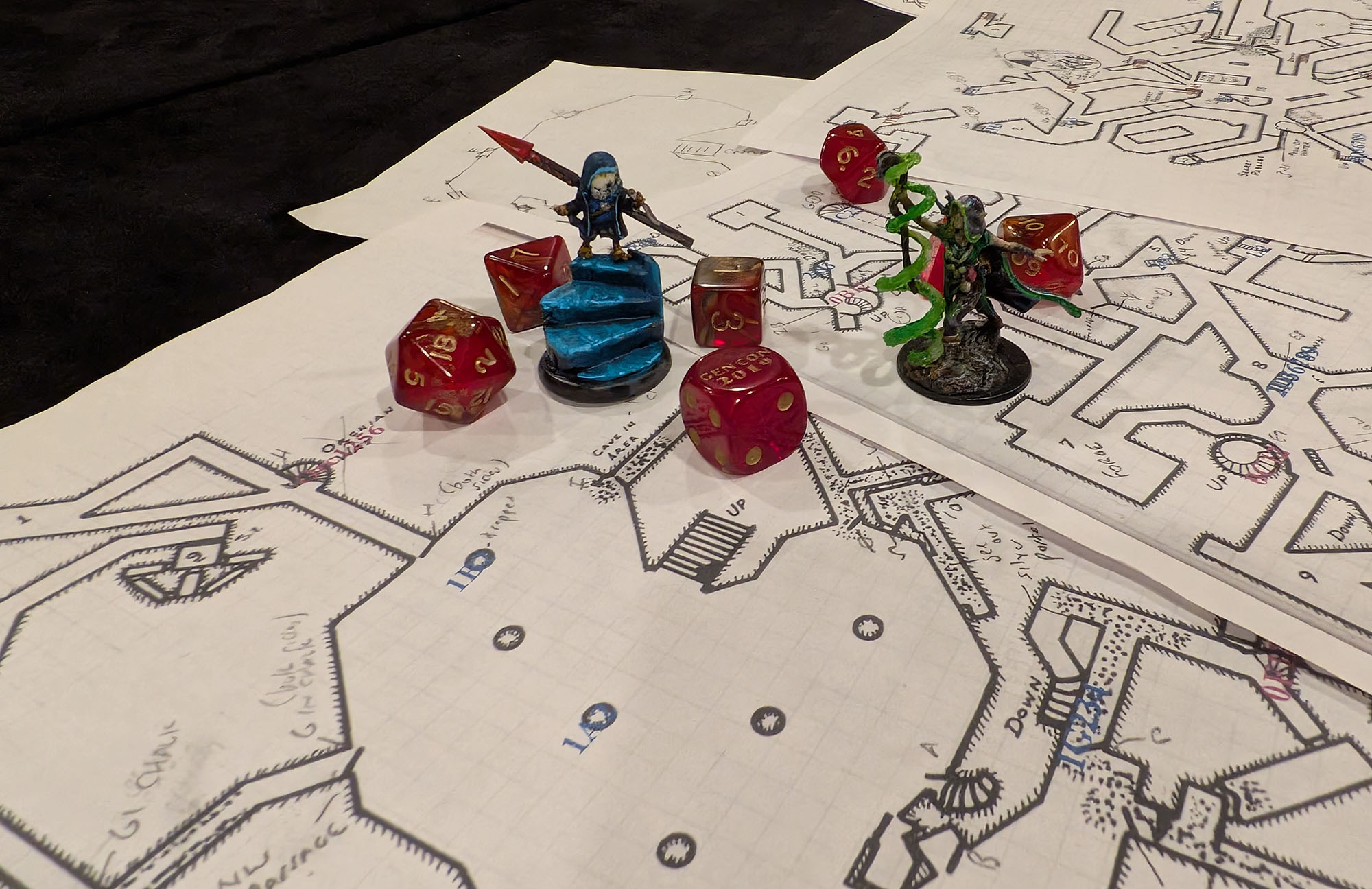

From 2018 to 2020, I ran an open table set in the dungeons of Castle Blackmoor.

If you’re not familiar with Blackmoor, it’s THE original D&D dungeon. Created by Dave Arneson in the early ‘70s, the very first people to ever play a modern roleplaying game crawled through its tunnels. When Arneson took the game to Lake Geneva and ran it for Gary Gygax, these were the rooms that Gygax’s character hacked and slashed his way through.

In 1977, Judges Guild published Arneson’s The First Fantasy Campaign. Although deliberately incomplete (because Arneson wanted to keep secrets from the people still playing in his campaign) and often frustratingly impenetrable (because Arneson sort of just gave Judges Guild a stack of various notes, drawn from multiple periods of time and with little indication of their context, intent, or even relation to each other), this slim tome provides a unique and irreplaceable insight into the early days of the RPG hobby and the campaign that gave birth to D&D.

