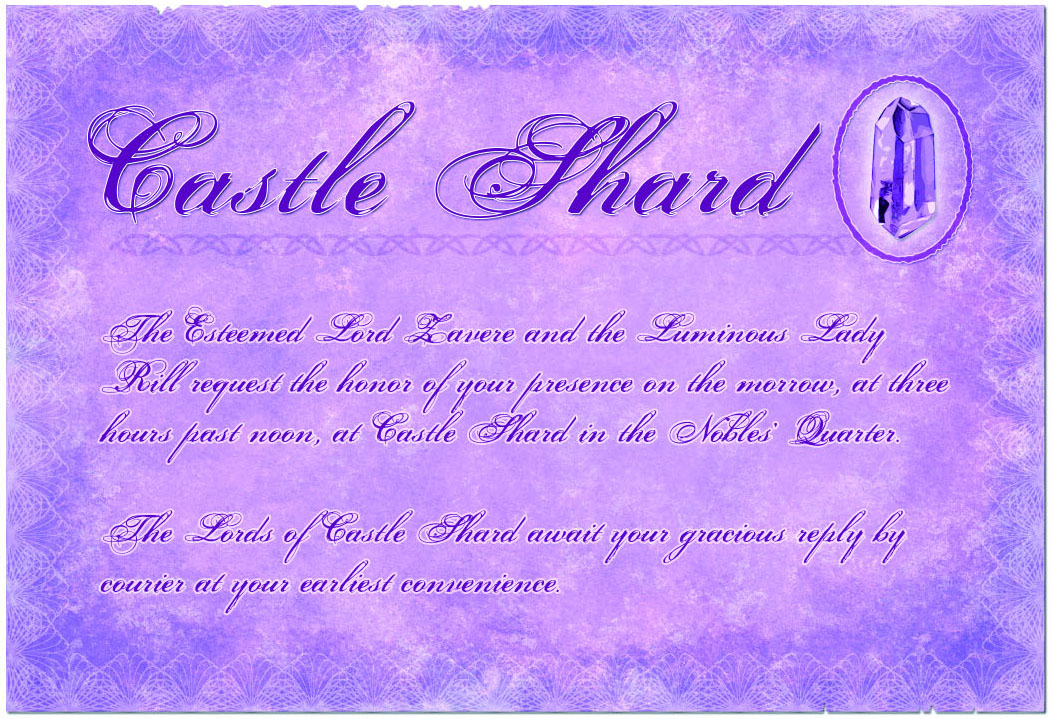

Session 12B: A Party at Castle Shard

It was not the evening that any of them had expected – it had been both more and less than that. But it was an evening that none of them would ever forget.

I’ve had a couple of people mention, when they realized what the heart of Session 12 was going to be, that they were interested in seeing what the Party Planning game structure I wrote up awhile back would look like in actual play. Unfortunately, this is one of those occasions where the nature of writing up a campaign journal entry creates something of a distortion field.

Everything that’s described in the campaign journal actually happened at the table, of course, but events have been both rearranged and heavily condensed. My goal was not, in fact, to provide a transcript of the session, but rather an effective summary that could serve as both entertainment and reference document as the campaign moved forward.

Perhaps the most significant “deception” to be found here, for example, is the degree to which the campaign journal fails to represent how much cutting back and forth there was between scenes: When the party split up and went to talk to a bunch of different people, I would engage in conversation for a couple of minutes and then swap to another group and then again and then again. These interactions have not only been boiled down to their key highlights, they’ve also generally been grouped together into complete conversations.

With this limitations in mind, however, let’s take a closer look at how the Party at Castle Shard worked in actual play.

SETTING IT UP

To start, let’s consider what the function of the party was. This was several fold, actually:

- It was a reward for their hard work. In Getting the Players to Care I talk about how one of the methods of doing that is to make it treasure. This is a somewhat unusual variant on that principle, but by making this party clearly part of the lavish pay-off for the hard work (and near death experiences) they had put in for Lord Zavere, the players became deeply invested in the party and were anticipating it for months in the real world.

- It was a signal that the PCs had risen to a new level in the world. This inherently meant closing one “chapter” of the campaign and beginning the next.

- It was an opportunity to introduce a bunch of new characters, drastically expanding the supporting cast of the campaign and setting up relationships that would drive the campaign forward into Act II (which is still a little ways down the road at this point, but which was definitely on my horizon).

It was also, of course, intended to be an entertaining evening of gaming.

THE GUEST LIST

Let’s take a moment to look at the new characters I was introducing here. There were a total of eighteen guests at the party (not including the PCs), of which five were previously known to the PCs.

Familiar Faces: The familiar faces were quite intentional. First, because it would provide islands of familiarity for the PCs to fall back upon (and around which social interactions with the new NPCs could coalesce). Second, because the PCs had been compartmentalizing the various aspects of their lives and I knew that bringing some of these aspects together (and most likely overlapping with each other) would create dramatic tension.

New Faces: Nonetheless, throwing more than a dozen new NPCs at the players all at once may seem like a lot at first glance. But the party planning structure is designed to break them up into smaller groups, and introduce them in manageable chunks.

More importantly, I’ve found that it can be quite effective to introduce a bunch of new characters in a cluster (whether all at once in a party like this or just rapidly over the course of a few sessions) and then have spans where only established characters are being reintroduced. If I was going to theorize about why this works, I would say it’s partly because some NPCs will “click” with players and some won’t, and when you introduce them in clusters your focus will naturally be drawn towards the NPCs who are resonating. (You’ll notice that this echoes, at a macro-level, something I talk about in Party Planning at a micro-level.)

