In (Re-)Running the Megadungeon, we looked at how you can evolve a megadungeon over time, actively playing it just like the players actively play their characters: You repopulate it. You modify it. You roleplay the inhabitants.

In the process, you create a dynamic experience that’s constantly surprising and delighting (and terrifying) your players, while also dramatically extending the amount of high-quality playing time you can get out of surprisingly simple prep.

Now I want to return to the series, flip things around, and take a closer look at how the players can evolve the megadungeon over time.

(If you’re here because you’ve innocently just started reading the series: Alert! The last link skipped you forward in time by a dozen years! Don’t worry! Any resulting temporal anomalies will resolve themselves shortly without disrupting your personal continuity.)

INTO CASTLE BLACKMOOR

Of course, almost any action the PCs take in a megadungeon will affect its future form. This is, after all, a back-and-forth dynamic. Killing all the lizardmen is what allows the elementalist to move in and set up shop, right? But what I want to spotlight today are the cases where the PCs more deliberately (and proactively) transform the dungeon.

Most of the examples we’ll be looking at here come from the open table campaign I ran in Castle Blackmoor, the original megadungeon created by Dave Arenson in which the modern roleplaying game was invented, and from which modern D&D was born. Running Castle Blackmoor provides a deeper look into how I set up and ran the campaign, but all you really need to know for now is that Castle Blackmoor sits atop a hill and beneath it lies the dungeon.

