DISCUSSING

In the Shadow of the Spire – Session 44A: Whorehouse of Terror

Agnarr flew into a rage. “Stay away from her!”

The serpent-men in the far hall had now thrown open one of the doors there. “Erepodi!” they shouted through it. “We’re under attack!”

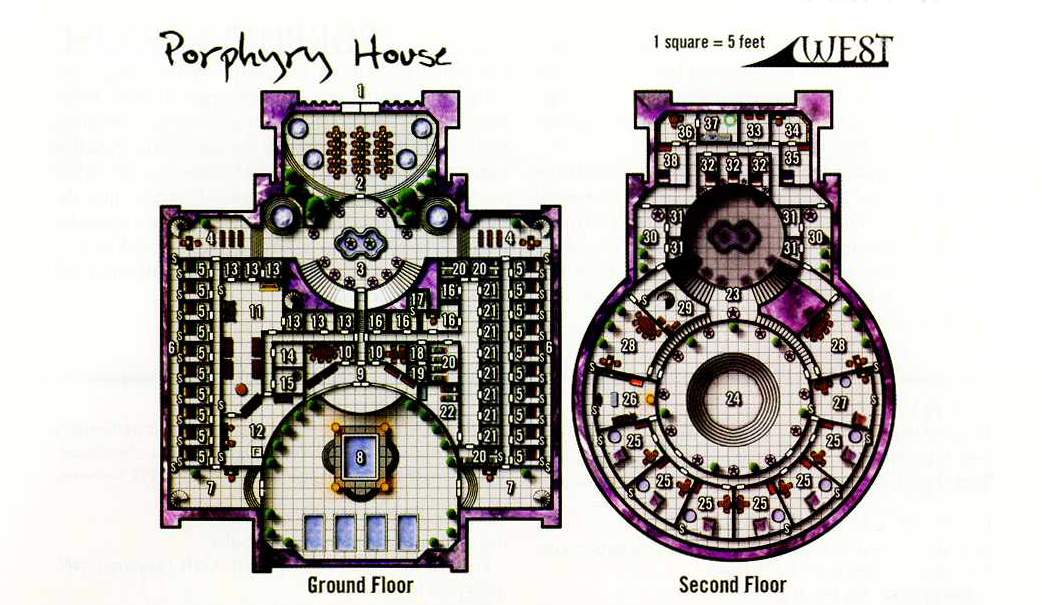

Erepodi… The name was familiar to Tee. It took her a moment to wrack her memory, but eventually she alighted upon its source: The small picture locket they had found in Pythoness House.

And indeed, in the very moment that Tee remembered the locket, Erepodi herself strode into view through the door, scarcely changed from her picture.

“I know not who you are! Or why you have come! But none shall disturb my house!”

This is a moment where the player has forgotten something that happened during the campaign. This isn’t unusual. As human beings we forget stuff all of the time, and unlike our characters we aren’t living in these fictional worlds 24-7. (Or whatever the hours, days, and weeks look like in your fantasy milieu of choice.)

I don’t remember exactly how this precise moment was resolved, but it generally happens in one of three ways.

First, one of the other players does remember this bit of continuity and simply reminds the table what happened. It’s up to the player to decide whether that’s an in-character moment (e.g., Tee forgot and Ranthir reminded her) or not. (I’m pretty confident this isn’t what happened in this moment, as this happens all the time and I wouldn’t have recorded it in the journal.)

Second, the campaign journal is consulted. Creating a record of continuity is, after all, exactly why we’re keeping a campaign journal in the first place. In the case of the In the Shadow of the Spire campaign, one of the players has loaded the journal into the group’s private wiki so that it can be rapidly searched (along with digital copies of many of the handouts and other records the group has created).

Third, I’ll have the PC make a memory check. For my D&D 3rd Editon campaigns, I simplified and adapted a rule from the Book of Eldritch Might 3 for this.

MEMORY CHECK

Whenever a character might remember something that happened to them either in actual play, from their own (pregame) past, or something that happened “off stage”, they should make a memory check. (This could also be to remember some minor detail that the DM didn’t point out specifically because it would have caused undue suspicion and attention…)

A memory check is a simple Intelligence check. Characters cannot Take 20 and retries are not allowed. (Characters can Take 10 in non-stressful situations, however.)

| DC | Situation |

| 5 | Something just about anyone would have noticed and remembered; the general appearance of the man who killed your father (assuming you got a good look at him) |

| 10 | Something many people would remember; such as the location of the tavern they ate at across town yesterday |

| 15 | Something only those with really good memories might recall; like the kind of earrings a woman was wearing when you spoke with her three days ago |

| 20 | Something only someone with phenomenal memory would remember; such as the name of a man you met once when you were six years old |

| 25 | Something no normal person could remember, such as the nineteenth six-digit combination code on a list of 80 possible combination codes for a lock, when you only saw the list for a few moments |

Characters also have access to the following feats:

- Excellent Memory: +5 to memory checks

- Photographic Memory: +15 to memory checks. (Requires Excellent Memory.)

