SUNBLIGHT

The biggest problem with Sunblight (and you’re going to be hearing me say this a lot) is that the lore just doesn’t hold together.

To start with, there are a couple weird conspiracies in the fortress.

The first is that Xardorok thinks he’s worshiping and following the commands of Deep Duerra (a duergar goddess), but in reality Asmodeus has punked him and is only pretending to be Deep Duerra!

This doesn’t really make a lot of sense and doesn’t really go anywhere. Further research suggests that 4th Edition killed Deep Duerra, but Sword Coast Adventurers Guide for 5th Edition just listed her as an active god again. So maybe this was an attempt to clean that continuity up (Duerra is dead, but Asmodeus has been impersonating her)? But mostly my take-away is that Wizards of the Coast really, really, really, really, really, really likes Asmodeus and needs him to be in every single adventure.

In any case, the conspiracy goes hilariously dumb when we get to this bit:

Infernal Tablets. The barbed devil [pretending to be a priest of Deep Duerra] spends its time chiseling on granite tablets to inscribe them with Infernal runes. Characters who can read Infernal script can learn about the devil’s manifesto, in which Klondorn reveals that Asmodeus, in the guise of Deep Duerra, is using the duergar to further his interests.

There are ninety-two granite tablets stacked about his room. Each tablet weighs 50 pounds and is 1 foot wide, ½ feet long, and 2 ½ inches thick.

“I have infiltrated Xardorok’s fortress. As an infernal spy, I will spend my days carving large stone tablets that say I AM A SPY and stacking them in large, clearly visible piles.”

The other conspiracy involves Grandolpha, a rival duergar despot that Xardorok wants to seduce and marry.

She’s not interested. But rather than marrying Xardorok, slitting his throat, and taking over the joint, Grandolpha has concocted a scheme where she suborns the guards one by one, then slits his throat, and takes over the joint.

Eh. Maybe she just enjoys suborning people.

But where I’m really left scratching my head is that Grandolpha orders her guards to unlock the doors of the fortress and let the PCs in.

The “plan” seems to be a vague hope that the PCs will politely kill Xardorok, but leave Grandolpha and her conspirators alone. But Grandolpha has no way of knowing that the PCs are coming. So is it just a standing order to the guard on the front door? “If anybody shows up, let them in on the off-chance they’re here to kill Xardorok! Boy, that sure would be great!”

This central silliness aside, Sunblight is a well-designed set piece. It has a good map with a lot of strategic interest and a good key with a lot of exploratory rewards. It would probably benefit from an adversary roster, but it would be relatively easy to throw one together.

AURIL’S ABODE

This chapter leaves me scratching my head.

