“Most of the campaigns I’ve really enjoyed have been in systems I didn’t like.”

“A great GM can take any RPG and run a good game.”

“I just want a system that gets out of the way when I’m playing.”

What I think these players are discovering is that most RPG systems don’t actually carry a lot of weight, and are largely indistinguishable from each other in terms of the type of weight they carry.

In theory, as we’ve discussed, there’s really nothing an RPG system can do for you that you can’t do without it. There’s no reason that we can’t all sit around a table, talk about what our characters do, and, without any mechanics at all, produce the sort of improvised radio drama which any RPG basically boils down to.

The function of any RPG, therefore, is to provide mechanical structures that will support and enhance specific types of play. (Support takes the form of neutral resolution, efficiency, replicability, consistency, etc.) If you look at the earliest RPGs this can be really clear, because those games were more modular. Since the early ’80s, however, RPGs pretty much all feature some form of universal resolution mechanic, which gives the illusion that all activities are mechanically supported. But in reality, that “support” only provides the most basic function of neutral resolution, while leaving all the meaningful heavy lifting to the GM and the players.

To understand what I mean by that, consider a game which says: “Here are a half dozen fighting-related skills (Melee Weapons, Brawling, Shooting, Dodging, Parrying, Armor Use) and here are some rules for making skill checks.”

If you got into a fight in that game, how would you resolve it?

We’ve all been conditioned to expect a combat system in our RPGs. But what if your RPG didn’t have a combat system? It would be up to the GM and the players to figure out how to use those skills to resolve the fight. They’d be left with the heavy lifting.

And when it comes to the vast majority of RPGs, that’s largely what you have: Skill resolution and a combat system. (Science fiction games tend to pick up a couple of additional systems for hacking, starship combat, and the like. Horror games often have some form of Sanity/Terror mechanic derived from Call of Cthulhu.)

So when it comes to anything other than combat — heists, mercantile trading, exploration, investigation, con artistry, etc. — most RPGs leave you to do the heavy lifting again: Here are some skills. Figure it out.

Furthermore, from a utilitarian point of view, these resolution+combat systems are all largely interchangeable in terms of the gameplay they’re supporting. They’re all carrying the same weight, and they’re leaving the same things (everything else) on your shoulders. Which is not to say that there aren’t meaningful differences, it’s just that they’re the equivalent of changing the decor in your house, not rearranging the floorplan: What dice do you like using? What skill list do you prefer for a particular type of game? How much detail do you like in your skill resolution and/or combat? And so forth.

SYSTEM MATTERS

What I’m saying is that system matters. But when it comes to mainstream RPGs, this truth is obfuscated because their systems all matter in exactly the same way. And this is problematic because it has created a blindspot; and that blindspot is resulting in bad game design. It’s making RPGs less accessible to new players and more difficult for existing players.

I’ve asked you to ponder the hypothetical scenario of taking your favorite RPG and removing the combat system from it. Now let’s consider the example of a structure which actually HAS been ripped out of game… although you may not have noticed that it happened.

