Go to Part 1

Another resolution convention which GMs habitually fall into without really consciously thinking about it is the belief that every action needs to be resolved in a single check.

This is not universally true, of course. Combat is an obvious counterexample. And, indeed, it’s often intuitively understood that actions taken in the physical realm should be broken down into discrete steps: You can’t walk through a locked door until you figure out how to open it. If you want to shoot a rocket launcher from a sniper perch at the top of a cliff, you first have to climb the cliff.

These techniques, however, can be fruitfully applied in a much wider capacity. When we fail to recognize that, we end up robbing our gaming experiences of the depth they could possess. And, in some cases, we end up struggling with action resolutions which should be relatively straightforward to adjudicate.

MULTI-STEP ACTION RESOLUTION

Before we delve into how a multi-step resolution can be designed by the GM, let’s first consider a few ways in which multi-step resolutions can organically arise during play.

The first, and perhaps most straightforward method, is an incomplete declaration of method. To take one of our earlier examples, a player declares that they want to climb to the top of a cliff. That action is resolved. Then they declare that they want to shoot someone from the sniper perch at the top of the cliff. In this case, the player’s intention was always to take their shot from the sniper’s perch, but they broke that intention down into separate chunks. There is an instinctual understanding that X has to happen before Y.

Second, a multi-step resolution can also be the result of a partial success or failure: Your intention is to get to the other side of the chasm, but your Jump check was a partial failure and you ended up clinging to the ledge on the far side. Now you’ll have to take another action in order to complete the intention.

The take-away here is that resolutions which are potentially multi-step can be of a variable length and, in some cases, will even collapse down into a single step. (To invert the example, you might think that someone would need to leap across the crevasse, grab the edge, and then haul themselves up. But then they roll an extraordinary success and that multi-step resolution conflates down to a single leap that carries them all the way across.

Finally, there’s action economy. Multi-step action resolutions often crop up in combat, for example, because there’s a hard limit to how much you can accomplish on any given turn: “I will go here this round so that I can go over there next time.”

Looking at these organic examples, we see that they tend to break down into a pattern of X then Y then Z – i.e., X needs to happen before Y can happen. This is similar to the end of Star Wars: The Force Awakens: The landing party needs to successfully make a hyperspace approach to the planet before they can deactivate the shields, and they need to deactivate the shields before the Resistance can attack with their X-Wings.

Looking at these organic examples, we see that they tend to break down into a pattern of X then Y then Z – i.e., X needs to happen before Y can happen. This is similar to the end of Star Wars: The Force Awakens: The landing party needs to successfully make a hyperspace approach to the planet before they can deactivate the shields, and they need to deactivate the shields before the Resistance can attack with their X-Wings.

But another option is for multiple requirements to be met before you can attempt a subsequent action – X, Y, and Z all need to be accomplished before you can do A. This is, roughly speaking, what happens at the end of Star Wars: The Phantom Menace: Amidala needs to capture the Viceroy, the Jedi need to defeat Darth Maul, and Anakin needs to destroy the droid control ship before the Trade Federation can be forced to negotiate a new treaty.

The other thing to notice is that this can become very fractal: It takes X, Y, and Z to accomplish your goal, but accomplishing X means doing A, B, and C first.

THE PATH OF MEANINGFUL CHOICES

Now, let’s turn our attention away from multi-step resolutions that emerge organically and instead look at how the GM can deliberately choose to resolve an action through multiple steps. When should you do it? Why are you doing it? How many steps do you break the action into?

One way of looking at this is what the Angry DM refers to as a visible benchmark: When you’ve completed one step of the multi-step resolution process, there should be a clear benchmark representing progress towards the goal. For example, imagine a generic scenario in which a PC is picking the lock on a door and the GM decides to resolve it as a sequence of three Lockpicking checks. After the first check has been completed, the GM says, “Do you want to continue picking the lock?”

That’s nonsense. Why is the GM asking that question? It’s meaningless. And you can imagine similarly meaningless interactions: “You’ve convinced him a little more.” “You’ve driven a couple more blocks towards your appointment, do you want to keep driving?” “You continue following the tracks.”

If we look back at our organic examples, we can see how they naturally include visible benchmarks: Once you’ve climbed the cliff, you’re no longer at the bottom of the cliff. After your leap across the chasm comes up short, you are now clinging to the opposite side (giving you different options than you had before). If you attack someone in combat the question could easily be, “Do you want to keep attacking him?” but if you succeed on the attack then you’ve dealt them damage and if your attack failed then you’ve afforded them an additional opportunity to attack you.

Coming back to our meaningless examples, we can also add visible benchmarks to them: For example, you might model picking the lock on a door as requiring three checks in order to determine how long it takes them to get the door open, measuring that against either a hard deadline (there’s a guard coming around the corner) or a fluid one (combat is raging around them and every extra round it takes them to open the door is another round their comrades have to hold off the orcs).

The vast majority of the time, these benchmarks should be visible to the characters, but there may be some instances – like the approaching guard – where the benchmark is meaningful in the game world without the characters (or possibly even the players) being aware of why.

In fact, we can probably generalize this concept of “visible benchmark” to “meaningful consequence”: Each step of a multi-step resolution should have a meaningful consequence. (And it should preferably be meaningful whether the resolution of that step is a success or a failure, for the same reason that this is the gatekeeper for single-step action resolution.) And this often means returning to our familiar friend, the meaningful choice.

In other words, if you look at the totality of an action resolution and you break it apart at each moment in which there is either a meaningful choice or a meaningful consequence… those end up being the individual steps of the multi-step resolution.