In particular, as detailed in my Running Castle Blackmoor series, The First Fantasy Campaign includes a copy of Arneson’s dungeon maps and enough information that you can cobble together something resembling his original stocking procedures. Using this knowledge, I reset the clock on Blackmoor (so that my players would be the first to journey within), stocked the Blackmoor maps to create my own version of the dungeon, and launched a campaign that would, ultimately, last for several dozen sessions.

By the time the campaign came to an end, a little over two dozen players had delved into the Blackmoor dungeons. They’d even begun transforming the village of Blackmoor to suit their desires. (More on that momentarily.) COVID was the primary reason the campaign floundered, but there were also some deeper issues with how the campaign was set up. If not for the pandemic, I might have found the time and effort necessary to correct those issues, but unfortunately that never happened.

Nevertheless, I thought it might be useful to review the lessons I learned from running a Blackmoor campaign – both positive and negative. Some of these may be most useful if you’re interested in setting up your own Blackmoor campaign (which I heartily recommend!), but there are quite a few secrets to be gleaned that could be useful for almost any table.

SPECIAL INTEREST XP

In The First Fantasy Campaign, Arneson also describes an experience system based on “special interests.” Instead of earning XP through combat or simple looting, the PCs would instead need to spend money specifically on their special interests in order to advance.

Unfortunately, the system described by Arneson doesn’t work. (I mean this in the most literal sense: There’s missing and contradictory information that makes it impossible to use as written.) I was fascinated by the potential of the concept, however, and designed my own Special Interest XP System to use in my Blackmoor campaign:

- Special interests included carousing, song/fame, religion/spirituality, philanthropy, caranvale, hoarding, training, and hobbies.

- When creating characters, players would randomly determine which special interests would be favored by their character.

- GP spent on a special interest would translate to XP, modified by the character’s level of interest in that special interest.

- Additional rules limited expenditures by the size/quality of a community, providing motivation for PCs to either (a) pursue multiple special interests, (b) travel, (c) improve their community, and/or (d) avail themselves of trade caravans (which served as an additional font of adventure hooks).

Using Special Interest XP: Implementing (and explaining) this system did increase the amount of time required for character creation. For an open table you really want character creation to be as fast as possible, and there were a few sessions where this extra load had a slightly negative effect. It just took too long to start playing.

The solution I found was to delay explaining how the various special interests actually worked until the end of the session. This:

- Reduced the time spent at the beginning of the session.

- Engaged players when they were most excited about the system (e.g., they had money they could spend to earn XP), increasing their attention and interest.

- No longer kept existing players waiting. Since they already knew how the system worked, they could immediately begin plotting how to invest their loot at the end of the session while the new players got onboarded.

I also experimented with pushing the generation of special interests to the end of the session for new players, but this backfired because:

- Players already familiar with the system who were generating new characters wanted to immediately generate their special interests, often creating confusion.

- It created too much bookkeeping at the end of the session when people often needed to wrap things up and head home.

Effects of Special Interest XP: Tweaking the presentation of special interest XP to make it work smoothly at my open table was well worth the effort because the actual effect of using special interest XP in play was astounding.

Let’s talk about PCs investing in their community – buying houses, founding businesses, establishing strongholds, etc. My typical experience with D&D across many different editions is that, unless the DM specifically frames up an opportunity (e.g., an NPC giving the PCs Trollskull Manor as a quest reward in Dragon Heist), it usually takes somewhere between seven and twelve levels before the PCs start setting down roots like this. In practical terms, it requires not only a certain amount of money, but also for the players to have bought all the other goodies (armor, equipment, etc.) they desire.

Special interest XP, on the other hand, saw the PCs immediately start investing in the local community. Within just a couple sessions, a cleric had built a healing chapel on a hill just outside of town. He only had a limited number of healing spells, but even when he wasn’t playing other PCs could visit his character at the chapel and pay for healing.

Other characters established a meadery, erected an elven tree shrine, took over the local church, bought a house, and all manner of things. When one group found a flying machine, they decided that they should donate it to the Steward and his Council, who then charged them with conveying it to the capital of the Great Kingdom as tribute.

To be clear, this was all happening with characters who were below 5th level. I’ve run a lot of D&D over the years and, as I say, I’ve never seen anything like this. If you’re interested in exploring this sort of thing in your own campaign, I definitely recommend adapting Special Interest XP to your system of choice.

STOCKING ISSUES

Almost certainly the biggest problem I had with the campaign was stocking the dungeon.

First, Arneson’s stocking procedures simply didn’t generate enough treasure. (This was even more true when it came to restocking.) Since GP = XP, this meant that the PCs were stunted in their leveling. The lack of leveling also meant that the PCs couldn’t penetrate into the lower levels of the dungeon, which exacerbated the problem.

