IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

Session 9A: Gold

Tee must have made some sort of noise, because the woman suddenly whipped around, “Who’s there?”

When, where, and why should you roll to resolve NPC actions?

This is one of those areas where most people seem to assume that the way they do it is the way everyone does it and that there’s really no other conceivable way that you could or should do it, which tends to result in a lot of gnashing of teeth and bloody tears when these preconceptions suddenly collide with a different gaming style/preference/methodology.

One thing that is universally true: You can’t always roll for the NPCs.

“Oh yes you can!”

No, seriously. You can’t.

About 75,000 people live in Ptolus. (And that doesn’t even count the monsters.) At any given time, the absolute maximum number of those people I’m actively tracking is maybe 75. Even if you were a hundred times better than me (and, thus, actively – and absurdly! – actively tracking 7,500 people simultaneously), you’re still only engaged with 1% of the population. At any given moment, therefore, there are vast swaths of the campaign world for which you are assuming activities and outcomes based on various degrees of common sense and creative instinct.

And here’s something that most GMs hold to be true: You roll for the NPCs at least some of the time.

“Whaddya mean most?! You have to at least roll for attacks, right?!”

You don’t, though. Some GMs fudge those outcomes. Others use aggressively player-faced mechanics in systems where the actions of NPCs are only mechanically resolved if they’re directly engaged with and opposed by a PC.

The vast majority of GMs are going to be somewhere between these two radically opposed poles, however. At the beginning of this session’s campaign log, you can get a decent glimpse at how I generally handle things (with some variation depending on both circumstance and the system I’m using).

First, using dramatist principles, I decided that having Linech’s mistress (Biesta) searching Linech’s office for shivvel during the PCs’ attempted infiltration would make for a good scene.

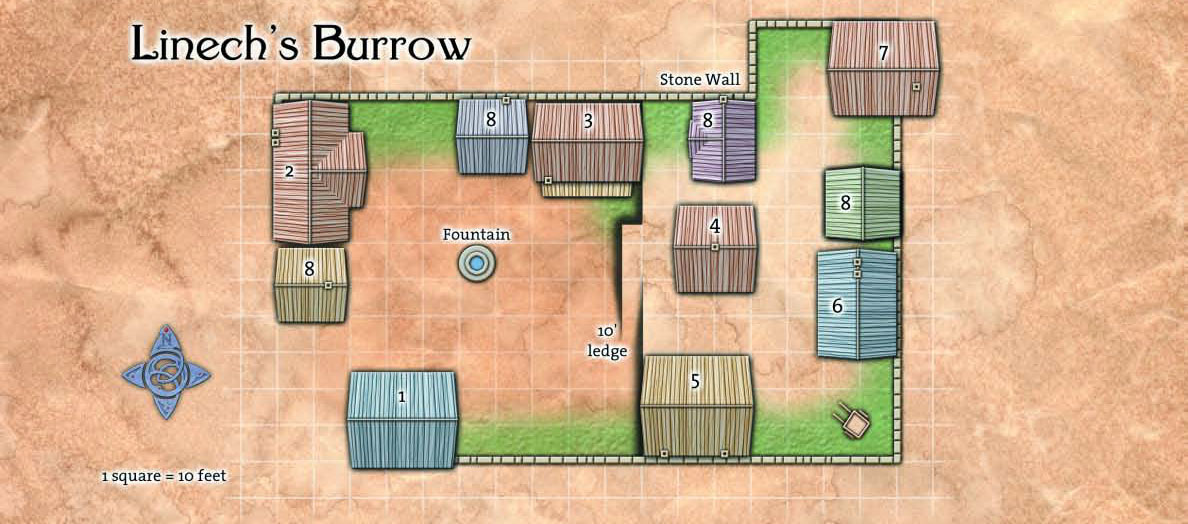

Second, using simulationist principles I set up an initial condition that looked like this:

- Guards (2) – in area 4

- Guards (2) – in area 8

- Guards (4) – at gate

- Linech – in area 7

- Oukina – in area 7

- Ruror – outside area 7

- Biesta – approaching Linech’s office, she arrives in 3d6+5 rounds (looking for shivvel; shivvel in area 3 is gone; she isn’t wearing her armor)

(This is a pretty basic example of an adversary roster.)

SETTING UP INITIAL CONDITIONS

In creating these initial conditions, the first thing you’ll note is that I haven’t tried to simulate the entire nightly schedule for Linech’s burrow. For example, I haven’t said, “Biesta will sneak into his office and steal shivvel between 12:00 and 12:15 AM.”

Why not? Primarily because, at least in this particular scenario, that’s a lot of wasted prep. The PCs are unlikely to see more than one specific slice of the burrow’s schedule. Secondarily, because missing the dramatic interest of Biesta’s presence in the office because the PCs didn’t happen to show up in a specific 15 minute window isn’t a desirable outcome for me (and is also wasted prep).

Those who prize simulationism above all other concerns may balk at this. But I refer you back to our previously established truism: You can’t always roll for the NPCs. And, in a similar vein, you can’t perfectly simulate the daily schedule of all 75,000 inhabitants of Ptolus. At some point you are making an arbitrary decision about the initial conditions of any locale that the PCs begin interacting with.

