GM: So now, at last, Minas Tirith is besieged, enclosed in a ring of foes. The Rammas has been broken, and all Pelennor abandoned to the Enemy. All night the watchmen on the walls hear rumors of the enemy that roam outside, burning field and tree, and hewing any man they find abroad, living or dead. The numbers that have already passed over the River cannot be guessed in the darkness, but when morning, or its dim shadow, stole over the plain, you can see that the plain is dark with their marching companies, and as far as your eyes can strain in the mirk there sprout, like a foul fungus-growth, all about the beleaguered city great camps of tents, black or somber red.

Gandalf: Hmm… can I use my Fireworks skill to whip up a nuclear bomb?

GM: Sure.

Always Say Yes is a bit of GMing advice that gets circulated quite a bit. The example above takes it to a silly extreme, but it illustrates the central problem: There clearly is a point where the GM needs to say no, but the simplistic “Always Say Yes” not only doesn’t help them figure out what that is, it’s more likely to mislead them. Its sole saving grace is that Always Say Yes is at least preferable, in my opinion, to Always Say No, which is where railroading will often take GMs.

Always Say Yes comes from theatrical improv games. And the reason it’s bad advice for an RPG is that improv and RPGs have fundamentally different narrative structures.

In improv, the performers are collaborating to create a world. You always accept new facts about the world because negation doesn’t take you anywhere creatively:

Actor 1: Here we are at Disney World!

Actor 2: No, we’re at the White House.

But even in improv it can mislead performers, because Always Say Yes only applies to the worldbuilding (i.e., stated facts about the world). It doesn’t mean that your character can’t oppose or say no to another character. If the maxim is misapplied in this way, it becomes impossible for improv scenes to have any conflict, draining them of interest.

Note: This is also why Always Say Yes actually can be useful in certain storytelling games based around narrative control mechanics. Many of those games, although not all, feature collaborative world-building.

In RPGs, on the other hand, the GM creates the world and the players take on the roles of characters who live in that world. The players, therefore, are primarily playing a role, not worldbuilding, while the GM’s primary duty is being an arbiter of the fictional reality those characters inhabit. From a game perspective, this is much more like 20 Questions than it is an improv theater game: There’s a “truth” (e.g., the object selected in 20 Questions) that the GM knows to be true and which is being communicated to the players.

Imagine for a moment playing 20 Questions while always saying Yes: It’s technically possible. In fact, just like Gandalf setting off tactical nukes on the Fields of Pelennor, you’re almost guaranteed to “win” every time. And yet you’ve fundamentally broken the game.

So the improv-style Always Say Yes to Worldbuilding doesn’t work in an RPG.

What if we change the target to something like Always Say Yes to Player Plans? This is probably getting us closer to something useful, but it still doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. For a simple example, consider someone saying, “I cast a spell and teleport back to Dweredell!” Okay… but does your character actually have a spell that does that? RPGs have rules that mechanically define characters and what they can (and, importantly, can’t) do.

In addition to a character mechanically lacking the ability to do something, you’ve also got world state (e.g., there’s a teleport interdiction field there) and NPC actions (e.g., someone counterspells the teleport) that can – and at least some of the time should! – negate player intention.

At this point we can easily glide over into another common maxim: Say yes or roll the dice.

This can probably be more accurately understood as “say yes unless the mechanics say no” (since not all mechanics use diced outcomes), but even that’s still misleading because there can, once again, be non-mechanical reasons why a player’s proposed action won’t work (e.g., they want to go the local mage’s guild, but the GM knows there’s no mage’s guild in this village).

DEFAULT TO YES

All of which is why I prefer to use Default to Yes as my maxim of choice here.

Its meaning expands to, “When the players say they want to do something, you should default to letting them do it unless you have a specific and interesting reason not to.” It fulfills the same crucial function of steering the GM away from contrarianism, but also provides a clear standard they can use to figure out when they should be saying No.

Furthermore, if it turns out that there is, in fact, a reason not to Default to Yes, then you can also use the Spectrum of GM Fiat to find the appropriate response:

- Yes, and…

- Yes, but…

- No, but…

- No

And, if those aren’t right, you can always shift to, “Maybe, let’s roll the dice and find out…”

The underlying principle here is the players will generally propose doing things that they would enjoy and outcomes that they desire. So, generally speaking, letting them do and achieve those things will make for happy players.

So why not go back to Always Say Yes, then?

Largely because there’s other stuff that he players also enjoy. That might be challenge (e.g., knowing that they’ve actually earned their victories), simulation (e.g., they want to know that they’re exploring a “real” place), or drama (e.g., struggle is narratively interesting). To generalize, failure is interesting.

GM DON’T #20.1: PREP IS ALL, PREP IS LAW

If we return to our example of the PCs looking for a mage’s guild in a village where the GM knows no mage’s guild exists, however, there’s another pitfall you can stumble into while trying to enforce the fictional reality of the game world.

Imagine that the PCs have come to a large city, perhaps one with half a million people living in it. A player says, “Okay, I want to find a blacksmith who can repair my sword.” You check your description of the city, but it turns out that you didn’t include any smithies in your notes.

This is just like the mage’s guild, right? Your notes for the village didn’t include a mage’s guild, so there was no mage’s guild. Your notes for the city don’t include a blacksmith, so there are no blacksmiths.

… right?

Probably not.

