DINOPLEX CATACLYSM

It’s Jurassic Park, but on a space station!

This is a cool idea for an adventure, but this scenario is, unfortunately, sabotaged by lackluster execution.

For example, there’s a player handout designed as a kid’s activity game where they’re supposed to find all twelve dinosaurs in the Dinoplex! If they can find them all, they get a free sticker set! But there aren’t twelve types of dinosaurs in the adventure. Even if you include the wooly mammoths and sabretooths which, despite the adventure’s claims, are clearly not dinosaurs, there’s still only eleven creatures listed. I really want this to be something clever – are they supposed to count Tony the T-Rex, the park’s mascot, as a separate dino? is the task deliberately impossible so the park never needs to give the kiddies their sticker sets? – but I’m pretty sure it’s just a mistake.

The adventure primarily consists of six park zones, each given a brief description, a list of attractions, a list of “dinosaurs”, and a one sentence description of how everything is changed “post-disaster.” I can hazard a few guesses on how this material could be used to actually run the adventure – a sector crawl seems like a good fit? but the park map is a hexmap, so maybe per-hex random encounter checks? – but at a certain point I’m no longer really describing the published adventure.

Dinoplex Catalcysm also briefly flirts with the idea that the resort could be used as a shore leave location, possibly more than once, before the disaster strikes. Since taking shore leave is a central mechanic in Mothership, required for characters to recover and advance, this is a very clever idea that could really give the scenario some extra punch. Unfortunately, it’s not actually developed into something useable: First, it’s not integrated into the actual shore leave mechanics. Second, the pre-disaster amusement park activities are largely not interesting enough to support any meaningful spotlight during actual play.

The same problem is found in the meat of the scenario: The post-disaster details of the park are simply too shallow, in my opinion, to support meaningful play. The fundamental details of the park are also too sketchy, with, for example, tundra environments requiring specialized cold weather gear being located a couple hundred meters from humid swamps with no explanation beyond possibly a vague wave in the direction of a “weather system.” Even the “disaster” which triggers the adventure is a headscratcher. I actually missed it entirely during my first read-through of the adventure because it’s hidden away as a single sentence in a sub-bullet point.

Ultimately, this seems to be more the concept of an adventure than an actual adventure.

GRADE: D

YEAR OF THE RAT

The PCs are sent to retrieve the black box from a curiously nameless casino ship that went missing a month ago. Unbeknownst to the former owners or the insurance company looking to avoid a costly payout, the ship has become infested by a rat-like alien species.

The adventure primarily consists of a one-page map-and-key spread detailing the ship. This has some really nice details, although the ship consisting of only a single two-dimensional deck feels a little wonky.

An important note: Although at first glance this appears to be formatted as a trifold module with six panels of information, for some inexplicable it’s not actually designed to be folded into a pamphlet. So if you do, in fact, print the adventure, fold it up, and attempt to read it, you will be very confused.

This disorientation is not helped by a layout which is clearly more interested in looking “cool” – with lots of graphical artifacts, “dirt,” and the like — than being usable or even legible.

Also worth being aware that, since the PCs will be looting a casino ship, their payout from this job is quite likely to be incredibly large. (And that’s before factoring in the insurance company’s payment to the PCs being salvage rights for the entire ship… which doesn’t quite make sense to me. You might also want to interrogate the logic of “ship went missing, here are the coordinates where it’s located” before running this.)

Despite a few rough edges, though, Year of the Rat is a solid adventure that can be a lot of fun in play. The rat-like aliens are, of course, the stars, and they can be a wonderful change of pace in a long-running Mothership campaign: Creepy, varied, and interesting, but also an infestation that the PCs can actually triumph over and clear out.

GRADE: B

MITOSIS: ESCAPE FROM STAR STATION

At a cutting-edge research station, a bacterial and/or viral outbreak causes some humans to mutate into either Lethian Braniacs or Cyberviral Goons. These mutants seem to have formed gangs and divided the station between them. Oat milk inhibits the Braniacs, but causes the Goons to go berserk. Walnut oil has the opposite effect.

There’s a map that’s very difficult to read, with lots of symbols that are unexplained. There’s a random encounter table consisting of either goons, brainiacs, or goons AND brainiacs.

The key for Area 0 seems to suggest that the PCs are pirates who were captured and then locked up in the prison and then their pirate captain promised escape, but the escape never happened, and also the captain (who they might meet later) doesn’t seem to know who they are.

To be honest, there’s like five different things going on in Mitosis: Escape From Star Station, and none of them are properly explained. This includes the nature, reason, and timeline of the outbreak itself, with just a vague reference to the “Mitosis-bacteria breach” and the “Mitosis-bolstered cybervirus.” (But also “Mitosis” is a board game that was being played in the cafeteria?) The color version of the module is also essentially unintelligible, although thankfully a black-and-white version is included.