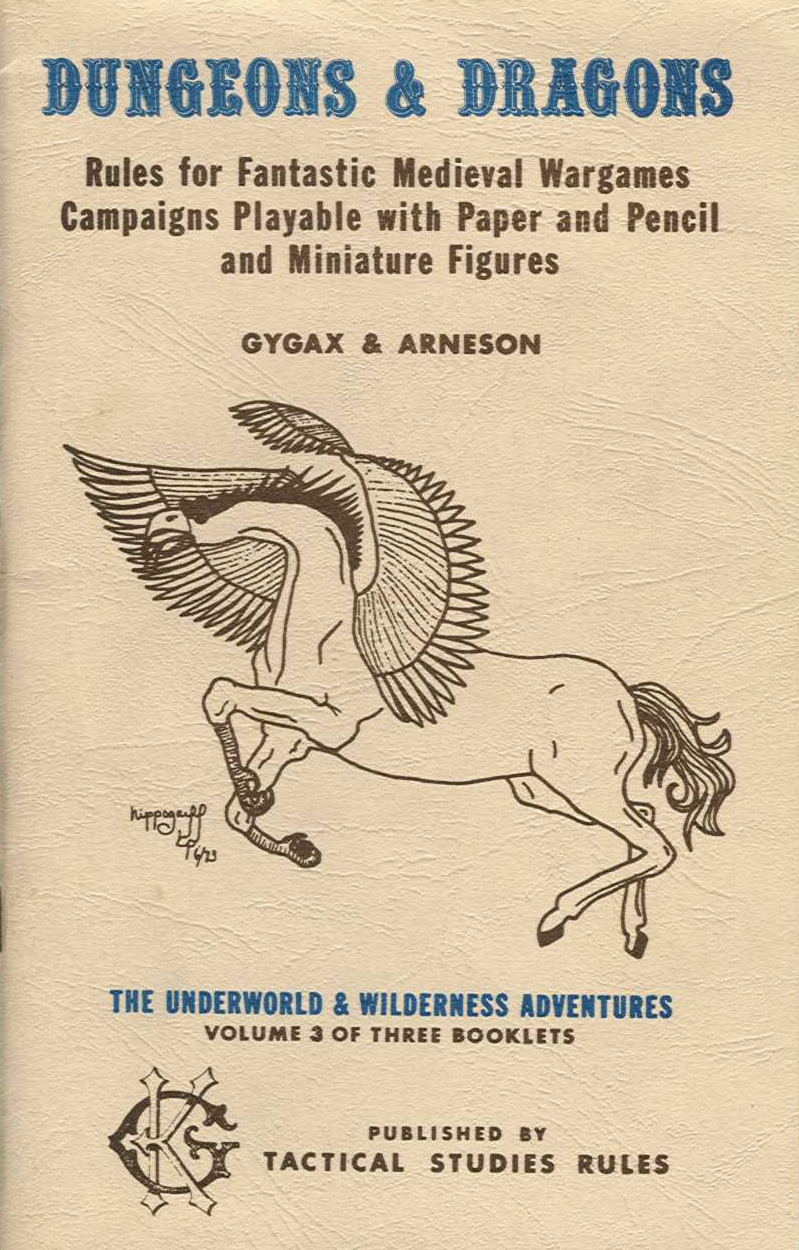

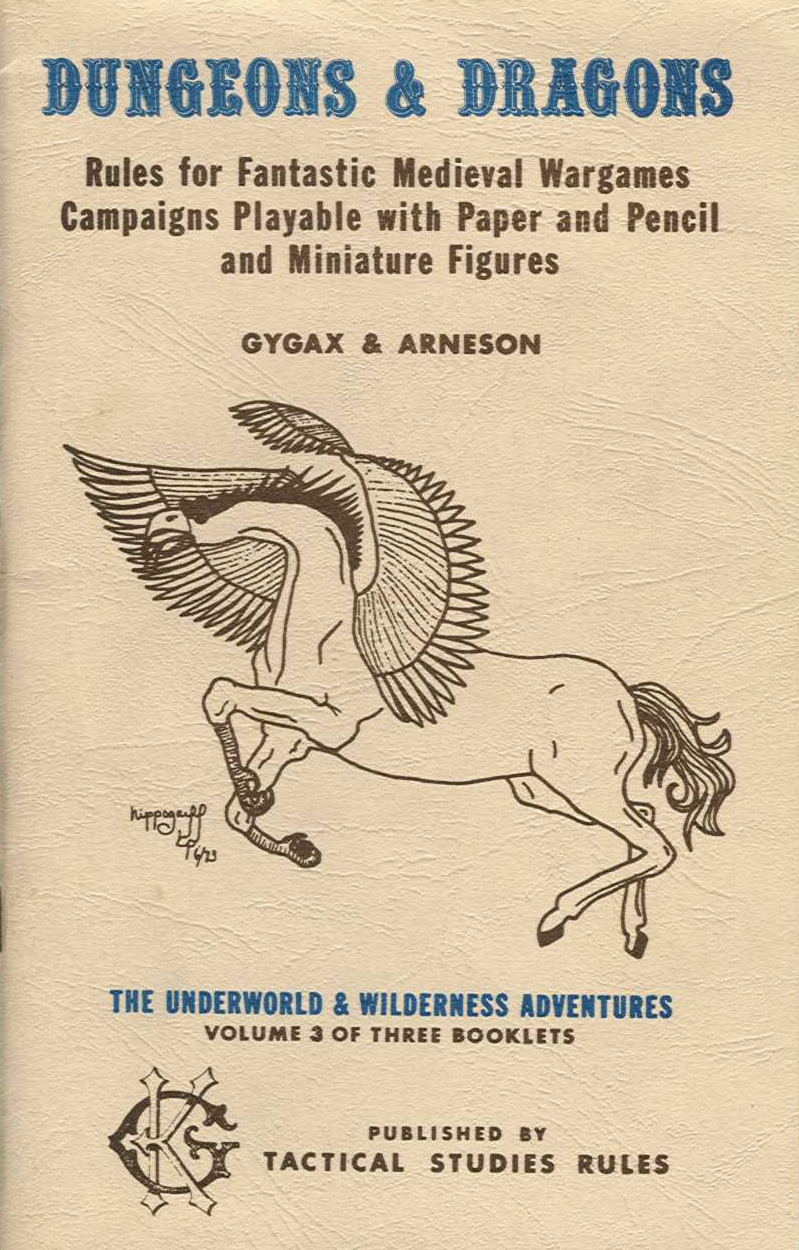

From page 8 to page 12 of The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures, Arneson & Gygax spelled out a very specific procedure for running dungeons in the original edition of Dungeons & Dragons. It boils down to:

1. You can move a distance based on your speed and encumbrance per turn.

1. You can move a distance based on your speed and encumbrance per turn.

2. Non-movement activities also take up a turn or some fraction of a turn. For example:

- ESPing takes 1/4 turn.

- Searching a 10′ section of wall takes 1 turn. (Secret passages found 2 in 6 by men, dwarves, or hobbits; 4 in 6 by elves.

3. 1 turn in 6 must be spent resting. If a flight/pursuit has taken place, you must rest for 2 turns.

4. Wandering Monsters: 1 in 6 chance each turn. (Tables provided.)

5. Monsters: When encountered, roll 2d6 to determine reaction (2-5 negative, 6-8 uncertain, 9-12 positive).

- Sighted: 2d4 x 10 feet.

- Surprise: 2 in 6 chance. 25% chance that character drops a held item. Sighted at 1d3 x 10 feet instead.

- Avoiding: If lead of 90 feet established, monster will stop pursuing. If PCs turn a corner, 2 in 6 chance they keep pursuing. If PCs go through secret door, 1 in 6 chance they keep pursuing. Burning oil deters many monsters from pursuing. Dropping edible items has a chance of distracting intelligent (10%), semi-intelligent (50%), or non-intelligent (90%) monsters so they stop pursuing. Dropping treasure also has a chance of distracting intelligent pursuers (90%), semi-intelligent (50%), or non-intelligent (10%) monsters.

6. Other activities:

- Doors must be forced open (2 in 6 chance; 1 in 6 for lighter characters). Up to three characters can force a door simultaneously, but forcing a door means you can’t immediately react to what’s on the other side. Doors automatically shut. You can wedge doors open with spikes, but there’s a 2 in 6 chance the wedge will slip while you’re gone.

- Traps are sprung 2 in 6.

- Listening at doors gives you a 1 in 6 (humans) or 2 in 6 (elves, dwarves, hobbits) of detecting sound. Undead do not make sound.

