DISCUSSING

In the Shadow of the Spire – Session 38A: The Arathian Job

Once Agnarr’s tail-lopping duties were completed, they loaded the various ratmen corpses – along with the Iron Mage’s crate – into the cart Elestra had procured and started the long haul up the Dock ramp.

As they went, they mulled the question of how they could protect the Iron Mage’s crate. It was too large and too dangerous for them to haul around with them, and it certainly wasn’t the sort of thing they could just leave lying about their room.

They rejected a plan to place illusions on the ratbrute corpses to make them appear like duplicates of the real crate before dumping them in the Midden Heaps or scattering them around town. They felt it was a ruse too easily penetrated… and once the illusions lapsed the corpses might lead to some unwanted questions on their own account.

“Besides,” Tor pointed out. “I promised to dispose of them properly.”

What the players decided to call the Arathian Job (it’s like The Italian Job, but we’re in Arathia!) isn’t the classic image of what a heist looks like, but it has the same attitude: Planning, prep work, execution.

And as you look at the Arathian Job as a heist, you might find it remarkable that it just… works. The players simply put together their plan and executed it.

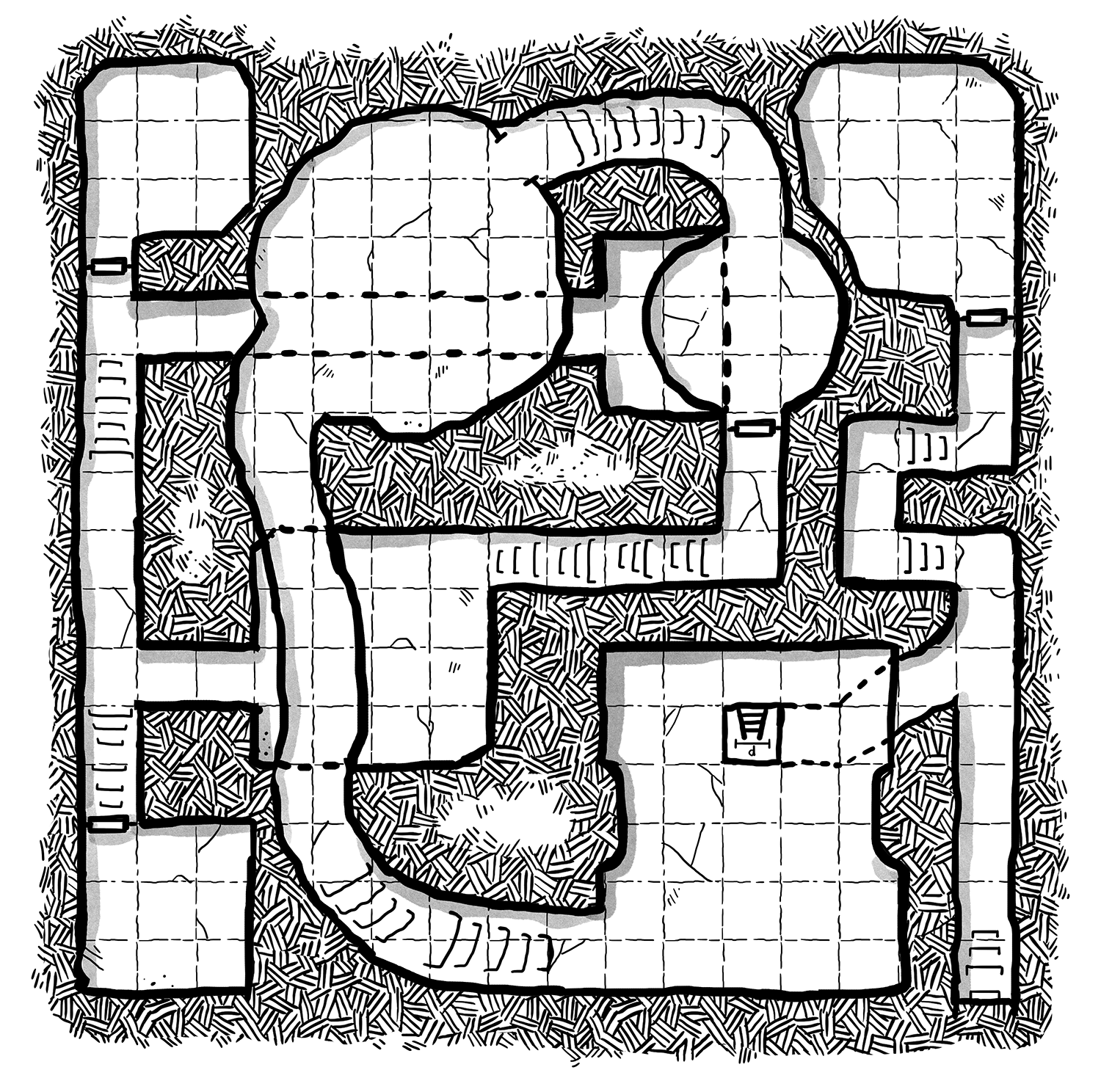

If you look back at Session 8, when the PCs were hired to sneak a scrying cube into Linech Cran’s office, you’ll see a similar dynamic:

Once there, Tee went down the narrow alley between the Yebures’ and the house next door. From there she climbed quietly onto the Yebures’ roof. She had some difficulty climbing the next section of wall up to Linech’s window – falling and cracking her head once – but she eventually secured a grappling hook in the chimney on Linech’s roof, climbed the rope, and then rappelled over to Linech’s window.

The lock on Linech’s window yielded to her thieves’ tools easily enough and she slipped inside, falling to the floor next to the life-size gold statue they had noticed the last time they were in the office.

In looking for a place to hide the scrying cube, Tee’s eyes were naturally drawn to the bookshelves along the room’s north wall. Clearing some of the books away she reached back to place the scrying cube behind them… only to find a crumpled up sheet of paper lying there. She pulled this out, glanced at it, and then stuffed it into her bag. Placing the scrying cube and then carefully replacing the books she had moved, she went back to the window, shut it behind her, and climbed down.

Tee gave the signal that the others, scattered around the lower burrow, could disperse. It had all gone as smoothly as anyone could hope.

They’d done their legwork, come up with a plan that worked, made their skill checks, and walked away clean.