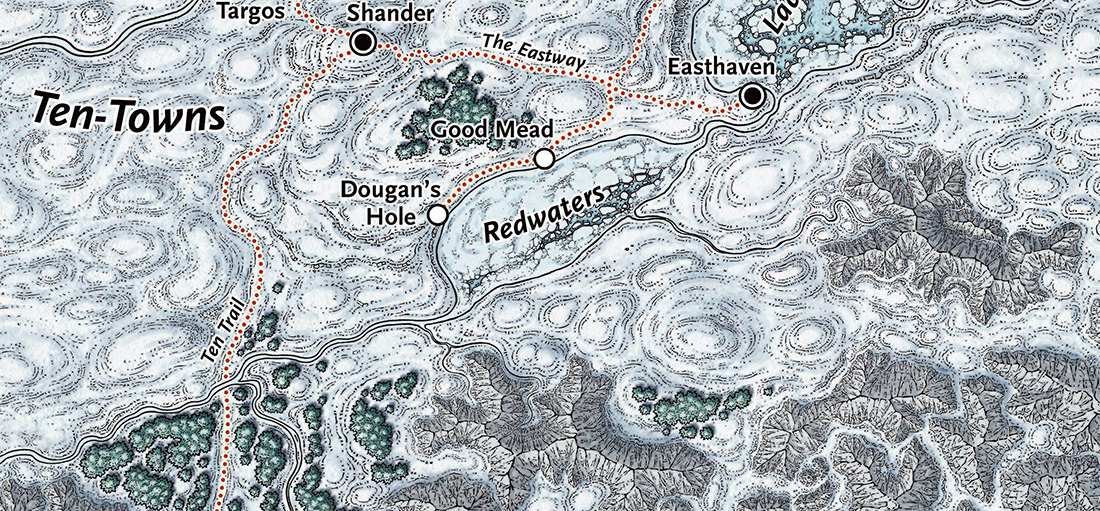

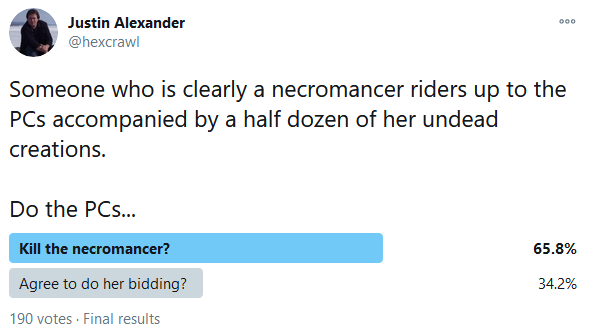

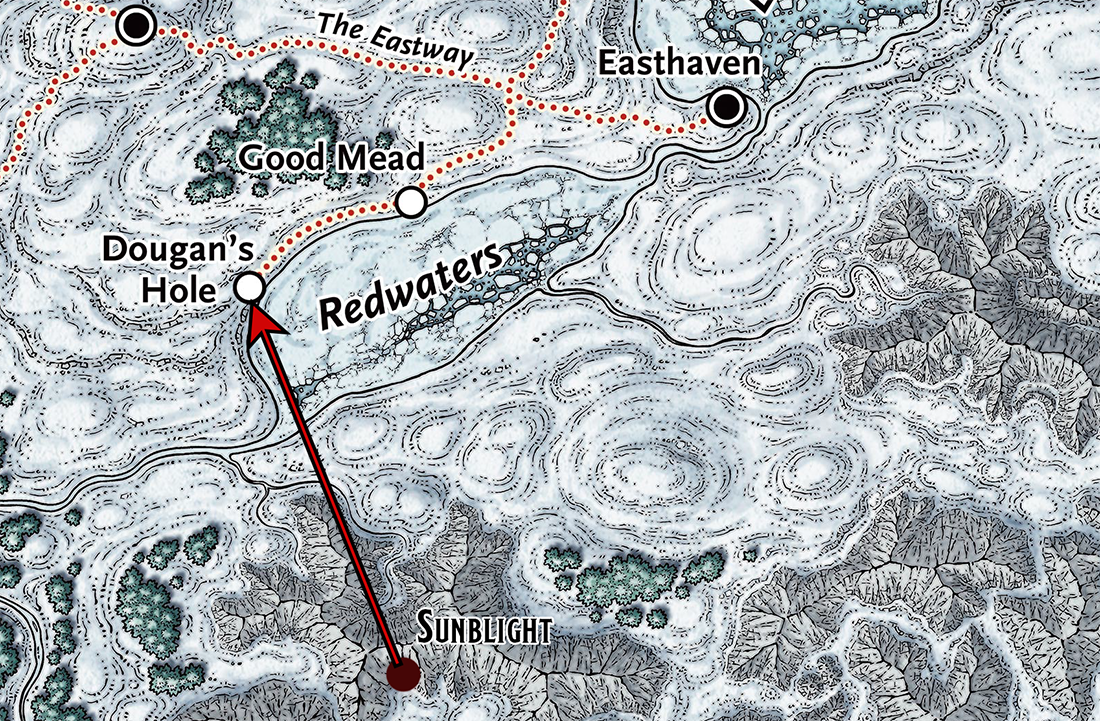

It starts off by saying that the characters “might come to this island on their own, hoping to put an end to Icewind Dale’s everlasting winter.” But there’s no meaningful mechanism for that: Other than one random rumor, the only way for the PCs to discover where Auril lives is for Vellynne the Necromancer Ex Machina to tell them.

When I first heard that Auril was going to have three different forms (which was a major element in the pre-release publicity for the campaign), I girded my loins for an epic confrontation of mythological proportions: You can’t defeat a goddess just once! You’ll have to face her three separate times!

But… no. She’s just a video game boss shouting:

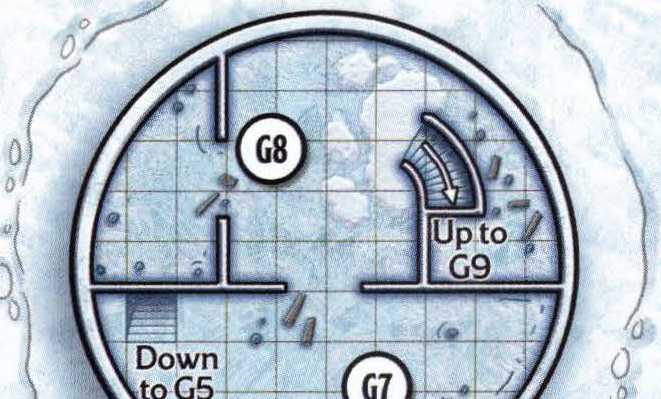

Even the setting of the fight isn’t inspiring. It’s Area G8 below, which is a frost giant’s ruined bedroom:

The way it’s scripted is that the PCs walk into the bedroom and Auril “staggers” out of the side chamber. FIGHT!

It’s a strategically boring space lacking in all gravitas.

(If the PCs don’t defeat Auril here, there’s a kind of half-assed bit later where she shows up at the end of the adventure and is like, “HOW DARE YOU SKIP MY FIGHT SCENE? RAWR!”)

The PCs don’t need to defeat Auril to end her winter curse on Icewind Dale, though: If they kill her roc (which is roosting on the roof), she can no longer fly into the sky to perform the ritual each night and the curse ends.

But… uh… Auril can fly.

And it’s D&D, so there’s like a zajillion work-arounds.

Meanwhile, killing her to end the curse doesn’t really make a lot of sense, either: The book is quite clear that if the PCs kill her, she’ll just re-manifest at the next Winter’s Solstice, restored to her full power. We’re later told that she’ll just decide to give up on the whole plan – so no worries! – but there’s no meaningful reason given for her making that decision.

Okay, but what about what brought the PCs to the island in the first place?

First: They’re looking for Nass Lantomir. They will, as far as I can tell, never find her.

The ship Nass took to the island sunk. She swam to the island and then died of frostbite (despite having multiple spells that would have prevented that from happening). The PCs:

- Have no way of knowing she came to the island.

- Have no reason to search the island.

They will, therefore, never find her corpse, which is in the middle of nowhere and mostly buried in snow.

… it’s a pity she’s carrying a magic item that’s fairly integral (albeit not strictly necessary) to the rest of the adventure.