I’ve said this before, but if you’ve never actually run a classic megadungeon using this procedure — and I mean strictly observing this procedure — then I strongly encourage you to do so for a couple of sessions. I’m not saying you’ll necessarily love it (everyone has different tastes), but it’s a mind-opening experience that will teach you a lot about the importance of game structures and why system matters.

The other interesting thing here is that Arneson & Gygax pair this very specific procedure with very specific guidance on exactly what the DM is supposed to prep when creating a dungeon on pages 3 thru 8 of the same pamphlet. (These two things are conjoined: They can tell you exactly what to prep because they’re also telling you exactly how to use it.) Take these two things plus a combat system for dealing with hostile monster and, if you’re a first time GM, you can follow these instructions and run a successful game. It’s a simple, step-by-step guide.

“Now wait a minute,” you might be saying. “You said this procedure had been ripped out of D&D. What are you talking about? There’s still dungeon crawling in D&D!”

… but is there?

THE SLOW LOSS OF STRUCTURE

Many of the rules I describe above have passed down from one edition to the next and can still be found, in one form or another, in the game as it exists today. But if you actually sit down and look at the progression of Dungeon Master’s Guides, you’ll discover that starting with 2nd Edition the actual procedure began to wither away and eventually vanished entirely with 4th Edition.

The guidance on how to prep a dungeon has proven to have a little more endurance, but it, too, has atrophied. The 5th Edition core rulebooks, for just one example, don’t actually tell you how to key a dungeon map. (And although they have several example maps, none of them actually feature a key.)

One of the nifty things about a strong, robust scenario structure like dungeon crawling is that with a fairly mild amount of fiddling you can move it from one system to another. This is partly because most RPGs are built on the model of D&D, but it’s also because scenario structures in RPGs tend to be closely rooted to the fictional state of the game world.

This is, in fact, why you probably didn’t notice that 5th Edition D&D doesn’t actually have dungeon crawling in it any more: You’re familiar with the structure of dungeon crawling, and you unconsciously transferred it to the new edition the same way that you’ve most likely transferred it to other games lacking a dungeon crawling structure in the past. In fact, I’m willing to guess that removing dungeon crawling from 5th Edition was not, in fact, a conscious decision on the part of the designers: They learned how to run a dungeoncrawl decades ago and, like you, have been unconsciously transferring that structure from one game to another ever since.

Where this becomes a problem, however, are all the new players who don’t know how to run a dungeoncrawl.

Most people enter the hobby through D&D. And D&D used to reliably teach every new DM two very important procedures:

1. How to run a dungeon crawl

2. How to run combat

And using just those two procedures (easily genericizing the dungeon crawling procedure to handle any form of location-crawl), a GM can get a lot of mileage. In fact, I would argue that most of the RPG industry is built on just these two structures, and that most GMs really only know how to use these two structures plus railroading.

So what happens when D&D stops teaching new DMs how to run a dungeoncrawl?

It means that GMs are now reliant entirely on railroading and combat.

And that’s not good for the hobby.

THE BLINDSPOT

If you need another example of what this looks like in practice, check out The Lost Mine of Phandelver, the scenario that comes with the D&D 5th Edition Starter Set. It’s a fascinating look at how this really is a blindspot for the 5th Edition designers, because The Lost Mine of Phandelver includes a lot of GM advice.  They tell you that the GM needs to:

They tell you that the GM needs to:

- Referee

- Narrate

- Play the monsters

They give lots of solid, basic advice like:

- When in doubt, make it up

- It’s not a competition

- It’s a shared story

- Be consistent

- Make sure everyone is involved

- Be fair

- Pay attention

There’s a detailed guide on how to make rulings. They tell you how to set up an adventure hook.

Then the adventure starts and they tell you:

- This is boxed text, you should read it.

- Here is a list of specific things you should do; including getting a marching order so that you know where they’re positioned when the goblins ambush them.

- When the goblins ambush them, they give the DM a step-by-step guide for how combat should start and what they should be doing while running the combat.

- They lay out several specific ways that the PCs can track the goblins back to their lair, and walk the DM through resolving each of them.