It can be tempting, as a GM, to think that if we don’t make things hard for the PCs or complicated in some way that the game will be “boring.” That might be true if every challenge is trivial and the PCs simply streamroll their way through the campaign, but the reality is that coming up with a strategic plan, executing it, and having it work is immensely satisfying.

So when the players earn a victory, let them bask in it.

These successes also create great contrast for when things DO fall part. You can see a very clear example of this in the case of the Linech Cran job because in Session 9 the PCs had to come back and break into his office all over again, this time to steal the gold statue he had on display there. This time there were new complications (someone else was trying to break into the office at the same time), and the PCs ended up flubbing one of their skill checks and dropping the statue, creating a loud noise that raised the alarm and created even more complications. The PCs were still ultimately successful, but it was a much more stressful heist.

The great thing about this contrast is — if you’re playing fair — then the players truly feel like they earned their victories (because they did), which makes them even sweeter. And the players also own their struggles and even failures: There’s no reason the second Linech Cran job couldn’t have gone smoothly. (The first job proves it, after all.) The complications they need to overcome (like dropping the statue) feel legitimate, partly because they are and partly because they’ve seen the proof of that. That legitimacy keeps the players immersed in the scenario, and also makes their ultimate success (assuming they achieve it) all the more satisfying because they earned it.

By contrast, when the players become convinced that they can never truly succeed because the GM will always find some way to thwart their best laid plans (whether in the name of “making things interesting” or otherwise), it steals the luster of the campaign. It’s the reason some players don’t enjoy making plans; after all, what’s the point when every plan is doomed to failure whether it’s good or bad? And other players will respond by spending even more time making plans in a Sisyphean and ultimately doomed effort to make them perfect. (And this, too, becomes a reason why players don’t enjoy making plans.)

The same thing is even more, in my experience, if the players becomes convinced that they can never fail because the GM will always twist things to make sure they succeed. Again: Why bother making plans if making the plan has no meaningful impact on the outcome?

And what happens as a result is that the tactical and strategic elements of the game become deeply weakened: Figuring out what you need to do and then doing it is in fun in games, it’s fun in life, and it should be fun in an RPG.

When that thrill gets pulled out of your roleplaying game, it’s a sad loss.

Campaign Journal: Session 38B – Running the Campaign: Adding a New Player (Part 2)

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index