As the PCs become embroiled in the Grand Game, Jarlaxle does not control an Eye. Nevertheless the Sea Maidens Faire and his ships are likely to become a target for a heist before the campaign is done:

- As noted in Part 1 and Part 5, Jarlaxle sold the nimblewright which murdered Dalakhar and can identify the purchasers. PCs may break into the ships in order to steal his shipping records or to access the crystal ball connected to the nimblewrights.

- The Bregan D’Aerthe team at Gralhund Villa (Part 2) successfully take possession of the Stone of Golorr.

- Jarlaxle’s agents may come into possession of an Eye at a later date, either by stealing it from the PCs or by beating them to the prize in Xanathar’s Lair (see below).

Therefore, we’re going to break down the heist structure for this lair, just like all the others.

It’s also an unusual lair because it really consists of four distinct areas:

- The docked ships Hellraiser and Hellbreaker

- The Sea Maidens Faire carnival which is erected on the pier between the two ships

- The flagship Eyecatcher anchored in the harbor

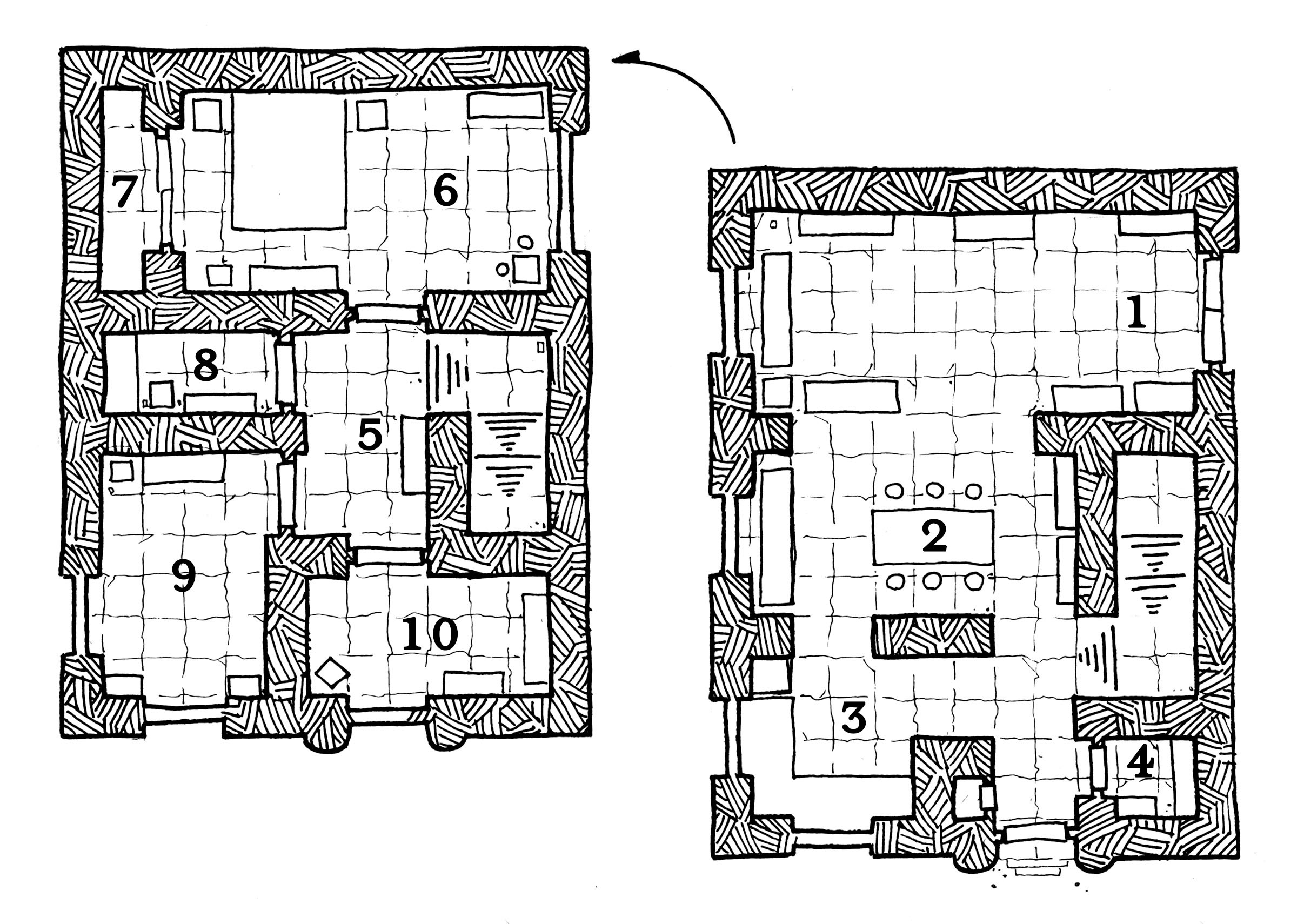

BLUEPRINT NOTES

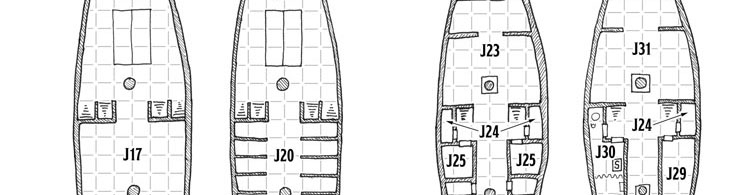

Unlike a city building, there won’t be any plans of Jarlaxle’s ships readily available. However, it’s relatively easy to keep them under surveillance. I recommend preparing a player’s copy of the ship maps which includes the upper decks and the portholes on the lower decks.

EVENT SCHEDULE

CARNIVAL PARADES: The Sea Maidens Faire carnival goes on five different parades during its stay in Waterdeep.

- Ches 10th, announcing its arrival

- Ches 21st, participate in the Twin Parades of Selûne Sashelas

- Ches 25th, parade to Shipwrights’ House and then set up local attractions for the evening as part of the Shipwrights’ Ball (Jarlaxle’s agents happily use the occasion to infiltrate this important social event)

- Tarsakh 1st, join the Caravance holiday parade

- Tarsakh 5th, a special midnight parade during Goldenight

During the parades, the Sea Maidens Faire attractions are shut down and the ships themselves are depopulated (see the Parade adversary roster, below).

ZORD’S BUSINESS: At irregular intervals, Jarlaxle (as “Captain Zord”) will leave the Eyecatcher. On these occasions his rowboat can be seen docking at the Sea Maidens Faire pier, and then he and his group will move off into the city on various errands (often splitting up).