VECTORS

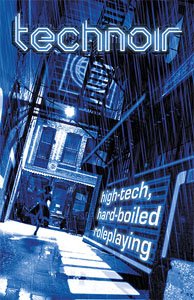

Another way of looking at multi-step action resolution is what Technoir refers to as vectors. To paraphrase from the game, you have a clear vector to your objective when:

- The player’s description of the action is feasible.

- There is a clear path for the action. There are no obstacles the character must surmount first.

- The objective is a logical consequence of the action described.

A vector is, in short, another name for a method, but imbued with the conceptual idea of a straight line: Look at where the vector is being aimed. If it can’t hit what it’s being aimed at (because there’s an obstacle in the way), then you’ll first need to identify a vector which will put you into a position where you can hit what you’re aiming for.

A vector is, in short, another name for a method, but imbued with the conceptual idea of a straight line: Look at where the vector is being aimed. If it can’t hit what it’s being aimed at (because there’s an obstacle in the way), then you’ll first need to identify a vector which will put you into a position where you can hit what you’re aiming for.

This process can be almost absurdly obvious when you apply the thinking to a physical objective. For example:

- You want to go into a room, but the door is shut.

- You want to open the door, but the door is locked.

- You want to pick the lock.

LOCK → DOOR → ROOM

But once you understand the basic concept of vectors, the same logic can be fruitfully applied to more abstract situations. They’re great for modeling social encounters, for example:

- You want to convince the rep from LVC (Lunar Venture Capitalists) to fund your zero-point energy generator, but you need to convince him it’s profitable.

- You want to convince him it’s profitable, but you need to convince him it works first.

- You want to use your scientific presentation to show him it works, but he’s busy and is brushing you off.

- You want to fast talk him into listening to you.

FAST TALK → PRESENTATION → PROFIT → FUNDING

And although these examples have their vectors drawn backwards from the goal (I want to take my shot at X, where can I see X from?), it can be equally useful to draw vectors from the opposite direction (particularly for GMs designing a multi-step resolution). Take a research test to discover information on the Serpent Crowns of Valusia for example:

- A web search doesn’t reveal much, but does tell you that there may be more information in H.L. Menckel’s Beneath the Waves: Arcane Archaeology of the Mediterranean, a rare volume.

- Additional research at the local college library indicates that the only known copy of the book was recently purchased at auction by Johnny Marcone.

- A networking test reveals that Marcone frequents the Velvet Room.

- A seduction roll gets you past the bouncers at the front door.

And so forth.

HOT-SWAPPING VECTORS

One of the major conceptual advantages of this approach is that you can easily hot-swap vectors: Instead of picking the lock, you can seduce the concierge to give you the key. Or pickpocket the master key off the bellhop. Or break the door down.

SEDUCE → DOOR → ROOM

PICKPOCKET → DOOR → ROOM

BREAK → DOOR → ROOM

Alternatively, instead of going through the door, you could climb through the window. Or break through the wall. Or teleport inside.

Of course, this also works great with non-physical vectors: You can get the LVC rep to talk to you by fast talking him. Impressing him with your past accomplishments. Seducing him. Using a display of your zero-point energy device to amaze him.

I find this concept of “hot-swapping” incredibly useful: It allows the GM to construct a framework for resolving complex, multi-step sequences without constraining the options of the players. It keeps your adjudication flexible and loose, allowing player creativity to flow through the structure.

Correctly interpreted, it also shows that the distinction between “organic” multi-step actions and GM determined multi-step actions is, in many ways, a purely arbitrary one. The “organic” examples are simply those where the GM and/or the players instinctively see the vectors involved, whereas the “determined” actions are simply those where they need to think about it. Over time, and with practice, more and more of these interactions are likely to become instinctual and second nature.

BREAKING VECTORS

In general, a vector should terminate at the point from which the next vector is being launched (i.e., the point at which the action changes direction). If you finish resolving a vector and the next vector is pointing in the exact same direction, you’re generally left with one of those meaningless questions we talked about earlier. (“Do you want to keep picking the lock?”)

Partial successes and failures, however, can often be expressed as broken vectors: You were running towards point X, but you slipped and you fell. Or something blindsided you. Or you smashed into an invisible wall (or other obstacle you were unaware of). In some cases, these broken vectors will create obstacles which will force the creation of new vectors to route around them, but in many cases they’ll be transitory delays after which the character can point themselves back in their original direction.

For example, let’s go back to that locked room:

LOCK → DOOR → ROOM

On a partial success, the character picks the lock to the door but is spotted by a security guard. This inserts a new vector, after which they resume their original trajectory:

LOCK → FAST TALK GUARD → DOOR → ROOM

Broken vectors can also be found in situations of endurance. For example, if a character is trying to hold a door shut while a werewolf pounds on it from the other side, they can end up with a vector that looks like this:

HOLD DOOR → HOLD DOOR → HOLD DOOR → HOLD DOOR

Probably repeating the same check over and over again from one round to the next while their friends desperately try to figure out an escape route.

You can see a similar pattern in what I refer to as operatic actions for purely idiosyncratic reasons (because I perceive a pattern in opera music where emotional crescendos are achieved through a series of cyclical builds in the power of the music). I also see this pattern a lot in anime or manga, where a character has to build up power over time and the longer they can sustain that build the more effective the result. (A more mundane example might be convincing members of the jury.)

However, now that we’ve talked about how to break an action resolution down into multiple parts, let’s do the exact opposite…

Go to Part 8