Tagline: Although often lost in the shadow of her big brother Heavy Gear, Jovian Chronicles is a great game in its own right. The Silhouette system is every bit as powerful as it ever was, and the setting — a future version of our solar system — intriguing, layered, and (literally) exploding with potential.

Dream Pod 9 has produced and supported three primary games. The first of these, their flagship, is Heavy Gear has been almost universally praised. The second, Tribe 8, has carved out a place for itself as one of the finest and most original fantasy games in the roleplaying industry.

Dream Pod 9 has produced and supported three primary games. The first of these, their flagship, is Heavy Gear has been almost universally praised. The second, Tribe 8, has carved out a place for itself as one of the finest and most original fantasy games in the roleplaying industry.

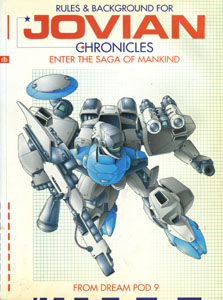

Their third game, however, has not been quite so fortunate. Jovian Chronicles, like her big brother Heavy Gear is a mecha game using the Silhouette rules system and inspired, at least partially, by anime. As a result, Jovian Chronicles has often found itself lost in Heavy Gear’s shadow.

It doesn’t deserve to be.

Although there are many similarities between the games, there are also many differences. In Heavy Gear, for example, the mecha are suits of powered armor in completely alien setting far in the future, driven by an overarching meta-story and set of intriguing, deeply developed characters. In Jovian Chronicles, on the other hand, you have a hard SF world in which the mecha serve as space fighters in a setting close to home, both spatially and temporally.

Both Heavy Gear and Jovian Chronicles are remarkably strong games, and both would be in my Top 10 list for the industry. But they are there for different reasons.

THE SETTING

At a basic level a setting can be either good or bad. In general you can characterize a good setting as one based upon interesting concepts, with a great deal of depth, detail, and originality. In general you can characterize a bad setting as one which lacks an interesting concept and is either shallow, poorly developed, lacking in originality, or a combination of all of the above.

That much is simple.

A more interesting question is what separates a good setting from a superb one.

For example, why is it when I read the setting material for Deadlands or Vampire I think to myself, “Wow, that was really good!” But when I read Heavy Gear or Trinity I’m, literally, blown away? What makes one good and the other great?

After thinking about this for a long while, I’ve decided that the primary difference lies in breadth and versatility of the setting. For example, when I read Deadlands I think to myself, “Wow, there’s a near fantasy version of the Old West, with the PCs playing western heroes. Cool.” When I read Vampire I think, “Wow, there’s a really neat modern gothic setting, in which the PCs will be playing vampires.”

When I read of Terra Nova (the world Heavy Gear is set in), however, I think to myself: “Wow, what a great world.”

In Vampire I play a vampire. In Terra Nova I can play a cop, a vigilante, a gear pilot, a spy, a terrorist, a freedom fighter, or any one of a dozen different things. As a GM I can design a campaign around, literally, dozens of completely different hooks. And all of this takes place in a richly developed world, with many different, unique cultures and political units.

Of course, you have a great deal of variety within, for example, the World of Darkness as well (particularly as you start picking up additional games and supplements), but the setting as presented in Vampire is clearly designed for the PCs to play vampires within a very specific type of campaign structure (although I would be the last to say that there isn’t a tremendous amount of variation possible within that basic structure). This isn’t a bad thing (far from it), but only a fool would say that the World of Darkness as presented in Vampire is comparable to Terra Nova as it is presented in Heavy Gear.

Which brings us back to Jovian Chronicles, which possesses all of the strengths of Heavy Gear in this regard.

The fictional timeline of Jovian Chronicles begins in 1999 (the original game was published in the early ‘90s), when the Solar Power Satellite 1 is successfully tested. By 2002 mankind has established their first permanent space station (which is true, although in the game it has the fictional name of “Freedom Station”). In 2007 a prototype fusion engine successfully generates power. Technology and space exploration begins to advance rapidly and by 2024 the moon is colonized. (For those of you gasping with incredulity at this point, the designers are fully cognizant of the fact that, without a minor miracle, there’s no way for a major space presence to be established inside of twenty years as Jovian Chronicles postulates. They stretched the facts slightly in this regard so that they could have an advanced spatial civilization in a future which was not so far distant as to render humanity completely unrecognizable culturally.)

