Go to Part 1

“If once we shake off pursuit, I shall make for Weathertop. It is a hill, just to the north of the Road, about half way from here to Rivendell. Gandalf will make for that point, if he follows us. After Weathertop our journey will become more difficult, and we shall have to choose between various dangers.” – Aragorn, Lord of the Rings (J.R.R. Tolkien)

UNPATHED ROUTES: The basic route system described above assumes that the route follows a clear and unmistakable path — a road or river, for example. Some routes don’t follow paths, however. These generally take the form of a landmark chain: Head north to Archet, then turn east to Weathertop. Turn south from Weathertop, cross the road, and then head west until you hit the road again.

To handle unpathed routes, you’ll need to add mechanics for both (a) getting lost and (b) getting back on track after you’ve become lost. (This may also include a mechanic to determine whether or not you realize that you’re lost.)

A single route can also include both pathed and unpathed sections.

HIDDEN ROUTE FEATURES: The gansōm bridge was washed out by the spring floods, releasing howling water spirits into the Nazharrow River. Before arriving in the Bloodfens, the PCs were unaware of the presence of goblin rovers. They’re pleasantly surprised to discover that the Imperial checkpoint at the Karnic crossroads has been abandoned, its regiment summoned north to deal with peasant rebellions.

Although I mentioned before that PCs need to be aware of distinctions between the available routes in order to make a meaningful choice between them, that doesn’t necessarily mean that they need to know everything. Some aspects of a route’s speed, difficulty, stealth, expense, landmarks, or hazards can be initially hidden from the PCs and only discovered later.

In some cases, hidden route features can be uncovered before the journey begins if the PCs research the route or can get their hands on better maps.

FORKED ROUTES: Sometimes the choice of route (or additional choices of route) can appear after the journey has begun. These can include detours, in which the fork in the route eventually collapses back into the original route.

Detours are often made in response to hidden route features discovered along the way (the gansōm bridge has been washed out, so you need to figure out a different way across the river). PCs can be both pushed and pulled by detours, however: In addition to trying to avoid bad things on the original route, they might also choose to turn aside to gain some benefit (from an advantageous landmark, for example), usually at the cost of time.

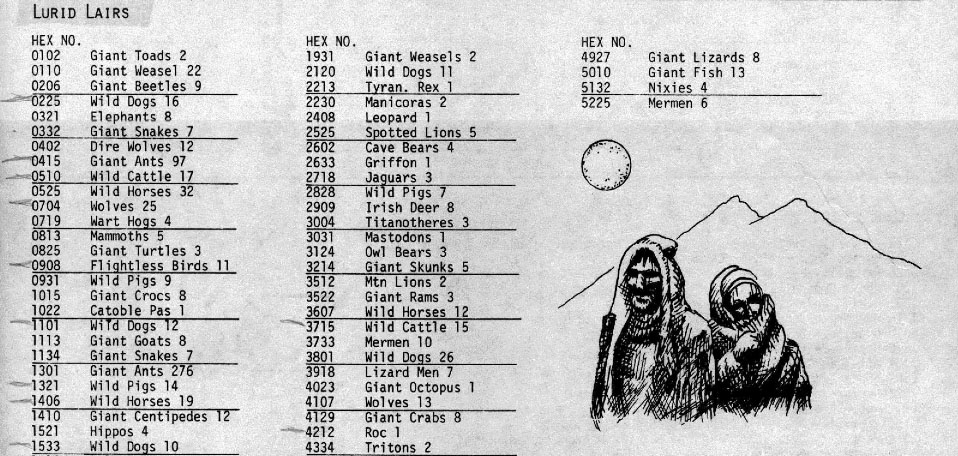

PROCEDURAL CONTENT GENERATORS: Procedural content generators are generally nonessential to a scenario structure, but properly designed they can be large boons in content creation and can even unlock unique gameplay. Other than a random encounter table, what other content generators could we potentially develop?

I think one thing we can immediately rule out is trying to develop a map generator. Nothing wrong with a good random map generator, but it doesn’t feel like it’s directly connected to route travel. The assumption of the route system is that you know where Point A is, where Point B is, and what the general routes between them are going to be.