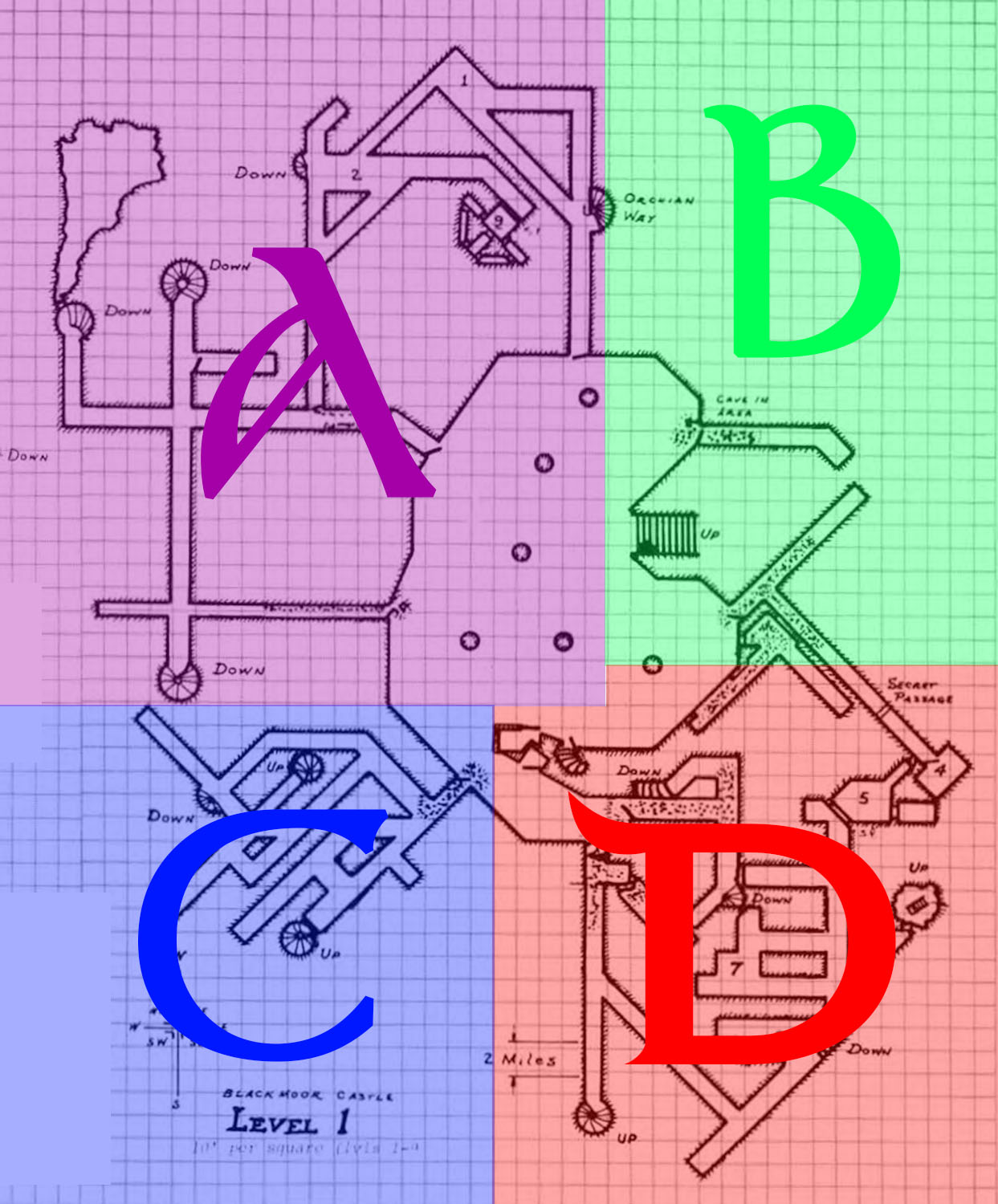

When the PCs enter the dungeon, this is the first room they encounter:

Speaking frankly and from experience, this room is incredible.

First, it’s too large for normal torchlight to fully illuminate it. So you’re immediately thrown into a fog of war.

Second, even if you have a more powerful light source, the shape of the room means that you can never see the entire room when you first enter it, no matter which entrance you use. Whether you’re entering the dungeon for the first time or returning to this chamber in the hopes of escaping to the daylight above, you can never be entirely certain if the room is empty… or if there’s something lurking just around the corner.

Third, and most importantly, there are ten doors. (Plus three more secret doors, including two hidden in the columns that aren’t indicated on the map here.) Literally the moment a PC steps into the Blackmoor dungeon, the player is confronted by the absolute necessity to make a choice: Which door are we going to open? Where is our adventure going to take us? The DM isn’t going to make that decision for you. You’re in control of what happens here.

Even if you have literally never played a roleplaying game before (and I’ve run Blackmoor for such players), this room inherently pushes them into actively engaging with the scenario while simultaneously teaching them that the game is about the choices they make.

The entire room screams player agency, and then holds forth the promise of endlessly varied adventure (every time you come back, you can pick another door). It tells you literally everything you need to know about Blackmoor, about dungeons, and about the game in an instant and without ever explicitly explaining any of it.

Playtest Tip: Describing the shape of this room verbally is impossible. If you’re playing in the theater of the mind, nevertheless make a rough sketch of its shape and be prepared to show it to the players. I kept a copy of the sketch I made clipped to my Blackmoor maps. But I digress.

The reason I bring it up here is that it’s a really simple example of player transformation of the dungeon: Confronted with all those doors, the players were confusing themselves when discussing their options and making their maps. So for the sake of clarity, they labeled the doors: First on the maps and then, shortly thereafter, in the dungeon itself.

Starting with the door to the left of the staircase, they labeled them alphabetically, A thru J. (Hilariously, however, the group who first did this missed one of the doors, so “J” ended up out of sequence.) The doors were first labeled in chalk (which one of the PCs had purchased), and this was later made more permanent when mischievous sprites in the dungeon started erasing the labels.

In doing this, my players were unwittingly echoing what Dave Arneson’s original players had done nearly fifty years earlier: After arbitrarily choosing the northwest door, they apparently fell into the habit of using it to mount most of their expeditions. It became known as the “Northwest Passage,” and eventually one of the players hung a wooden placard over the door with this name written upon it.

In my game, a later group took this even further, making coded markings at the various stairs in the dungeon to serve as navigational aids. These codes actually referred back to the door names (so for example, a staircase labeled G2 indicated that they were on the second level and this staircase would take them back to Door G… assuming that they hadn’t gotten lost or confused and encoded the wrong information).

TANGLEFUCK

Becoming lost and confused reminds me of another fun story from my Blackmoor table.

