Vagabundork asks, “Why would the PCs accept these missions? Why would a satanist neuroscientist, a self-hatred writer, and a Colombian telenovela actress get involved in a scenario like this? (…) It usually falls to the, ‘we are a paranormal investigation agency’ which (…) removes all that makes cosmic horror awesome.”

There are a few ways to handle this, generally speaking.

First: Get the players on board during the character creation process.

It’s not solely your responsibility, as the Game Master, to explain why all these characters are hanging out together. As they’re creating the group, make sure the players figure out why these characters are operating together.

“We all have a job in the same organization” (i.e., the paranormal investigation agency) is an easy fits-all-scenarios answer to this, but it’s hardly the only one. What do they care about? What common goal do they all share? What secret do they all have in common?

Once you know what makes them a group, you can hang your scenario hooks off of it. This works even if their connection seems mundane and unrelated to whatever the scenario is. For example, let’s say they decide that they all work at the same comic book shop. Great, now you can threaten the store. Or have some strange person/creature come into the store. Or maybe the whole structure of the campaign becomes tracking down rare issues of comic books for resale, and the weird places, people, and estate sales they track down to obtain those issues also get them tangled up in whatever the scenario happens to be.

If they all share a dark secret, then a scenario hook just needs to threaten that secret in some way to pull them all in. Or they can all be blackmailed by the same mysterious patron.

Note: Just because the players are all collectively figuring out what binds their characters together, this doesn’t necessarily mean that the characters all know each other when the game begins! For example, they can all want to find the Ruby Eye of Drosnin or figure out the Truth About the Templars and be actively pursuing that without pursuing it together (at least not initially), which can also tie into…

Second: Use separate hooks.

If you design scenarios that are awesome situations instead plots, then you’ll discover that your scenarios aren’t generally limited to a single scenario hook: The cooler and more dynamic the situation, the more places there are to hang your hooks. Vagabundork’s question actually came in response to one such discussion (Scenario Hooks for Over the Edge), and you can also check out Juggling Scenario Hooks in a Sandbox for a different perspective on the same basic concept.

This also means that you don’t have to come up with a single explanation for why all of the PCs are involved in the current scenario. They can all be there for completely different reasons, quite possibly pursuing very different agendas.

It’s not unusual to have an initial scenario that works like this, but then the expectation is that, at the end of the scenario, all of these characters will decide that this was a jolly good time and they should all hang out doing similar stuff from now on. This can work very well in games that have a strong in-fiction conceit for small groups of freelancers coming together like this: D&D adventuring parties or Shadowrun teams, for example.

This is also, however, only the most generic version of this, and you can get a lot of mileage out of the same technique by making it specific. For example, during the first scenario all of the PCs get sprayed by a strange blue goo and now they share a common curse. Even if they don’t decide to all team up to figure it out together, they now all have a common goal… which means we’re back in scenario one and you can easily keep hooking them back into the same blue goo-related scenarios. If you can figure out a way to do this that ties into their specific character arcs and backgrounds, then you’ll get results that are even more specific and, as a result, powerful and meaningful.

This technique can also work well when combined with time skips: If the PCs are all pursuing different agendas, then it would be weird for those agendas to all coincidentally cross paths with each other every couple of days. But if you have a really cool scenario, wrap it up, and then deliberately skip a few months or years (or decades) until the next time these characters all happen to cross paths again, that can be a really cool conceit.

A specific variation of this technique is…

Third: Make them enemies.

Or, more specifically, set them in opposition to each other.

This is a technique I discuss in more detail in Technoir and PvP. The short version is that a good, situation-based scenario doesn’t actually need the PCs to be working together. It can often be even more interesting if they’re working in opposition to each other.

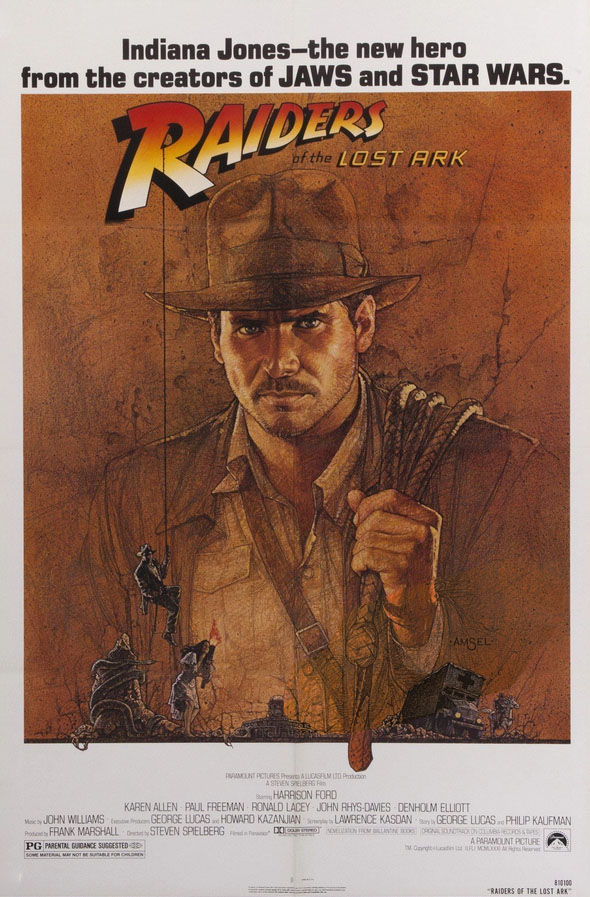

The simplest variation is to have different characters who both want the same thing and are in competition with each other for it. For example, Belloq and Indiana Jones from Raiders of the Lost Ark. The film not only contains two completely separate scenarios between these two antagonists, it reveals that they’ve been crossing paths like this over and over and over again for years. If you imagine them both as PCs, that sounds like an incredible campaign.

The simplest variation is to have different characters who both want the same thing and are in competition with each other for it. For example, Belloq and Indiana Jones from Raiders of the Lost Ark. The film not only contains two completely separate scenarios between these two antagonists, it reveals that they’ve been crossing paths like this over and over and over again for years. If you imagine them both as PCs, that sounds like an incredible campaign.

Another variation is to set things up so that one of the PCs is literally the objective of the other PC. Putting a bounty on the head of one of the PCs is a one-size-fits-all solution to this. The TV show The Fugitive, for example, uses this gimmick. If it was a campaign, the GM only needs to figure out how to hook Richard Kimble into each scenario… and then Lt. Philip Gerard will come following right behind.

This state of antagonism doesn’t have to be entered into with the expectation that it will last in perpetuity, however. When the PCs discover that their antagonism was all a big misunderstanding or, after being forced to work together, realizing that they actually make a really great team, this can collapse into Scenario Two above. (See, for example, basically the entire The Fast & the Furious franchise.)

When using this technique, however, you need to be prepared to actually lose PCs, either because they’re killed or because they just don’t want to work together. That can be OK. (Having one of the PCs leave only to return several sessions later as an antagonist not only for the original PC but for the new PC played by the antagonist’s player can be really cool.)

Fourth: Give them a patron.

When all else fails, patrons make scenario hooks easy: They tell you what your next gig is and then you do it.

The other nice thing about a patron is that you don’t need to figure out why all the PCs know each other or want to work with each other: You just need to figure out (a) why the patron would want to hire each of them individually and (b) why each of them would be willing to take the gig.

The fact that PCs tend to be hyper-competent usually provides the generic answer to the former. Money is a one-size-fits-all answer for the latter.

Nothing wrong with these generic answers, of course. Shadowrun basically builds a whole game around those answers and it does so very successfully.

But, once again, making things more specific instead of generic is generally going to give you better results. Fortunately, it’s generally easier to do this specifically because you don’t need to have the same answers for each PC.

You can also, once again, get the players onboard with this process during character creation. For example, the first time that I ran Eternal Lies, I simply asked the players to make sure that their character backgrounds explained why someone would be interested in hiring them to look into paranormal weirdness. The answers they came up with were all over the map (Chicago cop who got a string of weird cases; girl detective and her brother working amateur paranormal cases in London; combat pilot; author of Fortean nonfiction masquerading as ‘weird fiction’), but also chock full of awesomeness that made it easy to explain why their patron might want to pull them together to investigate her father’s mysterious legacy.

The second time I ran Eternal Lies, however, some of the players ended up with concepts that weren’t as clear-cut in terms of why a patron would seek them out. But we were still able to work together to figure out more personal connections justifying the hire. (For example, one of the characters had been previously involved with a friend of the patron. Another had briefly encountered her father and was, as a result, mentioned in the mysterious notes the group was being hired to investigate.)

Alternatively, maybe the PCs all DO have the same reason for working for the patron: Making that infernal pact so that you could all open a comic book store together sure seemed like a good idea at the time, but…

Another good variation here is to make one of the PCs the patron. See Ocean’s Eleven, for example. This, once again, narrows the focus of the scenario hook down to the desires of a single character, while simplifying everyone else’s involvement down to the question of why someone would want them on the team (which will generally boil down to expertise).

“You just need to figure out (a) why the patron would want to hire each of them individually and (b) why each of them would be willing to take the gig.

…

But, once again, making things more specific instead of generic is generally going to give you better results. Fortunately, it’s generally easier to do this specifically because you don’t need to have the same answers for each PC.”

This made me think of the Doctor Who episode “Time Heist”, in which the Doctor and his companion team up with a shapeshifter and a cyborg hacker to break into the most secure vault in the galaxy. Each of them is on the team for a specific reason, and each of them has their own reason for agreeing to the heist.

The twist is that the plan required them to submit to a short-term memory wipe, so they don’t *remember* what those reasons were, *or* who their patron is, *or* why they’re breaking into the vault, and they have to figure it out as they go.

One of the thing I like in the cypher system is that each character focus has suggestions for links between PCs. For instance if you pick « crafts illusions », it is suggested that for some reason one of the others PCs sees right through your illusions.

It really nudges players into thinking about how they’ve known each other before session one, or at least establish something special between them to at least have just a basis to role play their interactions.

Something cool that you can do with Option #3: Imagine there’s this McGuffin that a bunch of different factions (or at the very least two opposed factions) all want, hidden inside some kind of dungeon or behind some kind of defenses. The PCs are working for the different factions, but they all need to work together to get the McGuffin, and they all know that. So each PC has to walk this delicate line as they descend into the dungeon: You want the other PCs to expend resources and take injuries, because that will weaken them for the final battle over the McGuffin, and you would be pleased if the other PCs die so you don’t have to fight them, but if you betray another PC too obviously they might all gang up on you for breaking the truce, and if you let another PC die too early it’ll become harder for you to get past the rest of the defenses. That makes for a really cool dynamic.