The second reason the PCs have come to the island is to retrieve the Codicil of White, which is a religious primer for Auril’s worshipers. This mostly calls attention to the fact that the worship of Auril is a big ??? in the book and doesn’t make a lot of sense. But, regardless, the Codicil is locked in Auril’s basement and the security system is…

… well.

It’s triply dumb.

Dumb #1: The authors really want you to play through the security system, so we get some amateur hour railroading.

The door is otherwise unopenable, indestructible, and impassable. Any spell cast with the intent of bypassing the door fails and is wasted.

Cool story, bro.

Dumb #2: “This is a very important vault! Only authorized people should be let in! What’s our security system?”

“Only people who pass four tests can enter.”

Uh huh. Where are the tests located?

“Right outside the door of the vault.”

… uh huh.

Dumb #3: These fucking tests.

Here’s how they work: The PCs walk through a magic door and are teleported to a Raghed tribe which is very conveniently facing a crisis perfectly themed to the test (Cruelty, Endurance, Isolation, Preservation) at the very moment that the PCs arrive.

This is not an illusion or fake-out. The book is VERY INSISTENT that this is REALLY HAPPENING.

So, like, the Preservation test has them arrive in a Raghed camp where everyone has been killed except a nine-year-old kid. The PCs have to save him.

Wow.

Lucky thing that literally happened JUST as the PCs opened the magic door, right?

It gets dumber, though, because the PCs explicitly don’t have to all take the test at the same time. So after the first group goes through the test… what happens when the second group opens the same door?

In multiple places the adventure talks about the logistics of taking tests at different times on the VAULT side of the door, but never once explains what the second or third or fourth pass on a given test will look like for the characters actually taking it.

By the way, if you don’t get the Codicil out of the vault, the entire campaign breaks and you can’t play any more. So if the PCs fail the tests, some NPCs stop by and let them in.

…

All in all, Auril’s Abode is the only part of the adventure that I think is actually straight up crap. (Except for the art, which continues to be fabulous.)

This is a pity because this is THE adventure promised by the cover and title of the book.

When I got to this chapter I was literally rubbing my hands together with glee. HERE WE GO!

And then… Meh.

THE LOST CITY OF YTHRYN

Eighteen hundred years ago, Ythryn was a flying city and part of the Netherese Empire. A strange artifact caused the city’s mythallar to malfunction and it crashed into the Great Glacier. It has remained completely sealed off from the outside world ever since.

On that note, I’ve noticed a weird design tic in WotC adventures: Ancient ruins that have supposedly remained undiscovered and unknown for centuries, but which the PCs nevertheless reach by journeying through cosmopolitan caves filled to the brim with people.

Brief segue while we’re in these caves. This room is one of the funniest things I have ever read in a D&D adventure:

H21. FROZEN FROST GIANT

Entombed in the icy floor of this twenty-foot-high cave is the frozen, well-preserved corpse of a frost giant. Scratch marks in the ice suggest a half-hearted attempt to excavate the remains.

Really fantastic imagery here! Frozen ice cave. The creepy giant corpse. It’s super atmospheric. Memorable. Very cool. (Pun intended.) And enigmatic! How did he get here?

A city fell on him.

…

Not making this up. He was crushed to death when the flying city fell on top of him.

And, as we all know, when a city(!) falls on top of you, what happens is that your perfectly preserved corpse ends up flawlessly preserved in ice.

The best part is that if you look at the map, the city actually ended up directly BELOW him. So the city fell on him, crushed him to death (without mangling his body in any way), and then… phased through him to its final resting place?

In any case, the PCs eventually make their way through the caves and end up in the buried city of Ythryn. The book is a little vague on this, but the intention seems to be for the PCs to enter a huge cavern and be able to look down at the ruined city below them.