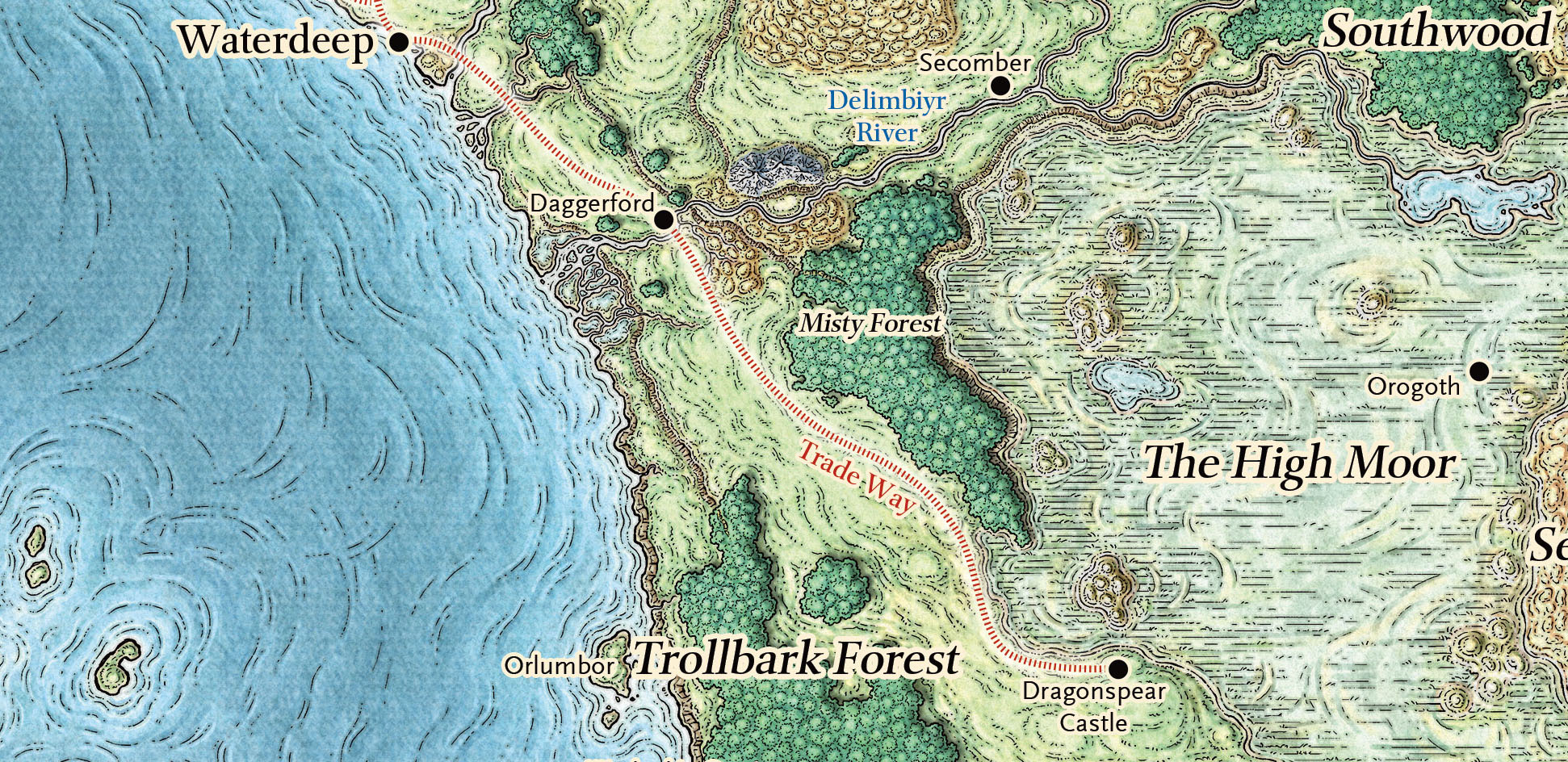

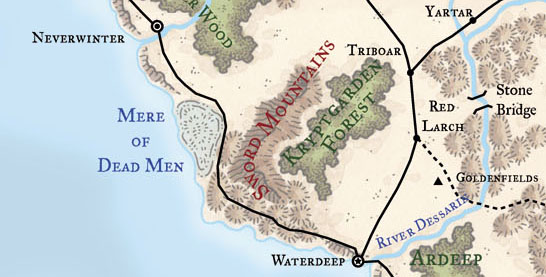

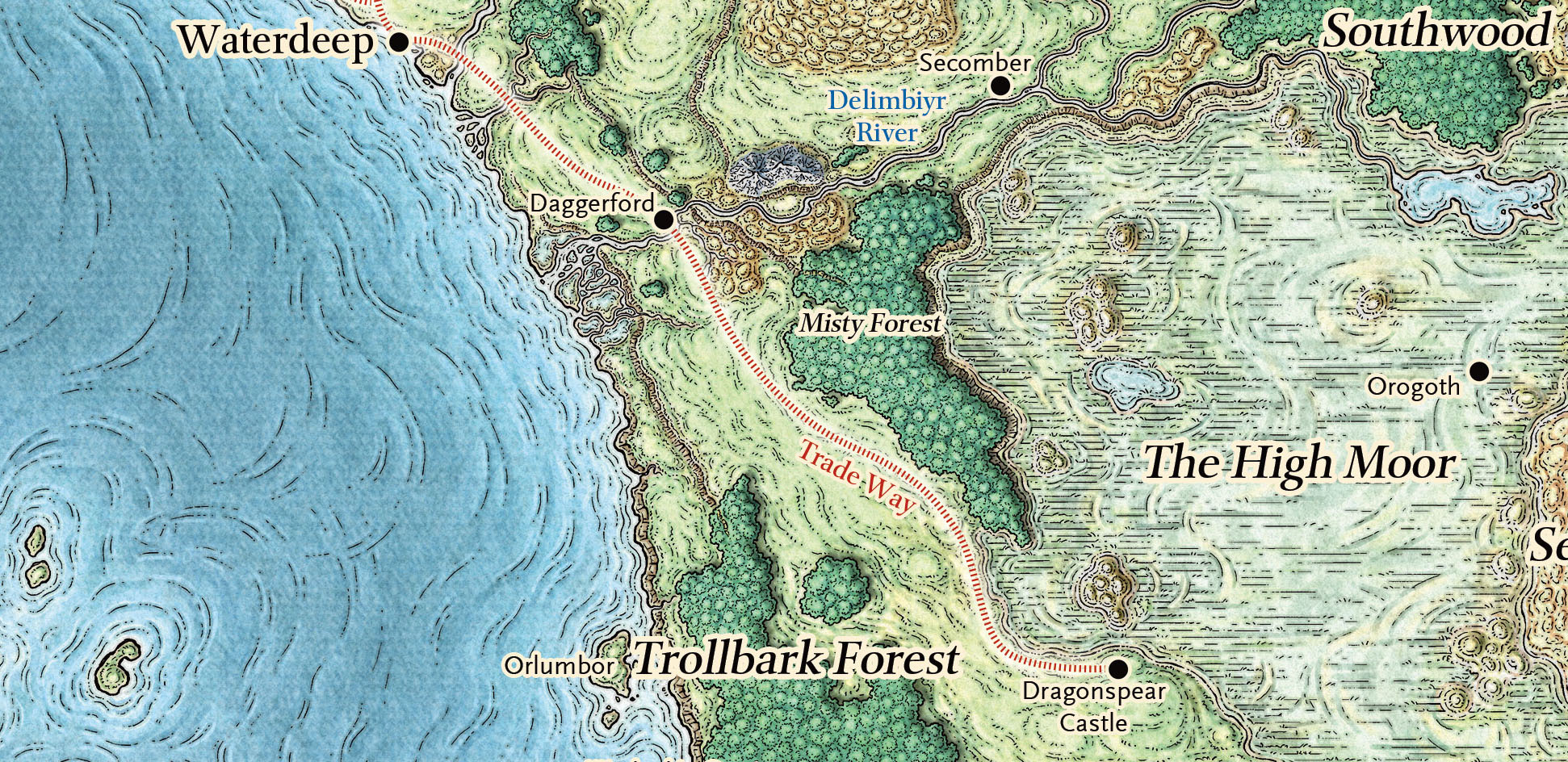

However, you might occasionally faced with a map like this one:

And need to ask yourself, “How can you get from Secomber to Dragonspear Castle?” There’s one obvious route that goes down the Delimbyr River to Daggerford and then along the Trade Way, but is that the only route?

So our first procedural content generator might randomly determine a type of route:

- Road

- River

- Landmark Chain

- Magical

You could bias that so that 1-5 is Road, 6-7 is River, 8-9 is Landmark Chain, and 10 is Magical on a d10 roll. If I literally roll a d10 while sitting at my desk here, I get a 1 and discover that there must be an old, disused road that crosses the High Moor. (It might be a remnant of the Netherese Empire.)

