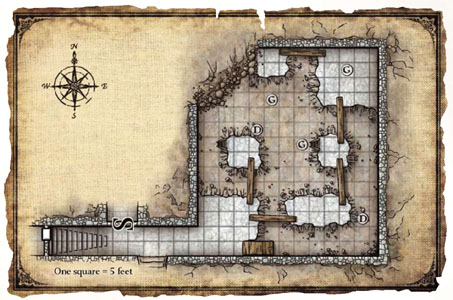

Last week I talked about the importance of a megadungeon in creating an open game table. Today I want to talk a little bit about how that works in practice. I’m going to be using my own experiences running the Caverns of Thracia as an example. Players currently playing in my campaign may wish to avoid reading this, but there’s nothing here which I feel strongly about “forbidding” you from looking at. Except for the reference map, which I’m hiding behind a link:

Last week I talked about the importance of a megadungeon in creating an open game table. Today I want to talk a little bit about how that works in practice. I’m going to be using my own experiences running the Caverns of Thracia as an example. Players currently playing in my campaign may wish to avoid reading this, but there’s nothing here which I feel strongly about “forbidding” you from looking at. Except for the reference map, which I’m hiding behind a link:

REFERENCE MAP – PLAYERS DO NOT LOOK!

The rest of you may want to open that up in a separate tab or window.

An effective megadungeon has three basic components:

1. A map.

2. A starting map key.

3. Wandering monster tables.

The map should be large and thoroughly xandered. Xandering is crucial in a campaign megadungeon because of the complex and dynamic environment it provides: Players need to be free to choose different experiences each time they return to the dungeon. If you force them to trudge down the exact same path each time, the dungeon will have no effective replay value.

The map key should be flavorful and interesting. It will be frequently rewritten, but the starting key should provide a strong foundation for you to build on and a rich soil in which the dungeon can grow. Most old school bloggers I’ve seen tend to advocate minimalistic keys that tend to de-emphasize memorable geography. (For example, the Castle of the Mad Archmage contains key entries like “ORC SERGEANT. (8 h.p.) armed with sword and flail. He has 12 e.p.” and “SECRET CHAMBER. Great skeleton (3 HD, 15 h.p., turns as a ghoul, otherwise as a normal skeleton). Small locked chest holds 75 g.p.”) But I disagree with this approach: The monsters in the dungeon are ephermeral. It’s the geography that’s going to stick around. Minimalist keys are fine, but use them to make memorable locales. (Check out my Halls of the Mad Mage for my own efforts to use a minimalistic key to create interesting locations.)

Wandering monster tables have generally gotten a bad rap in many modern gaming circles. They’re generally considered to be “wasted time”. But when properly employed, wandering monster tables are improv tools and low-tech procedural content generators. (See Breathing Life Into the Wandering Monster for a deeper look at how this works in practice.) Wandering monsters also play an important part in maintaining proper pacing throughout the dungeon complex and help to make the complex “come alive”. In all of these functions, wandering monster tables are playing a vital role in preventing the megadungeon from becoming a place that can be “cleared out”.

Caverns of Thracia, of course, provides all three of these essential elements: Although the reference map I’m using for this essay shows only the small, specific section of the dungeon complex I’ll be discussing in detail, there are, for example, three completely separate entrances into the caverns and the delves described below represent only a fraction of the sessions I’ve run there. Similarly, Jennell Jaquays’ map key positively drips with detail — the unique characters of the Caverns of Thracia seem to ooze out of every room description. Jaquays also provides detailed and dynamic wandering monster tables.

THE FOUNDATION

Let’s start with the basics. Looking at our reference map, allow me to present a very simplified/summarized version of the pertinent map key:

- Walls once painted in brightly color murals. Now home to several hundred bats. The floor is covered a couple feet deep in bat guano.

- Columned hall. More bats and guano.

- Ruined statue, digging rubble pile turns up the face of Athena. More bats.

- Ruined statue of a winged figure. Giant centipedes (x19).

- Ruined statues reduced to complete rubble. Lizardmen hunting party (x4).

- Spear trap.

- Anubian Guardpost. (x6)

- Sloping passage.

42. Rubble-filled cavern. Colony of rats in rubble (raise alarm if disturbed).

43. Guardpost and Pit Traps. Anubians (x4). One of the pits leads to a sub-level with a small, hibernating dragon.

In addition, the module provides two wandering monster tables — one for Level One and one for Level Two. There is a 1 in 10 chance per turn of generating an encounter.

Simple enough, right?

Now, let me show you how I’ve used these simple tools to run 20-30 hours of high quality gaming.

DELVE ONE and DELVE TWO

The first delve is pretty simple and by the book: The PCs entered the dungeon, held their noses at wading through bat dung as they headed through areas 1-3. They found the lizardmen in area 5 who were nursing a comrade who had been injured by the centipedes in area 4 (as described in the adventure key). They killed the lizardmen and then entered area 4 to fight the centipedes themselves. After a nasty fight, they spiked the door shut, dragged the corpses of the centipedes that they had killed out of the dungeon, and returned to the jungle. That night they feasted that night on roasted centipede meat.

