THE DUNGEONS

Call of the Netherdeep is studded with a sequence of really cool dungeons:

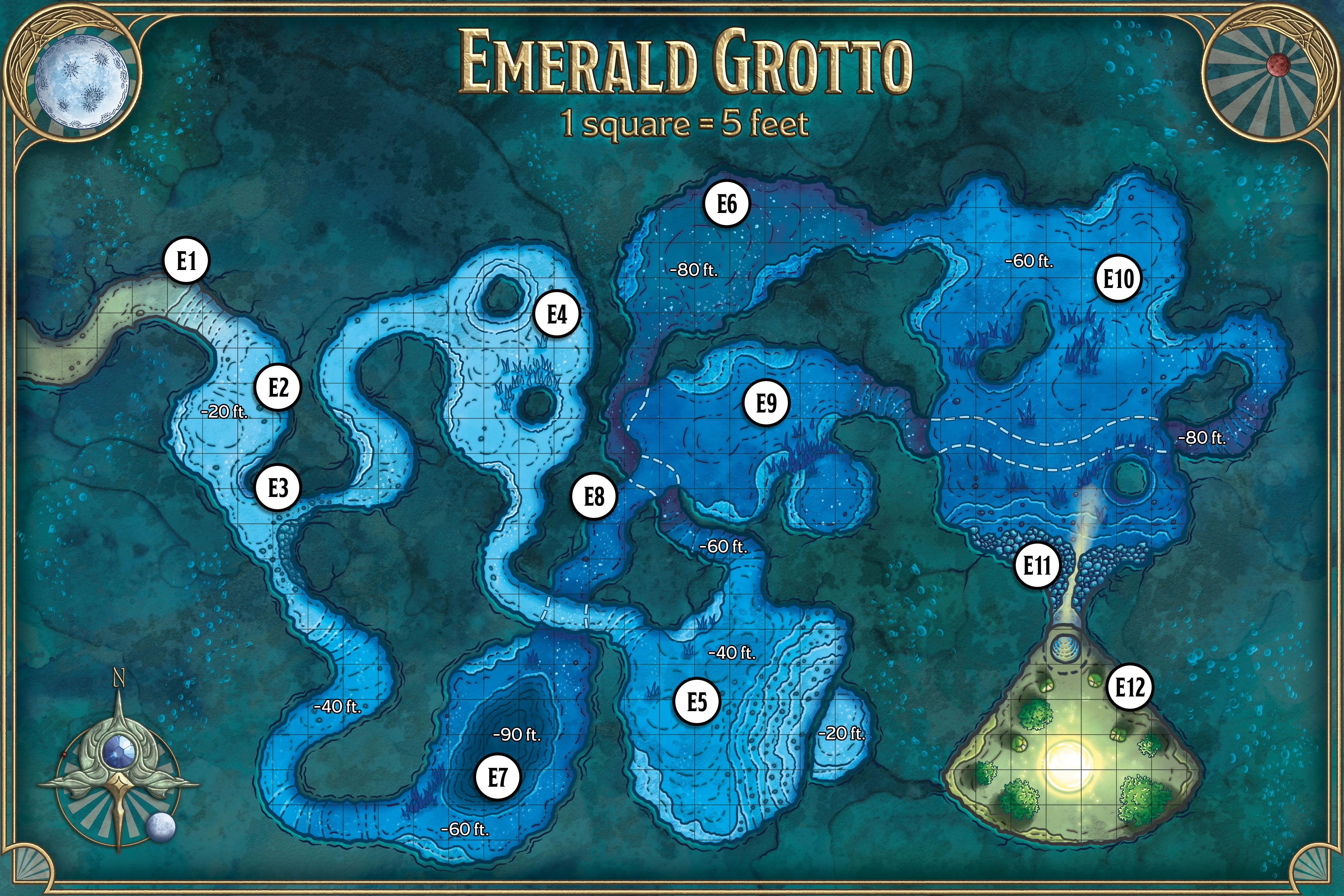

- Emerald Grotto

- Betrayers’ Rise

- Cael Morrow

- The Netherdeep

Emerald Grotto is the launch point of the campaign. It’s a pretty basic cave design, but the underwater setting gives it some nice flavor. The forked design is also used to structurally highlight the relationship between the PCs and the Rivals.

Betrayers’ Rise is you standard “cyst of evil” affair, but the devil is in the details here. (Pun intended.) The map is lightly xandered, giving the PCs some nice strategic control in their exploration, and the key is drenched in gothic atmosphere.

Cael Morrow is a sunken city. Or, more accurately, a small part of this city. This is probably the weakest of the dungeons, but is still quite good. The back half opens up, allowing for a more freeform exploration of the ruins, and the key is once again excellent in its specific detail.