What little coherency I can piece out from the text seems more like a parody of Mothership than anything else. There is a zany, schlock horror that seems promising if the idea of playing through a movie that Mystery Science 3000 would mock is appealing to you.

But, particularly at $6, I really can’t recommend this one.

GRADE: F

SO YOU’VE BEEN CHUMP-DUMPED

This is an odd adventure because the title and pitch — while being quite evocative! — really have nothing to do with the actual adventure.

The pitch is:

A cheap Jump-1 ticket? You thought you got lucky.

Now, stuck in the airlock with the other marks, you couldn’t feel lower. Then the warning lights flash. You hear a loud clunk, and your stomach sinks. In a blink, you’re all gulped into the nothing beyond with a brief whoosh.

Stars spin as you tumble through space, screaming promises of violence upon the friend who said they knew the perfect guy, who turned you into a doomed chump. The sounds just rattle around inside your helmet. Your only hope is this vaccsuit you were lucky enough to save for, or inherit, or steal and paranoid enough to don before leaving solid ground.

I was really intrigued by this! A unique survival scenario with vibes similar to Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity? In addition to the proposed jump-travel scam, you could imagine whipping out this adventure in any number of situations: Things go wrong for the PCs when pirates board their ship! A catastrophic hull breach! The only way to kill the alien horror is by blowing the airlock!

How will the PCs survive?!

Unfortunately, it turns out that this isn’t the adventure So You’ve Been Chump-Dumped delivers. Instead, the answer to, “How will the PCs survive?” is, “They immediately bump into a covert science vessel where an alien experiment has recently escaped confinement.”

How convenient.

It turns out, though, that this other adventure is really quite good. The adventure key describing the ship is colorful and engaging. The alien organism is creative and dynamic, driven by procedural generators that will create a unique playing experience for every group.

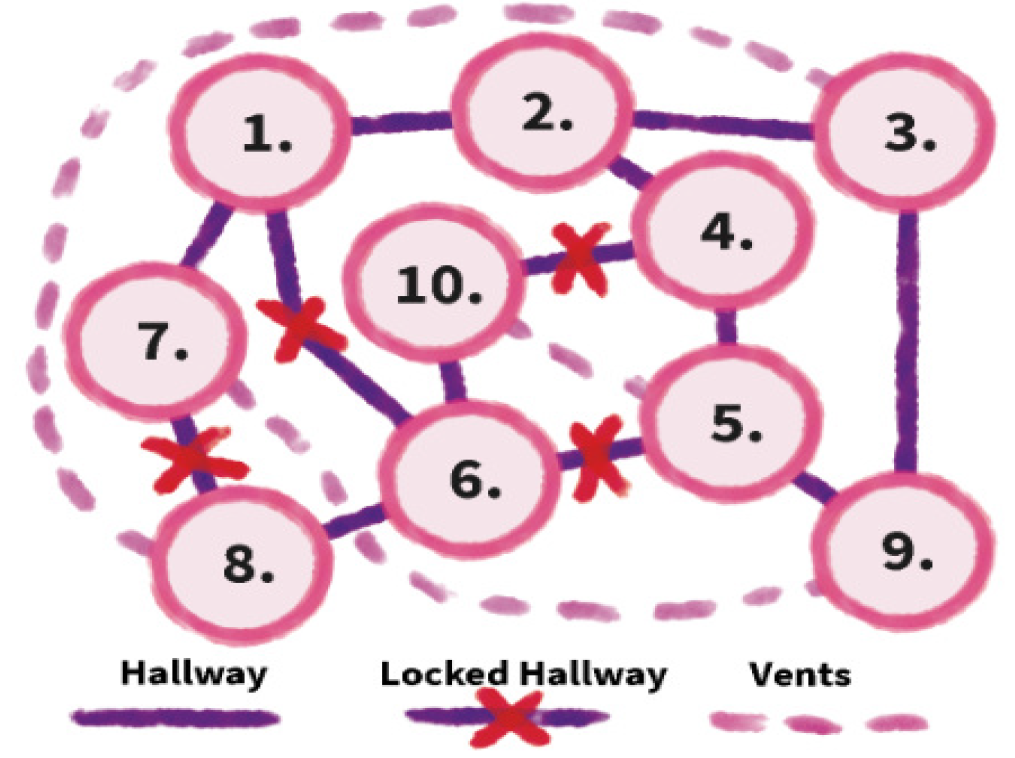

Other than the bait-and-switch, my only real quibble is the adventure map, which supposedly depicts the deckplans of the science vessel:

I’m obviously not opposed to a good pointmap, but this one is abstract to the point where it becomes impossible to actually describe the ship to my players. There are also some rather key questions raised by this map — like what, exactly, is the nature of these hallways? and what’s going on with this random vent system? — that I think you’ll want to straighten out before running this one.

I’ll definitely be drawing up a version of that map for myself soon, though, because So You’ve Been Chump-Dumped is definitely going into my open table rotation.

GRADE: B-