhentarim warehouse. The kenku lying in ambush attack them, and the fight spills out into the street right in front of the PCs.

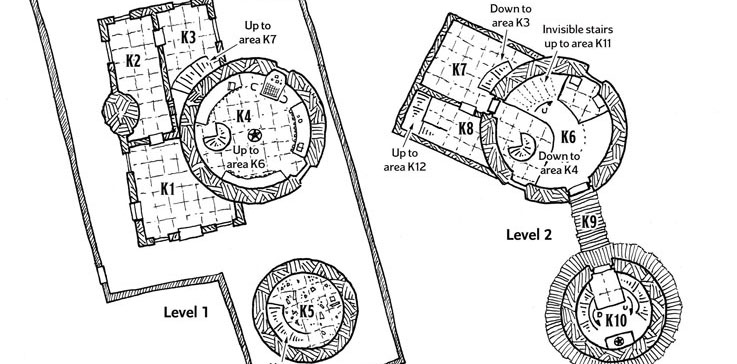

AT THE WAREHOUSE

As initially described in Part 1, after he lost his Eye to Xanathar, Manshoon needed to get back in the game. His agents eventually concluded that Neverember’s son, Renaer, might have another of the Eyes. They were right, although Renaer didn’t know it: His father had given him an elaborate, ivory mourning locket in honor of his mother. The Eye was hidden inside it.

The full dynamic in the first chapter, therefore, is this:

- Zhentarim agents snatch Renaer Neverember and his friend Floon Blagmaar.

- While questioning Renaer in Area Z5, they realize that the Eye is in the mourning locket and take the locket from Renaer.

- Renaer is hauled back down to Area Z2 and tied up next to Floon. Upstairs, the Zhentarim break open the locket (it can still be found in Area Z5), remove the Eye, and give it to a courier to carry to Manshoon.

- Floon is then hauled upstairs for questioning (the Zhentarim want to see if he might be worth a ransom).

- Xanathar’s agents storm the warehouse. They immediately find “the prisoner” (i.e., Floon), assume he’s Renaer, and several of their agents hustle him out to their sewer hideout. Meanwhile, Renaer takes advantage of the confusion downstairs to slip his bonds and hide in Area Z2.

- Xanathar’s agents do a perfunctory sweep of the warehouse and then take off, leaving the kenku behind to kill any Zhents who show up.

DEAD SNAKE: A black flying snake lies dead in the lower yard, pierced by an arrow. (GM Note: The Zhentarim tried to send it as a messenger during the attack, but a Xanatharian watcher shot it down.)

RENAER: Renaer will be able to tell the PCs that he was questioned by the Zhents about the half million dragons his father stole from the city; then they ripped off a locket that was very precious to him. If they find the locket and see the (now empty) secret compartment inside it, Renaer can also tell them that he had no idea that the compartment existed or what was stored inside it.

TO THE XANATHAR GUILD HIDEOUT

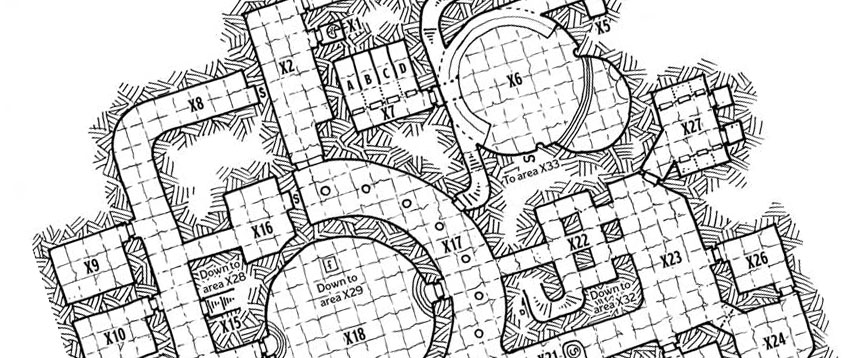

Once the PCs realize that Floon was taken by members of the Xanathar Guild, they’ll need to track them back to the Xanathar Guild Hideout in the sewers.

TRACKING: The Xanatharians exited the warehouse through the yard on the lower level and accessed the sewer half a block away down the alley. A DC 11 Wisdom (Survival) check easily tracks them that far.

Once in the sewers, it requires three successful DC 13 Wisdom (Survival) checks. On a failure, the PCs waste considerable time needing to backtrack and pick up the trail. If the PCs fail the test three times, they’ve wasted too much time: When they arrive at the hideout, they find it abandoned except for the goblin watchers in Q2 and Zemk, the usual keeper of the hideout, in Q5. Floon’s dead body lies in Q7. (Zemk will toss it into the sewer later in the day when he gets around to it.)

However, each time the PCs roll a tracking check, whether it’s successful or not, they can also make a DC 13 Wisdom (Perception) test to notice the guildsign (see below).

(Note: Even if the PCs only manage to recover Floon’s dead body, Volo, albeit a little disappointed with them, will still reward them for completing their mission.)

QUESTIONING THE KENKU: As described on page 25 of Dragon Heist, questioning the kenku may reveal the existence of the guildsign in the sewers (see below). Beyond that, the kenku are largely incapable of describing where the hideout is located. However, they can lead the PCs there (although they’ll be looking for opportunities to lead them into traps or otherwise betray them).

GUILDSIGN: Symbols scrawled in yellow chalk – a stylized representation of Xanathar – is marked at each tunnel intersection in the sewers, indicating the path which should be followed by the direction the main eye is looking. Once the PCs are aware of the guildsign, they can simply follow it back to the hideout.

Neverwinter is destroyed when a small adventuring party (including Jarlaxle Baenre) awoke the primordial Maegera beneath Mount Hotenow.

Neverwinter is destroyed when a small adventuring party (including Jarlaxle Baenre) awoke the primordial Maegera beneath Mount Hotenow.

or you can be brought in as part of the audience for the gladiatorial games (also via X4, but almost certainly arriving in X6 before you’ll have a chance to slip away).

or you can be brought in as part of the audience for the gladiatorial games (also via X4, but almost certainly arriving in X6 before you’ll have a chance to slip away).