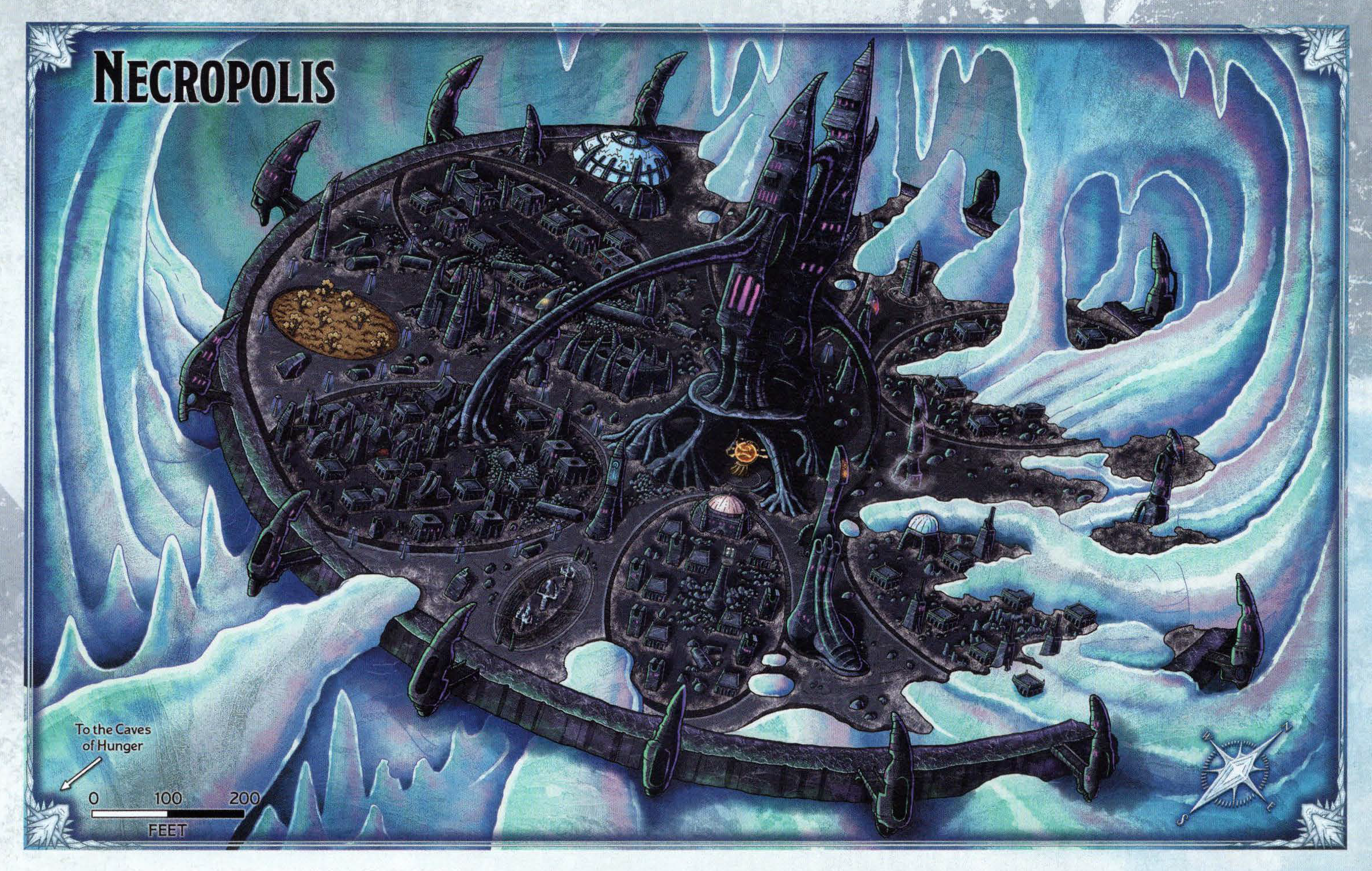

At which point you show them the Players’ Map of the whole thing:

Then they can explore the city by basically just pointing at cool stuff and saying, “Let’s go check that out!”

This isn’t the only way to run a ruined city scenario, but it’s a pretty great way to do it.

I do have a couple of quibbles here.

First, the scale of the city is such that you can walk across the whole thing in ten minutes, which seems to sap some of the epic scope. To be fair, this in itself is an attempt to compromise with the harsh realities of the 5th edition core rules: Slow travel pace is 200 feet per minute in the core rules; here the writers invent a “cautious rate” of 200 feet every 5 minutes. On the other hand, the scale also doesn’t seem to sync up well with the individual building maps, so you could probably double the size of the city to no ill effect.