Obviously a large medieval fantasy city is almost certainly going to have at least one smithy. The key insight here is that even if you have hundreds and hundreds of pages of notes detailing your city, you still won’t have recorded every single person, place, and thing. It would be a mistake to believe that the only things that exist in the game world are the things you’ve explicitly written down. Instead, when confronted with a situation like this, the question you should ask yourself is, “Given everything I know about the game world, would it make sense for this to exist? And, if so, what form would it take?”

And, once again, you want to Default to Yes.

If you know that there are no Ivy League schools in Kentucky, then it’s fine to say No if the players want to go looking for one in Paducah. But if they’re just looking for a university with an archaeology department somewhere in the state where they could ask some questions of an expert, then they should be able to find one somewhere in the state!

Once you’ve grokked that principle, the next thing to understand is that this extends beyond cities and states. It scales to almost every level of the game world.

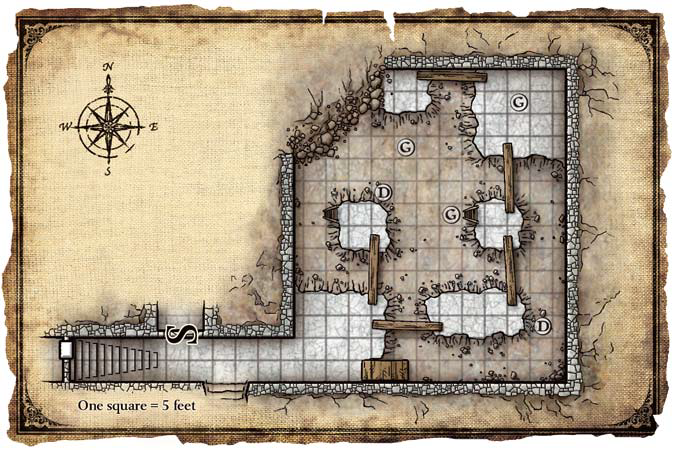

For example, let’s zoom all the way in on a dungeon room. Here’s one from So You Want to Be a Game Master:

AREA 15: CRYPTIC LIBRARY

The room is of crimson and dark wood beneath a vaulted ceiling. A set of tall double doors, matching the ones you entered through, faces you on the opposite side of the room. A large pentagonal mahogany table stands in the center of the chamber. There are five large bookcases stuffed full of tomes and scrolls along the paneled walls. Sunlight streams in through bay windows with a built-in bench. The windows are leaded stained glass depicting a subtle pattern of golden florets.

Consider those bookcases. In our key, we might even include additional details about the books:

BOOKCASES

The books and other documents here are all of an occult nature. There is a focus on Natharran mythology, particularly an enigmatic figure known as Basp-Attu. A DC 15 Intelligence (Arcana) check identifies Basp-Attu as a dual-bodied demon said to have been born from the mixed ichor of two dead gods during the War of Falling Stars.

But even with all of this detail, we still haven’t completely detailed the bookcase.

- What if a PC wants to grab the heaviest book off the shelf and use it to bludgeon the cloaker that’s just ambushed them? How big is the biggest book? Is it big enough to do serious damage?

- “Are there are any books with a green cover? Maybe I can fool the goblins into thinking it’s a copy of the Verdigris Bible.”

- “I want to tip the bookcase over on top of the cloaker!” Have the bookcases been fastened to the wall?

- “What’s the single most useful book about Basp-Attu here?”

- “Are there volumes here that would be useful additions to the collection at the libram at my kolledzh?”

To be clear, the point isn’t that you should be prepping answers for all of these questions. The point is to recognize that you can never prep the entire world. The players will always have a question you don’t know the answer to and you will always be performing acts of creative closure at the table.

Unless, of course, you make the mistake of believing that you have prepped everything and that your prep is absolute and immutable law. If you do that, then you’ll have started walking down one of the many paths to pixelbitching — aka, playing a game of Guess What the GM Prepped.

Feng Shui, the roleplaying game of Hong Kong action films, actually pushes this concept of the uncertain game world and creative closure one step further by specifically giving the players unilateral narrative authority to simply declare that a prop they want is present in any fight scene. Want to fight with a ladder like Jackie Chan in First Strike? Bring a rolled up magazine to a knife fight like Jason Bourne? Throw your jacket over a support cable and zipline to the ground? You don’t need to ask the GM if there’s a ladder at the construction site, a magazine on the coffee table, or a cable attached to the building.

This works because when the GM says, “The elevator doors open to reveal a floor full of cubicles,” everyone at the table is, in fact, picturing a different place. There are some details — like the fact there are computer monitors on the desks — that are shared in all of our imagined spaces, but there are other details that aren’t. As we interact with and explore the space together, though, our visions adapt and converge. This mostly happens without friction and often without us ever really consciously thinking about how our mental image of the cubicle farm is morphing and changing.

While in my experience the GM’s vision of the space probably morphs less than the other players (because they are, in fact, the arbiter of the world), it’s important for them to understand that their imperfect vision will, in fact, also be adapting and becoming more fleshed out: I didn’t know there was a smithy in this town, but now I do. I had not specifically pictured staplers on those desks, but once Aaron snagged one I can clearly see them. I had no idea that The Two-Faced Demon by Attansea Millieu was a rare tome, but apparently there’s a copy sitting on this bookshelf.

Discovery is the great joy of collaboration, and if you can truly open yourself to that collaboration, who knows what exciting adventures those discoveries may take you on?