In 2030 major development on orbital stations begins; in 2033 Mars is settled for the first time; in 2037 the Jovian Gas Mining Corp. is founded and the first station in Jovian orbit is built; the New Earth Project begins to terraform Venus in 2072.

And then “something bad” happens.

Social economic pressures cause several nations back home to collapse and people begin to flee Mother Earth in a massive exodus (during which Venus is settled for the first time). As chaos seizes the homeworld, Mars seizes its independence (the first stellar colony to do so). Then, in 2100, Earth disappears – rumors of major disasters and civil conflict fill the solar system, but any and all shuttles sent to investigate are destroyed. The colonies are completely cut off.

This period of isolation lasts for nearly a hundred years. In the colonies, much of this time is spent trying desperately to make themselves reliably self-sufficient; back on Earth civil war rages. Then, in 2084, the Central Earth Government and Administration (CEGA) gains control of a significant portion of Earth’s surface as the Unification War ends. As Earth extends back out into the solar system, an era of peace ensues.

But such peace cannot be sustained for long. CEGA longs to return Earth to its position as the center of humanity, while the colonies (after a hundred years of independence) squabble among themselves and no longer recognize any such thing to be true. By 2210 war seems almost inevitable…..

In the year 2210 the Solar System looks something like this: Mercury, Venus, Mars, and Jupiter are all major colonies. CEGA controls much of Earth (except for the Non-Aligned States), the orbital stations in Earth orbit, and the colonies on the moon. The asteroid belt has become a sort of “wild frontier” where those unwilling or unable to live under an organized government live in small settlements. In trans-Jovian space are the Outer Realms – dominated mainly by small research stations and the THC Corporation, which exploits the chemical riches of Saturn’s moon Titan.

Mercury. Mercury, the hottest planet in the solar system, was settled in order to provide raw resources to the New Earth project which terraformed Venus. It expanded in the 22nd century as disaffected Venusian colonists left to start new lives for themselves. Today it is home to the Merchant Guild. The guild served as the primary transport of goods and services in the solar system following the Fall. Because Mercury is entirely reliant upon the success of the Guild for their own survival, they have become friends of everyone and enemies of none… although that might change if CEGA’s “manifest destiny” begins to conflict with their own vision.

Venus. The New Earth project began the terraforming process of Venus in 2072. In the time leading up to the events of the Fall, many businesses back on Earth realized that hard times were ahead – and left for other places. Several migrated to orbital stations, but many came to Venus. In the world of 2210, the society of Venus is the result of the mixing of the corporate cultures of Asia, North America, and Europe – with a heavy influence from the Japanese. It is controlled, behind the scenes, by the manipulative Venusian Bank – which now attempts to spread its influence throughout the solar system. Many believe that Venus largely controlled CEGA for many years, but now the puppet may be getting out of control.

Earth. After the events of the Fall and the Unification War, Earth is split into two parts – CEGA and the Non-Aligned States. CEGA has expansionist plans for the solar system at large, and earthers in general have a hard time understanding that their brethren in the colonies no longer bear as much love for the birthplace of humanity as they once did. Earthers see a manifest destiny for Earth, to bring all of humanity under its control once again and CEGA leads the charge. Many wonder, however, how long CEGA will tolerate dissension at home as well as abroad.

Orbitals. Some of the earliest space stations, the O’Neill stations in Earth orbit are home to millions of people. They are once more under the control of CEGA, but were independent during the period of the Fall. The Orbitals are a melting pot, with almost every cylinder having its own Earth-derived culture and traditions.

The Moon. Like the orbitals, the moon is under CEGA control. There are several Lunar cities, with a total population of about one million. The Selenites, during the Fall, adapted themselves to the hard realities of self-sufficiency. They possess a very Puritan work ethic as a result, with creativity and imagination discouraged in favor of doing the work necessary to stay alive.

Mars. After years of war, Mars has become split in half by a tense cold war. On one half is the Martian Federation, a totalitarian state which has sided with CEGA (although it possesses some doubts now, based on the recent destruction of Mars’ orbital elevator with possible CEGA involvement, see below). On the other is the Martian Free Republic, which tends to support the Jovians.

Asteroid Belt. The belt has become home to those who choose or need to remove themselves from society. Home to countless bases formed by hollowing asteroids (with an economy often based in mining), most of the belters possess a distinct “frontier” culture. The rest of them are isolationists and fantatics.

