Tagline: The world of Tékumel is an exciting, interesting, richly detailed setting almost without equal in the realms of fiction (roleplaying or otherwise). It has been plagued with a bad publication history, but nonetheless has become legendary in the RPG community for its positive aspects.

This is the first review in a series of reviews designed to cover the Tékumel setting in a great deal of depth. Although there’s no strict schedule on which these reviews will be turned out, by the time I’m done I hope to have been able to cover all of the major Tékumel products which have been published over the past two and half decades since it first appeared in print, along with a good sampling of the minor ones. This review, therefore, is a little bit different than most – it will be a protracted look at the history of the Tékumel setting (an overview of the Tékumel setting, publishing history, and other miscellaneous information), serving as a general introduction to the product-specific reviews which will follow.

THE SETTING

The world of Tékumel was first settled by humans exploring the galaxy about 60,000 years in the future, along with several other alien species. They did massive terraforming of the inhospitable environment, disrupting the local ecology and banishing most of the local fauna (including some intelligent species) to reservations on the corners of their new world. This was a golden age of technology and prosperity, even on one of Mother Earth’s colony worlds.

Then the world got dropped into a dimensional pocket. Don’t you hate it when life rains on your parade?

In any case, Tékumel was severed from the interplanetary trade routes and went through a massive gravitic upheaval which threw civilization into chaos. The native species broke loose from their reservations and civil war seized the planet. Several other significant changes took place due to the crisis – mankind discovered it could now tap into magical forces, the stars were gone from the sky, dimensional nexi were uncovered and pacts with “demons” (dimensional travelers) were made, a complex pantheon of gods was discovered, and science began to stagnate and the belief that the universe was understandable slowly faded. A Time of Darkness descended over the planet.

In any case, Tékumel was severed from the interplanetary trade routes and went through a massive gravitic upheaval which threw civilization into chaos. The native species broke loose from their reservations and civil war seized the planet. Several other significant changes took place due to the crisis – mankind discovered it could now tap into magical forces, the stars were gone from the sky, dimensional nexi were uncovered and pacts with “demons” (dimensional travelers) were made, a complex pantheon of gods was discovered, and science began to stagnate and the belief that the universe was understandable slowly faded. A Time of Darkness descended over the planet.

Which brings us to a much later time period and the world of Tékumel as it has been revealed to us through the writings of Professor M.A.R. Barker – specifically the area of the Five Empires on Tékumel’s northern continent.

The Professor (as he is affectionately referred to by people who don’t like typing out “M.A.R. Barker”) developed Tékumel in much the same way that J.R.R. Tolkien developed the much more popularly known Middle Earth (setting for The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings). His interest in myth and languages lead him to develop his own fantasy languages based upon fantasy cultures in a fantasy world influenced heavily by his studies in myth. The difference is that where Tolkien drew largely on the northern European myth structures, the Professor’s interests lay largely in the languages and myth structures of India and Southern Asia.

What distinguishes Tékumel even more from Tolkien is the media in which it was presented to others. Tolkien, after years of dabbling in his fictional world, eventually wrote two major novels and a series of other works set there. M.A.R. Barker, on the other hand, was a professor at the University of Minnesota at the same time that Dave Arneson, Gary Gygax, and a handful of others were developing the first “roleplaying games”. This was the tradition which the Professor would tap into to explore and develop his own games. His “Thursday Night Groups” were some of the first roleplaying sessions anywhere, and quite possibly the first non-D&D ones ever. This unique, week-by-week, thirty year development of the world on a very personal level is unknown to any other detailed fantasy world of this calibre.

First, you have the hyper-detailed languages. Tsolyáni, one of those languages, has had grammatical guides, dictionaries, and even a language course developed for it (Tolkien’s languages and Star Trek’s Klingon are the only serious parallels to this type of development). In order for these languages to have that type of deep accuracy, the Professor developed wholistic cultures, histories, dress fashions, architectural styles, weapons, armor, tactical styles, legal codes, demographics, and much else.

