Tagline: The best character sheets done for any game, ever. Period.

WHAT IS THIS?

This is a review of three associated products for Guardians of Order’s Sailor Moon Role-Playing Game (which I’ve reviewed elsewhere): The Knight Character Diary, the Dark Warrior Character Diary, and Sailor Scout Character Diary.

This is a review of three associated products for Guardians of Order’s Sailor Moon Role-Playing Game (which I’ve reviewed elsewhere): The Knight Character Diary, the Dark Warrior Character Diary, and Sailor Scout Character Diary.

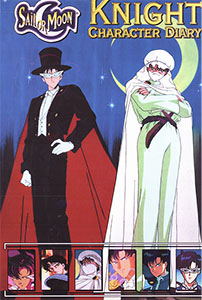

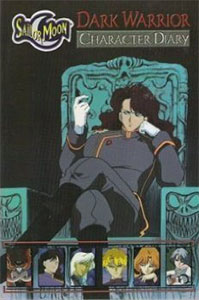

Essentially these are character sheets from a company that dreams really big (each 56 page pamphlet is for use with a single character). Each diary contains a 14-page character sheet, forty diary pages, a title page which you can personalize, and a dozen or so pictures (appropriate for each type of character) which you can use for your character portrait.

HOW GOOD IS IT?

Very, very good – surprisingly enough.

Personally, I don’t buy character sheets. The last time I bought a packet of character sheets was back in 6th grade, when I was an avid AD&D player and those of us in the group who could afford to splurge on store-bought character sheets (instead of writing it out on notebook paper) became possessed of a certain prestige.

In point of fact, I didn’t buy these – they came in the form of reviewer comp copies from GoO. But if I was playing in a Sailor Moon campaign I’d be sorely tempted to break my habit now that I’ve seen these.

For starters, the 14-page character sheet is absolutely wonderful. Often when you see extended character sheets like this all that’s really contained on them are lots of lines which are supposedly dedicated to “character history”. There are certain elements of that here (a page dedicated to it, but laid out rather nicely in segmented portions of your history – “Silver Millenium” and “Earth Childhood” in the Sailor Scout diary, for example), but by-and-large the extended sheet consists largely of closely targeted questions meant not only to spur your creativity, but also to facilitate ease of reference.

What this reminds me most of is another memory from my avid AD&D days (it’s nostalgia time). Back then I participated heavily on the FidoNet AD&D echo (like a Usenet newsgroup, but propagated at a much slower speed between individual BBS message boards). While there I happened to pick up something called the “Personal Code”, which was designed by a wonderful young woman named Alesia Chamness. It was a  replacement for AD&D’s alignment system which encouraged the individual player to develop his character through a series of targeted questions. It was useful for defining your character in writing, for spurring creativity, and for developing your existing ideas. Really great stuff, and highly reminiscent of what you’re getting in this diaries.

replacement for AD&D’s alignment system which encouraged the individual player to develop his character through a series of targeted questions. It was useful for defining your character in writing, for spurring creativity, and for developing your existing ideas. Really great stuff, and highly reminiscent of what you’re getting in this diaries.

The diary itself is done really nicely. The left-hand pages are plain white with a border which is evocative of the character type in question (a rose is in each corner of the border in the Knight Character Diary, for example). The facing pages, on the right side, takes advantage of the rich wealth of artwork which is available to GoO for this game line (in the form of animation stills) – the entire page is taken up by a grey-muted image (again, appropriate to the character type). Because they’re muted images you can easily write over these, and they end up providing a fantastic feel to the entire product. You’re not just buying a book of blank pages, you’re buying something that really ends up enhancing the recording of your character’s life and exploits.

Finally, the stock pictures at the end (which are designed to be xeroxed, cut out, colored, and pasted onto the title page which leads the book) are useful for the artistically-disinclined.

WHAT WOULD I CHANGE?

Not much. I’d probably drop the price down to $4.95, rather than $5.95. Crossing the $5 barrier to $6 makes these books seem just a little too pricey to me. On the other hand, I’m sure that GoO has priced these where they have because that’s where they can make a profit.

Not much. I’d probably drop the price down to $4.95, rather than $5.95. Crossing the $5 barrier to $6 makes these books seem just a little too pricey to me. On the other hand, I’m sure that GoO has priced these where they have because that’s where they can make a profit.

As for the actual content of the pieces, the only I’d change – or rather, expand – are the stock photos. I feel rather limited by the fact that the only picture they have are of the characters from the animated series itself. It’s really bad in the Knight Character Diary, because all you’re basically getting are a variety of pictures of Tuxedo Mask. Again, though, I don’t see any way for GoO to have done anything differently – they’re constrained by the artwork which is available to them.

IS IT WORTH IT?

If you’re the type who buys character sheets as a matter of course, then I would say definitely yes. The price may seem a little steep at first – but, trust me, you’re getting your money’s worth.

If you don’t typically buy character sheets, then there’s a goodly chance you aren’t going to break the habit with these. On the other hand, I’d suggest taking a peek at them next time you’re in the store. They just might surprise you.

Style: 5

Substance: 4

Author: Karen McLarney

Company/Publisher: Guardians of Order

Cost: $5.95

Page Count: 56

ISBN: n/a

Originally Posted: 2000/03/12

What I said about not buying character sheets was nothing but truth: When I first started roleplaying, I photocopied the sample sheet off the back of the BECMI basic manual (which produced the double-sided 8.5 x 11 character sheet 2-up on a single sheet) and got so used to using it that when I bought a pack of the official sheets they seemed weird to me. I don’t think I’ve ever actually paid for an official character sheet ever again.

Of course, in the digital era that doesn’t mean as much as it used to: Although I don’t buy them, I have used a variety of official sheets over the years. And a really great character sheet — like the Sailor Moon Character Diaries — really can transform a game. Most recently, the character sheets for Numenera and The Strange are like that: The former through sheer beauty and utility; the latter through the excessively clever method it uses for handling characters shifting between alternate realities.

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.

Government-Funded Robot Assassins from Hell – Mission One: Kill All Evil Game Designers (henceforth, for obvious reasons, referred to merely as Government-Funded Robot Assassins) is a card game dating back to 1995.

Government-Funded Robot Assassins from Hell – Mission One: Kill All Evil Game Designers (henceforth, for obvious reasons, referred to merely as Government-Funded Robot Assassins) is a card game dating back to 1995.