Jupiter. As the title might suggest, Jupiter is meant to be a primary focus of the Jovian Chronicles game. The Jovian Confederation joins together three distinct states – Olympus (in Jupiter’s orbit itself, with the capital colony of Elysee itself), and the two Trojan States (Vanguard Mountain and Newhome) located at Jupiter’s lagrange points. Although all of these bases orbit Jupiter, it should be noted that they are (literally) millions of kilometers apart… with all the logistical nightmares (particularly in defense matters) that this would suggest. Quite accidentally, Jupiter has become one of the two major powers in the solar system (with CEGA) being the other. They are the only ones with an existing military capable of meeting CEGA on the figurative battlefield, and they are the only ones with the political clout to possibly avoid that bloodshed. Tensions run high between these two powers.

The setting, as you can see, is a rich one (particularly once you begin to add in the complex and dynamic interactions which exist within and between these general groupings) – with many different places to set a campaign, and even more hooks on which to base a campaign. I haven’t even begun to skim the surface of the setting (leaving out details such as Titan, the United Space Nations, SolaPol, and the mystery of the Jovian floaters). It is easily one of the best roleplaying settings you will find. Indeed, I will say that, like Terra Nova, it is one of the best settings period — in or out of the roleplaying industry.

With all that being said, the setting of Jovian Chronicles as presented in the core rulebook does have two relatively serious problems. To explain the first of these, I must first delve into a digression.

A setting can be crippled not just through a lack of information, depth, campaign hooks, or originality. It can also be crippled by the lack of specific information.

Take, for example, the first printing of Trinity. This setting contained a massive number of potential campaign hooks – the proxies who controlled the psi orders were obviously engaged in their own personal machinations; the Aberrants who had devastated Earth a century before had returned; the mystery behind the disappearance of the Upeo wa Macho (the psi order of teleporters) had never been solved; Earth was going back out to reclaim their lost colonies; and the various alien species were engaged in their own plottings. These campaign hooks were backed up with a wealth of detailed information, a rich history, and an engaging, original universe. Unfortunately, there was one thing missing: The keys to unlock this vast treasure trove. Specifically, the original printing of the Trinity manual lacked information on who the proxies were and what their goals were; why the Aberrants had returned; why the Upeo wa Macho had disappeared; what had happened to the colonies during the years they had been lost; and what the aliens wanted.

Without these “keys”, the Trinity setting was fantastic – but you couldn’t do anything with it, unless you waited for the supplements to be released or were willing to abandon the two things which make using a published setting over one you’ve created yourself worthwhile: the ability to take advantage of published material and the fun of exploring someone else’s creation. (It should be noted that the paperback release of Trinity corrected this problem; the added text can be found on White Wolf’s website.)

Jovian Chronicles does not suffer from such a widespread, universal problem. However, there is one very important “key” which the book lacks. The main rulebook is set in 2210, a few weeks after an event known as the Odyssey. The Odyssey started when a group of Jovian agents were sent to Venus in order to liberate and give asylum to a Terran scientist who had perfected a “cyberlinkage” system. Their efforts to get him safely back to Jupiter spanned the solar system, and resulted in the destruction of Copernicus Dome on the Moon and the orbital elevator on Mars. One of the major Jovian colonies also came near destruction before the entire incident came to an end.

The Odyssey has had massive repercussions on the world of Jovian Chronicles, and things seem to be spiraling rapidly towards war. That makes for a very exciting game setting…. It is also creates the problem we’re discussing. To whit, the setting material in Jovian Chronicles makes it abundantly clear that things are developing very rapidly in this world – within a matter of days or weeks, literally, the solar system could be at war. The situation you’re left with is one in which, if you start a campaign, you’re just not sure when the events of your campaign are going to begin to supercede future supplements. This problem was compounded as Dream Pod 9 began pouring the majority of their efforts into the Heavy Gear product line, and Jovian Chronicles languished without support.

Fortunately, the release of Jovian Chronicles product has recently seen an upswing in support, and the next couple of years look particularly bright for the line. Further, you shouldn’t consider this a crippling flaw by any stretch of the imagination – the great diversity and breadth of the setting make up for the lack in this one particular area. Due to the depth of material presented it is also relatively easy to start a campaign in the pre-Odyssey state of the setting, and thus give yourself a little bit more breathing room.

The second problem is connected to this one, but requires me to go off on another digression: Jovian Chronicles was originally released as a licensed supplement to R. Talsorian’s Mekton game. One supplement was released, the Europa Incident. It was here that the events of the Odyssey were detailed for the first time. The Silhouette version of Jovian Chronicles reviewed here wouldn’t be released for a few more years.