When they returned to the dungeon the next day I generated a surface encounter using the Level One wandering monster tables. It turned out to be a rather tough one, featuring a minotaur along with half a dozen dog-faced anubians. What were they doing there? Guarding the entrance. The party’s wizard tried to use a sleep spell, but it failed spectacularly. He ran back to where the others were waiting, but they all dithered long enough for the minotaur to reach them and then it turned rather abruptly into a TPK.

The heads of the PCs were placed on pikes outside the dungeon entrance (where they remain to this day).

DELVE THREE

The players rolled up new characters and ended up entering the dungeon through a different entrance. A few sessions later, however, a different set of PCs returned to this area. They discovered a half dozen anubians (minus the minotaur) standing guard at the entrance. (Another random encounter, which also slotted naturally into the “guarding this entrance” concept.) This time the battle went much better for the heroes and they were able to clear away the freshly positioned guards.

Downstairs they returned to area 3. They could hear noises coming from behind the door to area 5 and saw that the door to area 4 had been spiked shut. They tried to ambush the anubians in area 5 (which had been generated from the wandering monster tables), but the door squeaked when they tried to open it and the anubians were warned. Despite this, they dispatched the anubians.

With their backs secure, they carefully pried up the spikes. Somebody scooped up some bat guano in a skull and tried to use it to grease the hinges and then they threw open the door.

Angry red centipedes looked up at them.

They slammed the door shut and spiked it again.

Exploring the room where the anubians had been, they found the secret door. They turned left, through area 8, and down to the second level. They fought some giant rats in area 42, spotted the guards in area 43, and decided to retreat back to the first level and finish it off.

There they fought and killed the anubians in area 7, looted the treasure chest, spiked the door shut from the inside, and spent the night. In the morning there was a loud buzzing coming from outside the door, which turned out to be stirges which were feeding on the corpses they had left outside the door the night before. (The stirges were a wandering encounter; I figured feasting on corpses made the most sense given the circumstances.)

DELVE FOUR

The PC who had been mapping in the previous delve sold their maps to a newly formed adventuring party for a percentage of the treasure liberated on their expedition. (The player of the PC who owned the maps couldn’t play that night.)

This group returned to the tunnels and finished exploring this section of the first level. An elf in the party detected the secret door hidden behind some plaster at area 9A, but when they discovered that the inscription on the door read: “KNOW YE THAT BEYOND THIS PORTAL LIES THE DEMESNE OF THANATOS, THE CURSED, HATER OF LIFE, GOD OF DEATH. SEEK NOT TO PASS THIS GATE FOR IT LEADS ONLY TO HIS BOSOM.” They decided that discretion was the better part of valor and left it alone.

But what the party was really here for was to push through the guard outpost on Level 2. Down they went and got into a huge melee with the anubians. (Complicated by a wandering monster encounter that reinforced the guard post.) During the fight, one of the PCs fell down one of the pits depicted on the map… which led to a chamber where a small dragon was hibernating. (This was all according to the map key.)

There was some abrupt panic, but the PCs rallied and actually managed to kill the dragon. (They were very excited about that.) In the pit they found several ancient Thracian artifacts, which they hauled back to town and sold for a tidy profit. (It was at this point that Himbob Jimblejack bought up all the garlic futures in town and set up his monopoly on garlic sales.)

FIRST DESIGN INTERLUDE

Up until this point, things may seem fairly standard. I haven’t really deviated from or supplemented the original dungeon key. But the one key factor to note here is the effect that random encounters have had on the game. Half of the combat encounters have been with randomly generated encounters:

KEYED ENCOUNTERS

- Lizardmen (Area 5)

- Centipedes (Area 4)

- Anubian Guardpost (Area 7)

- Lower Anubian Guardpost (Area 43)

- Dragon (Area 43)

GENERATED ENCOUNTERS

- Minotaurs + Anubian Guards (Delve 2)

- Anubian Guards (Delve 3)

- Anubian Guards in Area 5 (Delve 3)

- Giant Rats (Delve 3)

- Stirges (Delve 3)

At this point, these generated encounters have accomplished three things.

First, they have slowed the pace of the PCs exploring the dungeon. By providing an additional ablative layer, they have prevented the PCs from delving as far into the dungeon as they otherwise would have been able to. This puts a premium on exploration — their knowledge of the deeper complex is hard-earned and, thus, more appreciated. (Of course, this also presumes that there are interesting and cool things to find down there in the first place. Fortunately, the Caverns of Thracia provide that.)

Second, they prevent a “return to save point” mentality. You can’t just leave the dungeon, come back at a later date, and pick up where you left off. Permanently clearing a section of the dungeon is hard work, and it’s not particularly permanent. (There are not guarantees that something won’t wander back in or that deeper denizens won’t extend their guard perimeter.) This provides a drive to “push on a little farther” because they know that they’ll have to fight hard just to get back to where they are now.

Third, they are keeping this section of the dungeon fresh. In many ways, it really is a completely new dungeon crawl every time they go in. But, on the other hand, their preexisting knowledge of the geography of the place is a reward in itself. (“Oh, I know how to get past these guys. There’s a secret passage a couple chambers to the west that we can use to bypass them.”) That this knowledge is valuable to them is proven by the fact that they were willing to pay cold, hard cash for it.

Tomorrow we’ll take a look at the next step in managing your megadungeon…

As I

As I