IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

SESSION 37D: AFFAIRS OF THE EVENING

May 9th, 2009

The 20th Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

ILTUMAR’S INTERVENTION

They quickly explained the situation to Lavis, who seemed both shocked and saddened by what Iltumar had done (and was doing).

“Will you help us?” Tee asked. “We want to stage an intervention for him.”

Lavis agreed. They went back into the room where Iltumar was still lying unconscious on the surgical table and woke him up.

“Tee? Lavis? What are you doing here?”

“We came to help you, Iltumar,” Tee said.

“Help? I don’t need help!”

“Look at what you’ve done to yourself.” She gestured at his hands.

Iltumar looked down. He was horrified by the mutilation. “What happened?”

“This is what they were trying to do to you.”

“No! They were going to make me stronger so that I could help people!”

Confused, dazed, and in a fair amount of pain, Iltumar was also steeped in denial. But when they brought in Lavis a few minutes later, he broke down completely.

“I just wanted to help people…” he murmured.

Lavis patted him awkwardly on the shoulder.

They seemed to have gotten through to him, but they weren’t sure it was going to stick.

“As soon as we let him go, he’ll just go running back,” Elestra said.

Tor nodded. “And even if he doesn’t, they’ll be looking for him. It’s not safe for him to go home.”

“Or anywhere,” Tee agreed.

SQUIRING ILTUMAR

They eventually decided to send him to Pythoness House. “If he really wants to do good,” Tor said, “Then maybe Sir Kabel can give him the chance.”

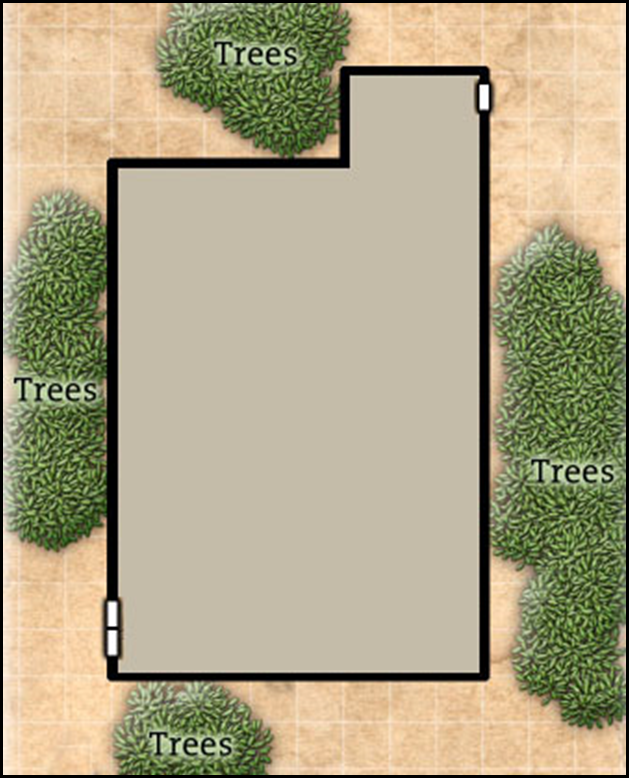

While the others returned to the Ghostly Minstrel, Tee bundled Iltumar into a carriage and took him to Pythoness House. The place was quickly being transformed: One corner of the courtyard, which was bustling with activity, had been stacked high with refuse cleaned out from the inner rooms of the keep. Guards were now posted openly at the gate and they were able to direct Tee to where Sir Kabel was overseeing the refurbishing of one of the chambers on the second floor.

Tee gave Kabel a terse summary of Iltumar’s situation and his desires. Kabel agreed to shelter the boy in Pythoness House, with an eye towards squiring him into the Order if he proved worthy.

Once Kabel had sent Iltumar away with one of his knights to get him sorted away, however, Tee turned back to him. “I didn’t want to say anything in front of him, but you should know that it’s possible you shouldn’t trust him. I think he’s all right, but he fell in with a bad crowd. And they’ll be looking for him. He shouldn’t be allowed to leave Pythoness House.”

Kabel nodded. “That shouldn’t be problem.”

Tee took a deep breath. “There’s something else.”

Kabel quirked an eyebrow. “Oh?”

“We spoke with the Commissar about Dominic’s plan to denounce Rehobath.”

“What?” Kabel was less than happy.

“The Commissar was concerned. And I think he’s got good reason for it.”

Kabel shook his head. “If Rehobath didn’t know before, he almost certainly knows now.”

“I don’t think the Commissar would tell him. He’s already annulled the warrant for your arrest.”

“It’s not a matter of who might tell him, it’s a matter of how many people know. And the list keeps growing.” Kabel grew thoughtful, but there was still an undercurrent of anger. “We’ve already talked about moving up the date of the announcement.”

“I thought you were going to wait for the Silver Fatar?”

“That may not be possible now.”

AFFAIRS OF THE EVENING

When the others returned to Delvers’ Square, Agnarr stopped by the Bull and Bear to let Hirus know that Iltumar and Lavis had both been rescued and that Iltumar was being kept in a safe place. Hirus thanked him profusely. Agnarr, made slightly uncomfortable by the show of gratitude, smiled, grunted, and excused himself.