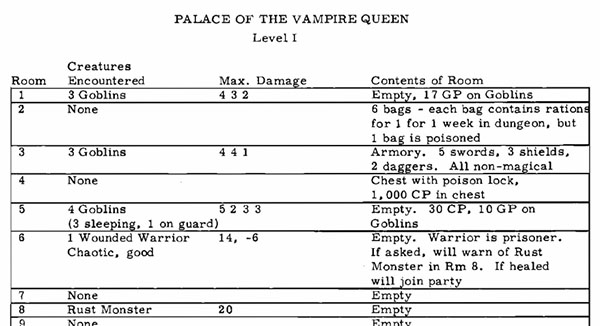

Let’s go back to the Secomber-Daggerford-Dragonspear Castle route on the map above. Remembering that a route is largely defined by the sequence of landmarks spaced along its length, we can see at the moment that the only landmark we know about is the city-state of Daggerford. So perhaps we develop a landmark generator. You could randomly determine a number of landmarks (perhaps 1d6+1) for a given route, and then generate specific landmarks in various categories:

- Settlement (town, village, fortress, shrine, inn)

- Ruin

- Lair

- Route Feature (bridge, wall, tunnel, toll, fork in the path)

- Natural Landmark

There’s likely other categories to be explored, and you can also easily dive down into any number of detailed sub-tables for each of these categories.

Now that you have a list of landmarks for the route, you might want to think about how those landmarks relate to the route itself. A landmark doesn’t necessarily need to be directly on the road, for example, so we could randomly determine the landmark connection:

- On Route

- Detectable From Route (sight, smell, sound)

- Detour (you have to leave the route in order to visit/see the landmark)

As you’re generating landmarks, you may want to get a better sense of how they connect to the wider world. So you might use a path generator to determine if the landmark is functionally a crossroads for many different routes or if it can only be reached along the road, river, or other route that the PCs are currently following.

You can use any number of methods to determine the presence/number of routes connected to the landmark, then randomly determine the type of route (see above), and then use a d8 for compass direction or d6 for hex direction to randomly determine the rough direction of the route.

Where do these other routes go? Unless the PCs express interest, you don’t necessarily need to explore that, although it can often provide good local color. (“About midday you come to the Inn of the Prancing Fairy. It lies at a crossroads with the road leading to Elegor in the north.”) Often you can just look at your map and get a pretty good idea of where they might go.

For example, if the PCs are travelling down the Delimbyr from Secomber to Daggerford and they come to a ruined tower that you determine is a crossroads with a route heading to the southeast, you could pretty easily conclude that there must be a small tributary river flowing out of the Misty Forest that joins the Delimbyr here.

As you’re describing the PCs’ journey, it may also be useful to describe the changing terrain they’re passing through. A terrain feature generator could use a simple mechanic like having a 1 in 6 chance each day of the terrain changing, and then tables to determine the new terrain features that they encounter (likely based on the base terrain type they’re traveling through). Terrain features could include vegetation, debris, obstacles, things seen on the horizon, etc.

RUNNING WITH ROUTES

As you begin running games with the route system, here are a few things to keep in mind.

First, the structure does not inherently make travel interesting. If you think of the structure as a way by which specific scenes (the landmarks and random encounters) can be easily framed, then it follows that you still need to make those scenes meaningful.

By default, the route system will lead you towards a generic travelogue (“…and then we went to X and then we went to Y and then we went to…”). But the best travelogues find ways to elevate the sequence of events. You want your game to resonate with the powerful journeys of The Lord of the Rings, rather than plodding along in the dull procedural of something like The Ringworld Engineers.

If you’re of a dramatist bent, think of what kind of story you want to be telling with this journey: Exploration, a race, escape, survival, self-discovery, edification. Or is the journey simply a convenient framing device for a number of individually interesting and complete short stories? Journeys can set mood (think of the emotional toll of Frodo and Sam’s long trek across Mordor), emphasize a theme (sure are a lot of goblins in these fens), establish current events (passing caravans of refugees from the war), or provide hooks to side quests.

Regardless, think about the agenda of the scenes you’re framing to. Why are you framing to these moments? What’s the bang that forces the PCs to make one or more meaningful choices in that scene? (These topics are discussed at more length in The Art of Pacing.)

If you can’t think of any agenda or bang for a particular landmark, then consider demoting that landmark to a part of the abstract description of the journey or even drop it entirely. (The truth is that the PCs will see a lot of stuff on the road. You’re going to skip over most of it. The important thing is to figure out what stuff you need to focus on in order for the journey to be meaningful.)

THE PROBLEM WITH MULTIPLE ROUTES: A fundamental problem with the route system is the choice between routes. This inherently creates a choose-your-own-adventure structure in which you’re prepping a lot of material for two different routes and then immediately throwing out at least half of that prep as soon as the PCs choose one route over another.