The problem is that the Odyssey simply isn’t adequately explained in this book. It gets a four paragraph description on the first true page of game information, and then bits and pieces of it are referenced throughout the rest of the setting information (mainly in terms of telling you how people, places, and policies have been effected by different facets of the Odyssey). But the pieces don’t always match up, and are almost never explained.

This is frustrating, and I finally put my finger on why: Reading the details of the Odyssey in this core book were like reading a supplement. The same way in which, while reading a module set in the Forgotten Realms, you are expected to know where the Sword Coast is, this supplement expected you to know the Odyssey in quite a bit of detail (even though they did supply the summary).

But, again, a minor problem. Overall, as I’ve noted, the setting is going to knock your socks off, so let’s close on a positive note: The creative team down on Dream Pod 9, once again, display the loving detail which they are willing to put into a setting. A good example of this is found in the equipment chapter, where money is given an extensive explanation, complete with a basic primer of the economic underpinnings of the capitalistic system of 2210 (some of you are yawning, others of you have realized how important this information might be in, for example, a campaign where the PCs portray traders). It also shines through when, instead of just detailing a generic “first aid kit” or “sleeping drug”, the authors take the time to detail specific brands for the various equipment types, complete with some suggestive guidelines on how the GM can design their own brands.

It’s this type of attention to detail, in addition to envisioning broad, epic strokes for the setting, that have made Dream Pod 9’s campaign settings the industry standard in recent years.

THE SYSTEM

Jovian Chronicles uses the Silhouette Engine – so named, the designers tell us, because it “evokes many things that they hoped to build into the rules. A silhouette is simple; so is the game system. A silhouette marks the outlines of an object; the rules outline the game, helping to give form and definition to all situations. A silhouette is a shadow as a game system should be, to the point where players are not aware of it any more. A silhouette is flexible and can change shape; so can the rules.”

The motif of the silhouette, as it is described here, is certainly a model which all game designers should aspire to (with the exception of the simple part, everyone knows somebody who likes a complex engine). The game designers down at Dream Pod 9 carry through on their promises – delivering a simple, easy-to-learn system, with a ton of potential.

It should also be noted that the Silhouette System is unique in that it functions both as a roleplaying engine and a fully functional tactical engine. The two systems are completely compatible, with a simple scale change operation, and, thus, allow for a number of interesting campaign types.

The Silhouette System was introduced with the first edition of Heavy Gear, in 1995. Jovian Chronicles followed it in early 1997, with several modifications. In late 1997, the second edition of Heavy Gear was released, modifying the version of Silhouette found in Jovian Chronicles. Finally, Tribe 8 was released last year, 1998.

The primary differences between these versions of the Silhouette engine lie in the skill list, the tactical game, and the vehicle construction system. Functionally, the engine is basically identical in all its iterations, although minor things have been twitched here and there.

The basic mechanic is a dice pool (but one which doesn’t suffer from the usual statistical vagaries). Specifically you roll xd6 and take the highest number rolled. If multiple sixes are rolled, you add 1 for each additional six. If all the dice come up as 1’s, you have fumbled. Unless you fumble, you compare your final number to the assigned Threshold (difficulty) for the action – if the result is higher than the Threshold, then the character has succeeded.

So, for example, if you roll 3, 4, and 6 your total would be 6. If you rolled 2, 6, and 6 your total would by 7 (6 + 1).

In your basic skill test your skill determines the number of dice you roll, and your attribute acts as a modifier to your final result. For example, if you had a skill of 2 in Swimming and a Fitness attribute of 2, you would roll 2d6 and add 2 to the final result.

The only problem with this system is that higher levels of attributes end up contributing a lot to the resolution process, while higher levels of skills contribute less. I, personally, don’t have a problem with that – since I tend to run more heroic type campaigns (where a person’s natural talents are at least as important as what they’re skilled at), but that won’t cut it for everyone. Michael T. Richter, who occasionally posts reviews here on RPGNet, has suggested that changing the resolution system to a d8 base (with no other changes) would solve the problem.

CHARACTER CREATION

Character creation in Jovian Chronicles is a five-step process – the first of which is conceptualization and the last of which is simply purchasing equipment. The three steps in-between are “Select Attributes”, “Select Skills”, “Calculate Secondary Traits”. Character creation is thus a very simple process, but it is also a very dynamic one.

