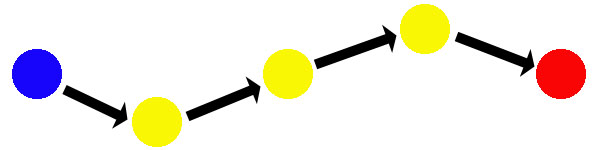

Most published adventures are designed around a structure that looks like this:

You start at the beginning (Blue), proceed through a series of linear scenes (Yellow), and eventually reach the end (Red).

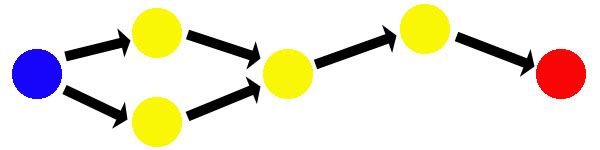

Occasionally you may see someone get fancy and throw a pseudo-option into things:

But you’re still looking at an essentially linear path. Although the exact form of this linear path may vary depending on the adventure in question, ultimately this form of design is the plotted approach: A happens, then B happens, and then C happens.

The primary advantage of the plotted approach is its simplicity. It’s both easy to understand and easy to control. On the one hand, when you’re preparing the adventure it’s like putting together a scheduled to-do list or laying out the plot for a short story. While you’re running the adventure, on the other hand, you always know exactly where you are and exactly where you’re supposed to be going.

But the plotted approach has two major flaws:

First, it lacks flexibility. Every arrow on the plotted flow-chart is a chokepoint: If the players don’t follow that arrow (because they don’t want to or because they don’t realize they’re supposed to), then the adventure is going to grind to a painful halt.

The risk of this painful train wreck (or the necessity of railroading your players) can be mitigated by means of the Three Clue Rule. But when the Three Clue Rule is applied in a plotted structure, you run the risk of over-kill: Every yellow dot will contain three clues all pointing towards the next dot. If the players miss or misinterpret a couple of the clues, that’s fine. But if they find all of the clues in a smaller scene, they may feel as if you’re trying to spoon-feed them. (Which, ironically, may cause them to rebel against your best laid plans.)

Second, because it lacks flexibility, the plotted approach is inimical to meaningful player choice. In order for the plotted adventure to work, the PCs must follow the arrows. Choices which don’t follow the arrows will break the game.

This is why I say Don’t Prep Plots, Prep Situations.

NODE-BASED SCENARIO DESIGN

Part 2: Choose Your Own Adventure

Part 3: Inverting the Three Clue Rule

Part 4: Sample Scenario

Part 5: Plot vs. Node

Part 6: Alternative Node Design

Part 7: More Alternative Node Designs

Part 8: Freeform Design in the Cloud

Part 9: Types of Nodes

ADVANCED NODE-BASED DESIGN

Part 1: Moving Between Nodes

Part 2: Node Navigation

Part 3: Organization

Part 4: The Second Track

Part 5: The Two Prongs of Mystery Design

Part 6: Node-Based Dungeons

THE SECRET LIFE OF NODES

Part 1: Secret Life of Nodes

Part 2: Node-Based Campaigns

Part 3: Fractal Nodes

Part 4: Nodes Aren’t Everything

Part 5: Naturalistic Node Design

You say spoonfeed, but I say railroad. As a player, nothing is more frustrating than my character’s decisions being meaningless. While I appreciate the necessity of having a story to have an enjoyable game, I do not appreciate attempts to dictate what my character does. I enjoyed reading this immensely.

Hi,

You probably already saw that, but I thought you might be interested. MWP have a brand new Leverage supplement : Node-Based Capers. http://rpg.drivethrustuff.com/product/111583/Leverage-Companion-08%3A-Node-Based-Capers

[…] well to setting the tone and mood of a scene or encounter. There is usually an intricate plot (or node) structure that interweaves various overlapping storylines. Combat is deadly, and for that reason […]

[…] of the concepts presented here are partly based on Justin Alexander’s node-based scenario approach to writing Pen & Paper RPG […]

[…] Как и в случае других структур игр-загадок, тут я перехожу к проработке ключевых узлов сюжета, разбивая его на отдельные, легко управляемые и легко продумываемые части. […]

[…] The Alexandrian 27.03.2010 […]

[…] yesterday, when the RPG post I did prompted me to re-read some old posts on blogs I particularly like, which led me circuitously — as internet rambles do — to a new blog (which I’m […]

[…] types to use, and ultimately wrote down six as the “nodes” of the story (laid out in a most excellent post here). As a basic skeleton, I imagined the flow of the story going something like: start at […]

[…] has proven invaluable to my most recent campaign (and likely to my next one). His series on Node-Based Scenario Design, Urban Crawls, The Art of Pacing are top notch. Really anything from his Gamemastery 101 is great […]