Second, you have the religions of Tékumel. There are a (relatively) small number of true gods and goddesses in Tékumel; but they are far beyond our comprehension. Instead each religion worship specific aspects of these gods and goddesses in different forms – with different degrees of specificity (Lesser and Greater Aspects) and spheres of influence. It is heavily inspired by the mythologies of India and Southern Asia (as is the rest of the world’s background), and utterly unlike anything else I’ve seen published in the fantasy genre in terms of depth, understanding, consistency, and originality.

Third, the cultures which have been created (which, as noted above, grew out of the myth and language Barker was developing) are rich, alien things. They are extremely baroque, being based along the classical lines of the Indian, Chinese, and Japanese cultures. They envisioned on a grand, epic scale and are possessed of breathtaking qualities.

Finally, the day-to-day development of the world has resulted in all of these intricately details being put into a constant motion which have resulted in unique developments and depth. This is a world of intricacy and complexity almost unmatched.

Tékumel is one of the most intricately detailed and believable fantasy worlds ever created – one of the “Big Three” in my mind (a list made up of Middle Earth and Tékumel, with Harn coming in at a slightly distant third place).

THE PUBLISHING HISTORY

There are some who theorize that the extremely alien qualities of Tékumel as a setting are what have resulted in its disappointing history – one of limited commercial success, despite a fervent and committed following. Personally I think we are putting the cart before the wheel somewhat here; the publishing history of Tékumel has been one marked with troubles. I think these troubles are the cause of Tékumel’s limited commercial success, not its result.

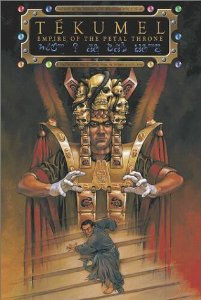

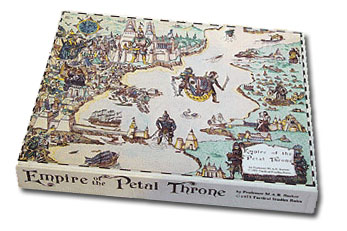

Tékumel first burst upon the scene in 1975, when TSR (still known as Tactical Studies Rules) published it as a standalone game under the title of The Empire of the Petal Throne (“Empire of the Petal Throne” being a euphemism for the Tsolyánu Empire). Despite some of the moral and ethical warping of the world brought about Gygax pasting on an AD&D-style alignment system, Empire of the Petal Throne met with a great deal of critical and financial success. It brought a level of detail and quality to the world in which a game was set which had previously been unknown in the RPG industry (this was still several years before the first major concordance of Greyhawk would appear). It was a turning point away from the tactical roots of RPGs and towards the unique possibilities this new medium was capable of providing.

Tékumel first burst upon the scene in 1975, when TSR (still known as Tactical Studies Rules) published it as a standalone game under the title of The Empire of the Petal Throne (“Empire of the Petal Throne” being a euphemism for the Tsolyánu Empire). Despite some of the moral and ethical warping of the world brought about Gygax pasting on an AD&D-style alignment system, Empire of the Petal Throne met with a great deal of critical and financial success. It brought a level of detail and quality to the world in which a game was set which had previously been unknown in the RPG industry (this was still several years before the first major concordance of Greyhawk would appear). It was a turning point away from the tactical roots of RPGs and towards the unique possibilities this new medium was capable of providing.

The game was loosely supported in Dragon magazine for awhile, but eventually it died from lack of major support by TSR (which was already beginning to focus exclusively on the D&D franchise, with the new AD&D game being just around the corner). The setting was supported for several years by its adherents (including the participants in the Professor’s own games) in various forms, including several sets of miniature rules.

The next major landmark in the history of Tékumel publishing is when the company Gamescience published a Sourcebook and a Player’s Handbook in 1983 – essentially a two volume set of background and rules (the latter being completely different from the earlier rules in Empire of the Petal Throne). This system remained entirely unsupported (Gamescience went out of business among other things), although the setting continued to be — most notably with the Armies of Tékumel series (which, self-obviously, detailed the various armies of the various empires) and The Tsolyáni Language (which, self-obviously, detailed the Tsolyáni language in detail for the first time).