During these times, the following characters should be stricken from the Eyecatcher’s adversary roster:

- Jarlaxle

- Margo Verida & Khafeyta

- Any lieutenants who would otherwise be present on the ship

- 1d3 mates

- 1d6+2 sailors

Although these expeditions cannot be easily planned for, when they occur the Eyecatcher will be substantially less guarded than under normal circumstances.

END OF THE SEA MAIDENS FAIRE: On Tarsakh 20th, the Sea Maidens Faire packs up and sails out of Waterdeep harbor. (If the business of the Grand Game has not been concluded, then it’s likely that Jarlaxle will remain behind with a team of operatives.)

SURVEILLANCE OPPORTUNITY

The drow generally don’t bring strangers onto the ship, and although it may seem like there’s a lot of chaos where the carnies are concerned, the truth is that they’ve been journeying together long enough that everyone pretty much knows each other on sight. Other than becoming one of Jarlaxle’s “romantic” conquests, the PCs are unlikely to get onboard any of the ships under any sort of legitimate pretenses in order to conduct surveillance. However, there are a couple of options which can offer comparable information.

SEA MAIDENS FAIRE: The carnival itself, operating on the pier between the ships, runs from mid-morning until late into the night. This provides the perfect cover for those interested in keeping the Heartbreaker and Hellraiser under surveillance. This surveillance position is able to:

- Identify the total number of crew on each ship — 1 captain, 3 mates, 17-18 sailors, 16 carnies (when they’re not working on the dock; a handful onboard taking breaks at any given time when the carnival is operating)

- Find opportunities to peer in through portholes and get some knowledge of the interior layout of the ship(s)

- Intuit that the Heartbreaker and Hellraiser are virtually identical in layout, suggesting that the same is also likely true of the Eyecatcher

- Note that the Eyecatcher goes on full alert when a local yacht steers too close, but has no reaction to rowboats from the Heartbreaker or Hellraiser approaching

THE DRAGON ZELIFARN: As described in Dragon Heist on p. 145, the dragon Zelifarn is a curious young bronze dragon who wants the PCs to investigate the submarine attached to the bottom of the Eyecatcher and learn nothing in particular about it for no particular reason.