And then you get to the goblins’ lair and… nothing.

I mean, they do an absolutely fantastic job presenting the dungeon:

- General Features

- What the Goblins Know (always love this)

- Keyed map

- And, of course, the key entries themselves describing each room

But the step-by-step instructions for how you’re actually supposed to use this material? It simply… stops. The designers clearly expect, almost certainly without actually consciously thinking about it, that how you run a dungeon is so obvious that even people who need to be explicitly told that they should read the boxed text out loud don’t need to be told how to run a dungeon.

And because they believe it’s obvious, they don’t include it in the game. And because they don’t include it in the game, new DMs don’t learn it. And, as a result, it stops being obvious.

(To be perfectly clear here: I’m not saying that you need the exact structure for dungeon crawling found in OD&D. That would be silly. But the core, fundamental structure of a location-crawl is not only an essential component for D&D; it’s really fundamental to virtually ALL roleplaying games.)

THE BLINDSPOT PARADOX

Paradoxically, this blindspot not only strips structure from RPGs by removing those structures; it also strips structure from RPGs by blindly forcing structures.

It is very common for a table of RPG players to have a sort of preconceived concept of what functions an RPG is supposed to be fulfilling, and when they encounter a new system they frequently just default back to the sort of “meta-RPG” they never really stop playing. This is encouraged by the fact that the RPG hobby is permeated by the same meme that rules are disposable, with statements like:

- “You should just fudge the results!”

- “Ignore the rules if you need to!”

A widespread culture of kitbashing, of course, is not inherently problematic. It’s a rich and important tradition in the RPG hobby. But it does get a little weird when people start radically houseruling a system before they’ve even played it… often to make it look just like every other RPG they’ve played. (For example, I had a discussion with a guy who said he didn’t enjoy playing Numenera: Before play he’d decided he didn’t like the point spend mechanic for resolving skill checks; didn’t like XP spends for effect; and didn’t like GM intrusions so he didn’t use any of those mechanics. He also radically revamped how the central Effort mechanic works in the game. Nothing inherently wrong with doing any of that, but he never actually played Numenera.)

As a game designer, I actually find it incredibly difficult to get meaningful playtest feedback from RPG players because, by and large, none of them are actually playing the game.

And these memes get even weirder when you encounter them in game designers themselves: People who are ostensibly designing robust rules for other people to use, but in whom the response to “just fudge around it” has become so ingrained that they do it while playtesting their own games instead of recognizing mechanical failures and structural shortcomings and figuring out how to fix them.

EXCEPTIONS TO THE BLINDSPOT

To circle all the way back around here: System Matters. But due to the longstanding blindspot when it comes to game structures and scenario structures in RPGs, we’ve stunted the growth of RPGs. Most of our RPGs are basically the same game, and they shouldn’t be. The RPG medium should be as rich and varied in the games it supports as, for example, the board game industry is. Instead, we have the equivalent of an industry where every board game plays just like Settlers of Catan.

Now there are exceptions to this blindspot when it comes to scenario structures. Partly influenced by storytelling games (which often feature very rigid scenario structures), we’ve been seeing an increasing number of RPGs beginning to incorporate at least partial scenario structures.

Blades in the Dark, for example, has a crew system that supports developing a criminal gang over time. Ars Magica does something similar for a covenant of wizards. Reign provides a generic cap system for managing player-run organizations in competition with other organizations.

Technoir features a plot-mapping scenario structure that’s tied into character creation and noir-driven mechanics.

For Infinity I designed the Psywar system to provide support for complex social challenges (con artistry, social investigation, etc.).

You can also, of course, visit some of the game structures I’ve explored here on the Alexandrian: Party Planning, Tactical Hacking, Urbancrawls. The ongoing Scenario Structure Challenge series will continue to explore these ideas.

Go to Game Structures

1. You can move a distance based on your speed and encumbrance per turn.

1. You can move a distance based on your speed and encumbrance per turn.