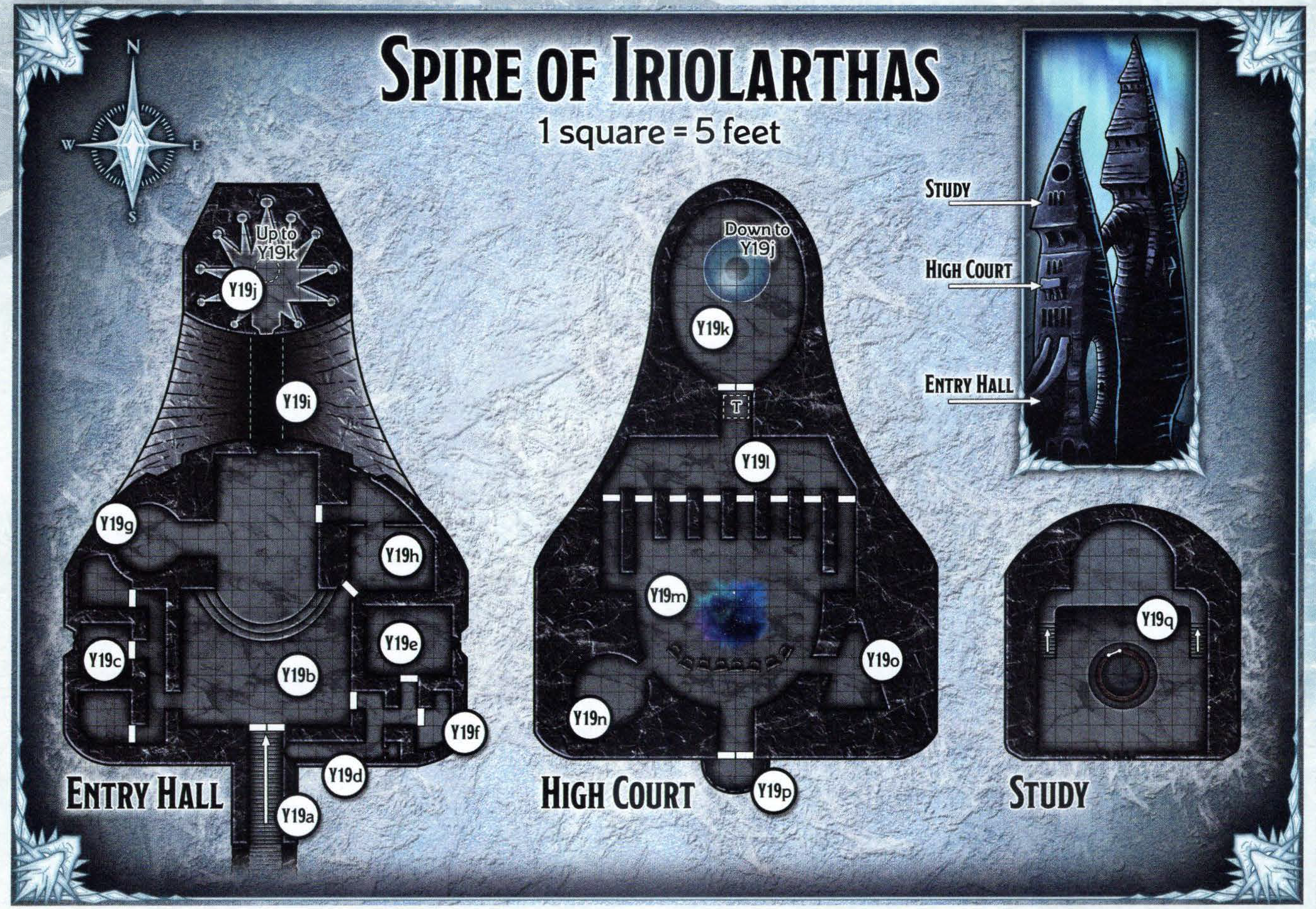

Second, one of my personal pet peeves is when building floorplans don’t match the picture of the building. But this becomes particularly egregious when the intended interaction of the game is literally “point at picture, then go to that place.” For example, the Spire of Iriolarthas:

The inset on this map actually hides the full extent of the problem here. If you look at the Players’ Map above, you can see that this is just the tippy-top of the central structure in the city. Where the heck is the rest of the building?!

But even just looking at the inset is rife with problems: Where are the missing floors that are clearly depicted between the three floors shown on the map? And did you notice the strut clearly connected to the High Court that leads to the other half of the spire?

THE END OF THE CAMPAIGN

In any case, here in Ythryn we have reached the end of the campaign… and it all just falls apart.

There are three options given in the book for how Rime of the Frostmaiden can end.

ENDING OPTION #1: Activate the Reset Obelisk (a powerful artifact in the city) and save Ythryn.

Here’s how that works:

- The PCs take Iriolarthus’ staff of power.

- The PCs use it to activate the Obelisk.

Why is this a problem?

Well, Iriolarthas is actually a Netherse wizard who has spent 1,800+ years trying to solve this problem. Despite his “best efforts” he’s been unable to do so, despite having trivial access to everything he needs. (The staff is literally sitting in his office.)

Now, Iriolarthas is currently a demi-lich and that would probably prevent him from doing this himself. But there are other people in the city who would gladly help (and do). Also, he didn’t become a demi-lich for a long, long time. (Which is why there was time for his “best efforts.”)

Also: He’s only a demi-lich because his phyalactery was buried in the ice when the city crashed, so he wasn’t able to physically access it to feed souls into it. (This is not how phylacteries work. As the Monster Manual says, “The phylactery must be on the same plane as the lich for the [soul-feeding] spell to work.”)

But the BIG problem is that:

- The city is stuck because X needs to be done.

- X could have been done at any time.

And it doesn’t make any sense. Nor is it made to make sense for the players.

Maybe the players don’t realize it and it’s fine. But I still think it’s a problem.

And the solution would be easy: The fix to the Obelisk just needs to be an out-of-context element. This would force the PCs to leave the city, get the thing they need (and which the people trapped in the city lacked), and then come back.

This would also help explain some of the timeline issues the finale struggles with, which brings us to…

ENDING OPTION #2: Use the Ythryn mythallar to cast control weather and end Auril’s winter!

The problem here is that this doesn’t actually work:

You can use the Ythryn mythallar to cast the control weather spell without requiring any components and without the need for you to be outdoors. This casting of the spell has a 50-mile radius. For the duration of the spell’s casting time, you must be within 30 feet of the Ythryn mythallar or the spell fails.

This is actually the second time the book has asserted that a magic item that casts control weather will solve the problem. But it doesn’t really hold up, because the spell only lasts for 8 hours and requires the user’s concentration. So unless the PCs want to spend the rest of their lives in Ythryn perpetually casting the spell three times a day, it won’t help.

