A subject somewhat related to hidden vs. open difficulty numbers is the matter of open and hidden stakes. In other words, whether or not the players know why they’re rolling the dice.

In most cases, of course, the stakes are known: If you’re trying to jump over a crevasse, the dice roll is determining whether you do so or not. But there are action checks where that isn’t necessarily true: If the GM calls for a Perception test while the PCs are traveling through a jungle, the players don’t necessarily know if it’s to notice a tribesman lying in ambush, a hidden treasure, a treacherous piece of terrain, or something else entirely.

Perception tests are, in fact, probably the most common form of this. (Since they literally determine whether or not you’re aware of something.) But the principle can be applied to other tests and reactive mechanics, too. Calling for a saving throw against undetected dangers or unknown spells before explaining what the consequence of a failure will be is a great way to ratchet up the anxiety at the table (particularly if it’s the exception rather than the rule).

I’ll sometimes do the same thing with Sanity checks in Call of Cthulhu, Stability tests in Trail of Cthulhu, and similar mechanics: Call for the check (the magnitude of which in Trail of Cthulhu can foreshadow just how bad things are about to get) and then describe the eldritch horror, allowing the players to immediately respond according to whether or not (or how badly) their character failed the test.

(Enabling this immediate, immersive response to narration by preemptively resolving a mechanical component which might normally follow the narration is why I also roll initiative at the end of each encounter and keep it stored for future use.)

One potential pitfall of such checks, however, is that you’re unable to take advantage of a player’s familiarity with their own character: If you’re asking them to make a saving throw vs. fireball, it’s much more likely that you’ll forget that they have a +2 bonus to saving throws involving fire than it is that they will. And if you do forget, then the subsequent revelation can deflate as the mechanical resolution needs to be revisited.

ROLLING MEANINGLESS DICE

The existence of hidden stakes also opens the opportunity for another technique: Rolling meaningless dice.

This generally falls into two categories. First, rolling dice behind the screen for the sound effect. That can be valuable as a tool of misdirection, but it’s not primarily what we’re talking about here.

Second, having the players roll for checks that don’t mean anything.

Now, we’ve already established that dice should only be rolled if the potential failure state is interesting, meaningful or both. And if it is neither, you shouldn’t roll the dice. If that’s the case, it would seem to follow that you should never have people rolling meaningless dice.

But here’s the exception: You only roll if failure is meaningful or interesting… but sometimes you’ll roll the dice because the character believes failure could be meaningful or interesting and saying that dice will not be rolled will reveal information that the character does not have.

Searching for a trap that isn’t there is an obvious example of this.

Paradoxically, the reason you roll the meaningless dice generally isn’t to the benefit of the meaningful roll; it’s to enhance the meaningful rolls of the same type. For example, there’s seemingly no harm in cutting to the chase with exchanges like:

Player: I search the hallway for traps.

GM: There are no traps in the hallway.

It even seems to follow logically from the principles we’ve established. The GM is defaulting to yes (the “yes” in this case being “yes, your search of the hall is successful in determining there are no traps”; don’t be fooled by the presence of the word “no” in what the GM said). But if do that a dozen times and then have this interaction:

Player: I search the hallway for traps.

GM: Okay, make a Search test.

The player automatically knows there’s a trap in that hall before they even pick up their dice. The GM’s pattern of behavior has revealed metagame knowledge that puts the player in the position of knowing something that their character does not.

And sometimes metagame knowledge is unavoidable (but in this case, it’s unnecessary). And sometimes that’s desirable (but in this case, there’s nothing being gained). And some players believe it won’t make any difference (but for someone who values immersion, it will). In my experience, nothing ever seems to be gained from this interaction and almost always there is something lost, so I recommend rolling the meaningless dice and preempting the loss.

USING MEANINGLESS DICE TO EFFECT

In some cases, you can deliberately use this effect reactively.

For example, as I’ve discussed previously in Metagame Special Effects, I not infrequently call for Perception checks even when there’s nothing to perceive. In addition to camouflaging which Perception check failures are important and which aren’t, this can also be an effective technique for heightening paranoia at the table.

The biggest reason I do it, though, is that I’ve found it’s the single most effective way to refocus the table’s attention on the game world when extraneous distractions and chitchat have derailed the players. (You’d think that just saying, “Okay, let’s focus.” would be equally effective, but I’ve found that it isn’t. Ask people to focus in a kind of general way and they engage in a “focusing process”. Ask them to do something specific and concrete, on the other hand, and they become immediately focused.)

Eventually, of course, all of my players eventually figure out that I’m frequently “crying wolf” with these checks. But it doesn’t matter: The more experienced heroes may no longer be quite so skittish or paranoid as they jump at imaginary shadows, but the tool still works.

And, of course, in a dangerous universe filled with wandering encounters, some of the Perception tests you use to refocus the table won’t be meaningless at all.

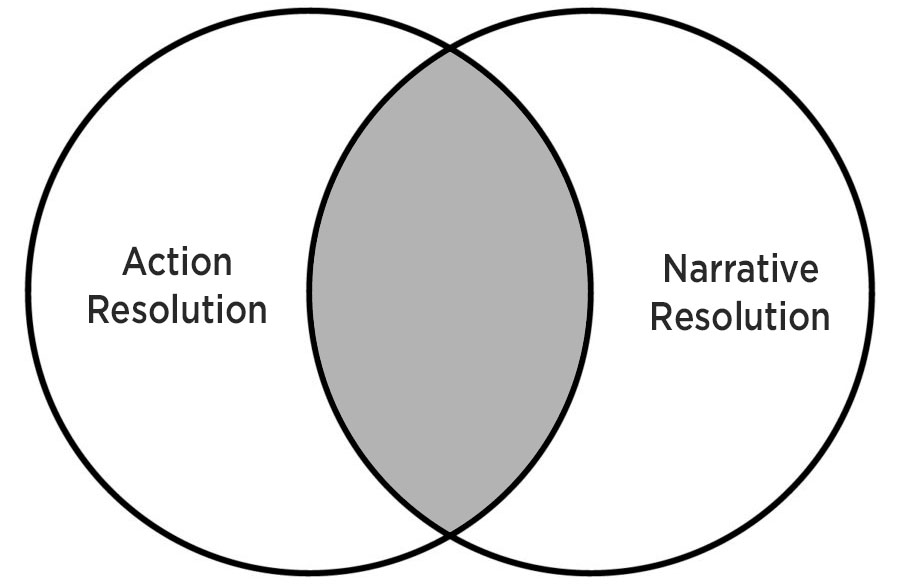

As a result of long tradition, most mechanical resolution in roleplaying games takes the form of action resolution. There is, however, an alternative paradigm that you may find useful: narrative resolution.

As a result of long tradition, most mechanical resolution in roleplaying games takes the form of action resolution. There is, however, an alternative paradigm that you may find useful: narrative resolution.

Now that we’ve discussed the totality of making a ruling from beginning to end, I want to discuss a handful of advanced techniques – various tips and tricks I’ve picked up or created over the years.

Now that we’ve discussed the totality of making a ruling from beginning to end, I want to discuss a handful of advanced techniques – various tips and tricks I’ve picked up or created over the years.