[…] Now comes the more in depth methods of adventure prep, which can be short but more importantly are informed by the ideas written in the outline. I would write my own but honestly it’s been covered more thoroughly and better than I could ever do by The Alexandrian […]

[…] adventure is “node based“, which means that players can choose their own path, discovering locales and clues as they […]

[…] website The Alexandrian is chock full of excellent GMing advice, particularly their posts on “Node-Based Scenario Design.” Definitely worth checking […]

[…] be something of a mystery. As such, I can think of no better way to prep this adventure than using nodes, as detailed by The Alexandrian. Nodes are a fantastic tool for organizing important locations, […]

[…] quand il faut s’arrêter et repasser à une scène. Je la trouve aussi très propice aux structures de scénario non-linéaires que j’utilise, parce que ça permet aux joueurs de continuer à intervenir tout en […]

[…] that can appear dependant on the Point of Story the party are working towards. This goes back to node-based scenario design, and particularly the inverted three-clue rule; each PoI will provide clues that point both towards […]

[…] Node Based Scenario Design: Good blog article on the episode’s topic. […]

[…] and summarize the concept, but if you want you can read the whole thing on his site, starting with Node-Based Scenario Design – Part 1: The Plotted Approach. Since we have been talking about the sandbox section of Lost Mine of Phandelver, and since a […]

Hi Justin. I’ve been reading this series and your post about prepping situations instead of plots. How can I distinguish a node and a situation when prepping my game? I understand the concepts and have the feeling that they can really improve my game, but I’m still struggling to work with them combined. In my prep notes, should I think about the story in terms of nodes, and them prep every node with situations, is that it? Or the opposite?

Nodes are a way of thinking about how the PCs can conceptually navigate a scenario. The simplest example is the clue pointing to a location: Knowing X lets them go to Y.

“Prepping a situation” is about rejecting the idea that an RPG scenario is about a predetermined sequence of events (a “story” or “plot”), and instead embracing the idea that an RPG scenario is a collection of tools or toys that the GM actively plays during the session (the same way that the players are actively playing their characters).

The two techniques can overlap: The nodes you prep can OFTEN double as the toys/tools you’re actively playing (proactive nodes are a really clear-cut example of this); or they may usefully group them together (all of Mafia Joe’s goons are in Node 3: Mafia Joe’s Den of Goons, or whatever).

Similarly, although the mentality of “story” can influence the design of a node map, my first step in design a node-based scenario is generally to just look at the SITUATION in the game world: Who knows each other? Who’s working for who? What are people trying to do? Where are they doing it?

[…] surrounding scenario writing and plot preparation. This led me to one of my favourite essays ever: Node-Based Scenario Design, written by Justin Alexander, aka The Alexandrian. I highly recommend reading it before continuing […]

I have been struggling to prepare adventures with locations and details that worked with each other. I was able to run a homebrew murder mystery at a Sun Monk monastery thanks to your help outlining the node system and three clue rule. I had all the tools I needed to move on the characters’ actions and it was really memorable for them.

Thank you. Because of these essays, I can take steps to facilitate games my players look back on fondly.

[…] the first time, I incorporated node-based scenario design into my campaign planning. In terms of tabletop RPGs, the three nodes can be locations, events, or […]

[…] aren’t familiar with it, you can read the original post series on The Alexandrian by clicking this link. To summarize, however, NBSD generates a limited “choose your own adventure” style of […]

[…] ezt a kalandot írtam már ismertem Justin Alexander klasszikus Node-Based Scenario Design című cikkét (eredetileg a magyar fordítást olvastam. Köszi Urban!), de különösen a […]

[…] need to go through the parts and update some of them. I’ve read Alexander’s articles on Node-based Scenarios a few more times, and the followup articles he’s written. I think I have a better […]

[…] aren’t familiar with it, you can read the original post series on The Alexandrian by clicking this link. To summarize, however, NBSD generates a limited “choose your own adventure” style of […]

[…] the first time, I incorporated node-based scenario design into my campaign planning. In terms of tabletop RPGs, the three nodes can be locations, events, or […]

[…] valahol Alexandrian three node structure/csomópont alapú kalandtervezés című cikkéből ered (angol eredeti, a megvilágító erejű példa és a magyar fordítás: első és második). Ezt a cikket a saját […]

[…] when you need node-based scenario design. Created by Justin Alexander on his Alexandrian blog the method focuses on linking together nodes, […]

[…] and running a technical problem like an investigation (using techniques like the Three Clue Rule, Node-Based Design, Relationship Maps, and Progress Clocks) actually makes some sense. If we want to take it as step […]

[…] produce enough plot to lead the players to the next location. Modern adventures ultimately take the Plotted Approach which we used to call a rail road. All aboard the plot train, woo […]

[…] Całkiem solidnym, choć mającym już swoje lata źródłem informacji o pisaniu liniowych przygód jest seria artykułów „Node-Based Scenario Design” na blogu Alexandrian. […]