This material is covered by the Open Gaming License.

THE GM’s ROLE

What about my role as the GM here? Shouldn’t I just tell the players when they’ve forgotten something?

Maybe.

This is a tricky bit of praxis, in my opinion. On the one hand, I don’t want the players stymied because they’ve forgotten something that their characters should remember. On the other hand, figuring out how things fit together is a deeply satisfying and rewarding experience, and I don’t want to be constantly short-circuiting that by spelling everything out for them. Conclusions are just infinitely more fun if the players figure them out for themselves.

And, in fact, it can also be fun when the players could have figured something out, but didn’t. That, “Oh my god! It was right in front of us the whole time!” moment can be really incredible, but none of you will ever have the chance to experience it if you’re constantly spoonfeeding them.

So if I can see that my players have “missed” something, the first thing I’ll ask myself is, “Have they forgotten a fact or are they missing a conclusion?” I may or may not provide them with a missing fact, but I will do almost anything in my power to avoid giving them a conclusion.

(This situation with Erepodi is an interesting example because it kind of lands in a gray area here: It’s partly about remembering a fact they learned in Pythoness House — i.e., the name “Erepodi” — and partly about drawing the conclusion that this is the same person. So it’s a little tricky.)

The next thing I’ll consider is, “Is this something that their character should remember?” The answer to that may be an obvious Yes, in which case I’ll provide the answer. If the answer isn’t obvious, call for a memory check. (This can usually just default to some kind of Intelligence or IQ check if your system doesn’t have a formal memory check mechanic.)

Tip: An advanced technique you might use, if you have a searchable campaign journal like we do, is to say something like, “You should check the campaign journal for that.” The disadvantage is that this consumes extra time. But it has the benefit that the players still feel a sense of ownership about “figuring it out.” Logically, it shouldn’t make a difference. In practice, it can be an effective bit of psychological finesse.

Another key consideration is how essential this information is to the structure of the scenario and/or the PCs’ current situation. If it’s just an incidental detail leading to a revelation that could just as easily simmer for a long time, then I might be a little more likely to let it pass and see if the players notice it or figure it out later. If, on the other hand, they’re in a middle of an investigation, are rapidly running out of leads to follow, and forgetting this detail will likely derail the investigation completely, I’m more likely to default to giving them the info.

A final factor here is if the players are directly asking for the info. For example, if they say something like, “Erepodi? That name sounds familiar. Justin, where have we heard that name before?” This is a very strong indicator, and I’m almost certainly going to either point them in the right direction (“check the campaign journal” or “do you still have that letter from the duke?”), call for a memory check, or simply give them the information.

Conversely, if they aren’t saying anything, players often know more than you realize. It’s not unusual for me to call for a memory check, have it succeed, and give them the information, only for the player to say, “Oh, yeah. I already knew that.” This is another reason why, in the absence of other factors, I’ll usually default to not saying anything and seeing how things develop through actual play.

If nothing else, when they realize their mistake, it will also encourage the players to keep better notes!

ADVANCED TECHNIQUE: DELAYED RECALL

Here’s a technique I haven’t actually used, but by sheer synchronicity I was reading through Aaron Allston’s Crime Fighter RPG this week and stumbled across a cool idea. In the introductory scenario “New Shine on an Old Badge,” the PCs are tracking down a criminal who turns out to be an ex-cop dressing up in his old uniform. When the PCs have an opportunity to catch a glimpse of this fake/ex-cop from a distance, Allston recommends:

As the investigation and paperwork continues, the characters will find that no one knows who the officer was. Let the characters make INT rolls. If anyone achieves a 17 or better, he’ll remember who the guy is — “Ray Calhoun — only that can’t be right, because he retired six or seven years ago; he used to visit the station pretty regularly, even after he retired.”

If someone achieves a fourteen or better, he’ll wake up in the middle of the night remembering who the guy is.

Emphasis added.

In this case (pun intended), this isn’t something the players have forgotten or would be capable of remembering. (Their characters met Ray Calhoun before the campaign began.) But the idea of taking a partial success and resolving it as, “In the middle of the night you wake up and realize you forgot something!” is, I think, a really interesting framing for this.

Along similar lines, you might decide, “Well, they don’t immediately remember encountering the name ‘Erepodi’ before. But the next time they encounter the name, it will all fall into place for them.”

CONCLUSION

Some of the issues you’ll run into with player memory vs. character memory will be very similar to the issues that can arise when adjudicating idea rolls. For a deeper discussion on those, you might want to check out GM Don’t List #10: Idea Rolls.

Campaign Journal: Session 44B – Running the Campaign: Adversary Rosters in Action

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index