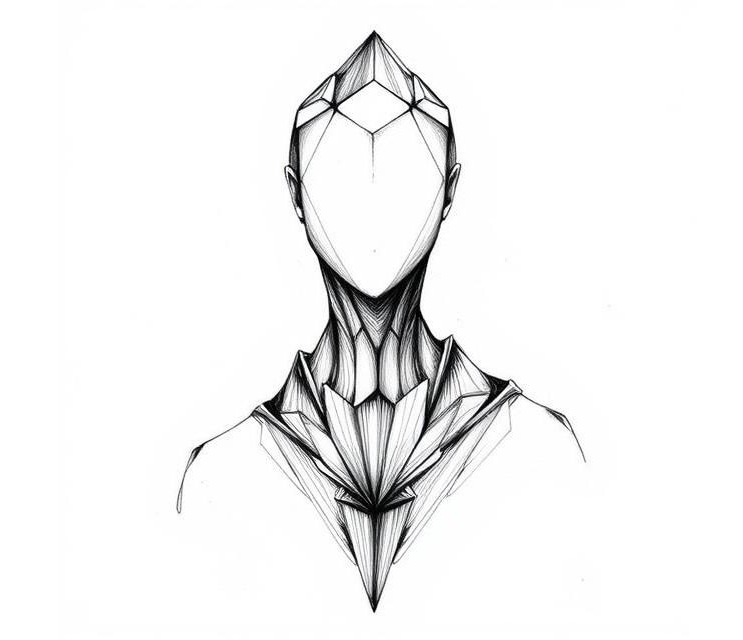

The legendary jewel golems of Shandrala were originally created through the mystic arts of the Jade Magi. Crafted from wondrous stones in great variety, they generally have the appearance of slender humanoids and are possessed of preternatural speed and grace, due to the spirits of air which animate them.

Those destroying these precious creations in the hopes of looting their gemstone bodies will be left disappointed, however: When the spirit of air which animates them escapes their broken bodies, the crystalline structure collapses, leaving behind a fractured form that quickly crumbles to worthless powder.

CONSTRUCTING JEWEL GOLEMS

The first step in the creation of a jewel golem is the selection and enchantment of the birthing gem, from which the golem’s physical body will eventually be crafted. The initial preparation of the birthing gem requires two weeks of work, during which the creator must spend at least 8 hours each day in a specially prepared laboratory or workroom, in which (among other things) a circle of carefully aligned mirrors is used to focus solar and lunar energy into the birthing gem. This chamber is similar to an alchemist’s lab and costs 500 gp to establish. In addition, this preparation consumes 1/10th of the total cost of the golem in question.

Complication: Only the most exceptional of gems are capable of focusing the intense mystic energies that form the heart of a jewel golem. Lesser stones, or flawed stones, will shatter during the preparation process, but only after consuming the preparation cost.

Once the birthing gem has been prepared, the true work of creating the golem can begin. An extensive process of magical rituals, requiring two additional months to complete, must be performed. During this time, the gem is used as a crystalline matrix from which the body of the jewel golem is spontaneously created. In addition, the elemental spirit that powers the golem is gathered and bound to the evolving structure of the golem’s body.

During this period, when not working on the rituals, the creator must rest and can perform no other activities except eating, sleeping, or talking. Interruption of this work for any reason will cause the creator to lose control of the arcane energies they are attempting to harness, destroying the birthing gem and forcing them to start over from scratch if they wish to continue. Note, however, that once the birthing gem is prepared, the creator can wait as long as he likes before using the gem to actually construct the jewel golem. A gem prepared by one person can even be used by another person.

The cost listed for each jewel golem includes all materials and spell components that are consumed or become a part of it.

CONTROLLING JEWEL GOLEMS

There are two types of jewel golems: controlled and free.

A jewel golem’s creator can command a controlled golem if it is within 60 feet and can see and hear its creator. If uncommanded, a controlled golem usually follows its last instruction to the best of its ability, though if attacked it will respond appropriately. The creator can give the golem a simple program to govern its actions in their absence, such as “Remain in this area and attack all creatures that enter” (or only a specific type of creature), “Ring a gong and attack”, or the like. However, jewel golems are generally more intelligent than traditional golems, allowing them to carry out more complex tasks.

A jewel golem can become free in one of two ways.

First, if a jewel golem without an active command is separated from their master for a year and a day, it will automatically become free and capable of pursuing its own goals.

Second, a jewel golem following an active command can, once per year, attempt an Intelligence check against a DC equal to 5 + their creator’s level. On a success, they become free.

There are exceptions to these general guidelines:

- Aquamarine and opal golems are never controlled. They begin their existence as free golems.

- Diamond and pearl golems are always considered controlled, unless their master specifically gives them freedom.

- Moonstone golems are constantly contesting their control. They make an Intelligence check at the moment of their creation and every year thereafter until they are successfully free. (It’s rumored that certain “free” moonstone golems are still controlled by some greater imperative.)

- Bloodstone golems will obey the commands of anyone associated with the holy site they’re responsible for guarding. They can only become free golems if the holy site is completely destroyed, at which point they can attempt an Intelligence check for their freedom. On a failure, they continue guarding the place where the holy site once stood. (Dark bloodstone golems, however, follow the normal rules for controlling jewel golems.)

JEWEL GOLEMS

Pearl Golems

This material covered under the Open Game License.