This is a good point to mention another strength of the rules specifically: Dream Pod 9 takes a lot of effort to try to make these games all things to all people. To accomplish this they provide a multitude of options, this crops up most notably in character creation with the GM’s decision to set the campaign at a “gritty”, “adventure”, or “cinematic” level. This controls the number of points which players get to create their characters, and the differences between the campaign types is discussed elsewhere in the rules.

The nice thing is that all of these options are kept simple and unnecessary – for example, specialized rules are provided for creating low-gee characters, but it’s a special option so that there’s no need to use it. You can use these extra tidbits as you want, or ignore them as you want. Dream Pod 9 has been very careful to keep the core of the system streamlined, and to make sure that everything else is a simple module that can be plugged in or left unplugged at the GM’s discretion. It gives you, as the gamer, a tremendous amount of power without burdening you with a lot of responsibility.

Select Attributes. Silhouette character creation is point-driven, but the points are split into two pools – one for attributes and one for skills. Unspent attribute points can be converted into skill points, but not vice versa.

The attribute points are spread across eight attributes: Agility, Appearance, Build, Creativity, Fitness, Influence, Knowledge, Perception, Psyche, and Willpower.

Select Skills. There are “Simple” and “Complex” skills, with different costs for both. Your attribute level in the closest related attribute to a particular skill imposes limits on the skill level. There are also specialization rules, which allow you to get a slight edge in a particular area of one of your skills.

Calculate Secondary Attributes. A lot of games which have a set of calculated secondary attributes start with a core of generalized attributes and then attempt to get more specific secondary attributes through various mathematical formulas and attribute combinations.

Well, in Silhouette the mathematic formulas are there and so are the attribute combinations – but the process has been inverted. As you probably noted above, the attributes in Silhouette are very specific (allowing you to specify a character with a very large body, but who is also in bad physical shape, for example) – the secondary attributes are more generalization compositions of these attributes (along with several combat-specific scores): Strength, Health, Stamina, Unarmed Damage, Armed Damage, Flesh Wounding Score, Deep Wounding Score, Instant Death Score, System Shock Score. This works a lot better, since it gives you both the specific control and the generalized usefulness of, for example, a Strength score.

COMBAT

Combat in the Silhouette engine is basically an extrapolation of basic action resolution (as it is in most games of the past twenty years).

Initiative is determined by rolling a Combat Sense opposed Skill test, in which the character with the highest score goes first, second highest second, and so forth. Tied results act simultaneously.

Two actions can be attempted during a combat round without any penalty – additional actions may be attempted, but each additional action adds a -1 penalty to all actions attempted in the round.

For combat actions the character makes a skill check against the pertinent skill, which is opposed with a Dodge skill check on the part of the defender. Modifiers cover typical combat situations (different attack ranges, speed of attacker and target, and so on) – these are all accessible through easy-to-reference tables (and can also be improvised by the GM fairly easily). There’s some specific rules for handling grenades and burst fire.

If a character is injured, damage is determined by multiplying the Weapon Damage Multipler and the Margin of Success on the opposed skill check together. This number is compared to the character’s Flesh Wound, Deep Wound, and Instant Death scores and the character takes a wound based on the highest score surpassed. If none of the scores are surpassed, the injury was so minor that it was inconsequential in game terms. (Example: A PC gets an MoS of 3 when shooting a bow at an NPC. A bow possesses a damage multiplier of 7, so the damage score is 21. The NPC’s Flesh Wound score is 16, and there Deep Wound score is 25. So they take a Flesh Wound (since 21 is higher than 16, but lower than 25).) Each wound applies a penalty to action checks (-1 for each Flesh Wound, -2 for each Deep Wound)

Death can occur in one of two ways: Either the play takes a massive amount of damage in one hit (which exceeds his Instant Death score) and dies immediately; or from trauma caused by multiple wounds. The latter takes place when the character’s action penalty from wounds exceeds their System Shock rating. Various healing rules exist which can save the character from “death” if they are reached soon after their penalties exceed the System Shock score.

Several additional rules exist covering non-standard combat options – drugs, stimulants, fire, poisons, radiation poisoning, and so forth. These work intuitively with a handful of simple charts.

In practice the combat system is simple, sleek, and dynamic. It’s as smooth as clockwork, producing a fast-paced brand of action which is also very realistic when it needs to be – the unique damaging mechanic, in particular, works surprisingly well. The one thing missing from this section of the book are some solid examples. Actually, examples would be helpful throughout the rules to help clear up the problems left by the muddy wording of some passages.

