DISCUSSING

In the Shadow of the Spire – Chaos Lorebook: Lore of the Demon Court

Its face was like the mirror nothingness. Its gaze a river of fire that touched thought but not earth.

Above all Those Who Slumber was the power of the One Who Was Born of Destruction, the Song Render, the Ender of Souls, the Dweller in Darkness. And among those who would speak his name, his name was Shallamoth Kindred – the act of desolation given life and mutilation given flesh.

And he did move with the quickness of a razor.

In the palace of the Kindred of Shallamoth, the eyes of the Galchutt are shut.

In the Temple of the Ebon Hand, the PCs discovered a cache of lore books.

These are specifically part of what I refer to as the chaos lorebooks, a collection of roughly fifty different lore books in the campaign dealing with:

- chaos cults

- chaositech

- the demon court

- servitors of the Galchutt

- the elder brood

- Wuntad’s plans for the Night of Dissolution

The root of this collection is the Book of Faceless Hate, which looks like this in my version of the lore book:

THE BOOK OF FACELESS HATE

No title marks the tattered, dark brown cover of this book. Its contents are written in a nearly illegible scrawl that could only have been born of hopeless madness. The first several pages of the book are covered in repetitions and variations of a single phrase: FACELESS HATE. (They wait in faceless hate. We shall burn in their faceless hate. The faceless hate has consumed me. And so forth…)

CHAOS: True chaos, or “deep chaos”, is a religion based on the fundamental aspects of hate, destruction, death, and dissolution. The philosophy of chaos is one of constant and endless change. It teaches that the current world is a creation of order and structure, but that it was flawed from the dawn of time due to the lack of foresight into what living sentience truly wants and need. The gods of creation – the gods of order – are untouchable and unknowable. They are aloof and uncaring, says the teaching of true chaos.

THE LORDS OF CHAOS: According to the book, the Lords of Chaos – or “Galchutt” – are gods of unimaginable power. But they are “mere servants of the true gods of change, the Demon Princes”. It is written that the Galchutt came to serve the Princes during the “War of Demons”, but while the Princes have “left this world behind”, the Galchutt still “whisper the words of chaos”.

VESTED OF THE GALCHUTT: Although they sleep, the Galchutt still exert some influence upon the world. This influence can be felt by the faithful through the “touch of chaos” and the “mark of madness”, but it can also be made manifest in one of the “Vested of the Galchutt” – powerful avatars of their dark demi-gods’ strength.

CHAOS CULTS: The book goes on to describe (but only in the vaguest of terms) many historical and/or fanciful “cults of chaos” which have risen up in veneration of either the Galchutt, the Vested of the Galchutt, or both. These cults seem to share nothing in common except, perhaps, the search for the “true path for the awakening of chaos”. The book would leave one with the impression that the history of the world has been spotted with the continual and never-ending presence of these cults – always operating in the shadows, save when bloody massacres and destruction bring them into the open.

As originally presented in Monte Cook’s Night of Dissolution (p. 93), the Book of Faceless Hate was a much more comprehensive player briefing of the entire cosmology of chaos in the Ptolus setting. I knew that I would need to create my own version of the book because I had moved Ptolus to my campaign world, and was therefore adapting this cosmology and melding it to my cosmology.

But I also knew that I wanted to make the Book of Faceless Hate more enigmatic, creating a much larger conspiracy and mystery that the PCs would need to unravel: How many cults were working with Wuntad? What were their true intentions? What was the true nature and secret history of the “gods” they worshipped?

My motivation was partly aesthetic: I just thought the chaos cults would be a lot cooler if they were drenched in mystery.

But it was also practical. Doing a big data dump to orient the players in the opening scenario of the published Night of Dissolution makes sense, because it was a mini-campaign with five scenarios, but I was planning a much larger exploration of the chaos cults that would involve a couple dozen scenarios. If I gave the players a comprehensive overview of who the cults were and everything they were doing, then the rest of the campaign would just become a rote checklist. It would be difficult to maintain a sense of narrative interest and momentum, and things would likely decay into “been there, done that.”

I also knew that if the players were forced to piece together disparate lore, slowly collecting different pieces of evidence to eagerly weave together while collecting the leads they need to continue pursuing their investigation and pasting all of it onto a literal or figurative conspiracy board, that it would get them deeply invested in the chaos cults. It would make them care.

(And when the players started holding lore book meetings and discussing the chaos cults even when we weren’t playing the game, I knew I’d pulled it off.)

DISTRIBUTING THE BOOKS

So I broke up The Book of Faceless Hate into a bunch of pieces, adapted the content to my campaign world, and reframed everything using lore book techniques so that the players would feel like they were “really” reading these strange tomes and oddly moist pages. Then I started adding even more lore books to flesh things out more, ending up with, as I mentioned, roughly fifty different books.

Okay, but what did I actually do with all of these lore books?

The short answer is that I seeded them into all the adventures in the campaign, spreading them around so that the PCs would collect them book by book.

I had about twenty chaos-related adventures where these books could be found, so this meant that many of them would be stocked with multiple lore books. Sometimes they were clustered together in a secret library; other times they would be scattered throughout the adventure.

In practice, I had even more options (and was adding even more chaos lorebooks) because most of these books weren’t unique volumes. They were books and religious scriptures. Secretive, yes, but still meant to be copied and disseminated. Thus, for example, the PCs could find a copy of The Touch of the Ebon Hand in Pythoness House in Session 22, but also, unsurprisingly, later find a bunch of them in the Temple of the Ebon Hand.