The Netherdeep is the big finale of the campaign, an extrusion of the Apotheon’s subconscious mind and memory. And, not to sound like a broken record, once again the map is great and the key richly detailed.

Here’s a good example of how great these dungeon keys are:

R2. HALL OF HOLES

The walls of this hallway are covered with carvings that depict a great battle involving mortals, celestials, and fiends. A faint whistling noise emerges from the walls, sounding almost like snoring.

A character who succeeds on a DC 15 Intelligence (History) check recognizes the wall carvings depict the Battle of the Barbed Fields. This fight was a climactic battle of the Calamity, in which the devotees of the Prime Deities broke through the garrison at the Betrayers’ Rise and reached the walls of Ghor Dranas. Prominently depicted in one scene is a proud, melancholy warrior with curly hair carrying a spear and shield. By his side are two figures; a white-haired girl no more than twelve years old, and a young adult woman with hair that flows behind her, turning into a road upon which countless soldiers march. A character who makes a successful DC 10 Intelligence (Religion) check realizes that the latter two are common depictions of the gods Sehanine the Moon Weaver and Avandra the Change Bringer.

There are several things to note here.

First, the boxed text invokes multiple senses, not just sight.

Second, you see generic “there are pretty pictures on the wall” or “there are some statues here” in dungeon keys all the time, but the writer here has taken the effort to get specific with the art: The hall isn’t just covered in carvings; it’s covered in these specific carvings depicting this specific thing.

Third, this effect is enhanced with multiple skill checks allowing one or more PCs to dive even deeper into the lore. This turns the lore into a reward, giving real meaning to the PCs’ abilities and also likely investing the players more deeply in what their abilities have revealed.

In a single room, this attention to detail is nice. Over the course of the entire campaign, it elevates the entire experience. This is the practical method by which the world of Exandria is brought to vivid life in Call of the Netherdeep.

When it comes to the dungeons, however, I do have a quibble.

Taken on their own merits, Betrayers’ Rise and Cael Morrow are both really good dungeons. The problem is that the dungeons are too small for the lore surrounding them.

Betrayers’ Rise, for example, is presented as a sort of Moria or Undermountain: A vast underground complex with depths unexplored and perhaps unexplorable, out of which demons of the Abyss emerge to threaten the town above. But the actual dungeon found in Call of Netherdeep is teeny-tiny, consisting of just sixteen rooms.

To address the mismatch, the writers kind of toss out the idea that “the characters experience a particular version” of Betrayers’ Rise, and that others experience “different configurations” of the dungeon. They also provide “Betrayers’ Rise Encounters” (p. 63) that can be used as inspiration to “expand” the Rise. But ultimately you’re selling one experience and then delivering another.

Betrayers’ Rise does, ultimately, work as presented, even if it’s not ideal. More problematic is Cael Morrow: Here again, the lore treats the drowned city as a vast archaeological site… but only delivers a handful of buildings and seventeen keyed locations.

In Cael Morrow, however, this is not just an aesthetic mismatch; it’s a deeply flawed structure. The campaign is designed with the expectation that the PCs will journey down into Cael Morrow for a series of faction missions (at least three, possibly more). This makes sense if the archaeological expedition is exploring the entirety of the ruined city, but it isn’t. Cael Morrow simply isn’t large enough to support the iterative missions.

Imagine that you give the PCs a faction mission that sends them into a dungeon. And, when that mission is done, there are seven DAYS until they receive their next mission. (And then another seven days between that mission and the one after that.)

What are the PCs going to do?

Well, if they didn’t completely explore the dungeon during the first mission (and they very easily may have), they’re almost certainly going to go back and finish exploring the dungeon.

Again: It’s only seventeen rooms.

And there’s nothing else for them to do in Ank’Harel.

Because Cael Morrow’s design doesn’t match its lore, there’s just no way these faction missions can work as written.

A good chunk of Cael Morrow is also hilariously linear given the nature of these missions.

The way it works is that the Allegiance of Allsight (one of the Ank’Harel factions) has used magical keystones to create regions of the city where the water is held back, making it much easier for them to excavate these sites. In practice, what they’ve done is create a linear corridor of air about 300 feet long.

One of the Allsight faction missions involves the primary archivist, who is concerned because one of his researchers has been missing for three days and he has no idea where she might be.

Where is she?

200 feet away, straight down a linear corridor.

To be clear, the problem here is not that the excavation site is limited to only one small portion of the city. (As I mentioned before, on its own merits the design of Cael Morrow dungeon is pretty good.)

The problem is that everything in the campaign — the NPCs, the faction missions, the lore, the pacing — is pretending this isn’t the case.