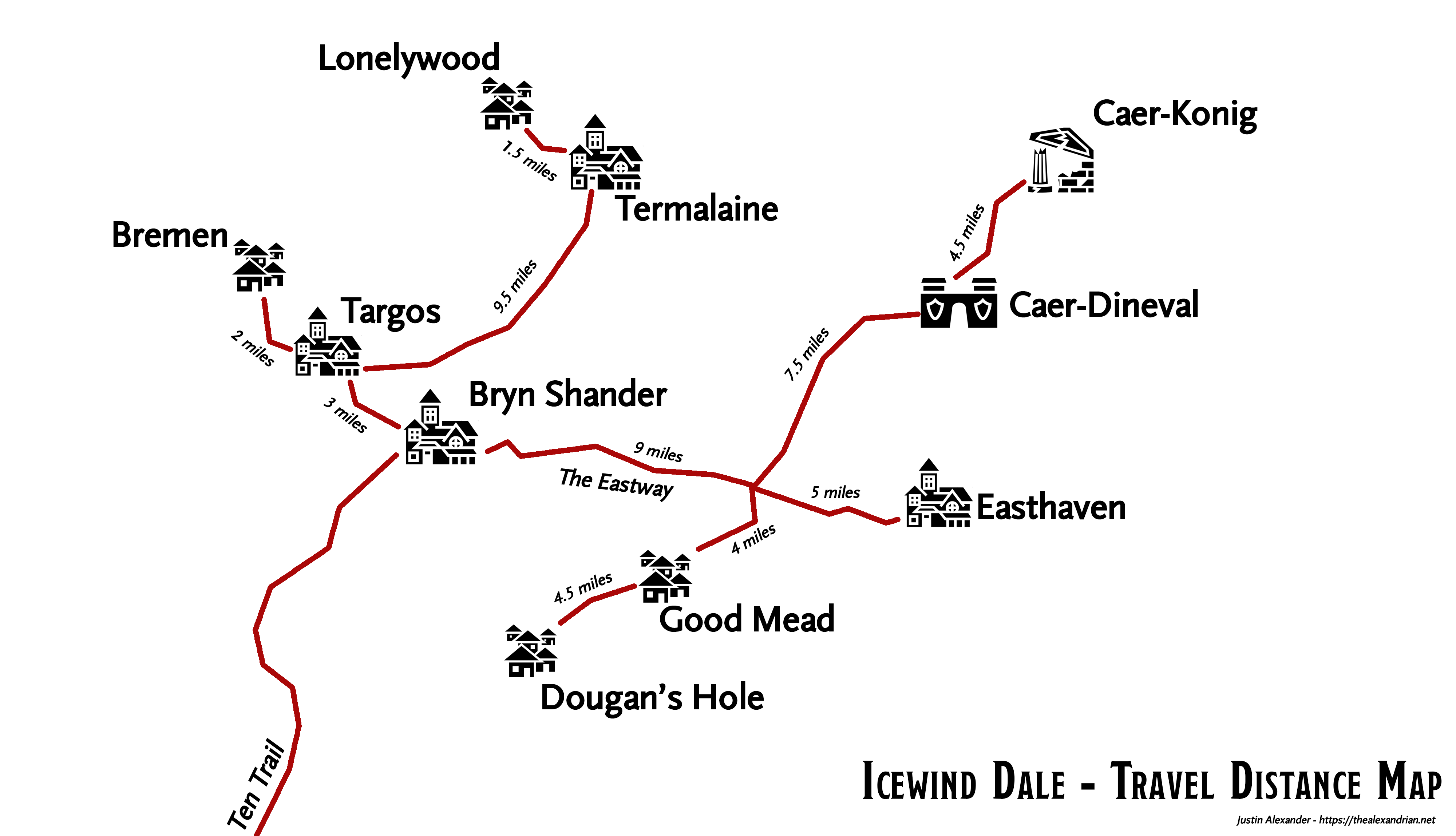

Also, the 50 mile radius of the spell isn’t far enough to reach all of Ten-Towns.

On the other hand, it’s nice to have an alternative resolution to the Auril’s Winter plot than just killing Auril…

…except not really, because the adventure says that using the mythallar immediately causes Auril to show up and fight them to the death.

So it’s all pointless.

ENDING OPTION #3: Twenty-four hours after the PCs enter Ythryn, Auril shows up with a loudspeaker and says, “YOU HAVE TAKEN TOO LONG! LET’S FIGHT!”

And then she fights to the death. Or whatever.

Mostly I don’t understand the design decision behind the timeline here:

- The PCs reach Ythryn.

- 12 hours later, competing archaeological teams arrive in the city.

- 12 hours after that, Auril shows up, summarily executes the competing archaeological teams, and triggers the endgame.

This seems like an interesting, dynamic situation for the PCs to interact with. (Think about the cat-and-mouse game between Indiana Jones and Belloq in Raiders of the Lost Ark.) But it seems as if the timeline has been set up just to punish PCs who take long rests in the city by giving the “bad ending.”

The other problem here is that Auril’s appearance feels arbitrary. You could trigger this, “THE TIME HAS COME FOR THE END OF THIS CAMPAIGN!” encounter at literally any point in the campaign and it would make as much sense as it does here. It doesn’t really proceed from everything the PCs have been doing, so it doesn’t feel like a culmination or a conclusion. It doesn’t resolve the story, because the PCs’ story hasn’t been about Auril.

You might also note that both Ending Option #2 and Ending Option #3 become null and void if the PCs killed Auril back at Auril’s Abode. This is a problem that often blights adventures in which a pseudo-sandbox gets welded onto the side of a railroad: The author (or GM) basically says, “Look at how much freedom you have! You even have the freedom to screw up the plot I’ve prepared!”

But then, if the players do that, the story doesn’t actually move in a new direction, it just continues shambling through the now empty and meaningless scaffolding of the prepared plot.

THE MISCELLANEOUS MISSES

Now that we’ve reached the end, let’s talk about a handful of other problems I had with the book — the smaller details that haven’t really fit into the discussion so far.

For example, three hundred page adventures need indexes. And if you don’t have an index, you’d better make really, really, really sure that the table of contents doesn’t have errors in it.

On a similar note, there’s a lot of basic continuity errors in the book. In one of the most egregious examples, a key piece of information the players need to finish the campaign is given in two contradictory forms on the same page.

REPUTATION SYSTEM: Given the nature of the Icewind Dale sandbox, the designers clearly realized that it would be really cool to have a reputation system. For example, they write:

Once the characters reach 4th level, they no long [sic] gain levels by completing the quests in this chapter. Even so, completing more than the required number of quests can improve their standing in Ten-Towns (see “Reputation in Ten-Towns” below)…

Unfortunately, two paragraphs later they say, “Eh. Fuck it.”