There are, however, a few ways that you can mitigate this problem.

First, you can often minimize wasted prep by having the players choose their route at the end of a session. You still need to broadly prep each route so that a meaningful choice can be made between routes, but this is fairly minimal and you only need to prep the chosen route in fully playable detail.

Second, in many cases there may not actually be a choice between multiple routes. We talked about this briefly before, but if the decision of route boils down to a calculation rather than true choice, then you only need to prep the route that’s calculated to be best.

Third, you can focus your prep on proactive elements that are relevant regardless of which route is chosen.

Being chased by the bad guys is an easy example of this: With the Ringwraiths chasing them from the Shire to Rivendell, the hobbits — and, later, Strider — make a number of route choices balancing speed, safety, and stealth. The threat of the Ringwraiths (and their other agents) make these choices interesting, but you only need to prep the Ringwraiths once.

You can also feature content that the PCs carry along the road with them. For example, you might prep a murder mystery and/or romantic drama that features the team of hirelings the PCs have brought along on the journey. For the “Battle of the Bands” scenario in the Welcome to the Island anthology for Over the Edge, Jeremy Tuohy and I developed an interlinked system of road talk and encounters on the road that create an evolving drama with the NPCs the characters collect along the way.

Fourth, you can find ways to reuse, reincorporate, and recycle material so that even if the PCs don’t see the stuff on Route B on this particular journey, you’ll still end up using it at some point in the future.

BACK TO HEXCRAWLS

Which actually brings us all the way back to hexcrawls.