THE TACTICAL SYSTEM

I have found, from experience, that while a summary of the basic components of a roleplaying system can generally be useful, a similar summary of a tactical system is both impractical and seldom illuminating. My theory is that this is because both the strengths and weaknesses of a tactical system are in the details, and therefore I would have to relate to you most or all of the system in order to give you any meaningful perspective on it.

That being said, I do feel comfortable in highlighting some of the unique strengths of the Silhouette tactical system (particularly as it is applied in Jovian Chronicles). I would also highlight the weaknesses, but I haven’t really found any upon which to comment.

First off, for all the roleplayers quaking in their boots at the thought of moving miniatures or counters around a table, let me assure you that Dream Pod 9 has not forgotten you. They have provided a set of abstract vehicle rules which take up no more than a page and easily allow allow you to include vehicular combat without whipping out the hex paper.

As I noted before, a feature of the Silhouette game is the complete compatibility of the roleplaying and tactical rules. This is not a matter of conversion tables, it is a matter of both sets of rules being based upon the same engine. Because of this, it is as easy as pie to create a hybrid roleplaying-tactical campaign. The game includes a brief set of guidelines for the GM which includes extras such as hidden units, PC crew injuries, and so forth.

In turn, this should not be construed by tactical gamers as meaning that Jovian Chronicle’s tactical engine is “corrupted” by roleplaying elements. The tactical engine is fully capable of acting as a strong, stand-alone game in its own right. About the only unfortunate thing at the moment is the lack of Jovian Chronicles miniatures on the market at the moment, but that situation may be corrected in the near future.

There are basically three primary features which make Jovian Chronicles unique (several of which distinguish it from Heavy Gear’s tactical system as well):

First, Jovian Chronicles implements a unique vectored combat movement system which can be used in either two dimensions or three; with two, three, and even four vectors axes. The fourth vector is used for 3-D games using a hex map (so you get three 2-D axes running through the six sides of the hex, plus one vertical vector to add the third dimension). Once again, Dream Pod 9 has provided multiple levels of complexity and accuracy depending on your experience and personal tastes.

What is a vector system and why do you need it? In space, for those who slept through physics class, there’s no friction and little gravity to slow your ship down – so Newton’s law (“a mass in motion will tend to remain in motion”) will display its full effectiveness. On Earth, if I accelerate my car forward and then turn the car and accelerate in a new direction, the friction of the ground and the atmosphere means that my car will stop moving in that original direction (and that if I stop accelerating, my car will come to a stop). In space, however, if I did this I would keep my momentum from both accelerations (unless they were in opposite directions) and head off at an angle relative to them. In essence, unless you take an action to stop moving , you’ll keep moving. And this becomes a composite equation – in which your speed forward, backward, left, right, up, and down (although these are all relative terms in space) is maintained unless you accelerate in the opposite direction. In other words, the vector system is a way in which if accelerate three hexes forward this turn, then, unless you accelerate three hexes backward next turn, your spaceship will move forward three hexes next turn as well.

This can become a logistical nightmare, and does in many games – it is very hard for you to keep track of all of your ships carry-over movement, and thus it is difficult to get a clear tactical view of the situation. Dream Pod 9 solves this problem through the use of “altitude” and “destination” counters. The former are used only for three-dimensional games (in which your ship can rise above the table surface or sink below it), but the latter are used in all games. Essentially when you finish moving your ship for a turn you duplicate the exact same move and put a destination counter for the ship down in the hex the ship would end up if the move was actually repeated. (So if you moved forward three spaces, you would put down the destination counter three spaces ahead of the ship’s final location.) “So what?” you say. Well, at this point instead of moving your ship the way you would in a more standard tactical game, you manipulate the destination counter. So if you wanted to, for example, move to your right two hexes and decelerate one hex you would move the destination counter two hexes to the right and one hex back – then you would move the ship to the destination counter, and move the destination counter to its new position (two hexes to the right and one hex back).

With this system, vectored movement is handled without you ever having to wrap your end around four different numbers. If you don’t believe me, feel free to try it out a couple of times. If you don’t like it, feel free to use a pure vector system – noting down the ship’s momentum along each of the vector axes.

