Session 19B: Beneath the Foundry

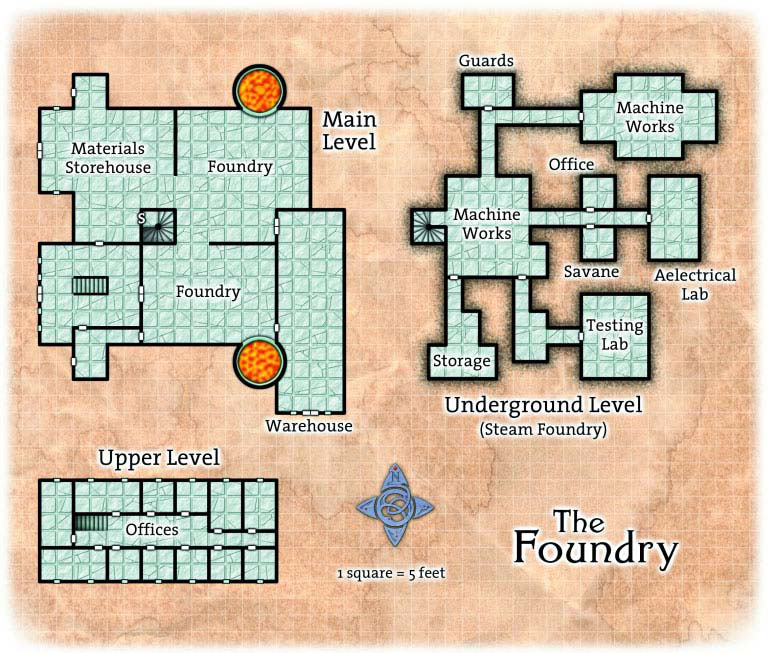

Tee missed all of this. Hearing the explosion she vaulted through the ventilation window and back onto the roof. Scampering twenty feet or so across the clay tiles and then looked through the ventilation windows about the first foundry. From this vantage point she could look down into the materials storehouse.

Although this week’s campaign journal is Session 19B, I’m actually going to continue chatting about the big, messy three-way confrontation between the PCs, the Shuul, and Shilukar that was wrapping up in the first part of Session 19.

This whole sequence worked really well at the table: The stakes were high. It was well-established that the PCs only had one shot at this. The battlefield was a complex, three-dimensional arena. The combination of action and stealth – which was being pursued in a mixture by both PCs and NPCs alike – gave the whole thing a very unusual texture and forced a lot of creative thinking (from both players and GM alike).

One of the essential elements that went into making this sequence work as well as it did is that I was blessed with a group of players willing (and able!) to seamlessly firewall player knowledge from character knowledge: When Tee split off from the group and got into trouble, the other PCs didn’t act as if they were gifted with clairvoyance and knew exactly what was going on. But they also didn’t fight so hard against the meta-knowledge that their characters turned into morons. Instead, they very smoothly took in what their characters knew and acted accordingly.

As the GM, I helped this process by specifying what information was flowing where: Something has just exploded in Room A, so characters X and Y hear the explosion; Y also sees the flash. And so forth. (These are really just crossovers, right? And they can be handled fairly seamlessly as brief “recap orientations” when you cut to the next group of PCs: “Okay, so you’ve just heard an explosion coming from the far side of the building. What are you doing?”)

By explicitly providing this information to the players, I’m removing the need for them to process it for themselves. They don’t have to think, “Okay, so the explosion just happened over there. Would I hear the yelling and then the explosion? Or just the explosion? Would I know where the explosion was? Or just a general direction?” All they need to do is focus on taking the information in as if they were their character and then making decisions based on the information they have.

THE GM’S FIREWALLS

The trick to doing this as a GM is to basically half-pretend that the other half of the party doesn’t exist when you cut between them. For example, let’s say that this wasn’t a situation with a split party: The PCs are exploring an area and, for whatever reason, an explosion goes off in the distance. What information would you give to the players in that situation? That’s the exact same information you should give to them even if the other half of the group were the ones causing the explosion.

This is kind of like a firewall in your own head, but rather than preventing meta-knowledge and character-knowledge from getting muddled up together, you’re preventing what Character A knows from getting muddled up with what Character B knows. You have to keep that clarity of perception clear in your own head so that you can present it clearly to the players, too.

Now, I say “half-pretend” because in actual practice the players DO know how you already described the scene of the rest of the group and you’ll use a sort of verbal shorthand to quickly review what they know without belaboring the details over and over again.

Which is one of the reasons why it’s great to have a group that can do this firewalling effectively. If I’d needed to take players into other rooms or pass notes or whatever, the pacing on this sequence would have suffered. Not only because of the logistical hassle of physically moving players around or writing out notes, but also because of the need to repeat information that otherwise would have only needed to be established once.

The GM also has to maintain firewalls between the NPCs. In fact, one of the quickest and easiest ways to make your NPCs feel like real people instead of puppets is for them to clearly demonstrate that their knowledge doesn’t map to the GM’s knowledge.

(An advanced technique you can use is to “cheat” this firewall in order to mimic NPCs with genius-level intellect that outstrips you own: In much the same way that it’s easy to solve a puzzle if you know the answer, so, too, can your NPC Sherlock Holmes make amazing “deductions” about the PCs because you already know the solution. But using this technique effectively is actually more difficult than it might seem, as it can easily lead to player frustration.)

This session also provides a great example of this kind of NPC firewalling, with both Shilukar and the Shuul being possessed of very different (and very incomplete) sets of facts.

You’ll also notice that, as the PCs figure this out, they’re able to take advantage of it in order to manipulate the NPCs.

OTHER FIREWALLS

Let’s back up for a moment: I said that passing notes and/or taking players into other rooms in order to have private conversations can have a negative impact on pacing. Does this mean I’m saying that you should never do this?

Not at all.

There is a cost to be paid for this stuff, but there are any number of circumstances in which the pay-off is worth it. The key principle, perhaps, is that you can’t put the genie back in the bottle: If you want to create an experience like surprise, paranoia, or mystery then it’s not enough to just ask someone to pretend that they don’t know a thing. They have to actually not know it.

Here are a few examples of where I’ve guarded information in order to prevent some or all of the players from gaining meta-knowledge.

- In the Ego Hunter one shot for Eclipse Phase, each PC is playing a forked version of the same character. Each fork has access to a unique subset of information and also a unique goal. I prepped custom handouts and took each player aside for private sessions. (The scenario is based around paranoia, secret agendas, and also the discovery of character and identity through incomplete information.)

- Similarly, in the Wilderness of Mirrors structure I designed for the Infinity RPG, each PC has a secret agenda. As the name suggests, the goal is to create paranoia and uncertainty in a universe filled with warring factions.

- In the Tomb of Horrors, when PCs choose to move through magical portals (that I know are one-way and, therefore, they cannot return through) my preferred method of resolution is to begin strict timekeeping and keep records of when the other characters pass through the portal. I can then jump to the other side of the portal and begin resolving actions as the PCs arrive one-by-one on the same schedule. (This heightens the extreme paranoia which is at the heart of the scenario.)

- In the Ptolus campaign, Tee’s decision to keep the Dreaming Arts and the other secrets of her elven clan secret from the rest of the PCs was the player’s choice. (Which is, at least 19 times out of 20, a good rule of thumb to follow: If a player requests a private meeting, honor the request. There’s some reason why they feel strongly about keeping this information secret, and you should generally default to respecting that.)