In 1987 a company known as Different Worlds proceeded to reprint the Gamescience manuals – but in the process managed to confuse everyone thoroughly by breaking up the Sourcebook into multiple volumes (Books 1-3, each published in a separate volume) and then going out of business before publishing Book 3 of the Sourcebook or any of the Player’s Handbook.

In 1987 a company known as Different Worlds proceeded to reprint the Gamescience manuals – but in the process managed to confuse everyone thoroughly by breaking up the Sourcebook into multiple volumes (Books 1-3, each published in a separate volume) and then going out of business before publishing Book 3 of the Sourcebook or any of the Player’s Handbook.

Then, in 1992, a company known as Theatre of the Mind (TOME) started publishing a series known as The Adventures of Tékumel — which was, yet again, completely different from any previous ruleset. If you thought Different Worlds made things confusing with their books, TOME was even worse. First, Adventures of Tékumel: Part One was published as a single book. Then Adventures of Tékumel: Part Two was published in three different volumes. Finally, TOME published Gardásiyal: Deeds of Glory as a stand-alone set of rules. This was confusing because, first, “Deeds of Glory” was the name for an old set of Tékumel miniature rules, and, second, because Gardásiyal wasn’t really a complete game – you needed the character creation rules from Adventures of Tékumel: Part One (but nothing from any of the Adventures of Tékumel: Part Two volumes). On top of it all, Gardásiyal isn’t particularly good at describing the world of Tékumel – so the old Gamescience sourcebook is still heavily recommended.

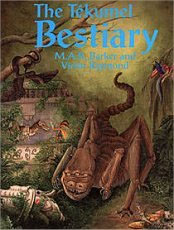

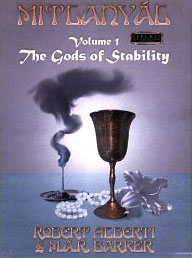

Nonetheless, TOME represents the most continuous and in-depth publishing history for Tékumel yet (with the exception of auxiliary publications by Tékumel Games, which is directly connected to the Professor) – they have produced a Tékumel Bestiary and will, hopefully, be publishing Mitlanyál (a guide to Tékumel’s gods and religious structures) in the near future.

One of the interesting things to note (in a sort of macabre fashion) is that as the roleplaying industry moves towards simpler and more intuitive systems, the systems published for use with Tékumel have become more and more complicated, archaic, and non-intuitive. This is ironic, because the Professor himself uses an almost diceless homebrew.

One of the interesting things to note (in a sort of macabre fashion) is that as the roleplaying industry moves towards simpler and more intuitive systems, the systems published for use with Tékumel have become more and more complicated, archaic, and non-intuitive. This is ironic, because the Professor himself uses an almost diceless homebrew.

There’s some other miscellaneous stuff that should be mentioned. The Blue Room FTP site (dealt with in more detail below) has offered some shareware manuals. Tirikelu is a set of shareware roleplaying rules produced by a fan. Conversions for Tékumel exist for GURPS, AD&D, RuneQuest, TORG, and quite probably others as well that I am forgetting of. And I have not even delved into the miniature rules, the vast majority of the supplements, the maps, or the miniatures… not to mention the novels (which is where the next review will be taking us).

As you can see its a bit of a tortured history. That is one of the reasons why I’m producing this series of reviews – so that you know what each product contains and can figure out for yourself what would be the best way to get into Tékumel.

OTHER INFORMATION

For those of you interested in discussing in Tékumel there are two major ‘net-based discussion groups: The Tékumel newsgroup (alt.games.frp.tekumel) and the Blue Room mailing list. To subscribe to the mailing list (which the Professor participates on) send e-mail to Chris Davis (the list’s moderator) at blueroom@prin.edu.