Tor went to the stables, saddled Blue, and spent the next half hour riding up and down Tavern Row. He had some sense of keeping an eye out for any signs of gang activity between the Killravens and Balacazars, but the tension on the street was palpable. Members of the City Watch were posted everywhere, and after Tor’s third or fourth circuit he was approached by some of the guards and asked his business. When he wasn’t able to give a satisfactory answer, they told him to “be about your lack business elsewhere” (with a long look of askance at the red sash he wore).

After leaving Pythoness House, Tee headed to the White House. There she found the two soldiers who had fleeced Agnarr earlier in the day and, settling herself at their table, managed to win 15 of the gold pieces back from them. After they had decided to call it a night (“You see? I told you there wouldn’t be any barbarians here!”), she shifted over to the high stake tables and – on a string of good luck – won 300 gold pieces.

ILL NEWS FROM THE PRISON

(09/21/790)

Tee and Ranthir both rose early the next morning and went shopping for potions. (Without Dominic’s divine aid, they needed more healing resources.) By the time they returned to the Ghostly Minstrel, the others were awake and they breakfasted together.

The Freeport’s Sword was due to arrive that day, but – as Tee had learned – it was unlikely to arrive until the afternoon. They decided to spend the morning attending to minor chores and the like.

Elestra decided to spend the morning gathering information from around town. But as soon as she walked out the door and bought a newssheet, she turned right around and went back inside.

“Shilukar has escaped.”

“What?!”

It was true. Shilukar had disappeared from his cell in the Prison. Warden Odsen Rom swore that the thief-mage had not escaped, but he was also forced to confess that his guards had no idea where Shilukar might be hiding within the Prison complex, either.

“He’s going to come looking for us,” Agnarr said.

“Not if he can’t get out of the prison,” Elestra said.

“If they couldn’t keep him in his cell, how likely is it they’ll keep him in the prison?” Tee asked.

“If he hasn’t gotten out already,” Tor said.

They talked about it a little longer, but there didn’t seem to be anything they could do about it. And they weren’t even sure they wanted to do anything about it: Shilukar had neither the Idol of Ravvan nor the cure for Lord Abbercombe. He might come after them, but they had no reason to pursue him. He was somebody else’s problem.

FILLING THE MORNING HOURS

Tor had another round of training scheduled at the Godskeep. He found that the work of repositioning a bulk of the Order to the Holy Palace was still under way, but the halls already seemed emptier and it felt as if the hectic activity of the day before was beginning to die down.

Agnarr headed back to the Bull and Bear for the third time. He still needed to find a suit of armor for Seeaeti, having been caught up in the Iltumar affair the first time he’d gone and deciding that it wasn’t the best time to broach the subject the second time.

He found Hirus in a welcoming and appreciative vein. He thanked Agnarr again for all the help he had given Iltumar, and when Agnarr explained what he was looking for he became thoughtful for a moment.

“I bought a suit of damaged mage-touched chain yesterday,” he said after a moment. “There’s a large section of it missing. Repairing it would be a major undertaking, but it would be much easier for me to modify it for your hound.”

“How much?” Agnarr asked.

“Oh, no! This is the least I can do to show my thanks!” Hirus waved his hands. “I’ll have it ready for you in four days.”

TEE’S INCENSE VISION

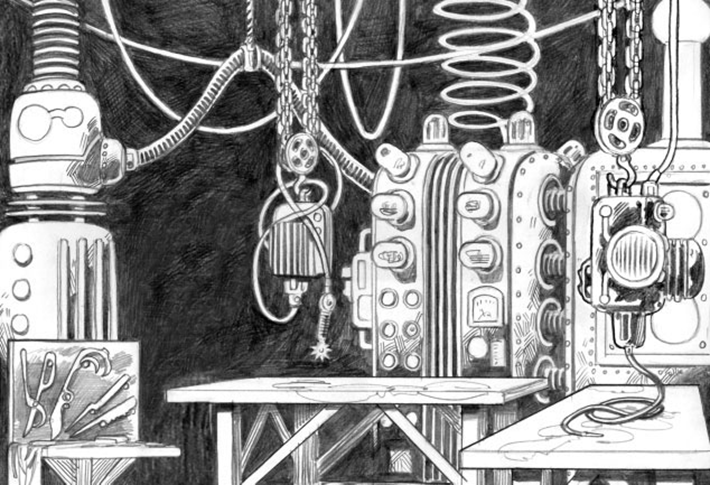

Tee, finding herself with a free block of time for the first time in days, was feeling experimental. She took out the vision incense they had found in Pythoness House and carefully prepared her room for the ritual Ranthir had described to her.

The burning incense had a pleasing scent which pulled her quickly and easily into a trance-like state. But then, suddenly, the scent turned to brimstone in her nostrils.

Her eyes snapped open.

She found herself in a hellish scene. Black, basalt rock extended off to a featureless horizon. A single, pale star glinted in the sky, providing a dim radiance. Standing twenty feet before her was a writhing globe of flesh and body parts. Mouths appeared on the globe, moaning and howling in pain.

After a few a moments, a sickening rending noise ripped its way free from the globe as the fleshy substance was torn apart. Stepping out of the rented, deflating side came a massive, black reptilian with a single, cyclopean eye of sickly yellow.

“AT LAST… YOU HAVE COME TO THE VAULT OF TSATHZAR RHO… MAY SESSURAL FEAST UPON YOUR DREAMS!”

She became aware of Agnarr screaming in her ear: “Tee! Tee! What is it? What’s wrong?”

Running the Campaign: Losing a PC – Campaign Journal: Session 37E

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index