We’re going to swap that up a bit: If Zelifarn spots the PCs surveilling Jarlaxle’s ship, he’ll approach them with a request for help. (If the PCs spot Zelifarn watching Jarlaxle’s ship without being detected themselves, they might also choose to approach the dragon.)

We’re going to swap that up a bit: If Zelifarn spots the PCs surveilling Jarlaxle’s ship, he’ll approach them with a request for help. (If the PCs spot Zelifarn watching Jarlaxle’s ship without being detected themselves, they might also choose to approach the dragon.)

Zelifarn’s mother was, in addition to being a dragon, a master crystalmancer. Jarlaxle and his agents killed his mother, Asphosis, and stole from her the special crystal ball that he uses to spy through the nimblewrights. Zelifarn doesn’t know exactly what the crystal ball does, but he wants it back so that he can restore his mother’s horde. Zelifarn knows that Jarlaxle keeps it in the Scarlet Marpenoth, but hasn’t been able to figure out a way to get it by himself.

By default, Zelifarn would prefer to pay the PCs to do the work for him. They may be able to convince him to actively assist in their raid on the Eyecatcher with a Charisma (Persuasion) check.

(This counts as a surveillance opportunity because the PCs can learn about the existence of both the submarine and the crystal ball from Zelifarn.)

SPECIAL EVENTS: These events may be observed if the PCs are keeping the Sea Maidens Faire under long-term surveillance.

- Escaped Bear (DH p. 146) – evening

- Lieutenants Meet with Laeral (DH p. 145) – night

THE SHIPS

Area J18 (Eyecatcher Only) – Nimblewright Storage: Each of these cabins contain 4 deactivated nimblewrights.

- GM Note: These are the nimblewrights which Jarlaxle has not yet sold. The process for activating them can be intuited with 5 minutes of work and a DC 18 Intelligence (Arcana) test. Jarlaxle and his lieutenants all know the procedure and can activate one of the nimblewrights with a single action.

Area J29 (Eyecatcher Only) – Guest Cabin: A small bag of multihued dragon scales has been strewn across the bed (or is kept in a small bag in the bedside table). Jarlaxle uses them like other people might use rose petals.

Area J30 – Zardoz Zord’s Cabin: In addition to the normal entry for this area, a small desk contains a variety of papers. Among these is the Ledger of Nimblewright Sales (see Part 5) and, if Jarlaxle has become involved in the Grand Game, A Report on the Cultists of Asmodeus and Jarlaxle’s Report on the Grand Game.

- Report on the Cultists of Asmodeus: This report compiles information from a number of different sources – most contemporary, although a few surprisingly historical – exploring indications that there is a well-established cult of Asmodeus “which has infiltrated the highest strata of Waterdhavian society”. After what appears to be a considerable amount of legwork, the report identifies a house on Aveen Street in the North Ward as being a secret front for one of the cult’s shrines. This does not appear to be the center of worship, however. That distinction, according to references in some of the documentation captured from the Asmodean cultists over a century ago, appears to belong to an ancient site of worship located below the Sea Ward. A recommendation is made that gaining access to the records of the Suveyors’, Map-, and Chart-makers’ Guild might prove useful in identifying this site, although likely only if its location could be narrowed down.

- GM Note: The house on Aveen Street is the Asmodean Shrine (a Cassalanter outpost). The “ancient site of worshgip” lies beneath Cassalanter Villa.

Area U3 – Soluun’s Stateroom: The footlocker contains A Letter from N’arl.

- A Letter From N’arl: “Brother—I hope this letter finds you in good spirits. Thank you for the evening at the Seven Masks last tenday. A delightfully bloody affair. I think it wonderful that Jarlaxle has decided to purchase the theater, even if his intentions are not purely artistic. It was quite a joy to escape from Xanathar’s lair for a few hours and remember who I truly am. It’s a pity that we can’t do it more often, but the risk of X discovering my true allegiance is simply too great. On that note, I have taken some pains to arrange assurances for myself. When the time comes, I’ll be able to bring this whole wretched ant’s nest down on that floating fool’s head. – N’arl Xibrindas”

Area U4 – Jarlaxle’s Stateroom: In addition to the normal entry for this area, a crystal ball sits upon a plush cushion of black velvet on a pedestal at the foot of the bed. This is the Nimblewright Crystal Ball (see Part 5).