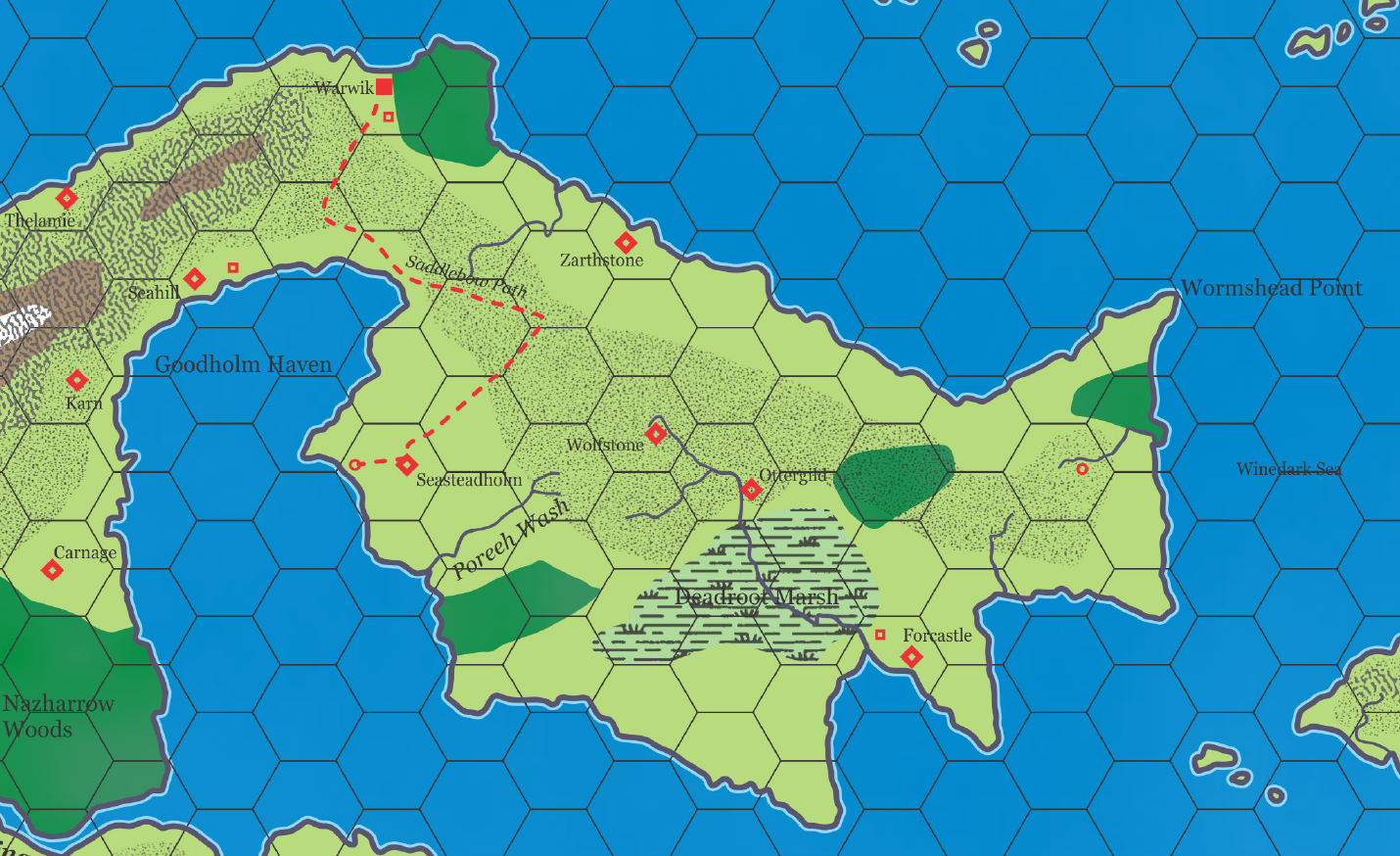

Because it turns out that a lot of the stuff we’ve built into our route system — landmarks, navigation DCs, terrain, travel times, etc. — actually just fall out of a fully stocked hexcrawl with no additional prep whatsoever.

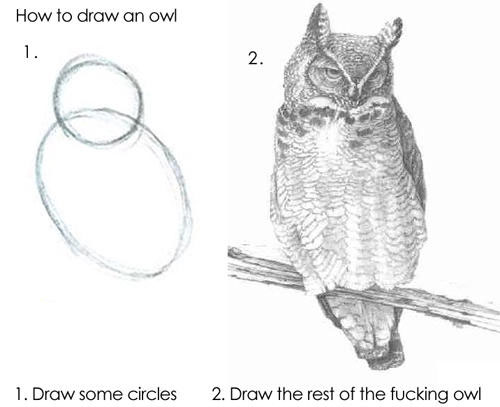

This is one of the many reasons that a truly ready-to-play hexcrawl would actually be one of the highest value supplements a game company could publish. The utility of the hexcrawl is incredibly high to any individual GM, particularly if you can eliminate the inefficient nature of most hexcrawl prep by spreading that value across an audience of hundreds or thousands.

(Unfortunately, most hexcrawl products aren’t fully stocked and ready-to-play. They just provide a very high level overview of the would-be content of the hexcrawl, leaving a lot of the actual work in the GM’s lap.)

To be clear here, I’m not saying that we should abandon the route system and go back to hexcrawling. The hexcrawl system is still optimized for exploration, not travel. What I’m saying is that if you map a route across a fully stocked hexcrawl, then 99% of the work in defining that route for us in the route system can just be directly yanked out of the hexcrawl content.

If you’re working from a hexcrawl, you can also begin experimenting with trailblazing structures in which the PCs create their own routes through the wilderness. In fact, whether you have a system for trailblazing or not in a hexcrawl campaign, you’ll probably find that the PCs just naturally create routes for themselves: They want to get back to the Citadel of Lost Wonders so that they can continue looting it, and they will figure out how to make that happen. These routes almost always take the form of landmark trails, and will often feature the PCs making their own navigational landmarks to fill in the gaps.

THE ROUTE MAP

Whether you’re working from a hexcrawl or not, if your campaign regularly features travel then you will, over time, begin to accumulate a collection of planned routes that crisscross the local region. Over time, it is likely that this route map will evolve into a pointcrawl: As the routes intersect and overlap with each other, the map will develop enough depth that the players can make complex navigational decisions and begin charting out their own routes in detail.

If this is a style of play that appeals to you, it may be tempting to imagine sitting down and planning this elaborate route map ahead of time as part of your campaign prep. There may be a few major, obvious routes where this makes sense, but for the most part I recommend resisting the temptation. Partly because the thought of all that wasted prep makes the little winged GM on my shoulder wince, but mostly because it’s intrinsically more effective to let the players (by way of their PCs) tell you where they want to go and what the important routes are.

In transportation planning there’s a concept called the desire path: These are the paths created by the erosion of human travel across grass or other ground covering. It’s the way that people want to travel, even if the planned or intended paths are telling them to take a different route.

It has become quite common for urban planners to open parks, college campuses, and similar spaces without sidewalks, wait to see where the desire paths naturally form, and only then install the pavement.

You’re doing the same thing here: Following the players’ paths of desire and developing the campaign along the lines that they have chosen.

FURTHER READING

If you’re interested in delving deeper into this sort of thing, I recommend checking out: