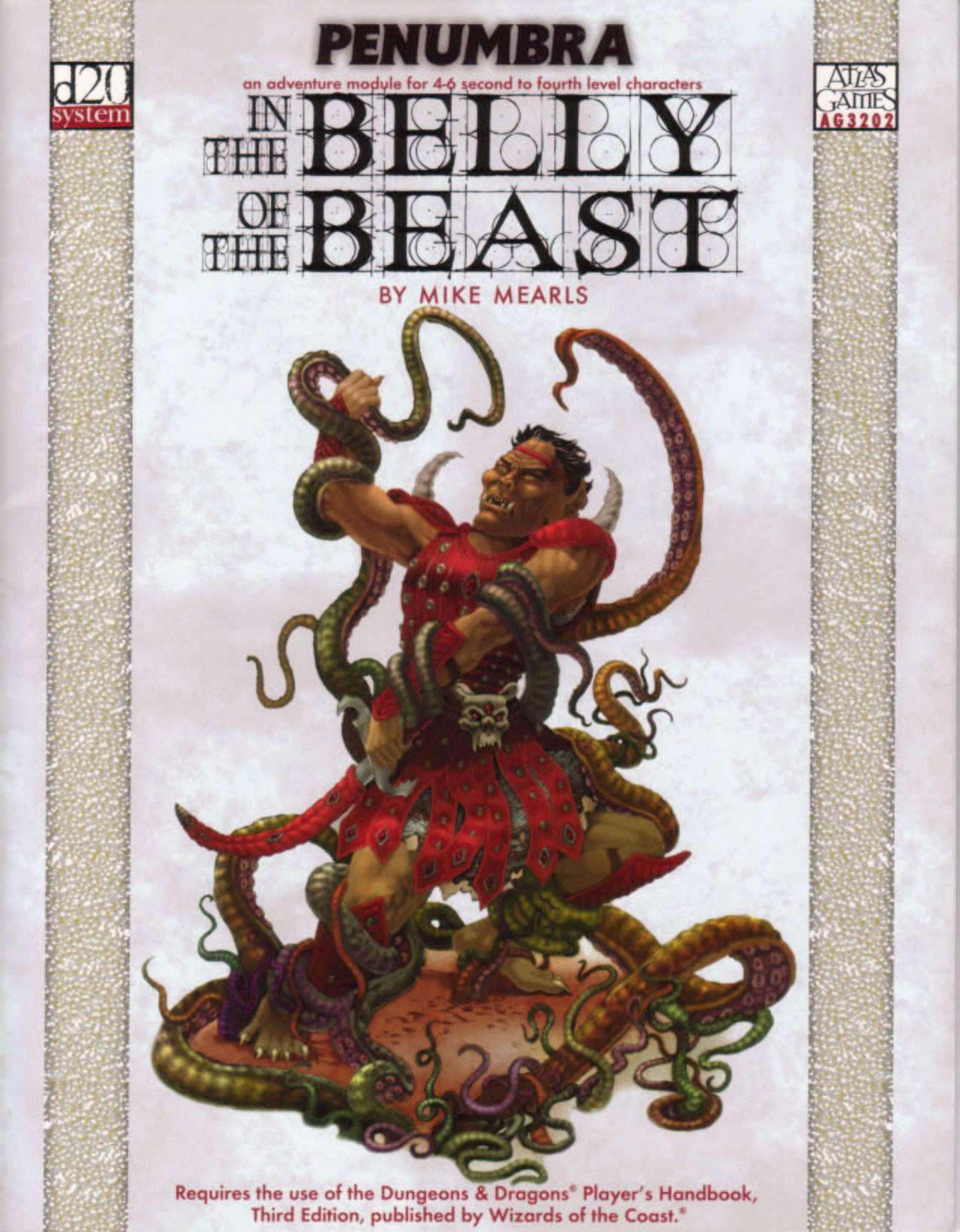

In the Belly of the Beast is not only an excellent product in its own right, it deserves to be the template by which other adventures will be written.

Review Originally Published May 21st, 2001

Not only is every Penumbra product from Atlas Games a tour de force of excellence, each betrays an immense talent which is capable of constantly providing a fresh perspective to every aspect of a high quality product. In the Belly of the Beast, sprung forth from the brow of Mike Mearls, offers no contradiction to this rapidly emerging reputation.

PLOT & CONCEPT

Warning: This review will contain spoilers for In the Belly of the Beast. Players who may find themselves playing in this adventure should not read beyond this point.

In the Belly of the Beast begins when the players are approached by Bruno Mezzia, son of Hallan Mezzia and heir of House Mezzia – a powerful and wealthy family in possession of a trading empire. He wants the PCs to help him take care of the Ring of Iron, a local guild of thieves and slavers which has been causing problems. What the PCs don’t know, though, is that Bruno is trying to establish his own position of power within the city’s underworld – and is planning to use the PCs to do it.

When the PCs and Bruno attempt to go after a stronghold of the Ring of Iron located in the city’s sewer system, however, things go wrong: Unknown to Bruno (or the PCs), a member of the Ring of Iron has come into possession of a rare and strange magical item belonging to a necromancer. In fact, the necromancer from whom they had stolen it had – in turn – stolen it from a tribe of orcs.

What none of them knew is that the magic item in question was a chrysalis – an egg from which the demon Vog Mor would be born into the world. While located in the sewer stronghold, the egg has hatched – trapping the Ring of Iron, the necromancer’s apprentice (who killed his master and now pretends to be the master), and a war party of orcs who came after the egg inside the belly of the slowly emerging Vog Mor.