ADVERSARY ROSTERS

HEARTBREAKER (CARNIVAL ANIMALS)

| 1 mate + 3 sailors | Area J1 - Main Deck | |

| 2 mates | Area J3 - Mates' Cabin | (off-duty, unarmored) |

| 4 sailors | Area J4 - Crew Cabins | (1 per cabin, off-duty, unarmored) |

| Cook (Commoner) | Area J5 - Gallery | |

| 6 sailors + 1d4 carnies | Area J7 - Dining Cabin | |

| 2 sailors | Area J9 - Aft Castle (Lower) | |

| Captain* + Nimblewright | Arae J10 - Captain's Cabin | |

| 2 sailors | Area J11 - Aft Castle (Upper) | |

| 1d8 carnies | Area J14 - Carnies' Cabins | (resting, 16 sleeping at night) |

| 1 sailor (25%) | Area J15 - Brig | (in cell) |

| 1d2 Animal Handlers (Commoners) | Area J20 - Creature Pens | (animals present only at night) |

| 2 drow gunslingers | Area J23 - Gunslingers' Hold |

HELLRAISER (PARADE FLOATS)

| 1 mate + 3 sailors | Area J1 - Main Deck | |

| 2 mates | Area J3 - Mates' Cabin | (off-duty, unarmored) |

| 4 sailors | Area J4 - Crew Cabins | (1 per cabin, off-duty, unarmored) |

| Cook (Commoner) | Area J5 - Gallery | |

| 6 sailors + 1d4 carnies | Area J7 - Dining Cabin | |

| 2 sailors | Area J9 - Aft Castle (Lower) | |

| Captain* + Nimblewright | Arae J10 - Captain's Cabin | |

| 2 sailors | Area J11 - Aft Castle (Upper) | |

| 1d8 carnies | Area J14 - Carnies' Cabins | (resting, 16 sleeping at night) |

| 1 sailor (25%) | Area J15 - Brig | (in cell) |

| 2 drow gunslingers | Area J23 - Gunslingers' Hold |

EYECATCHER (FLAGSHIP)

| 1 mate + 3 sailors | Area J1 - Main Deck | |

| 2 mates | Area J3 - Mates' Cabin | (off-duty, unarmored) |

| 4 sailors | Area J4 - Crew Cabins | (1 per cabin, off-duty, unarmored) |

| Cook (Commoner) | Area J5 - Gallery | |

| 6 sailors | Area J7 - Dining Cabin | |

| 4 giant spiders | Area J17 - Lower Cargo Hold | MM p. 328 |

| 2 sailors | Area J9 - Aft Castle (Lower) | |

| Captain* + Nimblewright | Area J10 - Captain's Cabin | |

| 2 sailors | Area J11 - After Castle (Upper) | |

| Random response team (25%) | Area J14 - Cabins | (resting) |

| 1 sailor (25%) | Area J15 - Brig | (in cell) |

| 8 Nimblewrights | Area J18 - Storage | (deactivated) |

| Margo Verida + Khafeyta + Jarlaxle (25%) | Area J29 - Guest Cabin | |

| Jarlaxle (26-50%) + Nimblewright | Area J30 - Zardoz Zord's Cabin | |

| 5 attack mannequins | Area J31 - Training Area | |

| Jarlaxle (51-00%) | Area J32 - Jarlaxle's Sauna |

SCARLET MARPENOTH

| Soluun Xibrindas (50%) | Area U3 - Soluun's Stateroom | with a half-elven torture victim (25%) |

| Fel'Rekt Lafeen (50%) | Area U5 - Fel'Rekt's Stateroom | |

| Krebbyg Masq-il'yr (50%) | Area U6 - Krebbyg's Stateroom | |

| 3 gnome engineers + 2 mates | Area U7b - Command Center | |

| 4 gnome engineers | Area U8 - Engineers' Staterooms |

* Has key to captain’s trunk and all doors on their ship.