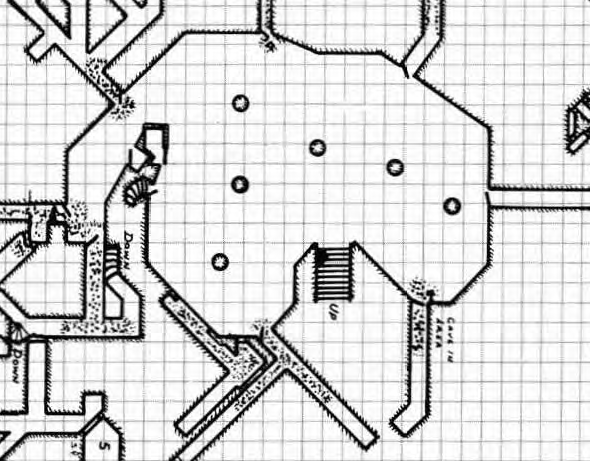

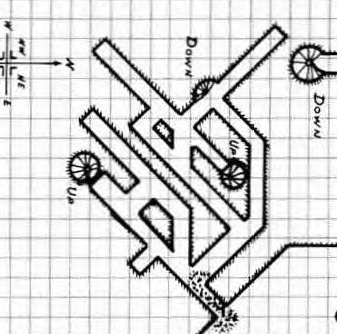

Looking at this section of the dungeon on the map, it seems fairly straightforward, although you may note Arneson’s devilish penchant for oddly angled diagonals.

One evening, however, a group headed into this section of the dungeon and began going in loops. Their map rapidly metastasized (because they were mapping the same corridors over and over again as if they were new passages), and by the time they realized what was happening they were hopelessly disoriented. They began making navigational marks (labeling walls and intersections), but because they were already lost, most of these marks were incorrect, contradicted each other, and only added to their confusion.

Fortunately, everyone at the table was having a great time with this, laughing uproariously whenever the PCs circled around, confident they were breaking new ground, only to come face-to-face with their writing on the wall or floor. (At this point, the sprites had already begun messing with the door labels, so there was also paranoia that something was here in the hallways with them and was altering their signs.)

One memorable moment came when they arrived at an intersection, confidently declared that they had gone left the last time they were here, so they were going to go right this time and they would definitely get out! … except that wasn’t right, and so they ended up looping back around and coming back to the same intersection again.

“Okay, so we definitely went left last time, so we need to go right this time.”

They did this four times!

Ironically, the door out was, in fact, immediately to the left of that intersection.

When they finally figured this out and, with great relief, headed through the door, one of the PCs stopped, took out some charcoal, and wrote in large dwarven runes on the wall, as a warning to all who might come here in the future: TANGLEFUCK.

And thus this section of the dungeon came to be known forever after.

OTHER TALES FROM THE TABLE

In another campaign I ran, the PCs began collapsing tunnels to prevent anyone else from entering a section of the dungeon haunted by a malevolent force. In yet another, the PCs memorably hired a group of mercenaries to guard the entrance to the dungeon and prevent other adventurers from entering. (An effort which met with mixed success.)

These player-led transformations are particularly wonderful in an open table: Because there are other players exploring the world who were not part of the group which made the original changes, those players get to discover them as artifacts of the world (and, conversely, leave their own transformations for others to discover in turn).

These long-term interactions across multiple sessions and groups can pay off in a multitude of gloriously unexpected ways. For example, I mentioned that my Blackmoor players began encoding navigational markers. But there were actually multiple characters who had the same idea, which meant that different groups were encoding information in different, overlapping ways. And then there was the memorable group where only one player had previously been part of an encoding group… and he screwed up the code. So not only did that group leave miscoded marks, but the other PCs in the group — who had been taught the incorrect method — carried that mistaken information into other groups and spread it even farther.

So who made these markings? Another group of explorers? Or monsters looking to trick the interlopers?

The fact that there are other real people interacting with this shared game world and that you can see the consequences of their actions and they can see the consequences of yours is intoxicating. (And can easily lead to motivating players to make even larger and more meaningful impacts on the game world.)

Even at a dedicated table, however, player-led transformations are great. It’s basically GMing on easy mode: You can often just lean back and take notes.

More importantly, the players are metaphorically throwing you a ball. They’re inviting you to play with them, and in the process making it a lot easier for you to generate your own responses that will continue to evolve the dungeon. (Like those sprites altering the navigational markings.)

All you need to do is pick up the ball and throw it back.

FURTHER READING

Treasure Maps & The Unknown: Goals in the Megadungeon

Keep on the Borderlands: Factions in the Dungeon

Xandering the Dungeon

Gamemastery 101