The adventuring party’s reputation in Ten-Towns improves as the characters gain levels, with the following results:

When the characters reach 3rd level, they [list of stuff].

When the characters reach 4th level, they [list of stuff].

So you keep gaining reputation even when you’re not gaining levels, but the only way reputation is tracked is by what level you are?

C’mon, man.

Furthermore, the only function of “reputation” is to unlock the Chapter 2 rumor table.

So why not just… do that? As written, it would be best to just drop the reputation “system” entirely.

Which is unfortunate, because a solid reputation system could really heighten the story of Icewind Dale and make it viscerally meaningful: The players would really be able to feel themselves becoming heroes of the Dale, and those mechanics would feed back into the narrative of rising up, overthrowing the Frostmaiden, and leading Icewind Dale out of her horrible winter.

IGNORE THE RULES! There are a lot of places in Icewind Dale where the book says, “The rules say this doesn’t work, so the rules don’t apply.”

For example, the chardalyn dragon is allowed to ignore environmental effects so that it doesn’t fall out of the sky. In another place, the authors want to have a very specific haunted house story, so they just arbitrarily declare that the ghost can’t be turned.

This is often just gratuitous. For example, the dragon would fall out of the sky because it doesn’t have a hover speed. But it’s a completely artificial dragon… why not just give it a hover speed? (Given that it’s kind of a steampunk creation made from evil crystals, I argue that giving it VTOL steam jets would just make it more badass.)

You probably won’t be surprised to discover that I’m not a big fan of this. It’s just not that hard to design stuff that works right with the rules.

BREAKING THE FOURTH WALL: I’ve mentioned this briefly above, but there are actually multiple points in the book where an NPC basically says, “Thou art not yet experienced enough! Return when thou hast attained a higher level!”

It’s kind of gauche. Frankly, I find this sort of, “You need to gain 500 XP before you can access this content!” stuff pretty off-putting even in a video game. In a tabletop RPG? It’s completely unacceptable.

BOXED TEXT: Quite a bit of boxed text in Rime of the Frostmaiden is very bad. Take this example from the caves around Yrkyth:

Frost-covered blocks of stone jut from the floor of this ten-foot-high cave of ice. Perched atop the largest stone is an emaciated kobold with glowing red eyes. It bares elongated fangs as it hisses at you, then scampers away.

First, there are too many places where the action (or inaction) of the PCs are assumed. That’s a big no-no.

But the really odd thing I found here was how often the boxed text wasn’t actually describing the thing it was purportedly describing.

It was here in the caves that I finally figured out why, because the boxed text in the caves is constantly telling you the height of the ceiling but absolutely nothing else about the shape or dimensions of the area.

…

Did you figure it out?

The adventure is written exclusively for GMs using virtual tabletops. The assumption is that the GM won’t bother describing the room because the players can just see the map displayed on their computer screens.

Here’s a more egregious example from earlier in the book:

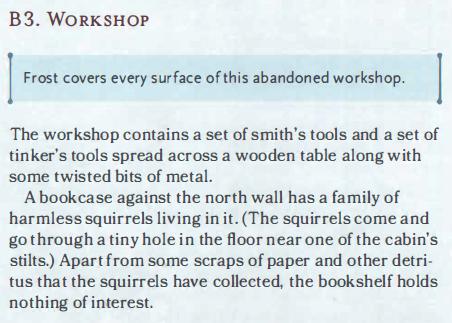

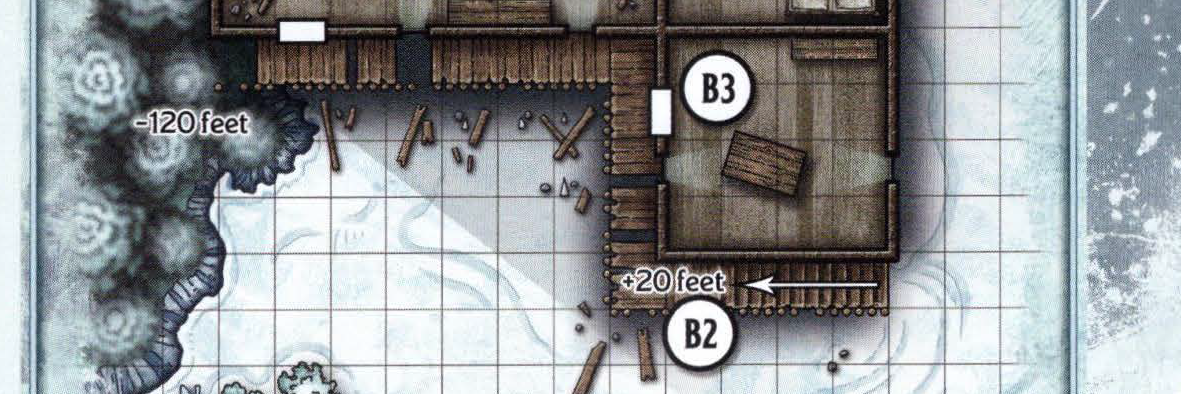

The room is clearly designed for the PCs to investigate the tool-covered table and the bookcase, but the description of the room doesn’t mention that they exist. And, yes, the answer is that you can see the table and the bookcase on the map.

THE STANDOUT MOMENTS

Remember at the beginning of all this that I said I liked the book quite a bit? But I’ve been analyzing its shortcomings for a few thousand words now, and that can leave a somewhat lop-sided impression. So I’d like to close things out by calling out some of the really nice stuff that the book does.