Those of you interested in tracking down Tékumel material may find it difficult. However, Tita’s House of Games (run by Carl Brodt) has become a one-stop source for the material (both in print, OOP, and reprint material). His catalog is routinely posted to the alt.games.frp.tekumel newsgroup. You can also get a catalog with the following contact information:

Those of you interested in tracking down Tékumel material may find it difficult. However, Tita’s House of Games (run by Carl Brodt) has become a one-stop source for the material (both in print, OOP, and reprint material). His catalog is routinely posted to the alt.games.frp.tekumel newsgroup. You can also get a catalog with the following contact information:

E-mail: CarlBrodt@aol.com

Snail Mail: 1608 Bancroft Way; Berkeley, CA 94703

Phone: (510) 848-3260

There are also a number of web-based resources for the setting:

Brett Slocum’s Tékumel Page

http://www.skypoint.com/~slocum/tekumel

Mr. Slocum’s page, while not the most visually smashing thing you will ever see, is professionally put together in a format where it is easy to find exactly what you’re looking for (something which I wish could be said of all web designers). The site is packed full of useful information – including the Tékumel FAQ, Publishing History, a setting overview, maps, timeline, a GURPS conversion, and links to many of the sites found on this list as well as links to other resources (including other conversions and freebie rule sets). If you can only go to one Tékumel website, this is the one it should be.

Tékumel: The World of the Petal Throne

http://www.tekumel.com

Designed by Peter Gifford this site is visually dazzling, while not falling prey to bad web design as a result. It is showing great potential with its own content, and has links to much of the on-line content it doesn’t possess. Highly recommended.

The Blue Room FTP Site

ftp://nexus.prin.edu

As noted above, Professor Barker participates on the Blue Room Mailing List. Chris Davis (the Room’s moderator) has also established this FTP site – which contains some Tékumel-related documents authored by Barker and others. I hope to eventually review several of these web-only products eventually, but in the meantime you should take a look for yourself.

The Jade Arch

http://www.interlog.com/~maliszew/jade.html

The Jade Arch gets mandatory mentioning here because its designer, James Maliszewski is one of the columnists here at RPGNet. Plus it has an interesting game-related focus (rather than the world-related focus of most other sites).

Empire of the Petal Throne Products

http://www.halcyon.com/www2/bwr/ept_list.html

This product listing is one of the best available, listing everything (to my knowledge) that has ever been published for Tékumel in any format.

There many other sites out there, but this is a good sampling of most of it. Since between the first three sites on the list you should be able to find links to everything else, this is a good jumping off point for you.

CONCLUSION

Tékumel is a world almost without equal. Its publication history has made it difficult to track down serious material for it, though. Knowing which books to buy, and in which order to buy them, is not particularly easy. Fortunately, Tita’s House of Games (described above) has made actually getting the material much easier.

Although I know some who have given up on this rich gaming environment because of these difficulties, I hope that this series of reviews will serve to guide you back into it. And for those of you who have not yet experienced this piece of gaming history, I hope to light a passion in it for you. It’s well worth the effort.

For those of you reading this after it has been placed in the archive and interested in reading the series in sequence, the next review will be of the novel Man of Gold.

Style: 4

Substance: 5

Author: Professor M.A.R. Barker

Company/Publisher: Various

Cost: n/a

Page count: n/a

ISBN: n/a

Originally Posted: 1999/07/19

I never actually completed the intended series of Tékumel reviews. The series ground to a halt after hitting the first two novels (Man of Gold and Flamesong). The publication history related in this review is now incomplete, of course, but Empire of the Petal Throne unfortunately remains a blighted intellectual property. Its next major publication was Tékumel: Empire of the Petal Throne, a Tri-Stat game published by Guardians of Order… just in time for Guardians of Order to go bankrupt and close its doors. A company called Zottola eventually managed to get Mitlanyál and a couple new novels into print, but they went out of business in 2011. Tita’s House of Games is supposedly still around, but the site hasn’t been updated since 2010.

M.A.R. Barker himself died just over a year ago. Before he died, he founded the Tékumel Foundation to preserve the legacy of his work… but they also haven’t updated their website in years.

The lengthy (and, to date, futile) struggle to have Tékumel published in a coherent, unified format for any significant period of time remains a source of great sadness for me, particularly as I reflect on both the travails of Legends & Labyrinths and my ongoing work to preserve and promote the literary legacy of my mother.

Maybe someday….

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.