Here’s a common misunderstanding I often see voiced on messageboards: Choosing which direction you’re going to go in a dungeon isn’t a meaningful choice because the players have no way of distinguishing between the choices.

While this can be true, the reality is that it generally shouldn’t be true. And if you’re consistently finding it to be true, there’s probably something wrong with the way you’re either designing your dungeon or running your dungeon.

TWO TYPES OF CHOICE

Before we begin, I think it’s useful to remember that there are two types of meaningful geographic choice that can happen in a dungeon.

First, there’s the type most people talk about: Selecting which encounter you’re going to face next. (In other words, if you go left you’ll encounter the goblins and if you go right you’ll encounter the vampires.)

In many cases, this sort of choice is, in fact, a random number generator: If you have nothing to distinguish between the choice of going right or the choice of going left, you might as well flip a coin. With that being said, however, there are several ways you can deal with that it’s probably a good idea to explore them in your dungeons:

- Foreshadowing. The path to the left has tracks showing that it’s heavily traversed by small humanoids. The path to the right has been surrounded with crude goblin holy symbols and anyone familiar with goblin runes can read the word “NOSFERATU” spelled out in crude syllables.

- Interrogation. Either friendly or otherwise. For example, you revive the goblin scout you knocked out in this room and you force him to tell you that his tribe lives down the left path and that there are vampires living down the path to the right. But his people also pay tribute to the vampires, leaving them totally impoverished but suggesting that the vampires probably have a huge hoard of treasure. (He might be lying about that last bit.)

- Rumor Tables. Or similar rumor-gathering mechanics. The PCs end up with potentially valuable navigation information about the dungeon before they ever go into it.

- Arnesonian Megadungeon. In the Arnesonian megadungeon, lower levels are always more difficult. Which means that PCs always have a meaningful choice when confronted with the option of going down or continuing to explore their current level.

And so forth. The choice only needs to be blind if the GM and/or the players choose to leave it blind.

SECOND VERSE, COMPLETELY DIFFERENT FROM THE FIRST

With all that being said, it can be difficult to consistently avoid the “random number generator” with that first type of choice. And, in my opinion, that’s OK because that’s not the most interesting type of meaningful geographic choice in a dungeon environment. THAT choice happens when you revisit known terrain.

See, the first pass through a given chunk of dungeon is like the legwork in Shadowrun: You’re gathering information. You may not know how this information is going to be useful yet, but the more you can learn the better off you’ll be when it comes time to run the “heist”.

The heist, in this case, can take a lot of different forms.

For example, it’ll probably start small: “I think if we go this way, we’ll hook back up to these rooms we explored earlier. Or we can go down these stairs and go into completely virgin territory. Whaddya think?”

But it can escalate fast:

“Oh shit! We’ve pissed off the dark elves! Do we make a straight race for the surface? Do we try to lead them into an ambush amidst the grotto of dinosaur bones? Or do we try to hide out in that secret crypt we found?”

“Doubling back you discover a warband of ogres and orcs have moved into the cavern. It sounds like they’re heading for the surface. Do you try to sneak around through those side passages and warn your friends? Or just stay here where you’ll be safe?”

“Okay, we’ve made an alliance with the goblins. They’re saying they can help us secure the eastern stairs so that we’ll have a secure line of retreat when we fight those feral vampires down on level 3, but we’d need to pay them some sort of tribute.”

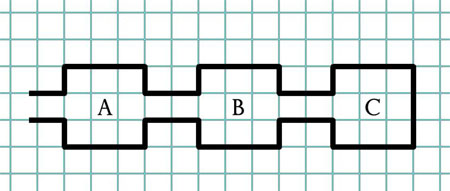

One of the key aspects to this second type of choice is to break away from the idea of “room = encounter”. In fact, it’s most useful to break away from the “encounter” mindset almost entirely. The dungeon has to be a strategic landscape and not just a collection of disconnected tactical challenges.

What can really emphasize this sort of thing is any dungeon complex large enough that the PCs will be visiting it multiple times. (Assuming, of course, that the situation in the dungeon changes and grows organically between visits.)

“Well, it looks like they’ve built barricades in the main hall. Do we send a magical missive to our goblin allies and try to coordinate a simultaneous assault on their flank? Or do we try to slip through the fungal arboretum and just circle around them?”

It’s in this second level of meaningful choice that xandering the dungeon becomes particularly useful. Without the tapestry of interconnections it provides it becomes much more difficult (or impossible) for these kinds of choices to evolve: In a linear dungeon, the bad guys have fortified the main hall and… well, that’s it. You can’t sneak around. And they must have trashed your goblin allies when they came through them. It reduces a rich strategic choice into a boring tactical one.