The second thing of note in Jovian Chronicles are the Lightning Strike combat rules. In a standard space tactical game it is assumed that the two sides attempt to slow and match one another’s relative velocity in order to actively engage one another in combat. However, there is also a good deal of tactical and strategic advantage (in some circumstances) to building up a massive difference in the velocity between the two fleets and performing a “lightning strike” – where the two sides zoom past each other at incredibly fast speeds, getting only one or two turns of effective combat (in game turns).

Finally, Jovian Chronicles, amazingly enough, does not satisfy itself with just have space combat rules. Rules for planetary ground combat and planetary air combat are also included, plus some guidelines for tactical games set inside colony cylinders.

As a result, Jovian Chronicles easily establishes itself not only as one of the best space combat tactical games, but also one of the most versatile science fiction combat engines available. Round all of this out with the excellent Silhouette engine’s description of vehicles and technology and you have a tactical game worthy not only in its own right, but for its rightful part in the complete Jovian Chronicles gaming experience.

GENERAL NOTES

Which leaves us with a just a few general notes regarding Jovian Chronicles.

The book begins with an eight page short story. I am skeptical of gaming fiction in general, and downright biased against the quality of fiction in an actual gaming manual – if I see it, I am going to think it bad until it has proven otherwise. Dream Pod 9, however, has developed an uncanny knack for it – when it is short (their Heavy Gear books have a short piece of fiction at the top of each chapter) it is evocative and useful; when it is long it is compelling and revealing. “Playing Games”, the piece found here, acts as an excellent introduction to the setting – not only piquing your interest, but giving you a very real feel for what the world of 2210 is like.

The fiction also serves as an oblique introduction to the mini-campaign in the back of the book, designed to give new GMs an easy place to start. The campaign deals with JSS Valiant, the inaugural vessel in a fleet of new Valiant-class ships in the Jovian fleet. You get a little bit of intrigue, a little bit of action, and a lot of interesting possibilities. My own regret is that the mini-campaign is presented in a disjointed, abbreviated form.

Included in the mini-campaign is an eight-page full-color section, which is very welcome because most of this book is very art poor – particularly in comparison with other Dream Pod 9 products. Besides the full-color section, this fact is also mitigated not only by the cunningly rich lay-out work done with the art which is there, but also gorgeous two-page spreads at the top of each chapter. These last do an excellent job of showcasing Ghislain Barbe’s phenomenal talent.

The book is rounded out, after the mini-campaign, with a chapter of “Gamemaster Resources”, focusing mainly on advice for creating your own campaign. Although brief, this chapter performs with excellence. One of the more interesting ideas they present is that of a “Pilot” scenario, in which the campaign is given a test flight, just like a television show. In addition guidelines are given for various “Reality Distortion Levels” (means by which the campaign can be varied anywhere from hard SF to anime space opera) – including script immunity (at various levels of effectiveness), existential angst (you have to read these rules), and, my favorite, the “WOO Factor” (which they claim stands for (W)eapons (O)ut of (O)rdinance, but which all fans of Hong Kong Action flicks will recognize as something else altogether). They also deal with villains and give a number of campaign hooks (complete with an overview of the necessary preliminary work). A short section, but packed.

One last thing which should be noted: Jovian Chronicles features an extensive technical reference, designed not only for the pleasure of gearheads, but also a general introduction to concepts such as Lagrange Points for the neophyte.

Before moving on, I need to comment on couple more weaknesses in Jovian Chronicles. First, the entire manual is laid out in a font which is approximately one size too small – it not only strains the eyes when you’re reading, it also makes it harder to find information quickly.

Second, material throughout the book is plagued with a certain vague opaqueness. One example of this which has already been mentioned is the strange occurrence of passages which seem to demand footnotes reading “here’s some information about the Odyssey, which won’t make any sense without knowing the details of what happened during the Odyssey, and you don’t”.

Another, and far more troubling, example, however, is the skill check mechanic. Like many game engines today, the Silhouette rules supply some “basic” information about the resolution mechanic before character creation (giving you some idea of the effect all these numbers you’re plugging in will have in the actual engine): First how to roll and read the dice (complete with fumble rules); then they discuss action tests in general (comparing the die roll to a threshold); then they discuss opposed actions; and finally they reveal that in a skill test the number of dice you roll is equal to your skill level; and finally that there are many zero-average ratings in the game which will act as modifiers to your die roll under certain circumstances (and that Attributes are among these). In other words, they don’t just give you the basic mechanic – they give you all the steps which go into making up the basic mechanic, which allows both them and you to easily vary the basic mechanic in a great number of ways.