Bruno and the PCs, of course, end up in exactly the same place.

So, to sum up:

The PCs, the head of a would-be crime family, a gang of slavers, a war party of orcs, and a would-be necromancer (who is slowly going insane) are all trapped in the belly of a demon who, in a few short hours, is going to wake up and take over the world.

Cool.

SOMETHING NEW IN MODULES

“This adventure is roleplaying-intensive.”

How many times have you seen a module claim that? 15? 50? 500 times? How many times have you read those modules and then found out the author was telling you a bald-faced lie?

Every single time, right?

The problem with writing a “roleplaying-intensive” module is that, by its very nature, character interactions cannot be as neatly summed up as “when you open the door you see 5 orcs in a 10’ x 10’ room playing poker”. Monsters meant for slaying, traps meant for escaping, dungeons meant to explore. These can be quantified, described, and mapped with precision. Negotiations with King Strophius to release the Mycenaen prince he holds for ransom? That’s a bit more difficult to put down on paper – and ultimately relies upon the particular DM and PCs who are handling the negotiations.

So “roleplaying-intensive” adventures are an interesting conundrum: You can make ‘em. You can run ‘em. You just can’t buy ‘em.

Or so I thought.

There are times when I love being proved wrong.

In the Belly of the Beast is a roleplaying-intensive adventure, and it really, really, really works. No, really: It does. Would I lie to you?

So how does Mearls do it?

First, he gives you five different factions of power in the demon’s belly: The PCs (which he, of course, leaves undefined), Bruno Mezzia and his thugs, the Ring of Iron slavers, the Blood Hatchet orc war party, and the “necromancer” and his servant. Each group is detailed, and each member of the group is detailed – giving the DM a full grasp on his cast of characters.

Next, he gives everyone a common goal: Escape the demon belly.

Then, he gives everyone a common enemy: The servants of the demon who are trying to get past the impromptu barricade and kill everyone.

And then, to round out the foundation of the scenario, he gives everyone a reason for distrusting everyone else – and a reason to ally with one another against the others.

Into this potently developed dynamic, Mearls then adds an exhaustively detailed series of events (and potential events) which allow the mutable plot of the adventure to form. Mearls carefully designs this episodic plot so that it can adapt to whatever actions the PCs may take, giving the DM a strong helping hand without forcing them to tie their players into strait jackets. At the same time, he doesn’t allow the episodic nature of his narrative structure to dominate the actual playing experience – tying his events to each other in a variety of ways, so that the underlying dynamic of the scenario will create a holistic and memorable gaming experience no matter who plays it… or how.

CONCLUSION

So, at the end of the day, In the Belly of the Beast lays claim to being something a little different, something a little new, and something which should definitely find its way into your gaming library. In fact, if your players aren’t able to look back fondly and say, “Hey, remember that time we were stuck in the belly of Vog Mor?” then you’ve definitely made a big mistake in not grabbing this module up and running it.

Now, a real quick note on a weakness I think the product has: It is marketed as containing a “tear-out section”. This section contains the stat sheets for the major NPCs, a combat chart, a hand-out, and the adventure’s map. I, honestly, cannot imagine anyone actually bothering to tear this section out of the module – and the net result is that information which could have been presented in a truly useful manner, now disrupts the lay-out of an otherwise excellently presented adventure. While I applaud Penumbra for experimentation on the one hand, on the other I wish that they would focus on producing the high quality product they’ve proven they’re ably capable of producing and leave the gimmicks for when they are truly deserved and needed.

That’s my assessment as a reviewer, GM, and player. Now, if you’ll indulge me for a moment, I’d like to pass my judgment on this product as a freelancer who has written or contributed to roughly half a dozen D20 products:

In the Belly of the Beast establishes a paradigm for developing roleplaying-intensive modules. Mearls is, of course, building upon design tools which have been developed before, but, to my eyes, he has done so by creating the ground floor of something that deserves a very close look. I, personally, am already working on a module which will play around with and develop these concepts – and, once I’m done with that, I’m probably going to take a look at combining it with an old idea of my own and seeing how they can be combined to enhance a dungeon environment. I encourage other freelancers (and GMs) to look at Mearls’ work in this light as well – not only to duplicate what he has done, but also to open your minds to doing things using new tools and methods.

Okay, I’m off my soapbox. You can stop reading and go out to buy your own copy now.

…

No, seriously. I’m done.

…

C’mon. Get out of here.

…

Look, I’m going to call the cops if you don’t leave!

…

Okay, that’s it. You’re in trouble now, big guy! You just wait and see!

Style: 4

Substance: 5

Author: Mike Mearls

Publisher: Atlas Games

Line: Penumbra

Price: $8.95

ISBN: 1-887801-96-0

Product Code: AG3202

Pages: 32

This adventure had a HUGE impact on me as a GM. I’ve previously discussed its influence on the Universal NPC Roleplaying Template, and you can trace its impact all the way into So You Want to Be a Game Master. I think it would be fair to say it’s directly or indirectly impacted almost every single roleplaying scene I’ve run in the past quarter century.

I also remember it being incredibly effective in actual play. The faction setup, the flexible diplomatic relations, the event sequence, and the looming threat of Vog Mor all combined beautifully. (Although, if I recall correctly, I souped things up with some material from The Book of Fiends.)

So, yeah, this one is a certifiable classic. Really deserves to be on more Best Adventures of All-Time lists.

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.