There’s been a recent memetic trend of attempting to defend the idea of railroading your PCs by, first, claiming that a bunch of stuff that isn’t railroading is a “railroad” and then using that claim to conclude that railroading isn’t bad and we should all just stop worrying about it.

It’s as if I said, “Racism isn’t all bad. After all, apple pies are totally racist. But they taste delicious, right?” It sounds perfectly reasonable until you notice that the bit about apple pies being racist is bullshit.

One thing to keep in mind is that the metaphorical use of the verb “railroad” is not a piece of terminology unique to RPGs. It’s an English word dating to 1884 that means, “To force someone into doing something by rushing or coercing them.” Whenever you see someone trying to defend railroading by claiming that it includes a bunch of techniques that don’t include forcing the players to do something they don’t want to do, they’re abusing the terminology. The term “railroading” in this context has an inherently negative connotation, and it’s simply not useful to attempt to redefine the English language so that you can use the term “railroad” to describe some completely different technique that isn’t railroading.

What would be useful, on the other hand, is a new term that we could use to describe the body of techniques which limit player choice. We’re going to call them chokers. (Because they create chokepoints in your scenario design.)

Limiting player choice, you’ll note, is distinctly different from negating their choices. While chokers can certainly be abused in order to constrain choice to the point where the GM is enforcing their preconceived outcome by default, imposing creative restraint upon a given situation creates interest and variety.

For those particularly paranoid about limiting the choices available to a PC, it may be useful to note that these chokers will also appear organically and spontaneously through play. The natural world, after all, often surrounds us by barriers. (For example, I am currently sitting in my office. The only way I can easily leave my office is through the door. I could also climb out the window. I might be able to hack my way through the wall, but that’s unlikely. The nature of the room has limited my choices.)

Being aware of these chokers will not only allow you to take advantage of their strengths, but also avoid their perils. The Three Clue Rule is an example of that: A breadcrumb-style mystery scenario is formed from a series of chokers, with each clue providing a very narrow and very specific path that leads to the next clue. The Three Clue Rule simply adds more clues, removing the choker and allowing the scenario to proceed smoothly.

THE ROAD

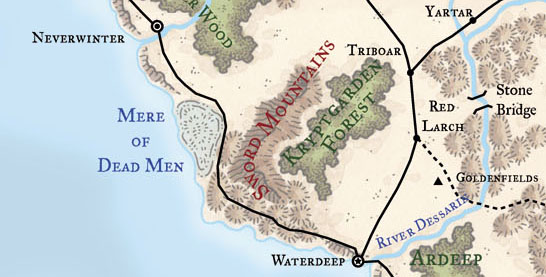

Let’s say that the PCs want to travel from Waterdeep to Neverwinter. Why they want to do this is largely irrelevant: Maybe they just learned that the man who killed their father has fled to Neverwinter. Or they’re traders who’ve heard that their Tethyrian textiles will fetch a good price there. Or maybe they just randomly decided to go there at the end of the last session.

So they look at the map and they say, “Hey. Let’s take the road.”

The road is a natural choker, narrowing their experiences to a sequence of literally linear events. For example, you could look at this journey from Waterdeep to Neverwinter and simply prepare it as:

- As they enter the Sword Mountains, they’re attacked by the Blood Shield Bandits.

- Black water kappa will emerge from the Mere of Dead Men as they pass it.

- North of the Mere of Dead Men they’ll encounter Benedict, an itinerant merchant with a beautiful daughter. The axle of their wagon has broken.

Insofar as the road is the natural choice for traveling from Waterdeep to Neverwinter, the choice of going to Neverwinter triggers this specific sequence of events.

Of course, one can loosen the choker if the PCs can choose from a variety of routes. For example, instead of taking the road from Waterdeep to Neverwinter, the PCs could book travel on a ship. (Of course, the journey by ship merely presents a different set of linear experiences.)

It should be noted, however, that the mere existence of multiple routes is often a false choice unless the choice between routes includes an incomparable difference. For example, if the PCs are concerned with speed and the only difference between the journey by sea and the journey by road is the amount of time they take, then there is no real choice: There’s only a calculation of which route will get them there faster. (See The Importance of Choice for a complete discussion of this.)

What I think is interesting about literal roads, however, is that they usually contain an incomparable choice by their very nature. For example, imagine that the PCs are going from Waterdeep to Triboar. There’s only one road, so that’s the way they have to go, right? Except, of course, they could also choose to journey cross-country. The cross-country journey would be slower, but it would also mean avoiding whatever troubles there might be on the road. (The choice between speed and avoiding the events on the road is the incomparable.)

Of course, not all roads are literal roads. Another metaphor for this sort of choker is a bullet in flight: The PCs load themselves into a gun and then pull the trigger. The choice of pulling the trigger is theirs, but once they have done so their flight will logically and naturally take them through a sequence of experiences. As long as they choose to remain upon the bullet, the bullet will continue to fly. You can either take this opportunity to show them some awesome stuff midflight or you can challenge them in order to make the decision to stay on the bullet a meaningful one.

A third way of understanding this choker is “looking out the train window”. Once they’ve made the decision to get on the train, it’s not necessarily impossible to get off before the next stop, but they’d have to put considerable effort into doing so. The metaphor of the train, however, also highlights the ability to create a rich scenario full of complex choices on the train: There may be a linear sequence of events rushing past the windows in the background, but that doesn’t need to be true of the immediate experiences of the PCs. (Maiden Voyage, a D20 adventure by Mike Mearls, is an excellent example of this type of scenario.)

Where you can get yourself into trouble is assuming that the PCs will take a road when they have no need to do so. (Or, worse yet, strong reasons for not taking the road.) For example, the Horror on the Orient Express campaign for Call of Cthulhu ironically makes it a bad idea for the PCs to take the Orient Express. (And then doubles down later in the campaign by, in fact, making it quite difficult for the PCs to stay on the train.)

MECHANICAL GATES

A mechanical gate exists whenever the PCs need to succeed on an action check in order to do a thing or go to a place or otherwise have a particular experience.

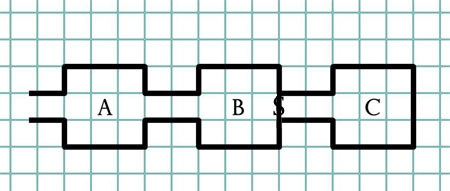

The simplest example of this is a secret door in a dungeon:

If the PCs fail to detect the secret door in Area B, then they will never discover Area C.

A mechanical gate like this is only a problem, of course, if Area C is of vital importance. For example, if Area C is the only place you can find the cure for the Princess’ disease. If the content in Area C is non-essential, on the other hand, then it simply serves as an optional reward for PCs who successfully leap the mechanical hurdle.

A common example of the mechanical gate is the breadcrumb trail approach to mystery scenario design: Every clue is necessary to reach the next section of the scenario, and thus every skill check to find a clue is a mechanical gate which must be passed through in order for the scenario to succeed. (This is the broken scenario structure which the Three Clue Rule seeks to fix. It’s like adding additional routes by which the secret chamber in the dungeon can be found.)