Here’s where it gets screwy. They revisit these concepts in the “Character Action” chapter, which follows character creation, and explicitly lay out how action tests should run. At this point they describe a skill test, in full, as:

The roleplaying game, like the tactical game, relies on Skill tests to determine the outcome of most character actions. Unlike the tactical game, however, the number of possible actions and Skills required to perform them is virtually unlimited.

Here’s the catch, folks: At no point is it explicitly laid out that the skill test mechanic consists of a die roll with a number of dice equal to your skill level, modified by an attribute (I know for a fact this is the way it is supposed to be done based on other Silhouette systems).

This can be implied in various ways: For example, the passage about attributes acting as modifiers. Plus, each skill has an attribute associated with it. Unfortunately, both of those have other explanations – attributes are explicitly assigned as modifiers for attribute checks; and we’ve already discussed that in character creation the associated attribute acts as a limiter on a character’s maximum skill level.

This is a massive, gaping flaw in the presentation of the rules and should definitely have been caught by a playtester.

(Looking back at Heavy Gear I can see that both editions of that game have a passage regarding “any applicable modifiers” (which Jovian Chronicles lacks), which by context would seem to include attributes – although obliquely. Tribe 8, finally, added a specific passage covering this rather basic element of the game system.)

CONCLUSION

Jovian Chronicles has a rather fair share of faults and flaws in it. It is a testament to its immense strength, however, that despite these slight foibles it still comes across as a a product of major significance, power, and potential. The setting is evocative, deep, and useful in many, many ways. The rule system is simple, flexible, and versatile. The overall feel of the product is clean, professional, and impressive. Minor flaws in presentation cannot thwart any of that, or the conclusion that derives from it — Jovian Chronicles is one of the best games on the market today. Capable of appealing to fans of hard science fiction, anime, and space opera (plus anything in-between) this book definitely deserves a place on your shelf.

Style: 4

Substance: 5

Author: Phillippe Boulle, Jean Carrieres, Wunji Lau, Marc A. Vezina

Company/Publisher: Dream Pod 9

Cost: $29.95

Page Count: 232

ISBN: 0-895776-13-2

Originally Posted: 1999/08/24

It’s interesting coming to these Jovian Chronicles reviews at the current moment: I’m currently in the middle of a pretty serious Eclipse Phase binge and for some reason these two games strongly remind me of each other. I mean, there’s obviously radical differences between the transhuman horrors of the one and the mecha war stories of the other. But, nonetheless, the commonalities of the Solar diaspora, tin can habs, and the like create a sense of commonality and the excitement I feel in exploring Eclipse Phase reminds me a lot of the excitement I had when I was first exploring Jovian Chronicles.

Poor, benighted Jovian Chronicles. I still strongly recommend these core products; the setting really is wonderful and the early Silhouette mechanics are a joy. But if you’re looking for a case study on how to neglect, abuse, and mismanage a game there are few better candidates.

For several years after it was initially released, the game received essentially no support whatsoever. Then, when the support finally came, several disastrous decisions were made. (During this time I was working as a freelancer for the company.) Midway through the development cycle, the decision was made to cut the size of their supplements from 124 pages to 80 pages; this is despite the fact that some of these books had already been written and others were in the process of being written. Almost simultaneously the setting saw a major change in artistic direction, so that the titular good guys were suddenly rewritten as dystopic bad guys. And then the company decided to release a completely incompatible system called Lightning Strike that had supplements containing information which actually contradicted information found in the RPG setting supplements.

I bear some responsibility for this mess. I pitched DP9 a “security briefing” concept for the Jovian sourcebook: The setting material would be presented in the form of a Solapol briefing file with excerpts taken from other documents, intercepted communications, guidebooks, and the like. The structure would present useful, practical information for the GM in a format that would also allow it to be excerpted and used as handouts for the players. The line developers loved the idea and decided to revamp the entire sourcebook line to use the format. What I didn’t know at the time (and didn’t discover until much later), was that this included having a different freelancer rewrite an entire sourcebook that had already been finished in an effort to convert it to the new concept. (He may have also been simultaneously trying to cut 20-40 pages worth of material in order to squeeze it into the smaller book length. I was doing the same thing simultaneously while in the middle of writing my first draft.) Ironically, most of the material I wrote for the Jupiter sourcebook was then thrown out.

In any case, this was all years later: Copies of the first edition of Jovian Chronicles are relatively easy to track down and I heartily recommend that you do so. There’s a lot of awesome packed between those covers.

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.