Note: And because I wasn’t worried about duplicating them, the PCs went off into an unexpected direction and I ended up adding new scenarios, I could easily reach into my stock of chaos lorebooks, grab a few, and sprinkle them around.

I was also able to add them to other scenarios, unrelated to the chaos cults, to make the entire campaign world feel like a unified whole and create the impression that the chaos cults were a pervasive, ever-present influence.

Along these same lines, I realized it was generally ideal if a cult’s primary lorebook could be found OUTSIDE the cult’s headquarters. In other words, if it was possible for the PCs to learn about a cult (setup) and then later discover where they were operating (payoff).

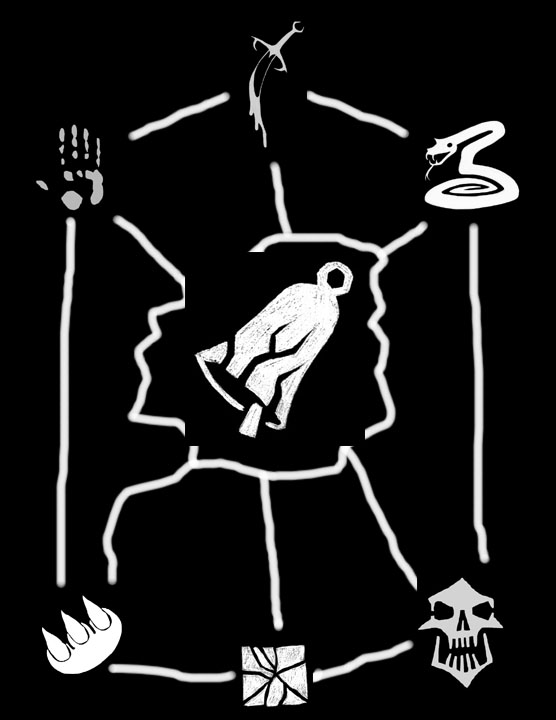

Consider, also, this diagram, also found in Pythoness House in Session 22:

It depicts the symbols for a variety of chaos cults working with Wuntad, giving a default structure of:

- Who does this symbol belong to?

- It belongs to X!

- We found where X is / what X is doing!

You can see the simple progression of setups and payoffs that lead to a satisfying conclusion, and in this case we’ve complicated things through the simple expedient of having seven iterations of this progression happening simultaneously and overlapping with each other.

In actual practice, though, I muddied things up a bit more by

- including a couple symbols on the diagram that the PCs would never actually encounter in the campaign (where are they?!); and

- writing up lorebooks describing several additional chaos cults that weren’t part of Wuntad’s scheme at all (how many of them are there?!).

But I digress. Let’s get back to how the lorebooks were distributed.

What I quickly realized was that I needed a plan. You need to remember that I wasn’t prepping the entire campaign ahead of time: I had created an adventure track that indicated what the individual adventures were and how they were linked to each other, but I was prepping the keys for those adventures as they became relevant. Although I started off by simply adding whatever chaos lorebooks made sense in a particular adventure, it became clear that

- there was a bias towards some of the lorebook topics, causing them to be over-represented; and

- with so many lorebooks in play, there was a real risk that I would lose track and fail to place some of the lorebooks.

I started by putting together a simple checklist (i.e,. Have I placed this lorebook yet?), but realized I could still end up writing myself into a corner. (Where the PCs would get to the end of Act II and I would realize I still had way too many lorebooks to place and not enough adventure to place them in!) So I swapped to a spreadsheet with a list of all the lorebooks and a list of all the adventure cross-referenced.

This let me see and shape the totality of the chaos lorebooks: Where were they concentrated? Which books still needed to be placed and where could they go for best effect? Was it possible to find the book outside of the cult’s own lair?

Note: On this worksheet, I also made a point of distinguishing between which lorebooks had actually been placed – i.e., I’d keyed the adventure and they were in the adventure key—as opposed to which lorebook locations were only planned and had not yet been executed.

While doing this work, I also realized that there was a principle similar to the Three Clue Rule: Most of these lorebooks weren’t structurally essential, but they were — if I do say so myself — really cool, and I’d also put a lot of prep work into them. So for most of the books, I made a point of including them in at least three different adventures. (And if, for some reason, it wouldn’t make sense for a lorebook to be so widely disseminated, I would try to include multiple copies in the adventures where it could logically be found.)

As seen in the current session, this obviously resulted in the PCs often finding copies of chaos lorebooks that they already had. You might think this to be repetitive, pointless, or even disappointing, like a someone saying, “Aw, man… I already have this one!” when opening a pack of baseball cards. In practice, though, that really wasn’t the case.

First, the primary effect was fare more along the lines of, “Oh no… The cult has been here, too.”

Second, because it did, in fact, make diegetic sense for multiple copies of these books to exist, the presence of multiples made the world feel like a real place. It made the books “real,” rather than being a collectibles achievement in a video game.

Finally, because the campaign was being played out over months and even years of real time, the second or third encounter with a chaos lorebook would simply remind the players of what they have, often prompting them to pull out their copy of the handout and review it. Thus, the lore of the campaign was being constantly and organically reinforced until the players knew it in their bones.

Which was, of course, the point of the chaos lorebooks in the first place.

Campaign Journal: The Bloated Lords – Running the Campaign: All Your Zaug Belong to Us

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index