But it’s also because having all of these new characters interact with and collide with each other is a great way of revealing character; and also a great way of drawing the PCs into their drama.

Stacking Interesting NPCs: The other way I think about this technique is that I’m “stacking” interesting NPCs. It’s like I’m laying in a supply. Each NPC is a tool, but you can often let the PCs figure out how they’ll actually end up getting “used” down the line.

For example, look at how the PCs pursue selling the orrery they found in Ghul’s Labyrinth here, creating a plot thread that will run for several more sessions. You’ll also want to pay attention to how the PCs’ relationship with Aoska develops in the future.

Of course, in some cases I’m planting NPCs in order to very specifically set things up in the future. The great thing is that, if you do your job right, the players won’t be able to figure out which is which. Honestly, if you do it right, then down the line you’ll probably have difficulty looking back and remembering which was which.

BANG, BANG

“Ah, Mistress Tee!” Zavere’s deep baritone called out to her. “Perhaps you could help me talk some sense into Leytha Doraedian.”

With something of a sick feeling in her stomach, Tee turned. It was true. Doraedian was standing there with Lord Zavere. He had a look of absolute surprise on his face.

Which touches on a wider design ethos: Your party has a location, a guest list, a main event sequence, and topics of conversation. If you want to create a truly kick-ass party, your primary design goal is to liberally seed all of these elements with moments of dramatic potential.

Note that I didn’t say dramatic moments. I said moments of dramatic potential. The actual dramatic moments will arise out of that potential during actual play. What you’ll find even more surprising is how these varied moments of dramatic potential will begin interacting with each in ways you never anticipated.

For example, when it came to Tee’s mentor, Leytha Doraedian, I had only a single note:

Surprised to see Tee at Castle Shard.

I didn’t know how (or even when) that surprise would manifest, exactly, but I think the dramatic potential in it is clear.

In my Topics of Conversation, I had listed:

Argument between Doraedian, Zavere, and Moynath about the Commissar’s weak attitude towards the Balacazars.

It was only as the events of the party actually played out that Tee became the character who approached this debate in progress and these two moments joined together to create the very memorable scene you see in the campaign journal. (Nor had I anticipated the way in which Tee’s earlier interactions with the Commissar would increase her own tension and confusion over this topic.)

Many of these dramatic moments can be thought of as bangs around which scenes (or mini-scenes) can be framed during the party. But others are just angles of tension (old relationships, new debates, hidden agendas), and the bang will be discovered during play as these elements interact with each other.

And some of your bangs may not ignite. For example, the Graven One has a bad history with the Inverted Pyramid and I wrote, “His cold indifference with the Inverted Pyramid will manifest itself if he interacts with Jevicca Nor.” But in the organic ebb and flow of the party, that never happened. (Which is, of course, just fine.)

In other cases, of course, the PCs will aggressively pursue agendas and create bangs (either directly or indirectly) that you had no way of anticipating. Make sure you don’t miss those moments! Pursue them aggressively!

A STRONG START

“Master Ranthir!” The Iron Mage cried, crossing the room towards him and resuming his scan of the room. “Mistress Tee! Agnarr, Elestra, and Dominic! Master Tor! To my side! I have an errand for you!”

All of this talk about discovering things during play aside, there’s no reason to be afraid of having some strong, pre-designed moments. The sudden appearance of the Iron Mage is one such  example of this: It’s a very strong bang that demands a response from the PCs.

example of this: It’s a very strong bang that demands a response from the PCs.

In many ways, this is the primary function of the Main Event Sequence: You let things play out organically, but if you feel like the current pool of dramatic tension is being exhausted, trigger the next event, which will usually be some strong, dramatic moment – perhaps accompanied by a specific bang the PCs need to react to – which will cause all the pieces of the party to suddenly move in new directions and begin a fresh set of collisions.

One place where you’ll want to make a point of stocking these ready-to-go moments is at the very beginning of the party: You want a good, strong start to set things in motion. Once you’ve got some momentum built up, the action will generally begin driving itself. But you’ve got to get that momentum going.

You can see this in the Party at Castle Shard with the opening sequence of events, which, in my notes, I actually separated out as a separate event track labeled “Arrival – Events”:

- Arrival (Kadmus greets them and leads them to Zavere’s private office; they’re eyed by other guests who are being taken directly upstairs)

- Meeting with Zavere (chance to spot the writing on the map; Zavere tells them Linech’s burrow has been destroyed; he personally escorts them to the ballroom)

- Rehobath and the Commissar (Kadmus barring their entry; a loud argument; Zavere smooths things over)

- Guests of Special Honor (Zavere introduces them as “guests deserving of much honor, for their recent service to both myself and to the interests of the City of Ptolus” in order to needle the Commissar)

This sequence introduces them to a handful of characters; gives everyone a chance to start warming up to social interactions; and gives the PCs two BIG bangs. I don’t know what their reaction to those bangs will be, but they’re pretty much guaranteed to color how the rest of the party progresses.

You can also see how I used these first moments to establish, in brief, several key pieces of exposition which would be major hubs for the rest of the party:

- Conflict between Zavere and the Commissar.

- Destruction of Linech Cran’s burrow (which could have also been learned before the party if the PCs had been seeking information, but they were stuck underground).

- The other guests are intrigued by the PCs being included on the guest list.

And, really, that’s all it takes to get the ball rolling.

And of course, sometimes you do need to draw a hard line. The One Ring isn’t the One Ring if it isn’t the One Ring; it can’t be part of a JCPenney jewelry collection.

And of course, sometimes you do need to draw a hard line. The One Ring isn’t the One Ring if it isn’t the One Ring; it can’t be part of a JCPenney jewelry collection.