ADVERSARY ROSTER – DURING PARADE

HEARTBREAKER (CARNIVAL ANIMALS)

| 1 mate +1 sailor | Area J1 - Main Deck | |

| 2 mates | Area J3 - Mates' Cabin | (off-duty, unarmored) |

| 4 sailors | Area J4 - Crews' Cabins | (1 per cabin, off-duty, unarmored) |

| Cook (commoner) | Area J5 - Gallery | |

| 2 sailors | Area J9 - Aft Castle (Lower) | |

| Captain* + Nimblewright | Area J10 - Captain's Cabin | |

| 2 sailors | Area J11 - Aft Castle (Upper) | |

| 1 sailor (25%) | Area J15 - Brig | (in cell) |

| 2 drow gunslingers | Area J23 - Gunslingers' Hold |

HELLRAISER (PARADE FLOATS)

| 1 mate + 1 sailor | Area J1 - Main Deck | |

| 2 mates | Area J3 - Mates' Cabin | (off-duty, unarmored) |

| 4 sailors | Area J4 - Crew Cabins | (1 per cabin, off-duty, unarmored) |

| Cook (Commoner) | Area J5 - Gallery | |

| 2 sailors | Area J9 - Aft Castle (Lower) | |

| Captain* + Nimblewright | Area J10 - Captain's Cabin | |

| 2 sailors | Area J11- Aft Castle (Upper) | |

| 1 sailor (25%) | Area J15 - Brig | (in cell) |

| 2 drow gunslingers | Area J23 - Gunslingers' Hold |

EYECATCHER (FLAGSHIP)

| 1 mate + 3 sailors | Area J1 - Main Deck | |

| 2 mates | Area J3 - Mates' Cabin | (off-duty, unarmored) |

| 4 sailors | Area J4 - Crew Cabins | (1 per cabin, off-duty, unarmored) |

| Cook (Commoner) | Area J5 - Gallery | |

| 4 giant spiders | Area J17 - Lower Cargo Hold | MM p. 328 |

| 2 sailors | Area J9 - Aft Castle (Upper) | |

| Captain* + Nimblewright | Area J10 - Captain's Cabin | |

| 2 sailors | Area J11 - Aft Castle (Upper) | |

| Random response team (25%) | Area J14 - Cabins | (resting) |

| 1 sailor (25%) | Area J15 - Brig | (in cell) |

| 8 Nimblewrights | Area J18 - Storage | (deactivated) |

SCARLET MARPENOTH

| Soluun Xibrindas (50%) | Area U3 - Soluun's Stateroom | with a half-elven torture victim (25%) |

| Fel'Rekt Lafeen (50%) | Area U5 - Fel'Rekt's Stateroom | |

| Krebbyg Masq-il'yr (50%) | Area U6 - Krebbyg's Stateroom | |

| 3 gnome engineers + 2 mates | Area U7b - Command Center | |

| 4 gnome engineers | Area U8 - Engineers' Staterooms |

* Has key to captain’s trunk and all doors on their ship.

STAT REFERENCE

Jarlaxle Baenre – DH p. 206

Margo Verida – female Amnian human bard (DH p. 195)

Khafeyta – female Mulhorandi human swashbuckler (DH p. 216)

Captain – drow mage, MM p. 129 (prepare sending instead of fly)

Mates – drow elite warrior, MM p. 128

Mates – drow elite warrior, MM p. 128

Sailors – drow, p. 128

Carnies – commoners, MM p. 345

Gnome Engineers – apprentice wizards, DH p. 194

- NG, Small, 7 (2d6) hp

- Racial Traits: Advantage on Int, Wis, Cha saving throws vs. magic. Walking speed 25 ft. Darkvision 60 ft. Speak Common and Gnomish.

- Names: Lorella Middenpump, Tervaround Waggletop, Anverth Levery, Cockaby Fapplestamp, Ellywick Fiddlefen, Gerbo Reese, Zaffrab Horcusporcus

Nimblewright – DH p. 212

Drow gunslingers – DH p. 201

QUESTIONING CREW

- Captains: Dragon Heist, p. 132

- Sailors: Dragon Heist, p. 132

- Carnies: Dragon Heist, p. 132

- Margo / Khafeyta: Dragon Heist, p. 140

- Gnome Engineers: Dragon Heist, p. 141-142

Area 2 – Dining Room: Those here for gladiatorial gatherings are brought together in this room for light socializing and the enjoyment of various delicacies placed upon the table. (Roasted bulette with rare Shou Louan spices.

Area 2 – Dining Room: Those here for gladiatorial gatherings are brought together in this room for light socializing and the enjoyment of various delicacies placed upon the table. (Roasted bulette with rare Shou Louan spices.