For example, the book introduces domesticated axe beaks which are used as mounts and pack beasts in Icewind Dale. And they’re awesome:

CUSTOMIZED CHARACTER CREATION: Icewind Dale also does a fantastic job of customizing character creation:

- It personalizes the scenario hooks by tying them to specific Backgrounds.

- It includes customized starting equipment appropriate for the setting.

- It includes a new option for a PC race in the Goliaths. (Even if no one picks the option, its availability still sets a tone.)

- It has a cool set of Character Secrets, most of which are tangibly tied to various elements of the sandbox.

There are all fairly minor things, but that’s kind of what makes them great. It really shows how just a few light touches can make character creation feel unique and special; investing the players in the feel and color of the campaign before play ever begins.

Playtest Tip: I’ve found that the Character Secrets tend to be the definitional aspect of character concept/background. So if you’re using them, you’ll probably want to deal them out up front so that people can build their characters around their secret. You can ameliorate this to some extent by dealing two or three secrets to each player and letting them choose.

WEATHER CONDITIONS: The designers use extreme weather conditions (particularly blizzards) to attempt to reintroduce some of the difficulties (or, more accurately, the interesting complications) of overland travel that 5th Edition’s core design generally stripped out of the game.

Icewind Dale isn’t really exploration-based, so getting lost in a blizzard, for example, doesn’t contribute to the navigational puzzle which would be found in such games. But it DOES create a dramatic tone: it brings Auril’s curse into the narrative at a fundamental level.

NON-COMBAT SUPPORT: Icewind Dale also does a great job of supporting non-combat resolutions and goals.

In Caer-Dineval, for example, the Knights of the Black Sword push hard for an alliance with the PCs, in a way that feels like it could reasonably happen (at least for awhile).

The Caer-Konig quest that takes you to a duergar outpost is primarily framed around “get our stolen stuff back,” which is a sharp contrast to the usual “clear the dungeon” goal found in a lot of published modules. (This pairs well with the xandered entrance to the outpost, which allows the PCs to either assault the main door or attempt to breach the complex through a bunker.)

The book also generally provides this support while avoiding contingency planning (which is the other typical pit trap scenarios can fall into with this).

For similar reasons, I like the Good Mead quest in which the PCs clear the dungeon… but then, after they’ve done so, a different bad guy shows up while they’re still there, likely inverting their relationship with the dungeon (so that they need to defend what they just invaded).

GREAT GRAPHICAL DESIGN: It’s unsurprising to discover that Icewind Dale: Rime of the Frostmaiden continues Wizards of the Coast’s fantastic graphical design (samples of which you’ve seen throughout this review.)

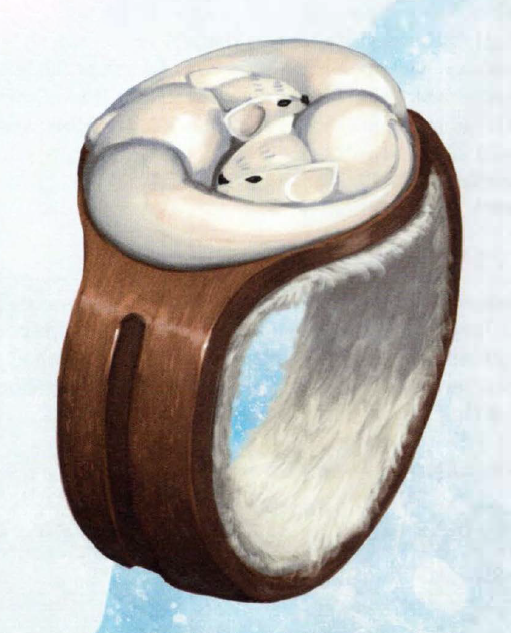

I’ve already mentioned the fantastic art illustrating even the weaker parts of the adventure, like Auril’s Abode. But this also extends to even the smallest details. For example, I simply adore this magic ring:

I want to own one in real life.

The advantages of Wizard’s graphical design extend beyond the book itself. For example, consider the stunningly beautiful (and incredibly massive!) chardalyn dragon miniature from Wizkids:

These rich graphical resources and other enhancements are a huge value add to your campaign that can be difficult or impossible to replicate otherwise.

These strong graphics are frequently paired to some fantastically flavorful material.

For example, I love the random encounter with Arveiaturace the White Wyrm: “…the dragon is buried under heavy snow. Her [dead rider who she once served and is still strapped to her back] is visible above the surface, looking like a frozen corpse in the snow. If the characters are close enough to touch the corpse, they’re already standing on the dragon’s back.”

That’s so unique, cool, and totally terrifying.

Gotta love it. Can’t wait to run it.

Style: 5

Substance: 3

Story Creator & Lead Writer: Christopher Perkins

Writing Team: Stacey Allan, Bill Benham, H.H. Carlan, Celese Conowitch, Dan Dillon, Will Doyle, Mikayla Ebel, Anne Gregersen, Chad Quandt, Morrigan Robbins, Ashley Warren

Rules Development: Jeremy Crawford, Dan Dillon, Ben Petrisor, Taymoor Rehman

World Building: John Francis Daley, Crystal Frasier, Jonathan Goldstein, Ed Greenwood, Amanda Hamon, Adam Lee, Ari Levitch, Mike Mearls, Christopher Perkins, Jessica Price, R.A. Salvatore, Kate Welch, Shawn Wood

Publisher: Wizards of the Coast

Cost: $49.95

Page Count: 320