At a certain point, the PCs were just kind of stuck wandering through rooms that had been thoroughly picked over. Obviously not ideal.

I began experimenting with different solutions, but hadn’t found a completely satisfactory solution before the campaign ended. Therefore, I’d suggest going big for your own Blackmoor:

- Double the amount of treasure in your initial stocking.

- For restocking, double both the likelihood of a new treasure and the value of that treasure.

You should be able to dial it in from there.

(I will note that this might be less of a problem if you’re running Blackmoor as a dedicated table instead of an open one.)

Exacerbating this issue is that the first level of the Blackmoor dungeons is rather small, the second level is only of moderate size, and then difficulty leaps up substantially if you go down to the third level.

Related to this is the lack of variety on the stocking tables. Taken directly from Arneson’s manuscript, for example, the list of possible creatures on the top two levels of the dungeon are:

Orcs, Elves, Dwarves, Gnomes, Kobolds, Goblins, Elves, Fairies, Sprites, Pixies, Hobbits

Not only is the list limited, but it also contains some problematic elements in the Pixies, which appear in large numbers and, according to the 1974 D&D rules, “are able to attack while remaining generally invisible. They can be seen clearly only when a spell to make them visible is employed.” Low-level characters wisely learned to simply flee whenever they encountered a pixie.

These problems only became more pronounced with some of the foes encountered on lower levels. As a result, the dungeon slowly became overwhelmed by impossible foes, further limiting where the PCs could safely explore.

Finally, partly as a consequence of all this, there just wasn’t enough of the cool stuff that Blackmoor offers: The ghosts, weird items, spell eggs, Arnesonian machines, etc.

Some of these problems could have been mitigated if the PCs were leveling up (with more powerful PCs clearing out problem spots and leading expeditions into the lower levels), but it was clear to me that all of the stocking and restocking procedures needed an overhaul if the campaign were going to perform to its best potential.

I love the idea of special interest XP, but there is one problem I can’t figure out. Investing in the town can lead to passive income, which can be re-invested, and before you know it the players are more incentivised to play innkeeper than to dungeon crawl. I imagined a rule where only wealth found via adventure could be spent for XP, but this creates accounting overhead to keep track of what counts and what doesn’t. Any suggestions for handling this?

@Clinticus

An idea I had was based on some thoughts after reading this excellent article: https://acoup.blog/2025/01/03/collections-coinage-and-the-tyranny-of-fantasy-gold/ I’ve been thinking how to work in the idea of economies that are not based on cash into a game. Not because historical accuracy is paramount but because, as the article mentions, it can work really well into the gameplay loop of a typical fantasy adventure to have a town whose economy runs on favors, prestige, and titles.

In this case, you could say that the town does not deal in coinage, but that treasure extracted from the dungeon can nonetheless be sent abroad in exchange for labor and materials that the town otherwise doesn’t have. The town doesn’t want your gold coins and silver chandeliers, per se, but send that stuff to the big city to buy the town a quality anvil, or hire workers to build a tavern, and now the town is in your debt and your prestige (XP) rises. Meanwhile your smithy and inn are not earning you cash, so you’re not thinking of retiring from adventuring. Rather they are earning you favors in town in turn–you can alleviate yourself of the services you have installed in town, as well as pretty much any others because everyone owes you. And the degree to which the town owes you, the degree to which they see you as its benefactor, is already measured–by your XP, which now has a tangible in-game meaning in addition to giving you mechanical benefits.

Oddly enough, I kind of did the “special interest XP” by accident in one campaign, by giving the PCs more money than they could reasonably spend. They responded by building their own town, and the resulting campaign was easily one of my favorites.

I love the idea of a dungeon slowly becoming overwhelmed with impossible foes! It feels like a really interesting emergent property of the game, and also presumably creates a dungeon that characters who reach very high level could go back to.

I just stumbled across this article (https://boggswood.blogspot.com/2023/02/arnesons-early-thoughts-on-od.html), which suggests that maybe the restocking problems you encountered would not have been a huge surprise to Arneson. He wrote:

“Now Blackmoor was not set up as a totally random Dungeon originally but with a overall plan and scheme in mind, not just a meatgrinder for adventurers. This gets me a lot of complaints about lack of action and no treasure (everyone keeps going to the same rooms and I refuse refill them to please them).”

Boggs’ analysis, often very insightful, in that post is way off. He’s quoting Arneson saying “X” and saying, “From this we can conclude not-X.” In other places he’s just making stuff up and claiming Arneson said it.

In this specific case, I’m not just talking about restocking. I’m also talking about the original stocking of the dungeon. The procedures outlined by Arneson in The First Fantasy Campaign simply do not generate enough XP to allow the PCs to continue exploring the dungeon. It’s very likely that he never actually used these procedures, or modified the outcomes so extensively that they were merely suggestions.