Because you can’t simulate all 75,000 inhabitants of Ptolus, there is always some degree of compromise, and that means that prepping eighteen different sets of initial conditions doesn’t make any sense: No matter how many you prep, the PCs will never encounter more than one set of initial conditions (by definition).

(There are exceptions to this: If a scenario is likely to feature the PCs putting a location under surveillance, then you will, of course, want to set up the typical daily schedule for that location. Maybe mix in a few random events to vary it from day to day without needing to hand prep every day if it’s likely to be a lengthy surveillance.)

AFTER FIRST CONTACT

With all that being said, the second thing to note here is that I’ve inherently built uncertainty into the initial conditions.

One thing to remember is that I actually have no idea how the PCs are going to approach this scenario: They might sneak in. They might fight their way in. They might come up with some completely different solution I couldn’t even imagine.

These initial circumstances are designed to create interesting complications for the PCs, which they’ll either need to avoid or interact with in order to accomplish their goal. How will they avoid them? How will they interact with them? I don’t know, so I’m not going to waste a lot of time thinking about it. Following the precepts of Don’t Prep Plots, these are all tools in my toolbox; and I’ll improvise with them during actual game play.

Which is what you see play out at the beginning of the campaign journal:

- As the PCs arrived onsite, I rolled 3d6+5 to see how many rounds it would be until Biesta arrived.

- Because Tee waited behind the chimney “for at least a minute” to make sure she hadn’t been spotted climbing up, it meant that Biesta arrived in the office before Tee did.

- We roll a Move Silently vs. Listen check to determine whether or not Tee is aware of Biesta. (She is.) But we also roll a Listen check for the nearby guards to see if they hear Biesta. (They don’t.)

Let’s stop there for a second, because this is our primary topic today: I rolled for the guards because I did not know what the outcome of Biesta’s snooping in the office would be. And that was true even if the PCs didn’t interfere at all.

For example, a completely different possibility is that the PCs try to break into the compound from a different direction; while they’re performing their infiltration, however, Biesta gets caught snooping and there’s a whole bunch of new activity flowing to and away from the office that they now need to deal with. Or maybe Biesta sneaking back out of the office creates a timely distraction that allows the PCs to escape. Or maybe Biesta walks in on the PCs while they’re trying to leverage Lord Abbercombe out the window.

The point is that Biesta is a dynamic element which, once set in motion, even I don’t know the consequences of.

Other GMs might want to get a little more specific in planning out Biesta’s predetermined course: They might know, for example, that (barring PC interference) Biesta will reach the office, find the shivvel, and leave without alerting a guard. In other circumstances, I might do the same thing. A lot depends on the specific needs of the particular scenario.

Think of your scenario like a billiards table: You set up the table and you let the players take their shot. Unlike a normal billiards table, though, a bunch of the balls (NPCs, etc.) are in motion when the PCs show up, and will remain in motion (probably cyclically so for the sake of easy prep) until the PCs take their shot.

(Some GMs will take this even further and ignore the interference of the PCs. I’m going to refer those GMs to the Railroading Manifesto.)

- We roll a Listen vs. Move Silently check to determine whether or not Biesta notices Tee. (I probably also rolled for the guard, but given distance and walls his success was really unlikely.) She does!

- We now roll a Hide vs. Spot check to determine whether or not Biesta spots Tee when she comes over to the window. She doesn’t, but in coming over to window and saying, “Who’s there?” she’s made enough noise that…

- We roll a Move Silently vs. Listen check for the guard to once again notice Biesta. And this time, he does!

As a result, we’ve discovered that Tee’s presence — despite being quite subtle — has resulted in Biesta being discovered by the guard. This has long-term implications, because the guard then takes Biesta to Linech: Which means that the guard closest to the office is no longer present, making the additional Move Silently checks for actually extricating the statue substantially easier for the group to succeed at. But also creates a ticking time bomb at the end of which Linech is going to come to his office to find out what Biesta was up to. (In fact, if it hadn’t been for Ranthir’s clever use of feather fall to speed up the extraction, it’s likely that Linech would have gotten back in time to catch them in the act. Careful planning is important in D&D, folks!)

This is, as I said, a rather minor interaction. But I think it offers a rather nice window into my general methodology as a GM, and also highlights the fascinating and rewarding outcomes that can result.

the character wasn’t particularly stupid or anything. But a pattern of poor rolls on very specific types of checks (across multiple skills, actually) caused this element of the character to emerge, at which point the player (and the rest of the group) took it and ran with it.

the character wasn’t particularly stupid or anything. But a pattern of poor rolls on very specific types of checks (across multiple skills, actually) caused this element of the character to emerge, at which point the player (and the rest of the group) took it and ran with it.

The things about these prophecies, though, is that they generally exist either because the author knows what they’re planning to write or, in the case of mythological history, because they’ve been retroactively created to fit events which have already happened. (Really easy to pick winners and losers a couple centuries after the fact.)

The things about these prophecies, though, is that they generally exist either because the author knows what they’re planning to write or, in the case of mythological history, because they’ve been retroactively created to fit events which have already happened. (Really easy to pick winners and losers a couple centuries after the fact.)